CCC Guide to Understanding Ostomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OT Resource for K9 Overview of Surgical Procedures

OT Resource for K9 Overview of surgical procedures Prepared by: Hannah Woolley Stage Level 1 2 Gynecology/Oncology Surgeries Lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection) Surgical removal of lymph nodes Radical: most/all of the lymph nodes in tumour area are removed Regional: some of the lymph nodes in the tumour area are removed Omentectomy Surgical procedure to remove the omentum (thin abdominal tissue that encases the stomach, large intestine and other abdominal organs) Indications for omenectomy: Ovarian cancer Sometimes performed in combination with TAH/BSO Posterior Pelvic Exenteration Surgical removal of rectum, anus, portion of the large intestine, ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus (partial or total removal of the vagina may also be indicated) Indications for pelvic exenteration Gastrointestinal cancer (bowel, colon, rectal) Gynecological cancer (cervical, vaginal, ovarian, vulvar) Radical Cystectomy Surgical removal of the whole bladder and proximal lymph nodes In men, prostate gland is also removed In women, ovaries and uterus may also be removed Following surgery: Urostomy (directs urine through a stoma on the abdomen) Recto sigmoid pouch/Mainz II pouch (segment of the rectum and sigmoid colon used to provide anal urinary diversion) 3 Radical Vulvectomy Surgical removal of entire vulva (labia, clitoris, vestibule, introitus, urethral meatus, glands/ducts) and surrounding lymph nodes Indication for radical vulvectomy Treatment of vulvar cancer (most common) Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection (SLND) Exploratory procedure where the sentinel lymph node is removed and examined to determine if there is lymph node involvement in patients diagnosed with cancer (commonly breast cancer) Total abdominal hysterectomy/bilateral saplingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO) Surgical removal of the uterus (including cervix), both fallopian tubes and ovaries Indications for TAH/BSO: Uterine fibroids: benign growths in the muscle of the uterus Endometriosis: condition where uterine tissue grows on structures outside the uterus (i.e. -

Intestine Transplant Manual

Intestine Transplant Manual Toronto Intestine Transplant Program TRANSPLANT MANUAL E INTESTIN This manual is dedicated to our donors, our patients and their families Acknowledgements Dr. Mark Cattral, MD, (FRCSC) Dr. Yaron Avitzur, MD Andrea Norgate, RN, BScN Sonali Pendharkar, BA (Hons), BSW, MSW, RSW Anna Richardson, RD We acknowledge the contribution of previous members of the team and to Cheryl Beriault (RN, BScN) for creating this manual. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedications and Acknowledgements 2 Welcome 5 Our Values and Philosophy of Care Our Expectations of You Your Transplant Team 6 The Function of the Liver and Intestines 9 Where are the abdominal organs located and what do they look like? What does your Stomach do? What does your Intestine do? What does your Liver do? What does your Pancreas do? When Does a Patient Need an Intestine Transplant? 12 Classification of Intestine Failure Am I Eligible for an Intestine Transplant? Advantages and Disadvantages of Intestine Transplant The Transplant Assessment 14 Investigations Consultations Active Listing for Intestine Transplantation (Placement on the List) 15 Preparing for the Intestine Transplant Trillium Drug Program Other Sources of Funding for Drug Coverage Financial Planning Insurance Issues Other Financial Considerations Related to the Hospital Stay Legal Considerations for Transplant Patients Advance Care Planning Waiting for the Intestine Transplant 25 Your Place on the Waiting List Maintaining Contact with the Transplant Team Coping with Stress Maintaining your Health While -

