HIGHGATE NEW TOWN PHASE 1, CAMDEN Community-Led Conservation Guidance for Inclusion in the Dartmouth Park Conservation Area and Application for Grade II* Listing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C02648 A3L Alan Wito Dartmouth Park CA

W E us S mp A T a RC H y C ing HW I wa ild A L h u Y 5 E L E rc ll B RO 5 l LAC 6 P S e A e AD P A u Th enw CR R b rk 3 S le Sl 3 1 K ta C M 8 H A 1 2 I W H 7 G ar RS 59.0m d Bd E al H y 7 it AV El sp G H 95.4m Highgate Cemetery Ho ) g A 8 Whittington Hospital Sub Sta on in 9 gt W T 1 in 's F 84.9m 0 tt y E 8 i r 9 1 I 2 h a S Diving Platform T M W t H 9 Z (Highgate Wing) (S EW R IL M 8 O 0 L S Y ER 3 W P Tank 5 Y O A A 7 FB FL R 8 W K 1 6 E 1 S 2 E 1 2 1 PH 1 N 3 St James Villa 1 U A t O L o H 4 4 L A N 2 2 8 L O 2 99.3m r T O c Fitzroy T h Archway R w E 5 1 a M 3 y 9 Methodist Lodge C l o 9 3 s Central Shelter 1 e 8 1 Playground T Hall 0 7 C 21 5 B 84.8m to to 59.3m 184 1 T 81.5m E a n V Archway k 2 Chy O 4 183 0 R 7 to 4 Tavern 15 2 G o E t Surgery N 1 I U (PH) 1 in Apex N B 57.4m ra E C O 6 V 7 15 e D 3 A Lodge to ns s n 6 R 0 3 io en A 2 s 7 2 1 an rd 8 t 8 L a t r M o Mortuary ta ge t G 9 S A a 9 Lod lo 7 b y Lu u D l o 4 oll S G H t H l 3 22 E A a 5 1 to M ll 89 71.9m Ban B tre k u en il ily C D d 3 5 i am 8 Chy n 5 F 7 UE 91.5m to N A g 3 7 5 E 5 V s TT A 4 O B 9 O SH E o t 4 3 K AK o PCs 5 r O R 6 FB 5 o R 81.6m 8 t 8 A 4 o 5 7 o C El Sub Sta P 28 t 7 L o D IL n L H s 3 78.6m S t T 3 B C e , A S T c A a G E 27 Pl N PCs o r e y L t a 1 W c r D 1 t t N s e o R 1 a 3 1 0 u R A 5 r 7 7 FB 1 o t o s I o t b O i D 4 1 l 0 1 H 6 8 1 y L G 2 1 FB D n A C r E 2 y ch C w 5 s k l ay ion o l R S s 3 a C n n 4 m a 5 56.0m t T T M o o e a w s 3 g 7 W e R d 6 r Lo t A H ly y E 2 l o & Govt 83.9m H le E 1 2 s M 6 m L t 2 T 3. -

Download Our Student Guide for Over-18S

St Giles International London Highgate, 51 Shepherds Hill, Highgate, London N6 5QP Tel. +44 (0) 2083400828 E: [email protected] ST GILES GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AGED 18 LONDON IGHGATE AND OVER H Contents Part 1: St Giles London Highgate ......................................................................................................... 3 General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 On your first day… ............................................................................................................................... 3 Timetable of Lessons ............................................................................................................................ 4 The London Highgate Team ................................................................................................................. 5 Map of the College ............................................................................................................................... 6 Courses and Tests ................................................................................................................................. 8 Self-Access ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Rules and Expectations ...................................................................................................................... 10 College Facilities ............................................................................................................................... -

