The Effect of Direct Experience on Generating Insight Into and Deepening Understanding of Academic Topics Studied by High School Seniors in the Field" (2001)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of Organizational Structure and Pedagogical Approach: Online Versus Face-To-Face Donovan A

A Comparison of Organizational Structure and Pedagogical Approach: Online versus Face-to-face Donovan A. McFarlane, Frederick Taylor University Abstract This paper examines online versus face-to-face organizational structure and pedagogy in terms of education and the teaching and learning process. The author distinguishes several important terms related to distance/online/e-learning, virtual learning and brick-and-mortar learning interactions and concepts such as asynchronous and synchronous interactions, etc, before deliberating on perceived differences in organizational structure and pedagogical approaches of virtual and brick-and-mortar schools by examining organizational structure, knowledge and pedagogical theories, ideas, and constructs. The roles of mission, vision, and other considerations that contribute to differences between virtual and brick-and-mortar schools are examined. The appropriateness of structure and pedagogy as related to variables such as class size, span of control, and several other factors is discussed. The benefits and drawbacks of both virtual and brick-and-mortar schools are assessed in terms of perceived effectiveness and relation to perceived organizational structural and pedagogical differences before the author presents an informed response to the major thesis of this paper based on pertinent literature and the foregone discussion. After recognizing prevailing practices with regard to organizational structure and pedagogy, and given the pertinent role of technology and several influencing factors such -

Auburn, It's Time for the New Edward Little High School

Southern Maine’s Weekly Newspaper Now In Our 21st Year! WIN ITY © TwinT City TIMES, Inc. 2019 C TIMES(207) 795-5017 • [email protected] FREE • Vol. XXI, No. 10 Your Hometown Newspaper Since 1999 Thursday, June 6, 2019 • FREE Guest Column: Striving to deliver the quality 31st monument medical care we’d choose for our families unveiled at Memorial my many patients - in a ing. My current role allows much better way. With a me to serve them better. At Day Ceremony team of top oncologists, CMMC, we care for some radiologists, and surgeons, I very sick patients, but as would be able to help many the acuity of required care more people, and sicker increases, so does our ability people. Again, I’m working to help. I wanted to be part with folks I would want to of that, too. care for my family. Most satisfying to me At the same time, is when we are able to help healthcare in the State of a patient who has “fallen Prior to the ceremony, U.S. Senator Susan Collins walks in Maine is in transition, and through the cracks” while the Auburn Memorial Day Parade with the Grand Marshall, a lot of tough decisions are waiting for appointments at decorated Marine Colonel Todd Desgrosseilliers (retired). being made: bankruptcy other facilities. When I hear for some organizations, people wondering about During this year’s L-A less villages, small towns, elimination of services and CMMC’s reliability and Memorial Day Ceremony and big cities, we raise our consolidation for others. -

Internship Host Sites

Internship Host Sites 207 Lacrosse Biddeford Savings 360 Ventures Big Brothers Big Sisters A & L Labs Big Tree Hospitality A&E Real Estate Office Billerica Police Department AAA Northern New England Biodiversity Research Institute AARP Bioscience Association of Maine ABC Consultants Black Point Inn Albin Randall & Bennett Blue Wave AAU - Caterina Alternative Wellness Bonny Eagle High School Amistad Braun & Wilson Law Office ASL Live Music performances Bridgton Academy Atlantic Jet LLC. Broadturn Farm Auto Europe Brunswick & Topsham Water District Avesta Housing Build Maine Baker Company Buy Portland Baker Newman Noyes Camp Cedar Barbara Bush Children's Hospital Cancer Community Center Barker Enterprises - Wood Pellets Warehouse Canopy Farms Barry J. Brown, Attorney at Law Carahsoft Technology Bath Iron Works Catholic Charities Bath Middle School CEI Capital Management LLC Bath Savings Bank Center for Grieving Children Berlin City Auto Group Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Berman & Simmons, PA Central Maine Medical Center Berry Dunn Chellie Pingrie Berry Talbot Royer Cheverus High School BerryDunn Chiropractic & Sports Health Portland Internship Host Sites ChiroThin of Maine Easter Seals Cirrus Systems Inc. Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems City of Manomet Edward Little High School City of Saco Eimskip Clark Insurance Elmet Technologies Clover Preschool Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems Coastal Humane Society Energy Circle Coastal Orthopedics Engine Community Energy Partners Enterprise Rent-A-Car Compassus Hospice Falmouth High School Concord Group Insurance Fisher Engineering CoWorx Staffing Services Fitness & Performance Studio Creative Trails Fluid Imaging Technologies Cross Insurance Forager Cultivating Community Foreside Fitness Cumberland County Food Security Council Free Press D.L. Geary Brewing Fryeburg Fair: Interpreted Access Dawn D. -

