Iain Dickson's Msc Dissertation – November 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flitwick, Ampthill and Cranfield Bus Timetable 6 Meppersha Meppersha 79.89 Moggerhan a X 61.321 W1 X Biggleswade Y Luton Airport W2

Lavendon Oakley A421 G rea Stevington t O Clapham 0 us 6 e 6 Renhold B Salph B565 1A End Turvey Gre A4 Bedford Great 112X at Ou 28 se 1A Bus Station Bedford Barford Cold Corn Exchange I5X 1A.1C.M1.S1.V1.J2 Bedford Bedford For further details in the Bedford area, Brayfield X I6X M2.V2X.M3.M4 River Street Horne Lane W1X.W2X please see separate publicity I7 1A X 1C R2X produced by Bedford Borough Council I6X I7 1A Bromham 42.44.160X.165X I5X R3X F5X.F8X X5 I5X I7X I6X A I5X er & Newton 6 Goldington X5 Museum X5 se I5X A4 1 Ou 2 A428 2 Great 8 Bedford 4 Willington 22 Biddenham I5X A Willington 4 X5 Riverfield Road Dovecote A X5 1A Queen’s Park Bedford Museum Tesco ton 1C Station Cardington Road R2X 1C I6X.I7X M3 I5X M3 Kempston Tesco 1C Great Williamson Court F8X Stagsden Denham A603 X5 R1X.R2X Box 3 M3X Moggerhang R2X A60 End Cople A V1 X A I5X 5 V2 4444 6 M4 1 0 X 3 RR22X 4422 0 M3 4 KKempstonempston FF55X S1 R3R3X Astwood J2J2 Cardington M4 F8X S1 M1.M2X.M3 M1 Wood End R1X 30 44 M2 R2X 5 M4.W1X.W2X Gibraltar B W1X 422 R2X 160X 1A A 165X W2X F8X 1 Elstow X5 Wood End V1V2X A42 1C R2X R1X.R2X Shortstown Chicheley V1 JJ22 RR33•X 4422 V2X R2X Hall End V2X A Cotton V1X Chicheley 6 Wootton FF55X End Hall North S1 J2 44 Biggleswade Crawley X A FF88 6 V2X 0 PLUSBUS Zone 1A Bourne 4422 0 1 End KKempstonempston Wixams X5 V1 HHardwickardwick SStationtation Old 1 R3X Upper M1 Warde 17 160X M2 Shelton R1X J2 17AX 165X W1X Cranfield V2X F5X University Wharley W2X Old W V2X R3X R1X 160X F8X End R3X X R1X R3X V1 R1X Stewartby 42 Wilstead V1.V2 V1 I1A A -

Chairman's Notes

NEWSLETTER Dunstable District Local History Society No. 58 June 2021 Chairman’s Notes elcome to another special Despite some bad weather Rita Swift, W‘lockdown’ newsletter: we David Underwood, John Stevens, Liz are producing some extra issues Bentley, Jenny Dilnot and my wife during the times of Covid so we were kept busy and raised £206 for can all try to keep in touch. society funds. We were visited by King Henry VIII (see photo) and we had to Most of this edition is devoted to explain to him the difference between the Manshead Archaeological Soci- a divorce and his marriage annulment ety, which has closed down after at Dunstable Priory. You would have many years at the forefront of exciting thought he would have known! discoveries about Dunstable’s past. We think it is important to publish Mans- ● If all goes well, the society will have head’s story and make it available to a a tent in Priory Gardens for Archae- worldwide readership via our website. ology Day on Saturday, July 24. ● We are hoping to resume our month- ● Your chairman has also had to ly meetings in September but nothing The History Society market stall on May 15th brave a Microsoft Teams meeting is certain and much depends on government advice and the feasibility of the council’s Community Services Committee to talk about the of using the Methodist church hall once more. society’s work. ● Meanwhile, we have held our annual meeting on Zoom, at which ● The society has manned a gazebo in Grove House Gardens as part the following committee was elected: chairman John Buckledee, of the council’s Queensway Hall of Fame event, for which we tried vice-chairman Hugh Garrod, treasurer Patricia Larkman, membership to assemble a list of all the rock bands who appeared at the hall. -

