Sendai Virus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extracting Structured Genotype Information from Free-Text HLA

J Korean Med Sci. 2020 Mar 30;35(12):e78 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e78 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Original Article Extracting Structured Genotype Medical Informatics Information from Free-Text HLA Reports Using a Rule-Based Approach Kye Hwa Lee ,1 Hyo Jung Kim ,2 Yi-Jun Kim ,1 Ju Han Kim ,2 and Eun Young Song 3 1Center for Precision Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea 2Division of Biomedical Informatics, Seoul National University Biomedical Informatics and Systems Biomedical Informatics Research Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: May 16, 2019 ABSTRACT Accepted: Jan 29, 2020 Address for Correspondence: Background: Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing is important for transplant patients to Eun Young Song, MD, PhD prevent a severe mismatch reaction, and the result can also support the diagnosis of various Division of Biomedical Informatics, Seoul disease or prediction of drug side effects. However, such secondary applications of HLA National University Biomedical Informatics (SNUBI) and Systems Biomedical Informatics typing results are limited because they are typically provided in free-text format or PDFs on Research Center, Seoul National University electronic medical records. We here propose a method to convert HLA genotype information College of Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, stored in an unstructured format into a reusable structured format by extracting serotype/ Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea. allele information. E-mail: [email protected] Methods: We queried HLA typing reports from the clinical data warehouse of Seoul National Kye Hwa Lee, MD, PhD University Hospital (SUPPREME) from 2000 to 2018 as a rule-development data set (64,024 Center for Precision Medicine, Seoul National reports) and from the most recent year (6,181 reports) as a test set. -

Cluster-Specific Gene Markers Enhance Shigella and Enteroinvasive Escherichia Coli in Silico Serotyping Xiaomei Zhang1, Michael

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.30.428723; this version posted February 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Cluster-specific gene markers enhance Shigella and Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli in 2 silico serotyping 3 4 Xiaomei Zhang1, Michael Payne1, Thanh Nguyen1, Sandeep Kaur1, Ruiting Lan1* 5 6 1School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 7 New South Wales, Australia 8 9 10 11 *Corresponding Author 12 Email: [email protected] 13 Phone: 61-2-9385 2095 14 Fax: 61-2-9385 1483 15 16 Keywords: Phylogenetic clusters, cluster-specific gene markers, Shigella/EIEC serotyping 17 Running title: Shigella EIEC Cluster Enhanced Serotyping 18 Repositories: Raw sequence data are available from NCBI under the BioProject number 19 PRJNA692536. 20 21 22 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.30.428723; this version posted February 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 23 Abstract 24 Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) cause human bacillary dysentery with 25 similar invasion mechanisms and share similar physiological, biochemical and genetic 26 characteristics. The ability to differentiate Shigella and EIEC from each other is important for 27 clinical diagnostic and epidemiologic investigations. The existing genetic signatures may not 28 discriminate between Shigella and EIEC. However, phylogenetically, Shigella and EIEC 29 strains are composed of multiple clusters and are different forms of E. -

For Reprint Orders, Please Contact: Reprints@ Futuremedicine

Research Article For reprint orders, please contact: [email protected] Association of the HLA-B alleles with carbamazepine-induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in the Javanese and Sundanese population of Indonesia: the important role of the HLA-B75 serotype Rika Yuliwulandari*,1,2,3, Erna Kristin3,4, Kinasih Prayuni2, Qomariyah Sachrowardi5, Franciscus D Suyatna3,6, Sri Linuwih Menaldi7, Nuanjun Wichukchinda8, Surakameth Mahasirimongkol8 & Larisa H Cavallari9 1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, YARSI University, Cempaka Putih, Jakarta Pusat, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 2Genomic Medicine Research Centre, YARSI Research Institute, YARSI University, Cempaka Putih, Jakarta Pusat, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 3The Indonesian Pharmacogenomics Working Group, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 4Department of Pharmacology & Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 5Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, YARSI University, Cempaka Putih, Jakarta Pusat, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 6Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutic, Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia, Salemba, Jakarta Pusat, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 7Department of Dermatology Clinic, Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia, Salemba, Jakarta Pusat, DKI Jakarta, Indonesia 8Medical Genetics Center, Medical Life Sciences Institute, Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand 9College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32603, USA * Author for correspondence: Tel.: +62 21 4206675; Fax: +62 21 4243171; [email protected] Carbamazepine (CBZ) is a common cause of life-threatening cutaneous adverse drug reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Previous studies have reported a strong association between the HLA genotype and CBZ-induced SJS/TEN. We investigated the association between the HLA genotype and CBZ-induced SJS/TEN in Javanese and Sundanese patients in Indonesia. -

