Critiquing Cultural Relativism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relativism of Blame and Williams' Relativism of Distance

ABSTRACT: Bernard Williams is a sceptic about the objectivity of moral value, embracing instead a certain qualified moral relativism—the ‘relativism of distance’. His attitude to blame too is in part sceptical (he thought it often involved a certain ‘fantasy’). I will argue that the relativism of distance is unconvincing, even incoherent; but also that it is detachable from the rest of Williams’ moral philosophy. I will then go on to propose an entirely localized thesis I call the relativism of blame, which says that when an agent’s moral shortcomings by our lights are a matter of their living according to the moral thinking of their day, judgements of blame are out of order. Finally, I will propose a form of moral judgement we may sometimes quite properly direct towards historically distant agents when blame is inappropriate—moral-epistemic disappointment. Together these two proposals may help release us from the grip of the idea that moral appraisal always involves the potential applicability of blame, and so from a key source of the relativist idea that moral appraisal is inappropriate over distance. The Relativism of Blame and Williams’ Relativism of Distance Must I think of myself as visiting in judgement all the reaches of history? Of course, one can imagine oneself as Kant at the court of King Arthur, disapproving of its injustices, but exactly what grip does this get on one’s ethical or political thought?1 Bernard Williams famously argued for a distinctive brand of moral relativism, which he regarded as capturing the truth in relativism, and which he called the relativism of distance. -

On the Coherence of Sartre's Defense of Existentialism Against The

Untitled 7/12/05 3:41 PM On the Coherence of Sartre’s Defense of Existentialism Against the Essentialist Charge of Ethical Relativism in His “Existentialism and Humanism” Brad Cherry I.Introduction Although its slim volume may suggest otherwise, Jean-Paul Sartre’s “Existentialism and Humanism” treats a wealth of existentialist themes. Indeed, within its pages, Sartre characterizes many of the hallmarks of existentialist thought, including subjectivity, freedom, responsibility, anguish, forlornness, despair, and so on. Perhaps most importantly, however, Sartre’s “Existentialism and Humanism” occasions a defense of existentialism against its most frequently dealt criticisms, particularly the essentialist charge that existentialism necessarily gives rise to ethical relativism. And while this defense may seem convincing at first, in many places, it also seems to abandon, for the sake of its project, the fundamental commitments of existentialism, at least as Sartre understands them. Thus, in this essay, I critically examine the coherence of Sartre’s defense of existentialism against the essentialist charge of ethical relativism. To the extent that that defense relies largely upon his espousal of an existentialist ethics, I examine, in particular, whether that ethics coheres with the fundamental commitments of existentialism as he understands them. Following this examination, I conclude that (a) the fundamental commitments of existentialism preclude Sartre from coherently positing objectively valid normative ethical statements, that (b) because he nonetheless posits such statements in his espousal of an existentialist ethics, his defense of existentialism against the essentialist charge of ethical relativism breaks down, and finally, that (c) although this incoherence presents a substantial problem for Sartre, one may still defend his attempt to espouse an existentialist ethics. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

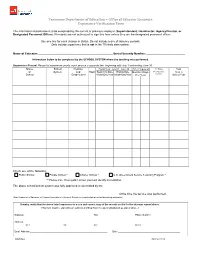

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Islamization of Anthropological Knowledge

The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences Vol. 6. No. 1, 1989 143 Review Article Islamization of Anthropological Knowledge A. R. Momin The expansion of Western coloniaHsrn during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries brought in its wake the economic and political domination and exploitation of the Third World countries. Western colonialism and ethnocentrism went hand in hand. The colonial ideology was rationalized and justified in terms of the white man's burden; it was believed that the White races of Europe had the moral duty to carry the torch of civilization which was equated with Christianity and Western culture-to the dark comers of Asia and Africa. The ideology of Victorian Europe accorded the full status of humanity only to European Christians; the "other" people were condemned, as Edmund Leach has bluntly put it, as "sub-human animals, monsters, degenerate men, damned souls, or the products of a separate creation" (Leach, 1982). One of the most damaging consequences of colonialism relates to a massive undermining of the self-confidence of the colonized peoples. Their cultural values and institutions were ridiculed and harshly criticized. Worse still, the Western pattern of education introduced by colonial governments produced a breed of Westernized native elite, who held their own cultural heritage in contempt and who consciously identified themselves with the culture of their colonial masters. During the nineteenth century Orientalism emerged as an intellectual ally of Western colonialism. As Edward Said has cogently demonstrated, Oriental ism was a product of certain political and ideological forces operating in Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and that it was inextricably bound up with Western ethnocentrism, racism, and imperialism (Said, 1978). -

