Has Student Voice Been Eliminated? a Consideration of Student Activism Post-Parkland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEVERAGAINMSD STUDENT ACTIVISM: LESSONS for AGONIST POLITICAL EDUCATION in an AGE of DEMOCRATIC CRISIS Kathleen Knight Abowitz

731 #NEVERAGAINMSD STUDENT ACTIVISM: LESSONS FOR AGONIST POLITICAL EDUCATION IN AN AGE OF DEMOCRATIC CRISIS Kathleen Knight Abowitz Department of Educational Leadership Miami University Dan Mamlok School of Education Tel Aviv University Abstract. In this essay, Kathleen Knight Abowitz and Dan Mamlok consider the arguments for agonist political education in light of a case study based in the events of the 2018 mass shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and the subsequent activism of its survivors. We use this case to examine agonist expressions of citizenship, and to present an argument for framing agonist politics through the lens of Deweyan transactional communication combined with the critical concept of articulation. A major lesson in this case is the significance of citizenship learning that prioritizes challenging the political status quo along with working to reestablish new political relations on grounds that are more just. The authors argue that the endgame of agonist-informed political education should be that which helps students, as present and future citizens, reconstruct existing political conditions. Knight Abowitz and Mamlok conclude with suggestions for four domains of knowledge and capacities that can productively shape agonist citizenship education efforts: political education, lived citizenship, critical political literacies, and critical digital literacies. Key Words. citizenship education; agonism; political emotion; transactionalism; articulation Introduction Philosophers of education have made good use of agonist critiques of democ- racy to propose reforms for school-based political and citizenship education. Ago- nist treatments of curriculum and pedagogy emphasize the importance of curricu- lum focused on the arts of disagreement and adversarial position-taking. -

Impacts of Service-Learning on Participating K-12 Students

Impacts of Service-Learning on Participating K-12 Students Source: RMC Research Corporation, December 2002, updated May 2007 For additional resources on this and other service‑learning topics visit Learn and Serve America’s National Service-Learning Clearinghouse at http://www.servicelearning.org. Recent research emphasizes academic, civic/citizenship, social/personal, and resilience impacts of service-learning on participating K-12 students. Academic Impacts A number of studies have been conducted showing promising results of the academic impact of service-learning. Students who participated in service-learning were found to have scored higher than nonparticipating students in several studies, particularly in social studies, writing, and English/language arts. They were found to be more cognitively engaged and more motivated to learn. Studies show great promise for service-learning as an avenue for increasing achievement among alternative school students and other students considered at risk of school failure. Studies on school engagement generally show that service-learning students are more cognitively engaged in school, but not necessarily more engaged behaviorally. Studies of students’ problem-solving abilities show strong increases in cognitive complexity and other related aspects of problem solving. Service-learning, then, does appear to have a positive impact on students by helping them to engage cognitively in school and score higher in certain content areas on state tests. Many of these outcomes are mediated by the quality of the program. For example: California Service-Learning Programs (Ammon, Furco, Chi & Middaugh, 2001) Researchers found that academic impacts were related to clarity of academic goals and activities, scope, and support through focused reflection. -

Iref Working Paper No. 202104 July 2021 in English

IREF Working Paper Series Offers they can’t refuse: a (negative) assessment of the impact on business and society at-large of the recent fortune of anti-discrimination laws and policies Riccardo de Caria IREF WORKING PAPER NO. 202104 JULY 2021 IN ENGLISH: EN.IREFEUROPE.ORG IN FRENCH: FR.IREFEUROPE.ORG IN GERMAN: DE.IREFEUROPE.ORG Institute f or Resear ch in Economic and Fiscal issues Riccardo de Caria (Università di Torino and IREF) Offers they can’t refuse: a (negative) assessment of the impact on business and society at-large of the recent fortune of anti-discrimination laws and policies July 2021 Abstract The article considers the relationship and balance between freedom of economic initiative and obligations deriving from anti-discrimination laws. After providing a theoretical framework of the problem of the limits to contractual autonomy arising from the horizontal application of fundamental rights (Drittwirkung), the work focuses on its most recent developments, especially in case law, from a comparative perspective. It identifies the paradoxes and logical inconsistencies that characterise the traditional approaches, and puts forward an alternative conceptual framework. 2 Offers they can’t refuse: a (negative) assessment of the impact on business and society at-large of the recent fortune of anti-discrimination laws and policies 1. The reference context: the horizontal application of fundamental rights Anti-discrimination law has progressively broadened the scope of protection limited to certain categories individuals, both through legislation and case law. This path towards what Italian legal philosopher Norberto Bobbio called ‘the age of rights’1 is generally welcomed by observers. -

Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society

Journal of Diversity in Higher Education © 2016 National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education 2016, Vol. 9, No. 3, 189–202 1938-8926/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000039 INTRODUCTION Student Activism, Diversity, and the Struggle for a Just Society Robert A. Rhoads University of California, Los Angeles This introductory article provides a historical overview of various student move- ments and forms of student activism from the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement to the present. Accordingly, the historical trajectory of student activism is framed in terms of 3 broad periods: the sixties, the postsixties, and the contem- porary context. The author pays particular attention to student organizing to address racial inequality as well as other forms of diversity. The article serves as an introduction to this special issue and includes a brief summary of the remainder of the issue’s content. Keywords: student activism, student movements, student organizing, social justice, campus-based inequality During the early 1990s, as a doctoral student campus, including in classrooms and residence in sociology and higher education, I began to halls. The students also participated in the 1993 systematically explore forms of activism and March on Washington for lesbian, gay, and direct action on the part of U.S. college stu- bisexual rights. I too joined the march and re- dents. My dissertation work focused on gay and corded many of the students’ experiences and bisexual males, including most notably their reflections, some of which are included in Com- coming out experiences and the subsequent en- ing Out in College. -

How Highly Competitive Colleges Admit Their Students

HOW HIGHLY COMPETITIVE COLLEGES ADMIT THEIR STUDENTS A typical admissions committee at a highly selective college meets throughout March to evaluate each applicant's record: (a) high school transcript (b) standardized test scores (Over 800 colleges and universities nationwide have eliminated or de- emphasized test scores in the admissions process because, according to a report published by the Educational Conservancy, “Test scores do not equal merit” and “high school achievement is paramount in the admissions equation.”) (c) recommendations from high school counselor, teachers (d) statement of primary interests and goals; student essay (e) student’s extracurricular activities (f) personal qualities as reflected in a college interview and through essays and recommendations (g) a student’s demonstrated interest in the school The application is generally read by three members of the admissions committee. The student, for example, may be rated on a scale of 1 to 5 on academic quality, personal strengths and extracurricular commitments, with 15 as a perfect score. In terms of academic quality, they want to know: can this person do the work here? What will this person contribute in the classroom? Has the student taken full advantage of the academic program at his/her school? Academic quality is the FIRST thing an admissions officer looks at when considering a candidate. Personal attributes are harder to measure. The admissions committee wants to determine what the student will contribute outside the classroom and how he/she stacks up on initiative, achievement, interests. Often the needs and priorities of the particular college carry considerable weight. Certain groups receive special consideration: athletes who are talented enough to play at the college level; minority students; and alumni children. -

Safe Schools Resource Guide & Activities Information on Known

Safe Schools Resource Guide & Activities Information on Known Planned Demonstrations and Walkouts March 14: #EnoughNationalSchoolWalkout: The Women’s March’s Youth EMPOWER group is planning a National School Walkout on March 14 to protest gun violence in schools and neighborhoods, according to the group’s website and @womensmarch. At 10 a.m. in every time zone, organizers are encouraging teachers, students, administrators, parents and supporters to walk out of school for 17 minutes — one minute for every person killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. March 24: #MarchForOurLives: On March 24, organizers of March for Our Lives are planning to march in Washington, D.C., to call for school safety and gun control. Organizers also are encouraging marches in local communities. Read more @AMarch4OurLives and at the group’s website: www.marchforourlives.com. April 20: #NationalSchoolWalkout: A National Day of Action Against Gun Violence in Schools is being planned for 10 a.m. on April 20, which is the 19th anniversary of the Columbine shooting. Plans and updates are currently being housed on Twitter at @schoolwalkoutUS and the National Network for Public Education website. Tips & Guidelines for School Leaders If/when you learn about student-led efforts, here are some quick tips for support: Remind Certificated & Classified personnel of district and site expectations for employees. Create a daily event schedule so when the anticipated protest day arrives, students will feel as if they have already achieved their activist goals. Meet with student leaders to assess needs and any plans. Remind students that counseling and guidance support are available to any student and that Fontana Unified encourages students to reach out. -