Portland Maine City Council Meeting

ETHAN K. STRIMLING (MAYOR) KIMBERLY COOK (5) BELINDA S. RAY (1) JILL C. DUSON (AIL) SPENCER THIBODEAU (2) PIOUS ALI (AIL) BRIAN E. BATSON (3) NICHOLAS M. MAVO DONES, JR. (AIL) JUSTIN COSTA (4) AGENDA SPECIAL CITY COUNCIL MEETING FEBRUARY 21, 2018 The Portland City Council will hold a Special City Council Meeting at 6:00 p.m. in City Council Chambers, City Hall. The Honorable Ethan K. Strimling, Mayor, will preside. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: ROLL CALL: 6:00 P.M. PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD ON NON-AGENDA ITEMS: ANNOUNCEMENTS: RECOGNITIONS: APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING: (fab 1) February 5, 2018 Regular City Council Meeting Minutes PROCLAMATIONS: Proc 23-17/18 Proclamation Honoring Officer Jeffrey Druan as Police Officer of the (Tab 2) Month for December 2017 - Sponsored by Mayor Ethan K. Strimling. Proc 24-17/18 Proclamation Honoring Barron Center Skilled Nursing Facility (Tab 3) Sponsored by Mayor Ethan K, Strimling. APPOINTMENTS: Order 154-17/18 Order Appointing Members to Various Boards and Committees - (fab 4) Sponsored by the Nominating Committee, Councilor Pious Ali, Chair. The Nominating Committee met on January 31 and voted unanimously to forward this item to the City Council with a recommendation for passage. This order appoints the following individuals to various boards and committees: Term Name Committee Expires Luke Beland Police Citizen Review Subcommittee 03/30/2021 Mary Zwolinski Police Citizen Review Subcommittee 03/30/2021 Kristin Blum Portland Housing Authority Board 06/30/2023 Robin Tucker Portland Housing Authority Board 06/30/2019 Julia Tate Portland Historic Preservation Board 11/30/2018 Julie Landry Viola Portland Development Board 09/30/2019 Briana Volk Portland Development Board 09/30/2021 Nicole Gray Zoning Board of Appeals 12/31/2021 David Silk Planning Board 02/28/2021 Austin Smith Planning Board 02/28/2021 Sean Dundon Planning Board 02/28/2021 Lisa Bloss Creative Portland Board 11/30/2020 Nicole Barna Creative Portland Board 11/30/2021 Daniel McKrell Fair Hearing Officer 11/30/2021 Marpheen S. -

Wellness Research in NH Schools & Home School Environments.Pdf

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 2021- 2022 Wellness Research in NH Schools & Home School Environments RFP 2020- The New Hampshire Department of Education does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, marital status, national/ethnic origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, or disability in its programs, activities and employment practices. This statement is a reflection of the Department of Education and refers to, but is not limited to, the provisions of the following laws: Title IV, VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964- race color, national origin, The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, The Age Discrimination Act of 1975, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Title IX)-sex, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504)-disability, The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA)- disability, and NH Law against discrimination (RSA 354-A). Auxiliary aids and services are available upon request to individuals with disabilities. Section 1 – Overview and Schedule A. Executive Summary The purpose of this RFP is to seek proposals from individuals, agencies, institutions or organizations (hereafter referred to as applicant(s) to work with the NH Department of Education, Bureau of Student Wellness to conduct up to three research projects related to student wellness in NH school districts during the 21-22 Academic Year. These studies shall be conducted in a post COVID, post virtual learning environment. The three proposed studies are: Research Project #1: An Intervention Experiment Aimed at Increasing Play, Joy, Friendships, and Self- Efficacy Among Elementary School Students Research Project #2: A Survey and Focus-Group Study of Secondary Students’ Perceptions of Sources of School-Induced Distress and of How Schooling Could Be Improved Research Project #3: Surveys of Homeschooling Families Aimed at Learning Why They Have Chosen Homeschooling over Public Schooling Minimum Requirements: In order to be considered, the applicant must provide evidence of the following minimum requirements. -

The Learning Environment

Age-appropriate pedagogies Age-appropriate Pedagogies in the Early Years The learning environment As part of teachers’ decision-making processes The social environment they are encouraged to use a range and balance of pedagogical approaches when planning learning Building positive relationships with each young opportunities that promote active engagement, learner and their family sets the foundations for deep learning and positive dispositions to learning. an environment of trust and respect to flourish. Teachers are also encouraged to reflect critically on Encouraging relationships to develop between the relationships between the learning environment learners, and promoting respectful relationships and their practices. The organisation of the learning with all members of the school community supports environment, the expectations teachers set, the young learners to develop a sense of belonging. routines, and ways of interacting with young learners Feeling safe and supported is integral to the reflect teachers’ beliefs and values shaping the wellbeing of all learners. classroom culture that is established (Curtis & Carter, 2008). The culture of the classroom is instrumental The social environment: in influencing the dispositions that young learners Teaching suggestions develop to learning. Building a supportive classroom climate takes time To maximise learning possibilities and positive and flexibility as routines, expectations and accepted dispositions to learning, priority is given to creating ways of interacting with peers and adults are learning environments that are motivating, engaging, established and maintained. flexible, inviting, challenging and supportive for • Discuss daily routines regularly so that young young learners. As part of this process early years learners develop a sense of routine and know teachers deliberately, purposefully and thoughtfully what to expect. -

