British Phenological Records Indicate High Diversity and Extinction Rates Among LateSummerFlying Pollinators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diptera) of North-Eastern North America

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e36673 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e36673 Taxonomic Paper New Syrphidae (Diptera) of North-eastern North America Jeffrey H. Skevington‡,§, Andrew D. Young|, Michelle M. Locke‡, Kevin M. Moran‡,§ ‡ AAFC, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Canada § Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada | California Department of Food and Agriculture, Sacramento, United States of America Corresponding author: Jeffrey H. Skevington ([email protected]) Academic editor: Torsten Dikow Received: 31 May 2019 | Accepted: 09 Aug 2019 | Published: 03 Sep 2019 Citation: Skevington JH, Young AD, Locke MM, Moran KM (2019) New Syrphidae (Diptera) of North-eastern North America. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e36673. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e36673 ZooBank: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:823430AD-B648-414F-A8B2-4F1E5F1A086A Abstract Background This paper describes 11 of 18 new species recognised in the recent book, "Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America". Four species are omitted as they need to be described in the context of a revision (three Cheilosia and a Palpada species) and three other species (one Neoascia and two Xylota) will be described by F. Christian Thompson in a planned publication. Six of the new species have been recognised for decades and were treated by J. Richard Vockeroth in unpublished notes or by Thompson in his unpublished but widely distributed "A conspectus of the flower flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) of the Nearctic Region". Five of the 11 species were discovered during the preparation of the Field Guide. Eight of the 11 have DNA barcodes available that support the morphology. New information New species treated in this paper include: Anasimyia diffusa Locke, Skevington and Vockeroth (Smooth-legged Swamp Fly), Anasimyia matutina Locke, Skevington and This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC0 Public Domain Dedication. -

Insecta: Hymenoptera: Vespoidea) Türleri Üzerine Faunistic Araştirmalar Ve Ekolojik Gözlemler

ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ ADANA İLİ VESPIDAE (INSECTA: HYMENOPTERA: VESPOIDEA) TÜRLERİ ÜZERİNE FAUNİSTİC ARAŞTIRMALAR VE EKOLOJİK GÖZLEMLER Samet Eray YALNIZ BİYOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI ANKARA 2018 Her hakkı saklıdır ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi ADANA İLİ VESPIDAE (INSECTA: HYMENOPTERA: VESPOIDEA) TÜRLERİ ÜZERİNE FAUNİSTİC ARAŞTIRMALAR VE EKOLOJİK GÖZLEMLER Samet Eray YALNIZ Ankara Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Biyoloji Anabilim Dalı Danışman: Prof. Dr Ayla TÜZÜN Bu çalışma 2017 yılı Haziran - Ekim aylarında Adana il merkezi ve ilçelerinden toplanan 1296 Vespidae (Insecta: Hymenoptera) örneğine dayanmaktadır. Çalışmada, taksonların sistematik açıdan önemli olan vücut kısımları çizilmiş, yatay ve dikey dağılışları, ekolojileri ve fenolojileri ile Türkiye ve dünyadaki yayılışları verilmiştir. Çalışmada Adana ili ve çevresinden Vespinae altfamilyasına ait 5 tür: Vespa crabro Linnaeus, 1758; Vespa orientalis Linnaeus, 1771; Vespula (Paravespula) germanica (Fabricius, 1793); Vespula (Paravespula) vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758); Dolichovespula (Metavespula) sylvestris (Scopoli, 1763); Polistinae altfamilyasından 5 tür: Polistes (Polistes) associus Kohl, 1898; Polistes (Polistes) biglumis (Linnaeus, 1758); Polistes (Polistes) dominula (Christ, 1791); Polistes (Polistes) gallicus (Linnaeus, 1767); Polistes (Polistes) nimpha (Christ, 1791) ve Eumeninae altfamilyasından 14 tür: Delta unguiculatum unguiculatum (Villers, 1789); Eumenes dubius dubius Saussure, 1852; Ancistrocerus auctus (Fabricius, 1793); Allodynerus floricola -