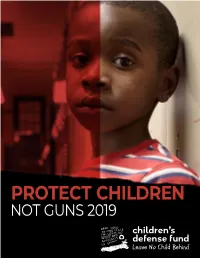

Protect Children, Not Guns 2019 1 Introduction

PROTECT CHILDREN NOT GUNS 2019 Mission Statement he Children’s Defense Fund Leave No Child Behind® mission is to ensure every child a T Healthy Start, a Head Start, a Fair Start, a Safe Start and a Moral Start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities. For over 40 years, CDF has provided a strong, effective and independent voice for all the children of America who cannot vote, lobby or speak for themselves. We pay particular attention to the needs of poor and minority children and those with disabilities. CDF educates the nation about the needs of children and encourages preventive investments before they get sick, drop out of school, get into trouble or suffer family breakdown. © 2019 Children’s Defense Fund. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................... 2 Overview .............................................................. 5 Select Shootings Involving Children in the Past 12 Months. 7 Child and Teen Gun Deaths ..........................................11 Child and Teen Gun Injuries .........................................19 International Gun Death Comparisons ..............................23 Progress Since Parkland .............................................29 We Can Do Better: We Must Strengthen Laws to Save Lives. .33 Stand Up and Take Action ...........................................39 Appendices .......................................................... 41 Endnotes ............................................................50 Protect Children, Not Guns 2019 1 Introduction On April 20, 1999, Americans witnessed a once unthinkable and now unforgettable tragedy at Columbine High School. We watched in horror as frightened children fled with their hands up, frantic parents tried to reunite with their children, and traumatized survivors told reporters about the violence they witnessed. It was the first time many of us saw these terrifying scenes. But it was far from the last. -

The Parkland Shooting.” It Too Can Be Understood As a Form of Civic Engagement

FROM THE INSTRUCTOR When the shooting broke out in Parkland, Florida, last February 14, Miranda was already underway with research for an essay about A Beautiful Mind, a 2001 film about the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash. Continuing with that worthy project would’ve been the easiest way for her complete the assignment. But in the wake of Parkland, Miranda’s motivation to understand the power of media representations of mental illness gave her the courage to change her approach midstream and to dive into a controversial political issue. Her choice paid off with the compelling and timely essay you are about to read. In Miranda’s words, “It is possible to start somewhere and then end up in a completely different place, and that is sometimes the best way to develop a project.” On March 24, as students across the country gathered for the March for Our Lives, Miranda was making the last round of revisions to her prizewinning essay “Representations of Mental Illness Within FOX and CNN: The Parkland Shooting.” It too can be understood as a form of civic engagement. In this paper, Miranda presents new data she collected about news coverage of the Parkland school shooting and uses the kind of critical information literacy skills that are essential to responsible citizenship. In doing so, she contributes to both scholarly and public conversations about gun violence and mental illness. Her portfolio makes the connection between scholarly and public discourse explicit when she describes how she drew on knowledge from her research to respond to an acquaintance’s Instagram post blaming gun violence on mentally ill people in especially derogatory terms. -

Understanding Persistence in the Resistance Authors: Dana R

Understanding Persistence in the Resistance Authors: Dana R. Fisher1 and Lorien Jasny2 Abstract Since Donald Trump’s Inauguration, large-scale protest events have taken place around the US, with many of the biggest events being held in Washington, DC. The streets of the nation’s capital have been flooded with people marching about a diversity of progressive issues including women’s rights, climate change, and gun violence. Although research has found that these events have mobilized a high proportion of repeat participants who come out again-and-again, limited research has focused on understanding differential participation in protest, especially during one cycle of contention. This paper, accordingly, explores the patterns among the protest participants to understand differential participation and what explains persistence in the Resistance. In it, we analyze a unique dataset collected from surveys conducted with a random sample of protest participant at the largest protest events in Washington, DC since the inauguration of Donald Trump. Our findings provide insights into repeat protesters during this cycle of contention. The paper concludes by discussion how our findings contribute to the research on differential participation and persistence. Keywords: protest, social movements, mobilization, persistence, the Resistance, 1 Department of Sociology, University of Maryland, 2112 Parren Mitchell Art-Sociology Building 3834 Campus Drive, College Park, MD 20742, [email protected] 2 Department of Politics, University of Exeter, Exeter, Devon UK EX4 4SB, [email protected] Introduction Since Donald Trump’s Inauguration, large-scale protest events have taken place around the US, with many of the biggest events being held in Washington, DC. -

