Of Fa Illufitc ^Cadi'mw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Master of Performing Arts (Vocal & Instrumental)

MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (VOCAL & INSTRUMENTAL) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (Applied Theory) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To critically appreciate a music concert. 2. To understand and compare the ragas and talas prescribed for practical’s. 3. To write compositions in the prescribed notation system. 4. To introduce students to staff notation. Course Content:- I. Theoretical study of Ragas and Talas prescribed for practical and their comparative study wherever possible. II. Reading and writing of Notations of compositions Alap, Taan etc. in the Ragas and Talas with prescribed Laykraries. III. Elementary Knowledge of Staff Notation. IV. Critical appreciation of Music concert. Bibliographies:- a. Dr. Bahulkar, S. Kalashastra Visharad (Vol. 1 - 4 ). Mumbai:: Sanskar Prakashan. b. Dr. Sharma, M. Music India. A. B. H. Publishing Hoouse. c. Dr. Vasant. Sangeet Visharad. Hatras:: Sangeet Karyalaya. d. Rajopadhyay, V. Sangeet Shastra. Akhil Bhartiya Gandharva Vidhyalaya e. Rathod, B. Thumri. Jaipur:: University Book House Pvt. Ltd. f. Shivpuji, G. Lay Shastra. Bhopal: Madhya Pradesh Hindi Granth. Course - 102 (General Theory) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To study Aesthetics in Music. 2. To appreciate the aesthetic aspects of different forms of music. Course Content:- I. Definition of Aesthetics and its Application in Music. II. Aesthetical principles of Different Haran’s. III. Aesthetical aspects of different forms of Music. a. Dhrupad, Dhamar, Khayal, Thumri, Tappa etc. IV. Merits and demerits of vocalist. Bibliographies:- a. Bosanquet, B. (2001). The concept of Aesthetics. New Delhi: Sethi Publishing Company. b. Dr. Bahulkar, S. Kalashastra Visharad (Vol. -

Rakti in Raga and Laya

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS Sangita Kalanidhi R. Vedavalli is not only one of the most accomplished of our vocalists, she is also among the foremost thinkers of Carnatic music today with a mind as insightful and uncluttered as her music. Sruti is delighted to share her thoughts on a variety of topics with its readers. Rakti in raga and laya Rakti in raga and laya’ is a swara-oriented as against gamaka- complex theme which covers a oriented raga-s. There is a section variety of aspects. Attempts have of exponents which fears that ‘been made to interpret rakti in the tradition of gamaka-oriented different ways. The origin of the singing is giving way to swara- word ‘rakti’ is hard to trace, but the oriented renditions. term is used commonly to denote a manner of singing that is of a Yo asau Dhwaniviseshastu highly appreciated quality. It swaravamavibhooshitaha carries with it a sense of intense ranjako janachittaanaam involvement or engagement. Rakti Sankarabharanam or Bhairavi? rasa raga udaahritaha is derived from the root word Tyagaraja did not compose these ‘ranj’ – ranjayati iti ragaha, ranjayati kriti-s as a cluster under the There is a reference to ‘dhwani- iti raktihi. That which is pleasing, category of ghana raga-s. Older visesha’ in this sloka from Brihaddcsi. which engages the mind joyfully texts record these five songs merely Scholars have suggested that may be called rakti. The term rakti dhwanivisesha may be taken th as Tyagaraja’ s compositions and is not found in pre-17 century not as the Pancharatna kriti-s. Not to connote sruti and that its texts like Niruktam, Vyjayanti and only are these raga-s unsuitable for integration with music ensures a Amarakosam. -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