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet Barnet Underhill Hail & Ride section Great North Road Dollis Valley Way Barnet Odeon New Barnet Great North Road New Barnet Dinsdale Gardens East Barnet Sainsburys Longmore Avenue Route finder Great North Road Lyonsdown Road Whetstone High Road Whetstone Day buses *ULIÀQ for Totteridge & Whetstone Bus route Towards Bus stops Totteridge & Whetstone North Finchley High Road Totteridge Lane Hail & Ride section 82 North Finchley c d TOTTERIDGE Longland Drive 82 Woodside Park 460 Victoria a l Northiam N13 Woodside i j k Sussex Ring North Finchley 143 Archway Tally Ho Corner West Finchley Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Woodberry Grove Ballards Lane 326 Barnet i j k Nether Street Granville Road NORTH FINCHLEY Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Essex Park Finchley Central Ballards Lane North Finchley c d Regents Park Road Long Lane 460 The yellow tinted area includes every Dollis Park bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Regents Park Road Long Lane Willesden a l miles from Finchley South. Main stops Ballards Lane Hendon Lane Long Lane are shown in the white area outside. Vines Avenue Night buses Squires Lane HE ND Long Lane ON A Bus route Towards Bus stops VE GR k SP ST. MARY’S A EN VENUE A C V Hail & Ride section E E j L R HILL l C Avenue D L Manor View Aldwych a l R N13 CYPRUS AVENUE H House T e E R N f O Grounds East Finchley East End Road A W S m L E c d B A East End Road Cemetery Trinity Avenue North Finchley N I ` ST B E O d NT D R D O WINDSOR -

Abbey Road Belsize Road (Part Of) Cochrane Mews Aberdare Gardens

Abbey Road Belsize Road (Part Of) Cochrane Mews Aberdare Gardens Belsize Square Cochrane Street Acacia Gardens Berkley Grove Coity Road Acacia Place Beswick Mews Collard Place Acacia Road Birchwood Drive College Crescent Acol Road Blackburn Road Compayne Gardens Adamson Road Blenheim Road Connaught Mews Adelaide Road Boscastle Road Constatine Road Admiral's Walk Boundary Road (Part Of) Conybeare Agincourt Road Bracknell Gardens Copperbeech Close Ainger Road Bracknell Gate Courthope Road Ainsworth Way Bracknell Way Coutts Crescent Akenside Road Branch Hill Craddock Street Albany Street (Part Of) Briary Close Crediton Hill Albert Street Bridgeman Street Cressfield Close Albert Terrace Broadhurst Close Cressy Road Albert Terrace Mews Broadhurst Gradens Croftdown Road (Part Of) Alexandra Place Brocas Close Crogsland Road Alexandra Road Brookfield Park Crossfield Road Allcroft Road (Part Of) Broxwood Way Crown Close Allitsen Road Buckland Crescent Culworth Street Alvanley Gardens Burrard Road Cumberland Terrace Antrim Road Byron Mews Cumberland Terrace Mews Arkwright Road Calvert Street Dalby Street Arlington Road Camden High Street Dale Road Ashdown Crescent Camden Lock Place Daleham Gardens Aspern Grove Canfield Gardens Daleham Mews Athlone Street (Part Of) Canfield Place Dartmouth Park Road (Part Of) Auden Place Cannon Lane Delancey Street Avenue Close Cannon Place Denning Road Avenue Road Canon Hill Dobson Close Back Lane Carlingford Road Dorman Way Baptist Gardens Carlow Street Doulton Mews Barrington Close Carlton Hill (Part Of) Downshire -

Fitzpatrick Building, 188-194 York Way in the London Borough of Islington Planning Application No

planning report D&P/3804/01 1 September 2016 Fitzpatrick Building, 188-194 York Way in the London Borough of Islington planning application no. P2016/1999/FUL Strategic planning application stage 1 referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008. The proposal Demolition of existing office building and redevelopment to provide ground floor plus part 5/part 15 storey office building, including basement, ancillary ground floor cafe, 6th floor level terrace podium and roof plant room, cycle parking, plant/storage, landscaping and all other necessary works associated with the development. The applicant The applicant is Deepdale Investment Holdings, and the architect is Tibbalds Planning and Urban Design. Strategic issues summary: Land use: redevelopment of site for increased employment floorspace, and the proposed provision of affordable workspace, is supported. (paras. 14-20) Design: Height and architectural approach supported. (paras 21-24). Climate change: Shortfall in carbon reduction target should be met off-site (paras 26-34). Transport: improvements to public realm and cycle parking should be considered; contributions to bus stop and cycle hire required; conditions and section 106 obligations required (paras 37-45). Recommendation That Islington Council be advised that whilst the application is generally acceptable in strategic planning terms it does not fully comply with the London Plan for the reasons set out in paragraph 50 of this report. Possible remedies are set out in that paragraph to ensure full compliance with the London Plan. page 1 Context 1 On 4 July 2016 the Mayor of London received documents from Hounslow Council notifying him of a planning application of potential strategic importance to develop the above site for the above uses. -