Franz Boas's Legacy of “Useful Knowledge”: the APS Archives And

Franz Boas’s Legacy of “Useful Knowledge”: The APS Archives and the Future of Americanist Anthropology1 REGNA DARNELL Distinguished University Professor of Anthropology University of Western Ontario t is a pleasure and privilege, though also somewhat intimidating, to address the assembled membership of the American Philosophical ISociety. Like the august founders under whose portraits we assemble, Members come to hear their peers share the results of their inquiries across the full range of the sciences and arenas of public affairs to which they have contributed “useful knowledge.” Prior to the profes- sionalization of science in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the boundaries between disciplines were far less significant than they are today. Those who were not experts in particular topics could rest assured that their peers were capable of assessing both the state of knowledge in each other’s fields and the implications for society. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington were all polymaths, covering what we now separate into several kinds of science, humanities, and social science in ways that crosscut one another and illustrate the permeability of disciplinary boundaries. The study of the American Indian is a piece of that multidisciplinary heri- tage that constituted the APS and continues to characterize its public persona. The Founding Members of the Society all had direct and seminal experience with the Indians and with the conflict between their traditional ways of life and the infringing world of settler colonialism. On the one hand, they felt justified in exploiting Native resources, as surveyors, treaty negotiators, and land speculators. On the other hand, the Indians represented the uniqueness of the Americas, of the New World that defined itself apart from the decadence of old Europe. -

History of the Human Sciences

History of the Human Sciences http://hhs.sagepub.com/ Herder: culture, anthropology and the Enlightenment David Denby History of the Human Sciences 2005 18: 55 DOI: 10.1177/0952695105051126 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hhs.sagepub.com/content/18/1/55 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for History of the Human Sciences can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hhs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hhs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://hhs.sagepub.com/content/18/1/55.refs.html Downloaded from hhs.sagepub.com at Zabol University on November 23, 2010 03HHS18-1 Denby (ds) 8/3/05 8:47 am Page 55 HISTORY OF THE HUMAN SCIENCES Vol. 18 No. 1 © 2005 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) pp. 55–76 [18:1;55–76; DOI: 10.1177/0952695105051126] Herder: culture, anthropology and the Enlightenment DAVID DENBY ABSTRACT The anthropological sensibility has often been seen as growing out of opposition to Enlightenment universalism. Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) is often cited as an ancestor of modern cultural relativism, in which cultures exist in the plural. This article argues that Herder’s anthropology, and anthropology generally, are more closely related to Enlightenment thought than is generally considered. Herder certainly attacks Enlightenment abstraction, the arrogance of its Eurocentric historical teleology, and argues the case for a proto-hermeneutical approach which emphasizes embeddedness, horizon, the usefulness of prejudice. His suspicion of the ideology of progress and of associated theories of stadial development leads to a critique of cosmopolitanism and, particularly, of colonialism. -

Society: a Key Concept in Anthropology - Christian Giordano and Andrea Boscoboinik