Area D Assessments

Central Bedfordshire Council www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk Appendix D: Area D Assessments Central Bedfordshire Council Local Plan Initial Settlements Capacity Study CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COUNCIL LOCAL PLAN: INITIAL SETTLEMENTS CAPACITY STUDY Appendix IID: Area D Initial Settlement Capacity Assessment Contents Table BLUNHAM .................................................................................................................. 1 CAMPTON ................................................................................................................. 6 CLIFTON ................................................................................................................... 10 CLOPHILL ................................................................................................................. 15 EVERTON .................................................................................................................. 20 FLITTON & GREENFIELD ............................................................................................ 24 UPPER GRAVENHURST ............................................................................................. 29 HAYNES ................................................................................................................... 33 LOWER STONDON ................................................................................................... 38 MAULDEN ................................................................................................................ 42 MEPPERSHALL ......................................................................................................... -

Central Bedfordshire Educational Planning Areas

Central Bedfordshire Council www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk Central Bedfordshire Educational Planning Areas Biggleswade / Sandy Rural Mid-Bedfordshire Leighton Buzzard / Linslade Dunstable / Houghton Regis Area 1 – Dunstable and Houghton Regis Nursery Westfield (C) Willow (C) Lower/Primary Beecroft (A); Eaton Bray (A) Caddington Village (C, T) St Christopher’s (A, T) Lancot (A, T); Tottenhoe (A,T ) Slip End (C,T) Hadrian (A) Hawthorn Park (C) St Augustine’s (A) Ardley Hill (A) Houghton Regis (C) Kensworth (CE,A T) Dunstable Icknield (C) Tithe Farm (C) Studham (CE VC) Larkrise (A)Watling (C) Thornhill (C) Voluntary Aided (VA) School’s operating outside of catchments: Ashton St Peters (CE VA), St Mary's (Cadd) (RC VA), St Vincent’s (RC A), Thomas Whitehead (A, T) Middle (deemed Secondary) The Vale (A, T) Priory (A) Secondary All Saints Academy (A,T) Manshead (A, T) Queensbury (A,T) Houghton Regis Academy (A, T) The Academy of Central Bedfordshire (A, dual school Site 1) Special The Chiltern (C) Weatherfield (A) Total: Nursery 2, Lower/Primary 23, Middle (deemed Sec) 2, Upper 5, Special 2 – total 34 Key: (C) – Community School, CE/RC VC – Voluntary Controlled, A – Academy (non LA maintained), Fed – Member of Federation, CE/RC VA – Voluntary Aided, F – Foundation, T – Trust February 2019 Central Bedfordshire Educational Planning Areas Biggleswade / Sandy Rural Mid-Bedfordshire Leighton Buzzard / Linslade Dunstable / Houghton Regis Area 2 – Leighton Buzzard and Linslade Lower/Primary The Mary Bassett (C); Stanbridge (C) Clipstone Brook (C); -

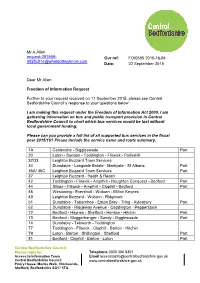

Dear Mr Allen Freedom of Information Request Further to Your Request

Mr A Allen request-291569- Our ref: FOI0595 2015-16JM [email protected] Date: 22 September 2015 Dear Mr Allen Freedom of Information Request Further to your request received on 11 September 2015, please see Central Bedfordshire Council’s response to your questions below: I am making this request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I am gathering information on bus and public transport provision in Central Bedfordshire Council to chart which bus services would be lost without local government funding. Please can you provide a full list of all supported bus services in the fiscal year 2015/16? Please include the service name and route summary. 1A Caldecotte - Biggleswade Part 20 Luton - Sundon - Toddington - Flitwick - Pulloxhill 32/33 Leighton Buzzard Town Services 34 Dunstable - Langdale Estate - Markyate - St Albans Part 36A/ 36C Leighton Buzzard Town Services Part 37 Leighton Buzzard - Heath & Reach 42 Toddington - Flitwick - Ampthill - Houghton Conquest - Bedford Part 44 Silsoe - Flitwick - Ampthill - Clophill - Bedford Part 48 Westoning - Eversholt - Woburn - Milton Keynes 49 Leighton Buzzard - Woburn - Ridgmont 61 Dunstable - Totternhoe - Eaton Bray - Tring - Aylesbury Part 62 Dunstable - Ridgeway Avenue - Caddington - Pepperstock 72 Bedford - Haynes - Shefford - Henlow - Hitchin Part 73 Bedford - Moggerhanger - Sandy - Biggleswade Part 74 Dunstable - Tebworth - Toddington 77 Toddington - Flitwick - Clophill - Barton - Hitchin 79 Luton - Barton - Shillington - Shefford Part 81 Bedford - Clophill - Barton - Luton -