Biological Diversity and Conservation ISSN

www.biodicon.com Biological Diversity and Conservation ISSN 1308-8084 Online; ISSN 1308-5301 Print 12/2 (2019) 15-22 Research article/Araştırma makalesi DOI: 10.5505/biodicon.2019.09709 The faunistic studies on Vespidae species (Hymenoptera: Vespoidea) of Adana province, Turkey Samet Eray YALNIZ *1, Ayla TÜZÜN 2 ORCID: 0000000228996271; 0000000197954860 1 Ankara University, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Department of Biology, Ankara, Turkey 2 Ankara University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ankara, Turkey Abstract This study was performed with 1296 specimens of Vespidae collected from Adana province and its districts in 2017 during June and October. At the end of the study, 24 species and subspecies were collected from the subfamilies Vespinae, Polistinae and Eumeninae. Vespa crabro Linnaeus, 1758; Vespula (Paravespula) vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758); Polistes (Polistes) associus Kohl, 1898; Polistes (Polistes) biglumis (Linnaeus, 1758); Allodynerus floricola floricola (de Saussure, 1853); Eumenes pomiformis (Fabricius, 1781); Ancistrocerus longispinosus (de Saussure, 1855); Ancistrocerus parietum (Linnaeus, 1758) and Symmorphus (Symmorphus) gracilis (Brullé, 1833) were reported as new records for Adana province. In this study, it is aimed to contribute to the Vespidae fauna of Adana province. Key words: social wasps, systematic, Vespinae, Polistinae, Eumeninae ---------- ---------- Adana ili Vespidae türleri (Hymenoptera: Vespoidea) üzerine faunistik araştırmalar Özet Bu çalışma 2017 yılı Haziran - Ekim aylarında -

Diversity and Resource Choice of Flower-Visiting Insects in Relation to Pollen Nutritional Quality and Land Use

Diversity and resource choice of flower-visiting insects in relation to pollen nutritional quality and land use Diversität und Ressourcennutzung Blüten besuchender Insekten in Abhängigkeit von Pollenqualität und Landnutzung Vom Fachbereich Biologie der Technischen Universität Darmstadt zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doctor rerum naturalium genehmigte Dissertation von Dipl. Biologin Christiane Natalie Weiner aus Köln Berichterstatter (1. Referent): Prof. Dr. Nico Blüthgen Mitberichterstatter (2. Referent): Prof. Dr. Andreas Jürgens Tag der Einreichung: 26.02.2016 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 29.04.2016 Darmstadt 2016 D17 2 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit entsprechend den Regeln guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis selbständig und ohne unzulässige Hilfe Dritter angefertigt habe. Sämtliche aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommene Gedanken sowie sämtliche von Anderen direkt oder indirekt übernommene Daten, Techniken und Materialien sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher keiner anderen Hochschule zu Prüfungszwecken eingereicht. Osterholz-Scharmbeck, den 24.02.2016 3 4 My doctoral thesis is based on the following manuscripts: Weiner, C.N., Werner, M., Linsenmair, K.-E., Blüthgen, N. (2011): Land-use intensity in grasslands: changes in biodiversity, species composition and specialization in flower-visitor networks. Basic and Applied Ecology 12 (4), 292-299. Weiner, C.N., Werner, M., Linsenmair, K.-E., Blüthgen, N. (2014): Land-use impacts on plant-pollinator networks: interaction strength and specialization predict pollinator declines. Ecology 95, 466–474. Weiner, C.N., Werner, M , Blüthgen, N. (in prep.): Land-use intensification triggers diversity loss in pollination networks: Regional distinctions between three different German bioregions Weiner, C.N., Hilpert, A., Werner, M., Linsenmair, K.-E., Blüthgen, N. -