Sripadaraja Mutt Address

Sripadaraja Mutt Address Head Office : Sri Sripadaraja Mutt (Mulbagal Mutt) Sri Narasimha Theertha, Mulbagal - 563 131, Karnataka, India Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 (Resi) (08159) 542686 Mulbagilu Branch - Mulbagal Town Mutt Sri Sripadaraja Pratistitha Sri Lakshminarayana and Sri Vysaraja Pratistitha 1st Hanuman Statue Mulbagal - 563131 Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 Nangli branch Sri Srikantha Theertha Brindavana, Nangli Village Mulbagal Taluk Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 Bangalore Branch 58, Raghavendra Colony, Chamrajpet Bangalore - 560 018 Contact:- Sri. S R Sreedharachar Ph:(080)266730232 Bangalore-Rajaji Nagar Branch # 542/31, 63rd Cross, Rajajainagar Near Bhasyam Circle Bangalore Contact:- Sri. Ravikiran Ph: 9880054620 Jigani Branch Sri Raghavendra Swamy Brindavan Near Busstand, Jigani Anekall Taluk Bangalore - 562 106 Contact:- Sri. Prakash & Sri Giriachar Ph: (080) 7826317 99010 975671 Mysore Branch Sri Sripadaraja Mutt (Sri Devendra Theertha Mutt) Ramanujam Road Mysore - 570 001 Source : Sripadaraja Mutt.org Collection by Narahari Sumadhwa Page 1 Sripadaraja Mutt Address Srirangapatna Branch Sri Gnananidhigala Brindavana, Water Gate, Srirangapatna - 571 438 Contact:- Sri. Jayasimhachar, & Sri Ananda Theetha Ph: (08326) 253540 (08326) 252340 Yeragambali Branch Sri Raghunatha Theerhtara Brindavana Yeragampally Yelandur Taluk Contact :- Sri. Bala Krishna achar (08221) 223924 Thayuru Branch Sri Gunanidhi Theertha Brindavan Kapila River Thayuru Contact :- Sri. Bala Krishna Achar (08221) 223924 Udupi Branch Car Street Udupi ANDRA PRADESH BRANCHES – Penugonda Branch Sri Sripadarja Prathisthitha Hanumal Temple Old Post Office Street Penukonda Contact:- Sri. Ananta Rao Ph: (08555) 221090 Sri Uddanda Ramachandra Theertha Brindavan Bangalore - Hyderabad Highway Penukonda Contact:- Sri. Ananta Rao Ph: (08555) 221090 Punganur Branch Brahmin Street Punganur Contact:- Sri. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

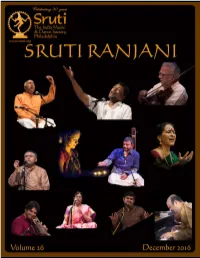

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

Tillana Raaga: Bageshri; Taala: Aadi; Composer

Tillana Raaga: Bageshri; Taala: Aadi; Composer: Lalgudi G. Jayaraman Aarohana: Sa Ga2 Ma1 Dha2 Ni2 Sa Avarohana: Sa Ni2 Dha2 Ma1 Pa Dha2 Ga2 Ma1 Ga2 Ri2 Sa SaNiDhaMa .MaPaDha | Ga. .Ma | RiRiSa . || DhaNiSaGa .SaGaMa | Dha. MaDha| NiRi Sa . || DhaNiSaMa .GaRiSa |Ri. NiDha | NiRi Sa . || SaRiNiDha .MaPaDha |Ga . Ma . | RiNiSa . || Sa ..Ni .Dha Ma . |Sa..Ma .Ga | RiNiSa . || Sa ..Ni .Dha Ma~~ . |Sa..Ma .Ga | RiNiSa . || Pallavi tom dhru dhru dheem tadara | tadheem dheem ta na || dhim . dhira | na dhira na Dhridhru| (dhirana: DhaMaNi .. dhirana.: DhaMaGa .) tom dhru dhru dheem tadara | tadheem dheem ta na || dhim . dhira | na dhira na Dhridhru|| (dhirana: MaDha NiSa.. dhirana:DhaMa Ga..) tom dhru dhru dheem tadara | tadheem dheem ta na || (ta:DhaNi na:NiGaRi) dhim . dhira | na dhira na Dhridhru|| (dhirana:NiGaSaSaNi. Dhirana:DhaSaNiNiDha .) tom dhru dhru dheem tadara | tadheem dheem ta na || dhim . dhira | na dhira na Dhridhru|| (dhira:GaMaDhaNi na:GaGaRiSa dhira:NiDha na:Ga..) tom dhru dhru dheem tadana | tadheem dheem ta na || dhim.... Anupallavi SaMa .Ga MaNi . Dha| NiGa .Ri | NiDhaSa . || GaRi .Sa NiMa .Pa | Dha Ga..Ma | RiNi Sa . || naadhru daani tomdhru dhim | ^ta- ka-jha | Nuta dhim || … naadhru daani tomdhru dhim | (Naadru:MaGa, daani:DhaMa, tomdhru:NiDha, dhim: Sa) ^ta- ka-jha | Nuta dhim || (NiDha SaNi RiSa) taJha-Nu~ta dhim jhaNu | (tajha:SaSa Nu~ta: NiSaRiSa dhim:Ni; jha~Nu:MaDhaNi. tadhim . na | ta dhim ta || (tadhim:Dha Ga..;nata dhimta: MNiDha Sa.Sa) tanadheem .tatana dheemta tanadheem |(tanadheemta: DhaNi Ri ..Sa tanadheem: NiRiSa. .Sa tanadheem: NiDhaNi . ) .dheem dheemta | tom dhru dheem (dheem: Sa deemta:Ga.Ma tomdhrudeem:Ri..Ri Sa) .dheem dheem dheemta ton-| (dheem:Dha. -