Allocated School by Pupil Catchment - Area 4 - Rural Mid-Bedfordshire (Ampthill, Flitwick, Cranfield, Stotfold & Shefford - Lower/Primary

School Listing - Allocated School by Pupil Catchment - Area 4 - Rural Mid-Bedfordshire (Ampthill, Flitwick, Cranfield, Stotfold & Shefford - Lower/Primary Allocated School Total All Saints Lower School Campton Lower School Chalton Lower School Church End Lower School Cranfield C of E Academy Derwent Lower School Eversholt Lower School Fairfield Park Lower School Flitwick Lower School Gothic Mede Lower School Gravenhurst Lower School Greenfield C Of E V.C Lower School Harlington Lower School Haynes Lower School Houghton Conquest Lower School Kingsmoor Lower School Langford Lower School Maulden Lower School Meppershall Lower School Pulloxhill Lower Ramsey Manor Lower School Raynsford V.C Lower School Roecroft School Russell Lower School Shefford Lower School Shelton Lower School Shillington Lower School Silsoe V.C Lower School Southill Lower School St Mary's C Of E Academy, Stotfold St Mary's C Of E Lower School (clophill) Stondon Lower School Sundon Lower School Templefield Lower School The Firs Lower School Thomas Johnson Lower School Toddington St George V.C. Lower School Westoning Lower School All Saints 39 31 2 3 1 2 Lower Aspley Guise 1 1 Beecroft 1 1 Caldecote 1 1 Campton 35 28 1 3 3 Chalton 7 2 5 Church End 53 49 1 3 Cranfield 47 46 1 Catchment Area Derwent 33 24 1 1 7 Downside 2 1 1 Eversholt 10 9 1 Fairfield Park 73 73 Flitwick 30 20 1 8 1 Gothic Mede 76 68 1 4 3 Total All Saints Lower School Campton Lower School Chalton Lower School Church End Lower School Cranfield C of E Academy Derwent Lower School Eversholt Lower School Fairfield -

Eversholt Parish Council

EVERSHOLT PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES of the Meeting of Eversholt Parish Council held on Tuesday 29th January 2019 at 7.30pm in the Village Hall, Eversholt PRESENT: Cllrs Mrs M Gabrys (Chairman), Mrs C Birch, Mr A Miller, Mrs F Newport-Hassan, Mr P Richardson, CBC Cllr Mr B Wells IN ATTENDANCE: Mrs K Barker (Clerk), 18 members of the public were present 1232 Apologies for absence – Cllr Mr W Creamer 1233 Declaration of interests – Cllr Richardson – Village Hall, Eversholt Parochial Charity, Cllr Miller – Swimming Pool 1234 Minutes The minutes of the meetings held on 27th November and 11th December 2018 were approved. Cllr Richardson proposed, seconded by Cllr Birch the approval of the minutes as a true record. All agreed by those present and signed by the Chairman. 1235 Cllr Robin Smith Cllrs spoke of the sad loss of Cllr Robin Smith who passed away in December. He was a very active member of the Parish Council for many years and the Parish Council would like to express their thanks for all the good work he did and his dedication to the Village. He will be very sadly missed. Cllr Richardson said that a tribute will need to be agreed to commemorate Robin’s life and commitment to the village and the Parish Council, Village Hall Committee and the Parochial Charity will need to discuss this. 1236 Matters Arising There were no matters arising. 1237 Reports and representations 1237.1 Central Beds Councillor Wells Cllr Wells said that the CBC budget consultation has now ended. A good response has been received and the results will be analysed shortly. -