Виды Рода Agenioideus Ashmead, 1902 (Hymenoptera, Pompilidae) Фауны Беларуси

Общая биология Выпуск 6/2018 9 УДК 595.794.23(476) А. С. Шляхтёнок Государственное научно-производственное объединение «Научно-практический центр Национальной академии наук Беларуси по биоресурсам», ул. Академическая, 27, 220072 Минск, Республика Беларусь, [email protected] ВИДЫ РОДА AGENIOIDEUS ASHMEAD, 1902 (HYMENOPTERA, POMPILIDAE) ФАУНЫ БЕЛАРУСИ В результате 30-летних сборов в регионе отловлено 215 экземпляров ос рода Agenioideus, относящихся к двум видам: A. cinctellus (98,7%) и A. sericeus (1,3%). A. cinctellus встречается на всей территории республики, а A. sericeus обнаружен только в её южной части. Виды, зарегистрированные на территории Беларуси, обитают преимущественно в открытых биотопах. Наибольшая активность выявленных видов приходится на июль. На основании изучения полученного материала и литературных источников, была составлена определительная таблица из 6 видов рода Agenioideus. Работа выполнена при поддержке Белорусского республиканского фонда фундаментальных исследований (договор № Б15-049). Ключевые слова: Беларусь; фауна; экология; Hymenoptera; Pompilidae; Agenioideus; определительная таблица; распространение. Рис. 24. Библиогр.: 15 назв. A. S. Shlyakhtyonok The Scientific and Practical Center for Bioresources of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, 27, Akademicheskaya str., 220072 Minsk, Belarus, [email protected] THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS AGENIOIDEUS ASHMEAD, 1902 (HYMENOPTERA, POMPILIDAE) OF THE BELARUSIAN FAUNA As a result of 30-year gathering in the region, 215 specimens of the genus Agenioideus, belonging to two species, were caught: A. cinctellus (98.7%) and A. sericeus (1.3%). A. cinctellus is found throughout the entire territory of the republic, and A. sericeus is found only in its southern part. The species registered in Belarus live mainly in open biotopes. The peak of activity of the identified species is in July. -

Helophilus Affinis, a New Syrphid Fly for Belgium (Diptera: Syrphidae)

Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie/Bulletin van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Entomologie, 150 (2014) : 37-39 Helophilus affinis , a new syrphid fly for Belgium (Diptera: Syrphidae) Frank VAN DE MEUTTER , Ralf GYSELINGS & Erika VAN DEN BERGH Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Kliniekstraat 25, B-1070 Brussel (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]) Abstract A male Helophilus affinis Wahlberg, 1844 was caught on 7 July 2012 at the nature reserve Putten Weiden at Kieldrecht. This species is new to Belgium. In this contribution we provide an account of this observation and discuss the occurrence of Helophilus affinis in Western-Europe. Keywords: faunistics, freshwater species, range shift, Syrphidae. Samenvatting Op 7 juli 2012 werd een mannetje van de Noordse pendelvlieg Helophilus affinis Wahlberg, 1844 verzameld in het gebied Putten Weiden te Kieldrecht. Deze soort is nieuw voor België. Deze bijdrage geeft een beschrijving van deze vangst en beschrijft het voorkomen van deze soort in West-Europa. Résumé Le 7 Juillet 2012, un mâle de Helophilus affinis Wahlberg, 1844 fut observé à Kieldrecht. Cette espèce est signalée pour la première fois de Belgique. La répartition de l’espèce en Europe de l’Ouest est discutée. Introduction Over the last 20 years, the list of Belgian syrphids on average has grown by one species each year (V AN DE MEUTTER , 2011). About one third of these additions, however, is due to changes in taxonomy i.e. they do not indicate true changes in our fauna. Among the other species that are newly recorded, we find mainly xylobionts and southerly species expanding their range to the north. -

Hoverfly Newsletter No

Dipterists Forum Hoverfly Newsletter Number 48 Spring 2010 ISSN 1358-5029 I am grateful to everyone who submitted articles and photographs for this issue in a timely manner. The closing date more or less coincided with the publication of the second volume of the new Swedish hoverfly book. Nigel Jones, who had already submitted his review of volume 1, rapidly provided a further one for the second volume. In order to avoid delay I have kept the reviews separate rather than attempting to merge them. Articles and illustrations (including colour images) for the next newsletter are always welcome. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 49 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2010 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email:[email protected], to reach me by 20 May 2010. Please note the earlier than usual date which has been changed to fit in with the new bulletin closing dates. although we have not been able to attain the levels Hoverfly Recording Scheme reached in the 1980s. update December 2009 There have been a few notable changes as some of the old Stuart Ball guard such as Eileen Thorpe and Austin Brackenbury 255 Eastfield Road, Peterborough, PE1 4BH, [email protected] have reduced their activity and a number of newcomers Roger Morris have arrived. For example, there is now much more active 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire, PE9 1QE, recording in Shropshire (Nigel Jones), Northamptonshire [email protected] (John Showers), Worcestershire (Harry Green et al.) and This has been quite a remarkable year for a variety of Bedfordshire (John O’Sullivan). -