Individual Claimsmaking After the Parkland Shooting* Deana A

Individual Claimsmaking after the Parkland Shooting* Deana A. Rohlinger, Ph.D. Professor of Sociology Florida State University Caitria DeLucchi Graduate Student in Sociology Florida State University Warren Allen, Ph.D. Teaching Faculty Rutgers University *We thank Sourabh Singh for his feedback on this paper. The lead author thanks her early morning “writing with randos” group for their support, including Beth Popp Berman, Danna Agmon, Christina Ho, Sarah Woulfin, Derek Gottlieb, Dahlia Remler, Dale Winling, Meredith Broussard, Adam Slez, Didem Turkoglu, Jason Windawi, Elizabeth Mazzolini, Jennifer Sessions, Louise Seamster, Daniel Hirschman. 1 On February 14, 2018, a former student killed 17 people and injured 17 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Some of the student survivors mobilized in protest of loose gun laws, and state legislatures across the country began passing bills to restrict gun access. This was true even in Florida, which is a testing-ground for National Rifle Association (NRA) legislation and whose Republican-dominated legislature often rejects modest restrictions on gun access. In less than a month, the legislature passed “the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act” (SB 7026), which raised the minimum age requirement for purchasing a firearm from 18 to 21, required a three-day waiting period for the purchase of a gun, prohibited the purchase and selling of bump stocks, expanded mental health services in the state, allocated monies to help harden schools, and funded a “marshal” program that allowed the arming of teachers and staff. Arguably, there are a number of reasons that the legislature opted for quick action. -

Toshalis & Nakkula, "Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice

MOTIVATION, ENGAGEMENT, AND APRIL 2012 STUDENT VOICE By Eric Toshalis and Michael J. Nakkula EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDENTS AT THE CENTER SERIES Students at the Center explores the role that student-centered approaches can play to deepen learning and prepare young people to meet the demands and engage the opportunities of the 21st century. Students at the Center synthesizes existing research on key components of student-centered approaches to learning. The papers that launch this project renew attention to the importance of engaging each student in acquiring the skills, knowledge, and expertise needed for success in college and a career. Student-centered approaches to learning, while recognizing that learning is a social activity, pay particular attention to the importance of customizing education to respond to each student’s needs and interests, making use of new tools for doing so. The broad application of student-centered approaches to learning has much in common with other education reform movements including closing the achievement gaps and providing equitable access to a high-quality education, especially for underserved youth. Student-centered approaches also align with emerging work to attain the promise and meet the demands of the Common Core State Standards. However, critical and distinct elements of student-centered approaches to learning challenge the current schooling and education paradigm: > Embracing the student’s experience and learning theory as the starting point of education; > Harnessing the full range of learning experiences at all times of the day, week, and year; > Expanding and reshaping the role of the educator; and > Determining progression based upon mastery. -

Student Voice and the Common Core

Student Voice and the Common Core SUSAN YONEZawa University of California, San Diego Replacing a discrete, sometimes lengthy list of topics to learn, the Common Core asks teachers to help students develop high-level cognitive skills: to per- sist, model, critique, reason, argue, explain, justify, and synthesize. Faced with this challenge, teachers are wondering what they can do to help students to meet the new standards and prepare for 21st-century careers. Research on student voice can provide some answers and inform the conversation about Common Core implementation. Over the past two decades, researchers, stu- dents, and educators have teamed up across a variety of projects and places to provide us with what kids say they need to engage deeply in their studies. Interestingly, what students have long told us they want in classroom cur- riculum and pedagogy resonates with Common Core principles. As educa- tors work to implement the Common Core, student voice can offer useful guidance as well as concrete examples of the schoolwork students find most challenging, engaging, relevant, and educational. The Common Core State Standards provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn, so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them. The stan- dards are designed to be robust and relevant to the real world, reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers. —Common Core State Standards Initiative mission statement If the reforms of the past 30 years have taught us nothing else, we know by now that theorizing about reform is far easier than enacting it.