A Brief History of Progressive Education

A Brief History of Progressive Lesson 2: Education in America before Education Progressive Education with Dr. Jason Edwards Outline: “How did we get to where we are today?” “Education then, beyond all other devices of human origin, is the great equalizer of the conditions of men, the balance-wheel of the social machinery.” Horace Mann “The fruit of liberal education is not learning, but the capacity and desire to learn, not knowledge, but power.” Charles William Elliot Core Elements of Progressive Education Publicly funded school system School is standardized and made universally obligatory. School is understood as not simply academics. School is understood as a means towards perfecting society. School is understood as a learning environment centered on the student’s interests. School is understood as a learning environment guided by applied scientific research. School is understood and designed to be a learning environment aimed at facilitating vocational development (i.e. job preparation). Women are accepted as teachers, specifically elementary school teachers. School involves a “differentiated curriculum”. Federal government directly involved in education. Schools based on the “German specialist model” of education; (i.e. not the liberal arts - the focus instead is on specialists). School is about developing “new” knowledge, rather than the transmission of knowledge through generations. Progressive education is based, in part, on Romanticism, (Ex. Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Emile) basic assumptions in progressive education’s “anthropology”: o The child is not understood as a fallen human being but understood as naturally innocent and oppressed human being. o Children are understood to be “active” learners. Nature is more important than books. -

Learning Environment: an Overview

Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences Education, 27(National Teacher Standards 4), 2009 Standard 7: Fox Learning Environment: An Overview Candace K. Fox Mount Vernon Nazarene University Learning Environments, Standard 7 challenges the beginning family and consumer sciences teacher to “create and implement a safe, supportive learning environment that shows sensitivity to diverse needs, values, and characteristics of students, families, and communities” (National Association of Teacher Educators for Family and Consumer Sciences [NATEFACS], 2004). In this article, several theoretical components of learning environments are explored as a foundation for grappling with this broad Standard. Resources that provide background material and specific ideas are listed to help beginning teachers as they work to establish quality learning environments. Also included is an annotated bibliography addressing values, character education, and emotional intelligence; safety and caring issues; and a variety of diversity topics including race and ethnicity, gender, and poverty. Introduction The beginning family and consumer sciences teacher must be able to demonstrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes to enable student learning in four broad content areas: (a) career, community, and family connections; (b) consumer economics and family resources; (c) family and human development; and (d) nutrition, food, and wellness. Additionally, six professional practice standards are outlined including the theme of this article, the Learning Environment. Specifically, -

Chapter ?:5: Designing the Subtitle Learning Environment

Chapter ?:5: Designing the Subtitle Learning Environment Chapter 5: Designing the Learning Environment Guiding Principle: The Environment The Kindergarten environment allows complex, rich play to thrive. It is a warm and inviting place where children and adults inquire, learn, and co -construct together. Children’s natural curiosity and inquisitiveness are nurtured in learning environments that encourage active, explorative play and sustained peer interactions. The Kindergarten environment—including its physical, social, and organizational qualities, both indoors and outdoors—plays an integral role in children’s learning. Teachers create a multi-sensory, enabling “In order to act as an environment that supports emergent literacy educator for the child, and numeracy. They recognize children’s the environment has different learning styles and many ways of knowing. Children benefit from repeated to be flexible: it must opportunities to represent their ideas through undergo frequent playing with blocks, engaging in dramatic play, modification by the documenting, writing, painting, and drawing. children and the Children make choices and engage in play teachers in order to in a rich learning environment designed to extend and build upon their interests and the remain up-to-date and Kindergarten curricular goals. The environment responsive to their reflects the diversity of the children, their needs to be protagonists families, and their communities. Teachers value in constructing outdoor play, recognizing its potential for the their knowledge” highest level of development and learning in young children. (Gandini 177). Guiding Principle: The Schedule Kindergarten scheduling is responsive to children’s changing needs, allowing a developmentally appropriate curriculum to emerge over time. The daily Kindergarten schedule includes at least one hour of child-directed, adult-supported playtime to allow for deep and engaging play experiences. -