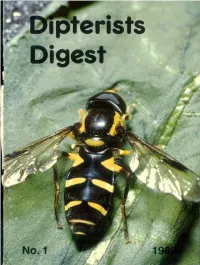

Ipterists Digest

ipterists Digest Dipterists’ Digest is a popular journal aimed primarily at field dipterists in the UK, Ireland and adjacent countries, with interests in recording, ecology, natural history, conservation and identification of British and NW European flies. Articles may be of any length up to 3000 words. Items exceeding this length may be serialised or printed in full, depending on the competition for space. They should be in clear concise English, preferably typed double spaced on one side of A4 paper. Only scientific names should be underlined- Tables should be on separate sheets. Figures drawn in clear black ink. about twice their printed size and lettered clearly. Enquiries about photographs and colour plates — please contact the Production Editor in advance as a charge may be made. References should follow the layout in this issue. Initially the scope of Dipterists' Digest will be:- — Observations of interesting behaviour, ecology, and natural history. — New and improved techniques (e.g. collecting, rearing etc.), — The conservation of flies and their habitats. — Provisional and interim reports from the Diptera Recording Schemes, including provisional and preliminary maps. — Records of new or scarce species for regions, counties, districts etc. — Local faunal accounts, field meeting results, and ‘holiday lists' with good ecological information/interpretation. — Notes on identification, additions, deletions and amendments to standard key works and checklists. — News of new publications/references/iiterature scan. Texts concerned with the Diptera of parts of continental Europe adjacent to the British Isles will also be considered for publication, if submitted in English. Dipterists Digest No.1 1988 E d ite d b y : Derek Whiteley Published by: Derek Whiteley - Sheffield - England for the Diptera Recording Scheme assisted by the Irish Wildlife Service ISSN 0953-7260 Printed by Higham Press Ltd., New Street, Shirland, Derby DE5 6BP s (0773) 832390. -

Hoverfly Newsletter 67

Dipterists Forum Hoverfly Newsletter Number 67 Spring 2020 ISSN 1358-5029 . On 21 January 2020 I shall be attending a lecture at the University of Gloucester by Adam Hart entitled “The Insect Apocalypse” the subject of which will of course be one that matters to all of us. Spreading awareness of the jeopardy that insects are now facing can only be a good thing, as is the excellent number of articles that, despite this situation, readers have submitted for inclusion in this newsletter. The editorial of Hoverfly Newsletter No. 66 covered two subjects that are followed up in the current issue. One of these was the diminishing UK participation in the international Syrphidae symposia in recent years, but I am pleased to say that Jon Heal, who attended the most recent one, has addressed this matter below. Also the publication of two new illustrated hoverfly guides, from the Netherlands and Canada, were announced. Both are reviewed by Roger Morris in this newsletter. The Dutch book has already proved its value in my local area, by providing the confirmation that we now have Xanthogramma stackelbergi in Gloucestershire (taken at Pope’s Hill in June by John Phillips). Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 68 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2020 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email:[email protected], to reach me by 20 June 2020. The hoverfly illustrated at the top right of this page is a male Leucozona laternaria. -

Checklist of the Spider Wasps (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae) of British Columbia