Association of an HLA-DQ Allele with Clinical Tuberculosis

Brief Report Association of an HLA-DQ Allele With Clinical Tuberculosis Anne E. Goldfeld, MD; Julio C. Delgado, MD; Sok Thim; M. Viviana Bozon, MD; Adele M. Uglialoro; David Turbay, MD; Carol Cohen; Edmond J. Yunis, MD Context.—Although tuberculosis (TB) is the leading worldwide cause of death clinical TB, we performed a 2-stage study due to an infectious disease, the extent to which progressive clinical disease is as- of molecular typing of HLA class I and sociated with genetic host factors remains undefined. class II alleles and also tested for the pres- α Objective.—To determine the distribution of HLA antigens and the frequency of ence of 2 TNF- alleles in Cambodian pa- 2 alleles of the tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a) gene in unrelated individuals with tients with clinical TB and in control indi- viduals who did not have a history of TB. clinical TB (cases) compared with individuals with no history of clinical TB (controls) in a population with a high prevalence of TB exposure. Methods Design.—A 2-stage, case-control molecular typing study conducted in 1995-1996. The study subjects were unrelated Cam- Setting.—Three district hospitals in Svay Rieng Province in rural Cambodia. bodian patients recruited from a TB treat- Patients.—A total of 78 patients with clinical TB and 49 controls were included ment program in eastern rural Cambodia. in the first stage and 48 patients with TB and 39 controls from the same area and Two different groups of patients and con- socioeconomic status were included in the second stage. -

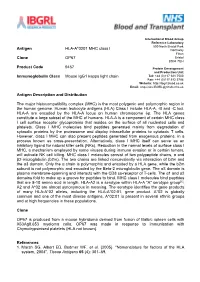

Antigen HLA-A*0201 MHC Class I Clone OP67 Product Code 9467

International Blood Group Reference Laboratory 500 North Bristol Park Antigen HLA-A*0201 MHC class I Northway Filton Clone OP67 Bristol BS34 7QH Product Code 9467 Protein Development and Production Unit Immunoglobulin Class Mouse IgG1 kappa light chain Tel: +44 (0)117 921 7500 Fax: +44 (0)117 912 5796 Website: http://ibgrl.blood.co.uk Email: [email protected] Antigen Description and Distribution The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is the most polygenic and polymorphic region in the human genome. Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) Class I include HLA-A, -B and -C loci. HLA-A are encoded by the HLA-A locus on human chromosome 6p. The HLA genes constitute a large subset of the MHC of humans. HLA-A is a component of certain MHC class I cell surface receptor glycoproteins that resides on the surface of all nucleated cells and platelets. Class I MHC molecules bind peptides generated mainly from degradation of cytosolic proteins by the proteasome and display intracellular proteins to cytotoxic T cells. However, class I MHC can also present peptides generated from exogenous proteins, in a process known as cross-presentation. Alternatively, class I MHC itself can serve as an inhibitory ligand for natural killer cells (NKs). Reduction in the normal levels of surface class I MHC, a mechanism employed by some viruses during immune evasion or in certain tumors, will activate NK cell killing. MHC class I molecules consist of two polypeptide chains, α and β2-microglobulin (b2m). The two chains are linked noncovalently via interaction of b2m and the α3 domain. -

Accepted Version

Article The cellular protein TIP47 restricts Respirovirus multiplication leading to decreased virus particle production BAMPI, Carole, et al. Abstract The cellular tail-interacting 47-kDa protein (TIP47) acts positively on HIV-1 and vaccinia virus production. We show here that TIP47, in contrast, acts as a restriction factor for Sendai virus production. This conclusion is supported by the occurrence of increased or decreased virus production upon its suppression or overexpression, respectively. Pulse-chase metabolic labeling of viral proteins under conditions of TIP47 suppression reveals an increased rate of viral protein synthesis followed by increased incorporation of viral proteins into virus particles. TIP47 is here described for the first time as a viral restriction factor that acts by limiting viral protein synthesis. Reference BAMPI, Carole, et al. The cellular protein TIP47 restricts Respirovirus multiplication leading to decreased virus particle production. Virus Research, 2013, vol. 173, no. 2, p. 354-63 DOI : 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.01.006 PMID : 23348195 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:28890 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Virus Research 173 (2013) 354–363 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Virus Research journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/virusres The cellular protein TIP47 restricts Respirovirus multiplication leading to decreased virus particle production a a,b,1 c,d Carole Bampi , Anne-Sophie Gosselin Grenet , Grégory Caignard -