21St Century Learning Nicole Ondrashek Northwestern College - Orange City

Northwestern College, Iowa NWCommons Master's Theses & Capstone Projects Education 5-2017 21st Century Learning Nicole Ondrashek Northwestern College - Orange City Follow this and additional works at: https://nwcommons.nwciowa.edu/education_masters Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Ondrashek, N. (2017). 21st century learning (Master's thesis, Northwestern College, Orange City, IA). Retrieved from http://nwcommons.nwciowa.edu/education_masters/21/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Education at NWCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses & Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of NWCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: 21st CENTURY LEARNING 1 21st Century Learning Nicole Ondrashek Northwestern College May 2017 Running head: 21st CENTURY LEARNING 2 Abstract Research has shown that students who are taught using 21st century teaching styles are more successful throughout their education. This literature review explores the importance of 21st century learning and teaching styles. This review begins by looking into and discussing the role of the teacher in a 21st century learning environment. The role of the teacher is to be a guide by the student’s side. This review provides ways to be that guide, rather than the instructor. This literature review also looks at the benefits of flexible seating and how the teacher can create a classroom using flexible seating. Finally this review looks at the importance of integrating meaningful technology use into student learning. This includes virtual field trips, Genius Hour and Makers Space. Keywords: 21st century learning, flexible seating, technology integration, Genius Hour. -

The Case for Fortified Teaching and Learning Environments

Fall 2013 180the News from Turnaround for Children The Case for Fortified Teaching and Learning Environments Raising Awareness From New York, to Chicago, to Aspen By Pamela Cantor, M.D., President and CEO, Turnaround for Children and beyond, Turnaround for Children staff, teachers, and students have earned exciting opportunities to lead and participate in high level conversa- tions about innovative approaches to solving the problem of chronically underperforming public schools serving children growing up in poverty. Education Nation: What It Takes NBC News invited Dr. Pamela Cantor to be a featured speaker at Education Nation, the summit of top thought leaders and influ- encers in education, government, business, philanthropy, and media, broadcast from The New York Public Library. In a discussion entitled, “What it Takes: Safe Schools,” moderated by Hoda Kotb, Cantor painted a vivid picture of the climate and culture Today, one in four children in the United Our nation’s underperforming schools share schools need to create for students to thrive. States is growing up in poverty. Many are common challenges: children unready to exposed to violence, chronic insecurity, loss, learn, teachers unprepared to teach students and disruption. Poverty inflicts a traumatic with intense needs, and principals ill equipped form of stress on their developing brains. It to act against such adversity. Collectively, interferes with learning. It impacts behavior. these challenges pose a pattern of risk: It undermines belief. risk to student development, classroom instruction, and schoolwide culture, each Children don’t shed what they have exper- capable of derailing academic achievement. ienced at the schoolhouse door. It all shows up in the classroom. -

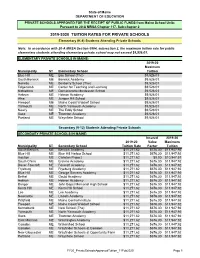

2019-2020 TUITION RATES for PRIVATE SCHOOLS Elementary (K-8) Students Attending Private Schools

State of Maine DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PRIVATE SCHOOLS APPROVED FOR THE RECEIPT OF PUBLIC FUNDS from Maine School Units Pursuant to 20-A MRSA Chapter 117, Sub-chapter 2 2019-2020 TUITION RATES FOR PRIVATE SCHOOLS Elementary (K-8) Students Attending Private Schools Note: In accordance with 20-A MRSA Section 5804, subsection 2, the maximum tuition rate for public elementary students attending elementary private school may not exceed $9,526.01. ELEMENTARY PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN MAINE: 2019-20 Maximum Municipality ST Elementary School Tuition Blue Hill ME Bay School (The) $9,526.01 South Berwick ME Berwick Academy $9,526.01 Norway ME Boxberry School (The) $9,526.01 Edgecomb ME Center for Teaching and Learning $9,526.01 Nobleboro ME Damariscotta Montessori School $9,526.01 Hebron ME Hebron Academy $9,526.01 Alna ME Juniper Hill School $9,526.01 Freeport ME Maine Coast Waldorf School $9,526.01 Yarmouth ME North Yarmouth Academy $9,526.01 Newry ME The Eddy School $9,526.01 Saco ME Thornton Academy $9,526.01 Portland ME Waynflete School $9,526.01 Secondary (9-12) Students Attending Private Schools SECONDARY PRIVATE SCHOOLS IN MAINE: Insured 2019-20 2019-20 Value Maximum Municipality ST Secondary School Tuition Rate Factor Tuition South Berwick ME Berwick Academy $11,271.62 $676.30 $11,947.92 Blue Hill ME Blue Hill Harbor School $11,271.62 $676.30 $11,947.92 Houlton ME Carleton Project $11,271.62 $0.00 $10,947.57 South China ME Erskine Academy $11,271.62 $676.30 $11,947.92 Dover-Foxcroft ME Foxcroft Academy $11,271.62 $676.30 $11,947.92 Fryeburg ME