Information for Patients Having a Sigmoid Colectomy

Patient information – Pre-operative Assessment Clinic Information for patients having a sigmoid colectomy This leaflet will explain what will happen when you come to the hospital for your operation. It is important that you understand what to expect and feel able to take an active role in your treatment. Your surgeon will have already discussed your treatment with you and will give advice about what to do when you get home. What is a sigmoid colectomy? This operation involves removing the sigmoid colon, which lies on the left side of your abdominal cavity (tummy). We would then normally join the remaining left colon to the top of the rectum (the ‘storage’ organ of the bowel). The lines on the attached diagram show the piece of bowel being removed. This operation is done with you asleep (general anaesthetic). The operation not only removes the bowel containing the tumour but also removes the draining lymph glands from this part of the bowel. This is sent to the pathologists who will then analyse each bit of the bowel and the lymph glands in detail under the microscope. This operation can often be completed in a ‘keyhole’ manner, which means less trauma to the abdominal muscles, as the biggest wound is the one to remove the bowel from the abdomen. Sometimes, this is not possible, in which case the same operation is done through a bigger incision in the abdominal wall – this is called an ‘open’ operation. It does take longer to recover with an open operation but, if it is necessary, it is the safest thing to do. -

Enteroliths in a Kock Continent Ileostomy: Case Report and Review of the Literature

E200 Cases and Techniques Library (CTL) similar symptoms recurred 2 years later. A second ileoscopy showed a narrowed Enteroliths in a Kock continent ileostomy: efferent loop that was dilated by insertion case report and review of the literature of the colonoscope, with successful relief of her symptoms. Chemical analysis of one of the retrieved enteroliths revealed calcium oxalate crystals. Five cases have previously been noted in the literature Fig. 1 Schematic (●" Table 1). representation of a Kock continent The alkaline milieu of succus entericus in ileostomy. the ileum may induce the precipitation of a calcium oxalate concretion; in contrast, the acidic milieu found more proximally in the intestine enhances the solubility of calcium. The gradual precipitation of un- conjugated bile salts, calcium oxalate, and Valve calcium carbonate crystals around a nidus composed of fecal material or undigested Efferent loop fiber can lead to the formation of calcium oxalate calculi over time [5]. Endoscopy_UCTN_Code_CCL_1AD_2AJ Reservoir Competing interests: None Hadi Moattar1, Jakob Begun1,2, Timothy Florin1,2 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Mater Adult Hospital, South Brisbane, Australia The Kock continent ileostomy (KCI) was dure was done to treat ulcerative pan- 2 Mater Research, University of Queens- designed by Nik Kock, who used an intus- colitis complicated by colon cancer. She land, Translational Research Institute, suscepted ileostomy loop to create a nip- had a well-functioning KCI that she had Woolloongabba, Australia ple valve (●" Fig.1) that would not leak catheterized daily for 34 years before she and would allow ileal effluent to be evac- presented with intermittent abdominal uated with a catheter [1]. -

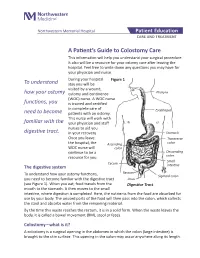

A Patient's Guide to Colostomy Care

Northwestern Memorial Hospital Patient Education CARE AND TREATMENT A Patient’s Guide to Colostomy Care This information will help you understand your surgical procedure. It also will be a resource for your ostomy care after leaving the hospital. Feel free to write down any questions you may have for your physician and nurse. During your hospital Figure 1 To understand stay you will be visited by a wound, how your ostomy ostomy and continence Pharynx (WOC) nurse. A WOC nurse functions, you is trained and certified in complete care of Esophagus need to become patients with an ostomy. This nurse will work with familiar with the your physician and staff nurses to aid you digestive tract. in your recovery. Stomach Once you leave Transverse the hospital, the Ascending colon WOC nurse will colon continue to be a Descending resource for you. colon Small Cecum The digestive system intestine Rectum To understand how your ostomy functions, Sigmoid colon you need to become familiar with the digestive tract Anus (see Figure 1). When you eat, food travels from the Digestive Tract mouth to the stomach. It then moves to the small intestine, where digestion is completed. Here, the nutrients from the food are absorbed for use by your body. The unused parts of the food will then pass into the colon, which collects the stool and absorbs water from the remaining material. By the time this waste reaches the rectum, it is in a solid form. When the waste leaves the body, it is called a bowel movement (BM), stool or feces. -