Introduction to the Peptide Binding Problem of Computational Immunology: New Results

Found Comput Math DOI 10.1007/s10208-013-9173-9 Introduction to the Peptide Binding Problem of Computational Immunology: New Results Wen-Jun Shen · Hau-San Wong · Quan-Wu Xiao · Xin Guo · Stephen Smale Received: 26 August 2012 / Revised: 5 May 2013 / Accepted: 17 July 2013 © SFoCM 2013 Abstract We attempt to establish geometrical methods for amino acid sequences. To measure the similarities of these sequences, a kernel on strings is defined using only the sequence structure and a good amino acid substitution matrix (e.g. BLOSUM62). The kernel is used in learning machines to predict binding affinities of peptides to human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) molecules. On both fixed allele (Nielsen and Lund in BMC Bioinform. 10:296, 2009) and pan-allele (Nielsen et al. in Immunome Res. 6(1):9, 2010) benchmark databases, our algorithm achieves the state-of-the-art performance. The kernel is also used to define a distance on an HLA-DR allele set Communicated by Teresa Krick. W.-J. Shen · H.-S. Wong Department of Computer Science, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong W.-J. Shen e-mail: [email protected] H.-S. Wong e-mail: [email protected] Q.-W. Xiao Microsoft Search Technology Center Asia, Beijing, China e-mail: [email protected] X. Guo Department of Statistical Science, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA e-mail: [email protected] S. Smale (B) Department of Mathematics, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong e-mail: [email protected] Found Comput Math based on which a clustering analysis precisely recovers the serotype classifications assigned by WHO (Holdsworth et al. -

Improving Vaccines Against Streptococcus Pneumoniae Using Synthetic Glycans

Improving vaccines against Streptococcus pneumoniae using synthetic glycans Paulina Kaploneka,b,1, Naeem Khana,1, Katrin Reppec,d, Benjamin Schumanna,2, Madhu Emmadia,3, Marilda P. Lisboaa,3, Fei-Fei Xua, Adam D. J. Calowa, Sharavathi G. Parameswarappaa,3, Martin Witzenrathc,d, Claney L. Pereiraa,3, and Peter H. Seebergera,b,4 aDepartment of Biomolecular Systems, Max-Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, 14476 Potsdam, Germany; bInstitute of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Freie Universität Berlin, 14195 Berlin, Germany; cDivision of Pulmonary Inflammation, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Berlin Institute of Health, 10117 Berlin, Germany; and dDepartment of Infectious Diseases and Respiratory Medicine, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Berlin Institute of Health, 10117 Berlin, Germany Edited by Michael L. Klein, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, and approved November 6, 2018 (received for review July 11, 2018) Streptococcus pneumoniae remains a deadly disease in small chil- The procurement of polysaccharides for conjugate-vaccine dren and the elderly even though conjugate and polysaccharide production by the isolation of CPS from cultured bacteria is vaccines based on isolated capsular polysaccharides (CPS) are suc- conceptionally simple but operationally challenging. Antigen cessful. The most common serotypes that cause infection are used heterogeneity, batch-to-batch -

An Increase in Streptococcus Pneumoniae Serotype 12F

An Increase in Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 12F [Announcer] This program is presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Sarah Gregory] I’m talking today with Dr. Cynthia Whitney, a medical epidemiologist at CDC, about pneumonia vaccines and Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F. Welcome, Dr. Whitney. [Cynthia Whitney] Hello, it’s great to be here. [Sarah Gregory] After the PCV vaccine was introduced in Israel in 2009, there was apparently an increase in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 12F. Would tell us about this? [Cynthia Whitney] Sure. First let me tell you a little about pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and pneumococcal disease. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a bacteria that is also known as pneumococcus. This bacteria typically just lives happily in our noses and throats and doesn’t bother us. Occasionally, if a person catches a virus or their health is off in some other way, pneumococcus can grow and spread and cause disease. The main diseases pneumococcus causes are mild infections, like ear and sinus infections, but pneumococcus can also cause severe illnesses like pneumonia and meningitis. When you add up all these infections, pneumococcal disease is a leading cause of infections and deaths around the world, especially in infants and the elderly. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines are relatively new type of vaccine that has been shown to be highly effective at preventing disease and in stopping people from acquiring the bacteria in their noses and throats. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines are now used in infant vaccination programs in most countries around the world. The U.S. and a small number of other countries also use them in some adults. -