Divya Dvaita Drishti

Divya Dvaita Drishti PREETOSTU KRISHNA PR ABHUH Volume 1, Issue 4 November 2016 Madhva Drishti The super soul (God) and the individual soul (jeevatma) reside in the Special Days of interest same body. But they are inherently of different nature. Diametrically OCT 27 DWADASH - opposite nature. The individual soul has attachment over the body AKASHA DEEPA The God, in spite of residing in the same body along with the soul has no attach- OCT 28 TRAYODASHI JALA POORANA ment whatsoever with the body. But he causes the individual soul to develop at- tachment by virtue of his karmas - Madhvacharya OCT 29 NARAKA CHATURDASHI OCT 30 DEEPAVALI tamasOmA jyOtirgamaya OCT 31 BALI PUJA We find many happy celebrations in this period of confluence of ashwija and kartika months. NOV 11 KARTIKA EKA- The festival of lights dipavali includes a series of celebrations for a week or more - Govatsa DASHI Dvadashi, Dhana Trayodashi, Taila abhyanjana, Naraka Chaturdashi, Lakshmi Puja on NOV 12 UTTHANA Amavasya, Bali Pratipada, Yama Dvititya and Bhagini Tritiya. All these are thoroughly en- DWADASHI - TULASI joyed by us. Different parts of the country celebrate these days in one way or another. The PUJA main events are the killing of Narakasura by Sri Krishna along with Satyabhama, restraining of Bali & Lakshmi Puja on amavasya. Cleaning the home with broom at night is prohibited on other days, but on amavasya it is mandatory to do so before Lakshmi Puja. and is called alakshmi nissarana. Next comes completion of chaturmasa and tulasi puja. We should try to develop a sense of looking for the glory of Lord during all these festivities. -

Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men

Volume 64, Issue 1, 2020 Journal of Scientific Research Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men Samarpita Chatterjee (Mukherjee) 1, and Roan Mukherjee2* 1 Department of Hindustani Classical Music (Vocal), Sangit-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati (A Central University), Santiniketan, Birbhum-731235,West Bengal, India 2 Department of Human Physiology, Hazaribag College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Demotand, Hazaribag 825301, Jharkhand, India. [email protected] Abstract Several studies have indicated that music therapy may affect I. INTRODUCTION cardiovascular health; in particular, it may bring positive changes Music may be regarded as the projection of ideas as well as in blood pressure levels and heart rate, thereby improving the emotions through significant sounds produced by an instrument, overall quality of life. Hence, to regulate blood pressure, music voices, or both by taking into consideration different elements of therapy may be regarded as a significant complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The respiratory rate, if maintained melody, rhythm, and harmony. Music plays an important role in within the normal range, may promote good cardiac health. The everyone’s life. Music has the power to make one experience aim of the present study was to evaluate the changes in blood harmony, emotional ecstasy, spiritual uplifting, positive pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate in healthy and disease-free behavioral changes, and absolute tranquility. The annoyance in males (age 50-60 years), at the completion of 30 days of music life may increase in lack of melody and harmony.