Planning Process

PLANNING PROCESS There are a multitude of things to consider before starting works to your home. One of the first steps is to be clear of what are the benefits of the proposed changes to your household, and secondly, if these would require planning permission, or not. In order to estalish if planning permission is required, it is impornat you gain some awareness of the planning process by exploring what are the Council’s policies and guidance relevant for your project. This guidance aims to built up your awarness so you know what are the next steps in achieving your desired home improvement. USER JOURNEY 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Awareness & Pre- Engagement Submission Complete Review, pay Follow-up Decision Exploration application submission and submit advice Access Council website, Camden Local Plan 2017, Camden Planing Guidance If you are If you have not Access Complete Review the Now your If your application got (CPG), Conservation Area unclear done it already, a digital application form application application granted consent you need Appraisals, Neighbourhood what design before you platform such and upload all information, is with the to check if any conditions Plans. approach submit your as planning the information included. Pay Council. An or section 106 obligations would suit your application, portal, iapply, and drawings the required Officer will have to be discharged Use search engines building, you might be good etc. sign in/ relevant to your fee and press notify you about before you start work. (Google, Bing Maps) to should consider to discuss create an proposal on the submit. -

Maria Grey Training College List of Students 1879

Maria Grey Training College - Student List Name Other info Any other found in MGC Entry Year Graduation Address info Magazine Issue Page [From The Maria Grey Training College, List of Students 1879- 1911 ] 1879-80 26, The Avenue, MGC Magazine, Nov Adams (Mrs Corrie Grant) 1879-80 Bedford Park 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Barnett, J.M 1879-80 Deceased 1911 Deceased March, 1884 5 1) Mathematical Mistress, Newton Abbot High 1) November MGC Magazine, Nov School 2) Eversley, Hartley 1884 2) March Davey, E.A (Mrs Vine) 1879-80 Devonshire 1911 Road, Exmouth 1886 1) 23 2) 8 Wedhampton, MGC Magazine, Nov Ellis, E.H (Mrs Cox) 1879-80 Devizes 1911 Mildure, Victoria, MGC Magazine, Nov Gray, S.L (Mrs Beverley) 1879-80 Australia 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Jackson, E.A 1879-80 The Elms, Hendon 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Mitchell 1879-80 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Rowney, F.H (Mrs Jennings) 1879-80 1911 Crowhurst, Parkstone, MGC Magazine, Nov Scott, E 1879-80 Dorsetshire 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Stevens, M 1879-80 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Tims, H (Mrs Stokes) 1879-80 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Weld, M 1879-80 1911 Head Missionary MGC Magazine, Nov An Old Students Work in 1) November White, E 1879-80 School, Calcutta 1911 India' 1901 7 1881 MGC Magazine, Nov Atkins, E.T 1881 Gateshead-on-Tyne 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Atkinson, E 1881 Dublin 1911 Lecturer at King's College (Ladies MGC Magazine, Nov Buchheim, E.S 1881 Dept.) 1911 Assistant Mistress, MGC Magazine, Nov Wyggeston Girls' School, Codner, A.E 1881 Leicester 1911 Leicester March 1886 8 Croft Hill, Churnside, MGC Magazine, Nov Herriot, M 1881 Berwick 1911 Parkstrasse, 19, Metz- MGC Magazine, Nov Harcourt, O (Mrs Dörr) 1881 Montigny 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Hodge, F.M.S (Mrs Scott) 1881 Deceased 1911 3, Wellesley Road, MGC Magazine, Nov Jennings, A 1881 Sutton 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Ledger 1881 1911 MGC Magazine, Nov Oakeshott, E 1881 1911 Deceased March 1885 5 MGC Magazine, Nov Rundell, Emily 1881 1911 Ashdown, 1, Carew MGC Magazine, Nov Rundell, J (Mrs Rose) 1881 Road, Northwood 1911 Married July 1890 15 MGC Magazine, Nov Scammell, A 1881 S. -