Human Leukocyte Antigen Susceptibility Map for SARS-Cov-2

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040600; this version posted March 26, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . TITLE Human leukocyte antigen susceptibility map for SARS-CoV-2 AUTHORS Austin Nguyen (1, 2), Julianne K. David (1, 2), Sean K. Maden (1, 2), Mary A. Wood (1, 3), Benjamin R. Weeder (1, 2), Abhinav Nellore* (1, 2, 4), Reid F. Thompson* (1, 2, 5, 6, 7) AFFILIATIONS 1. Computational Biology Program; Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 2. Department of Biomedical Engineering; Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 3. Portland VA Research Foundation; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 4. Department of Surgery; Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 5. Department of Radiation Medicine; Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 6. Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology; Oregon Health & Science University; Portland, OR, 97239; USA 7. Division of Hospital and Specialty Medicine; VA Portland Healthcare System; Portland, OR, 97239; USA * co-corresponding authors [[email protected], [email protected]] NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20040600; this version posted March 26, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Evidence of HLA-DQB1 Contribution to Susceptibility of Dengue Serotype 3 in Dengue Patients in Southern Brazil

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Tropical Medicine Volume 2014, Article ID 968262, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/968262 Research Article Evidence of HLA-DQB1 Contribution to Susceptibility of Dengue Serotype 3 in Dengue Patients in Southern Brazil Daniela Maria Cardozo, Ricardo Alberto Moliterno, Ana Maria Sell, Gláucia Andréia Soares Guelsin, Leticia Maria Beltrame, Samaia Laface Clementino, Pamela Guimarães Reis, Hugo Vicentin Alves, Priscila Saamara Mazini, and Jeane Eliete Laguila Visentainer Laboratorio´ de Imunogenetica,´ Departamento de Cienciasˆ Basicas´ da Saude,´ Universidade Estadual de Maringa,´ Av. Colombo 5790, 87020-900 Maringa,´ PR, Brazil Correspondence should be addressed to Jeane Eliete Laguila Visentainer; [email protected] Received 10 January 2014; Accepted 6 March 2014; Published 10 April 2014 Academic Editor: Sukla Biswas Copyright © 2014 Daniela Maria Cardozo et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Dengue infection (DI) transmitted by arthropod vectors is the viral disease with the highest incidence throughout the world, an estimated 300 million cases per year. In addition to environmental factors, genetic factors may also influence the manifestation of the disease; as even in endemic areas, only a small proportion of people develop the most serious form. Immune-response gene polymorphisms may be associated with the development of cases of DI. The aim of this study was to determine allele frequencies in the HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DQA1, and DQB1 loci in a Southern Brazil population with dengue virus serotype 3, confirmed by the ELISA serological method, and a control group. -

Antigen HLA-A*02:01 MHC Class I Clone OP67 Product Code

Antigen HLA-A*02:01 MHC class I Clone OP67 Product Code 9467 Immunoglobulin Class Mouse IgG1 kappa light chain Antigen Description and Distribution The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is the most polygenic and polymorphic region in the human genome. Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) Class I include HLA-A, -B and -C loci. HLA-A are encoded by the HLA-A locus on human chromosome 6p. The HLA genes constitute a large subset of the MHC of humans. HLA-A is a component of certain MHC class I cell surface receptor glycoproteins that resides on the surface of all nucleated cells and platelets. Class I MHC molecules bind peptides generated mainly from degradation of cytosolic proteins by the proteasome and display intracellular proteins to cytotoxic T cells. However, class I MHC can also present peptides generated from exogenous proteins, in a process known as cross-presentation. Alternatively, class I MHC itself can serve as an inhibitory ligand for natural killer cells (NKs). Reduction in the normal levels of surface class I MHC, a mechanism employed by some viruses during immune evasion or in certain tumors, will activate NK cell killing. MHC class I molecules consist of two polypeptide chains, and 2-microglobulin (b2m). The two chains are linked noncovalently via interaction of b2m and the 3 domain. Only the chain is polymorphic and encoded by a HLA gene, while the b2m subunit is not polymorphic and encoded by the Beta-2 microglobulin gene. The 3 domain is plasma membrane-spanning and interacts with the CD8 co-receptor of T-cells.