Checklist of the Spider Wasps (Hymenoptera: Pompilidae) of British Columbia Scott Russell Spencer Entomological Collection Beaty Biodiversity Museum, UBC Vancouver, B.C. The family Pompilidae is a cosmopolitan group of some 5000 species of wasps which prey almost exclusively on spiders, giving rise to their common name - the spider wasps. While morphologically monotonous (Evans 1951b), these species range in size from a few millimetres long to among the largest of all hymenopterans; genus Pepsis, the tarantula hawks may reach up to 64 mm long in some tropical species (Vardy 2000). B.C.'s largest pompilid, Calopompilus pyrrhomelas, reaches a more modest body length of 19 mm among specimens held in our collection. In North America, pompilids are known primarily from hot, arid areas, although some species are known from the Yukon Territories and at least one species can overwinter above the snowline in the Colorado mountains (Evans 1997). In most species, the females hunt, attack, and paralyse spiders before laying one egg on (or more rarely, inside) the spider. Prey preferences in Pompilidae are generally based on size, but some groups are known to specialize, such as genus Ageniella on jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) and Tachypompilus on wolf spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae) (Evans 1953). The paralysed host is then deposited in a burrow, which may have been appropriated from the spider, but is typically prepared before hunting from existing structures such as natural crevices, beetle tunnels, or cells belonging to other solitary wasps. While most pompilids follow this general pattern of behaviour, in the Nearctic region wasps of the genus Evagetes and the subfamily Ceropalinae exhibit cleptoparasitism (Evans 1953). -

Podalonia Affinis on the Sefton Coast in 2019

The status and distribution of solitary bee Stelis ornatula and solitary wasp Podalonia affinis on the Sefton Coast in 2019 Ben Hargreaves The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside October 2019 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to Tanyptera Trust for funding the research and to Natural England, National Trust and Lancashire Wildlife Trust for survey permissions. 2 CONTENTS Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Aims and objectives………………………………………………………………………….6 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Results……………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Discussion………………………………………………………………………………………..9 Follow-up work………………………………………………………………………………11 References……………………………………………………………………………………..11 3 SUMMARY The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside (Lancashire Wildlife Trust) were commissioned by Liverpool Museum’s Tanyptera project to undertake targeted survey of Nationally Rare (and regionally rare) aculeate bees and wasps on various sites on the Sefton Coast. Podalonia affinis is confirmed as extant on the Sefton Coast; it is definitely present at Ainsdale NNR and is possibly present at Freshfield Dune Heath. Stelis ornatula, Mimesa bruxellensis and Bombus humilis are not confirmed as currently present at the sites surveyed for this report. A total of 141 records were made (see attached data list) of 48 aculeate species. The majority of samples were of aculeate wasps (Sphecidae, Crabronidae and Pompilidae). 4 INTRODUCTION PRIMARY SPECIES (Status) Stelis ornatula There are 9 records of this species for VC59 between 1975 and 2000. All the records are from the Sefton Coast. The host of this parasitic species is Hoplitis claviventris which is also recorded predominantly from the coast (in VC59). All records are from Ainsdale National Nature Reserve (NNR) and Formby (Formby Point and Ravenmeols Dunes). Podalonia affinis There are 15 VC59 records for this species which includes both older, unconfirmed records and more recent confirmed records based on specimens. -

Bees and Wasps of the East Sussex South Downs

A SURVEY OF THE BEES AND WASPS OF FIFTEEN CHALK GRASSLAND AND CHALK HEATH SITES WITHIN THE EAST SUSSEX SOUTH DOWNS Steven Falk, 2011 A SURVEY OF THE BEES AND WASPS OF FIFTEEN CHALK GRASSLAND AND CHALK HEATH SITES WITHIN THE EAST SUSSEX SOUTH DOWNS Steven Falk, 2011 Abstract For six years between 2003 and 2008, over 100 site visits were made to fifteen chalk grassland and chalk heath sites within the South Downs of Vice-county 14 (East Sussex). This produced a list of 227 bee and wasp species and revealed the comparative frequency of different species, the comparative richness of different sites and provided a basic insight into how many of the species interact with the South Downs at a site and landscape level. The study revealed that, in addition to the character of the semi-natural grasslands present, the bee and wasp fauna is also influenced by the more intensively-managed agricultural landscapes of the Downs, with many species taking advantage of blossoming hedge shrubs, flowery fallow fields, flowery arable field margins, flowering crops such as Rape, plus plants such as buttercups, thistles and dandelions within relatively improved pasture. Some very rare species were encountered, notably the bee Halictus eurygnathus Blüthgen which had not been seen in Britain since 1946. This was eventually recorded at seven sites and was associated with an abundance of Greater Knapweed. The very rare bees Anthophora retusa (Linnaeus) and Andrena niveata Friese were also observed foraging on several dates during their flight periods, providing a better insight into their ecology and conservation requirements.