Understanding Your Ileostomy

Understanding Your Ileostomy The information provided in this guide is not medical advice and is not intended to substitute for the recommendations of your personal physician or other healthcare professional. This guide should not be used to seek help in a medical emergency. If you experience a medical emergency, seek medical treatment in person immediately. Life After Ostomy Surgery As a person who lives with an ostomy, I understand the importance of support and encouragement in those days, weeks, and even months after ostomy surgery. I also know the richness of life, and what it means to continue living my life as a happy and productive person. Can I shower? Can I swim? Can I still exercise? Will I still have a healthy love life? These are the questions that crossed my mind as I laid in my bed recovering from ostomy surgery. In the weeks following, I quickly discovered the answer to all of these questions for me was YES! I was the person who would empower myself to take the necessary steps and move forward past my stoma. Those who cared for and loved me would be there to support me through my progress and recovery. Everyone will have a different journey. There will be highs, and there will be lows. Although our experiences will differ, I encourage you to embrace the opportunity for a new beginning and not fear it. Remember that resources and support are available to you — you are not alone. Our experiences shape our character and allow us to grow as people. Try and grow from this experience and embrace the world around you. -

42 CFR Ch. IV (10–1–12 Edition) § 410.35

§ 410.35 42 CFR Ch. IV (10–1–12 Edition) the last screening mammography was (1) Colorectal cancer screening tests performed. means any of the following procedures furnished to an individual for the pur- [59 FR 49833, Sept. 30, 1994, as amended at 60 FR 14224, Mar. 16, 1995; 60 FR 63176, Dec. 8, pose of early detection of colorectal 1995; 62 FR 59100, Oct. 31, 1997; 63 FR 4596, cancer: Jan. 30, 1998] (i) Screening fecal-occult blood tests. (ii) Screening flexible § 410.35 X-ray therapy and other radi- sigmoidoscopies. ation therapy services: Scope. (iii) In the case of an individual at Medicare Part B pays for X-ray ther- high risk for colorectal cancer, screen- apy and other radiation therapy serv- ing colonoscopies. ices, including radium therapy and ra- (iv) Screening barium enemas. dioactive isotope therapy, and mate- (v) Other tests or procedures estab- rials and the services of technicians ad- lished by a national coverage deter- ministering the treatment. mination, and modifications to tests [51 FR 41339, Nov. 14, 1986. Redesignated at 55 under this paragraph, with such fre- FR 53522, Dec. 31, 1990] quency and payment limits as CMS de- termines appropriate, in consultation § 410.36 Medical supplies, appliances, with appropriate organizations and devices: Scope. (2) Screening fecal-occult blood test (a) Medicare Part B pays for the fol- means— lowing medical supplies, appliances (i) A guaiac-based test for peroxidase and devices: activity, testing two samples from (1) Surgical dressings, and splints, each of three consecutive stools, or, casts, and other devices used for reduc- (ii) Other tests as determined by the tion of fractures and dislocations. -

Double Barrel Wet Colostomy for Urinary and Fecal Diversion

Open Access Clinical Image J Urol Nephrol November 2017 Vol.:4, Issue:2 © All rights are reserved by Kang,et al. Journal of Double Barrel Wet Colostomy for Urology & Urinary and Fecal Diversion Nephrology Yu-Hao Xue and Chih-Hsiung Kang* Keywords: Double barrel wet colostomy; Urinary diversion; Fecal Department of Urology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital-Kaohsiung diversion Medical Center, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Republic of China Abstract Address for Correspondence A 60-year-old male who had a history of spinal cord injury received Chih-Hsiung Kang, Department of Urology, Chang Gung Memorial loop colostomy for fecal diversion and cystostomy for urinary diversion. Hospital - Kaohsiung Medical Center, Chang Gung University College Because he was diagnosed with muscle invasive bladder cancer, of Medicine, Taiwan, E- mail: [email protected] radical cystectomy and double barrel wet colostomy was conducted. Submission: 30 October, 2017 Computed tomography showed simultaneous urinary and fecal Accepted: 06 November, 2017 diversion and stone formation in the distal segment of colon conduit Published: 10 November, 2017 with urinary diversion. Copyright: © 2017 Kang CH, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, Introduction provided the original work is properly cited. In patients with an advanced primary or recurrent carcinoma, double-barreled wet colostomy can be used for pelvic exenteration Bilateral hydroureters and mild hydronephrosis were noted and and urinary tract reconstruction. It is a technique that separate we suspected the calculi impacted in bilateral ureteto-colostomy urinary and fecal diversion with a single abdominal stoma. -