Aspley Guise Cricket Club Junior Fixtures 2020 Bedfordshire Youth

Aspley Guise Cricket Club Junior Fixtures 2020 Bedfordshire Youth Cricket League U15 Development South (18:00 on Thursdays) Teams 30 April 2020 Aspley Guise v Flitwick Aspley Guise 07 May 2020 Lutonian v Aspley Guise Flitwick 14 May 2020 Aspley Guise v Studham Lutonian 21 May 2020 Aspley Guise v Lutonian Luton Caribbean 28 May 2020 Luton Caribbean v Aspley Guise Studham 04 June 2020 Studham v Aspley Guise 11 June 2020 Flitwick v Aspley Guise 25 June 2020 Lutonian v Aspley Guise 09 July 2020 Aspley Guise v Studham 16 July 2020 Aspley Guise v Luton Caribbean 23 July 2020 Flitwick v Aspley Guise 30 July 2020 Aspley Guise v Luton Caribbean U13 Development South (18:00 on Tuesdays) Teams 05 May 2020 Eversholt v Aspley Guise Aspley Guise 12 May 2020 Aspley Guise v Ampthill Town Ampthill Town 19 May 2020 Eaton Bray B v Aspley Guise Eaton Bray 26 May 2020 Eaton Bray v Aspley Guise Eaton Bray B 09 June 2020 Aspley Guise v Flitwick Eversholt 16 June 2020 Aspley Guise v Eaton Bray B Flitwick 23 June 2020 Aspley Guise v Eversholt 07 July 2020 Ampthill Town v Aspley Guise 14 July 2020 Aspley Guise v Eaton Bray 21 July 2020 Flitwick v Aspley Guise Aspley Guise Cricket Club Junior Fixtures 2020 Bedfordshire Youth Cricket League U11 Development South (10:00 on Sundays) Teams 03 May 2020 Aspley Guise v Flitwick Aspley Guise 10 May 2020 Eversholt v Aspley Guise Ampthill Town 17 May 2020 Eaton Bray v Aspley Guise Dunstable Town 24 May 2020 Aspley Guise v Studham Eaton Bray 31 May 2020 Dunstable Town v Aspley Guise Eversholt 14 June 2020 Ampthill Town v Aspley -

In This Issue for the Enjoyment of Future Generations

BEDFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION HISTORY IN BEDFORDSHIRE VOLUME 6, NO 7 SPRING 2014 www.bedfordshire-lha.org.uk could be given to the nation and protected and preserved In this issue for the enjoyment of future generations. Notes and news: BLHA Annual Conference 2014 & AGM; Miss Caroline’s Campaign; Frank Sweetland She and Lyndon Bolton, then president of the Bedford Bedfordshire in 1670:evidence from the hearth tax, Pt 1: Arts Club, contacted their friends and acquaintances, wrote DOROTHY JAMIESON letters to the Board of Works (later English Heritage), the Book Reviews: T E D M A R T I N National Trust and local and national newspapers. As a result more than 80 people contributed and the amount Notes and news needed was raised in just over two months. The dovecote was purchased at the end of August 1912. BLHA Annual Conference Miss Orlebar found that giving the dovecote away was more difficult than she had anticipated and, sadly, she 2014 and AGM became ill and died before the transfer was completed. In HOSTED BY early 1914 her brother found that the Board of Works was MAULDEN HISTORY SOCIETY unable to accept the building, so he arranged for it to be transferred to the National Trust. AT The centenary of the handing over of the building to MAULDEN VILLAGE HALL the Trust will be celebrated at the Willington Dovecote and Flitwick Road, Maulden Stables during the summer. It is hoped that there will also Saturday, 14 June 2014 be a temporary display in the ‘Great Bedfordians’ gallery of Registration: 9.20 am AGM: 9.40–10.15 am the ‘Higgins’ in Bedford. -