Life Expectancy

HEALTH & WELLBEING Highgate November 2013 Life expectancy Longer lives and preventable deaths Life expectancy has been increasing in Camden and Camden England Camden women now live longer lives compared to the England average. Men in Camden have similar life expectancies compared to men across England2010-12. Despite these improvements, there are marked inequalities in life expectancy: the most deprived in 80.5 85.4 79.2 83.0 Camden will live for 11.6 (men) and 6.2 (women) fewer years years years years years than the least deprived in Camden2006-10. 2006-10 Men Women Belsize Longer life Hampstead Town Highgate expectancy Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Camden Town with Primrose Hill St Pancras and Somers Town Hampstead Town Camden Town with Primrose Hill Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Belsize West Hampstead Regent's Park Bloomsbury Cantelowes King's Cross Holborn and Covent Garden Camden Camden Haverstock average2006-10 average2006-10 Gospel Oak St Pancras and Somers Town Highgate Cantelowes England England Haverstock 2006-10 Holborn and Covent Garden average average2006-10 West Hampstead Regent's Park King's Cross Gospel Oak Bloomsbury Shorter life Kentish Town Kentish Town expectancy Kilburn Kilburn Note: Life expectancy data for 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 90 88 86 84 82 80 78 76 74 72 70 wards are not available for 2010-12. Life expectancy at birth (years) Life expectancy at birth (years) About 50 Highgate residents die Since 2002-06, life expectancy has Cancer is the main cause of each year2009-11. -

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures Brondesbury vs. North Middlesex North Middlesex vs. Brondesbury Sat. 8 May Richmond vs. Twickenham Sat. 10 July Twickenham vs. Richmond Overs games Teddington vs. Ealing Time games Ealing vs. Teddington 12.00 starts Crouch End vs. Shepherds Bush 11.00 starts Shepherds Bush vs. Crouch End Finchley vs. Hampstead Hampstead vs. Finchley Shepherds Bush vs. Richmond Richmond vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 15 May Ealing vs. Brondesbury Sat. 17 July Brondesbury vs. Ealing Overs games North Middlesex vs. Finchley Time games Finchley vs. North Middlesex 12.00 starts Twickenham vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Twickenham Hampstead vs. Crouch End Crouch End vs. Hampstead Brondesbury vs. Teddington Teddington vs. Brondesbury Sat. 22 May Richmond vs. Hampstead Sat. 24 July Hampstead vs. Richmond Overs games Crouch End vs. North Middlesex Time games North Middlesex vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Ealing 11.00 starts Ealing vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. Shepherds Bush Shepherds Bush vs. Twickenham Brondesbury vs. Finchley Finchley vs. Brondesbury Sat. 29 May Teddington vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 31 July Shepherds Bush vs. Teddington Overs games Ealing vs. Crouch End Time games Crouch End vs. Ealing 12.00 starts North Middlesex vs. Richmond 11.00 starts Richmond vs. North Middlesex Hampstead vs. Twickenham Twickenham vs. Hampstead Richmond vs. Ealing Ealing vs. Richmond Sat. 5 June Shepherds Bush vs. Hampstead Sat. 7 August Hampstead vs. Shepherds Bush Overs games Crouch End vs. Brondesbury Time games Brondesbury vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. -

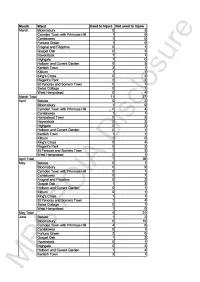

Month Ward Used to Injure Not Used to Injure March Bloomsbury 0 3

Month Ward Used to Injure Not used to injure March Bloomsbury 0 3 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 1 5 Cantelowes 1 0 Fortune Green 1 0 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 1 Gospel Oak 0 2 Haverstock 1 1 Highgate 1 0 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 3 1 Kilburn 1 1 King's Cross 0 2 Regent's Park 2 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 0 1 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 0 4 March Total 11 27 April Belsize 0 2 Bloomsbury 1 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 4 Cantelowes 1 1 Hampstead Town 0 2 Haverstock 2 3 Highgate 0 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kentish Town 1 1 Kilburn 1 0 King's Cross 0 4 Regent's Park 0 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 West Hampstead 0 1 April Total 7 36 May Belsize 0 1 Bloomsbury 0 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 1 Cantelowes 0 7 Frognal and Fitzjohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 1 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kilburn 0 1 King's Cross 1 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 4 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 1 0 May Total 4 31 June Belsize 1 2 Bloomsbury 0 1 0 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 4 6 Cantelowes 0 1 Fortune Green 2 0 Gospel Oak 1 3 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 2 Holborn and Covent Garden 1 4 Kentish Town 3 1 MPS FOIA Disclosure Kilburn 2 1 King's Cross 1 1 Regent's Park 2 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 Swiss Cottage 0 2 West Hampstead 0 1 June Total 18 39 July Bloomsbury 0 6 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 5 1 Cantelowes 1 3 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 2 0 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 4 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 1 0 King's Cross 0 3 Regent's Park 1 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 0 Swiss Cottage 1 2 West -