ETHNOLOGY, ETHNOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY - Society: A Key Concept In Anthropology - Christian Giordano and Andrea Boscoboinik SOCIETY: A KEY CONCEPT IN ANTHROPOLOGY Christian Giordano and Andrea Boscoboinik University of Fribourg, Department of Social Sciences, Pérolles 90, 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland. Keywords: Society, Culture, Evolutionism, Functionalism, Structuralism, Post- Structuralism, Dynamic Anthropology, Diffusionism, Relativism, Interpretive Anthropology, Postmodern Anthropology Contents 1. Introduction: semantic ambiguities of the concept of anthropology 2. Pioneers of Social Anthropology: Evolutionism and Society 3. The Idea of Society in British Anthropology: Functionalism 4. The French School: Structuralism 5. From Structuralism to Post-Structuralism and Their Influence on Agency Theory 6. Against Stability: Dynamic Anthropology 7. Diffusionism, Historicism and Relativism in Franz Boas: Culture as the Expression of Society in American Anthropology 8. Beyond seemingly objective facts: the interpretive anthropology of Clifford Geertz 9. Postmodern Anthropology: The Advent of Methodological Individualism and the Omission of Society. 10. Conclusion. Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketches Summary In this chapter, we present the major anthropological currents that directly or indirectly made use of the notion of society in their theoretical reflections and analyses of empirical data. Having first clarified the polysemic nature of the term anthropology, we analyze the theoretical framework of early anthropologists who drew upon the evolutionist theories stemming from natural science. We then analyze British functionalism,UNESCO-EOLSS whose theoretical basis chiefly consists in a criticism of evolutionism, which was regarded as too speculative. Functionalism is characterized by its interest in institutions that, through their functions, generate cohesion in societies deemed primitive. TypicalSAMPLE of British functionalism is CHAPTERSthe empirical orientation of research put forward by Bronislaw Malinowski. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

NPTEL Moocs Multiple Choice Questions Assignment – Week II

NPTEL MOOCs Multiple Choice Questions Assignment – Week II Answer the following multiple choice questions (1 marks each) 15x1 1. Which of the following statement is correct? a) Culture is a way of life which is created by human beings and necessarily includes dimensions of both material or objective and symbolic or subjective b) Culture is a way of life shared by certain groups of people within certain value system and norms and does not necessarily include material or objective dimension c) Culture is a way of defining human body through its physical features d) None of the above 2. The study of the relationships and interactions among humans, their biology, their cultures, and their physical environments is known as? a) Ecology b) Human ecology c) Deep ecology d) All of the above 3. The study of the biological aspect of the human-environment relationship is known as? a) Human biological ecology b) Cultural ecology c) Human ecology d) All of the above 4. Who among the following developed the concept of cultural ecology? a) Julian Steward b) Herbert Spencer c) Charles Darwin d) Roy Rappaport 5. Which of the following is not part of economic system? a) Production (produce the things they need) b) Exchange (exchange things with each other and people of other societies c) Consumption (consume things) d) Distribution (distribute things) 6. In order to survive human beings collectively produce the means of subsistence and enhance their social being with the use of available technology is known as a) Means of production b) Reproduction c) Mode of production d) All of the above 7. -

Theory Reflections: Linguistic Determinism/Relativism

Theory Reflections: Linguistic Determinism/Relativism The Theory The theory of linguistic determinism and relativity presents a two-sided phenomenon: Does the specific language (and culture) we are exposed to in childhood determine, in fact, how we perceive the world, how we think, and how we express ourselves? If this is so, then, it must also be the case that each language (and the culture it represents) necessarily provides its speakers with a specific and differing view of that same world, a different way of thinking, and a different way of expressing. This notion is related to a parallel issue that has existed throughout the centuries—are there also universal absolutes that transcend all linguistic (and cultural) particulars? Recent research suggests there may be elements of both. Linguistic determinism came to the attention of linguists and anthropologists during the 1930s, prompted by the work of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Using prevailing linguistic approaches of his time, Whorf, who studied indigenous languages, found surprising contrasts with European tongues in terms of how they reflected and spoke about reality (e.g., how they segment the time continuum, construct lexical hierarchies and, in short, encode a different view of the world, or Weltanschauung). The Whorf-Sapir hypothesis, as it came to be known (Sapir was his teacher), gained increasing attention and prompted the notion of language determinism/relativity. In other words, the language we are born to has a direct effect upon how we conceptualize, think, interact, and express—a direct relationship between human language and human thinking This notion has remained at the center of a debate for more than half a century.