The Old Rectory Steppingley | Bedfordshire

The Old Rectory Steppingley | Bedfordshire The Old Rectory Rectory Road | Steppingley | Bedfordshire | MK45 5AT A Grade II listed Georgian seven bedroom detached former rectory with a two bedroom detached cottage • Flitwick approx. 2 miles • Woburn approx. 4 miles • M1 junction 12 approx. 4 miles • Milton Keynes approx. 16 miles • Bedford approx. 15 miles • London approx. 44 miles Main House Ground Floor: Entrance Hall • Drawing Room • Dining Room • Family Room, • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Utility Room • Cloakroom First floor: Master Bedroom with En Suite Bath and Shower Room, • Three Further Bedrooms • Bathroom • WC Second Floor: Bedroom Five with Dressing Room and En Suite Bathroom • Two Further Bedrooms and Shower Room Lower Ground Floor: Cellar with Additional Chamber Detached Coach House Ground Floor: Entrance Hall • Sitting Room • Kitchen/Dining Room and WC First Floor: Two Bedrooms, both with En Suite Bathrooms Outbuilding • Double Garage Gardens & Grounds • Approximately 0.62 acres Total (Gross Internal Area) Main House: 5,798 sq. ft. (538.6 sq. m.) (excludes restricted head height and garage and includes coach house) History & heritage he Old Rectory displays a blend of architecture dating from the Georgian and Victorian eras. It is believed that the property was constructed Tin the early to mid 18th century and then extended soon after to the front, and latterly towards the end of the 18th century to the rear. The majority of the building comprises red brick with banding at first floor and cornice level, incorporating flush sash windows, under hipped clay tiled roofs. The property lies amongst properties of a similar age deriving from a programme of improvement implemented when the Duke of Bedford took up a greater ownership of the parish. -

1. Totternhoe Neighbourhood Plan (Referendum Version)

Totternhoe Neighbourhood Plan Referendum Version Totternhoe Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035 Totternhoe Parish Council Referendum Version Totternhoe Neighbourhood Plan Referendum Version Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 The Planning Policy Context ...................................................................................... 4 Community engagement .......................................................................................... 6 Sustainability of the Neighbourhood Plan .................................................................... 7 2 ABOUT TOTTERNHOE ................................................................................ 8 A brief history ........................................................................................................ 8 Population ............................................................................................................ 9 The parish today .................................................................................................... 9 3 VISION AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................................... 12 Challenges facing Totternhoe Parish ..........................................................................12 Vision for the Neighbourhood Plan ............................................................................12 Neighbourhood Plan Objectives ................................................................................12 4 SPATIAL STRATEGY -

140 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

140 bus time schedule & line map 140 Clophill - Flitwick - Eversholt - Filtwick - Clophill View In Website Mode The 140 bus line (Clophill - Flitwick - Eversholt - Filtwick - Clophill) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Clophill: 11:15 AM (2) Clophill: 9:00 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 140 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 140 bus arriving. Direction: Clophill 140 bus Time Schedule 66 stops Clophill Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Jacques Lane, Clophill Tuesday Not Operational St Mary's Church, Clophill Wednesday Not Operational The Green, Clophill Thursday Not Operational The Green, Clophill Civil Parish Friday Not Operational Pine View Park, Maulden Saturday 11:15 AM Water End Road, Maulden Green End, Maulden Redhills Close, Maulden 140 bus Info Direction: Clophill Maulden Lower School, Maulden Stops: 66 Trip Duration: 107 min The White Hart, Maulden Line Summary: Jacques Lane, Clophill, St Mary's Church, Clophill, The Green, Clophill, Pine View Park, Maulden, Water End Road, Maulden, Green End, The Brache, Maulden Maulden, Redhills Close, Maulden, Maulden Lower School, Maulden, The White Hart, Maulden, The Snow Hill, Maulden Brache, Maulden, Snow Hill, Maulden, Rectory Lane, Ampthill, Alameda Walk, Ampthill, Lavender Court, Rectory Lane, Ampthill Ampthill, Grange Road, Ampthill, Wagstaff Way, Ampthill, Wagstaff Way, Ampthill, 101 Garage, Alameda Walk, Ampthill Flitwick, Williams Way, Flitwick, The Ridgeway, Flitwick, Railway