Dartmouth Park

Dartmouth Park Population: 7,656 Land area: 74.670 hectares December 2015 The maps contained in this document are used under licence A-Z: Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright and database rights OS 100017302 OS: © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OS 100019726 Strengths Social Only 21.8% of people over 65 live alone (Camden: 42.2%) Health & Well-being Mens' life expectancy is 82.9 years (Camden: 79 years) Women's life expectancy is 86.6 years (Camden: 84 years) Person's living in overcrowding: 13% (Camden: 20.2%) Environment & Transport 99.6% of homes have access to a regional park 100% of homes have access to a metroplitan park 99.9% of homes have access to a district park 100% of homes have access to nature Lowest annual air emmissions in Camden: - Particulate matter (PM10) range: 18.3 - Nitrogen oxide (NOx) range: 52.8 - Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) range: 33.8 Knowledge, Skills & Experience 98.4% of population can speak English well well or very well (Camden: 96.8%) Community Crimes rate is 63.5 per 1,000 residents (Camden 124.4 per 1,000) Challenges Society Ageing population: over 65s make up 14.5% of population (Camden: 10.9%) Economic Jobs per capita of working age residents: 0.2 jobs (Camden: 2.1 jobs per capita) Working age residents in receipt of ESA and Incapacity benefits: 10.5% (Camden: 6.4%) Total working age adults in receipt of out of work benefits: 15.7% (Camden: 9.3%) Environment & Transport Public transport accessinbility level score of 4.1 out of 8 (Camden 5.6) Multiple deprivation Lower super output areas* that fall within 10% most deprived in England (D'mouth Park = 5 LSOAs) Income deprivation (1 LSOA) Living environment deprivation (1 LSOA) Income deprivation affecting children (1 LSOA) * A lower super output area is a geography for the collection and publication of small area statistics. -

Swiss Cottage

Swiss Cottage Population: 16,297 Land area: 115.615 hectares December 2015 The maps contained in this document are used under licence A-Z: Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright and database rights OS 100017302 OS: © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OS 100019726 Strengths Social 90.5% of the population do not have a disability or long term health problem (Camden: 85.6%) Economic 71.6% of residents are economically active (Camden: 68.1%) Average annual household income is £60,211 (Camden: £52,962) Significant retail presence Swiss Cottage has a designated town centre Health & Well-being 49% of adults eat healthily (Camden: 41.6%) Knowledge, Skills & Experience 64% of pupils achieved KS4 GCSE 5+ A*-C inc English & maths (Camden: 59.9%) Community Significantly lower total crime rate than the Camden average: 70 (Camden: 124.4) Challenges Social Population density of 141 people per hectare (Camden: 105.4pph) Economic There are 0.7 jobs per capita of working age residents (Camden: 2.1 jobs per capita) The lowest average annual household income is £32,141 (S. Cottage: £60,211; Camden: £52,962 Very little childcare provision - 0.05 places per capita of children under 5 (Camden: 0.27 places) Health & Wellbeing 16% or reception class primary school children are overweight (Camden: 12%) Community Only 64.6% of under 5s are registered with Early Years (Camden: 79%) Multiple deprivation Lower super output areas* that fall within 10% most deprived in England (S. Cottage = 10 LSOAs) Income deprivation (1 LSOA) Health and disability deprivation (5 LSOAs) Living environment deprivation (3 LSOAs) Income deprivation affecting children (1 LSOA) Income deprivation affecting older people (1 LSOA) * A lower super output area is a geography for the collection and publication of small area statistics.