Your Personal Wellness Guide Table of Con Tents

Your Personal Wellness Guide Table of Con TenTs InTroduction Understanding your digestive system . 3 What is an ileostomy? . 4 Why do I need an ileostomy? . 5 Types of ileostomies . 5 Who will teach me to care for my ileostomy? . 6 CarIng for Your Ileos TomY Wearing an ostomy appliance . 7 Pouch options . 8 Skin barrier options . 9 Draining your pouch . 10 Releasing gas from your pouch . 12 Routine skin care . 13 Changing your ostomy appliance . 14 daIlY ConsIderations & Troubleshoo ting Leakage and skin irritation . 17 Diet after ileostomy surgery . 17 Dehydration . 20 Managing gas and odor . 21 Bowel obstruction and food blockages . 22 Medication . 23 Ordering supplies . 23 Understanding and using ostomy accessory products . .24 When to call my Doctor or WOC Nurse . 26 lIvIng with an Ileos TomY Tips for daily living . 27 Exercise . .28 Travel . 29 Intimacy . .30 Clothing . 31 Talking about your ostomy . 32 resourCes . 33 glossarY . 34 noTes . .36 1 IntroductIon 2 Understanding Your Digestive Tract The human digestive tract is a series of organs designed to break down food, absorb nutrients and remove waste . It consists of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus .When we swallow our food, it passes into the esophagus which connects the mouth and the stomach . Once food enters the stomach, it is broken down into liquid form before moving on to the small intestine . By the time food enters into the small intestine, it is mostly liquid .The small intestine is a series of hollow loops measuring approximately 22 feet long .The small intestine’s job is to absorb nutrients that will fuel our bodies .After leaving the small intestine, what remains enters the large intestine which is also known as the colon .In the colon, most of the liquid is absorbed, leaving human waste (also called stool) behind . -

The Costs and Benefits of Moving to the ICD-10 Code Sets

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CIVIL JUSTICE service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS POPULATION AND AGING The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY organization providing objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges facing the public TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY and private sectors around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Science and Technology View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; -

Pdfs–For–Download/Ostomy–Care/Whats–Right–For– Me–-–Ileostomy 907602-806.Pdf on October 2, 2019

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Ileostomy Guide Ileostomy surgery is done for many different diseases and problems. Some conditions that can lead to ileostomy surgery include ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, familial polyposis, and cancer. Sometimes an ileostomy is only needed for a short time (temporary), or it may be needed for the rest of a person's life (permanent). For the thousands of people who have serious digestive diseases, an ileostomy can be the start of a new and healthier life. If you’ve had a chronic (long-term) problem or a life- threatening disease like cancer, you can look forward to feeling better after you recover from ileostomy surgery. You can also look forward to returning to most, if not all of the activities you enjoyed in the past. This guide will help you better understand ileostomy – what it is, why it’s needed, how it affects the normal digestive system1, and what changes it brings to a person’s life. ● What Is an Ileostomy? ● Types of Ileostomies and Pouching Systems ● Caring for an Ileostomy What Is an Ileostomy? An ileostomy is an opening in the belly (abdominal wall) that’s made during surgery. It's usually needed because a problem is causing the ileum to not work properly, or a disease is affecting that part of the colon and it needs to be removed. The end of the ileum (the lowest part of the small intestine) is brought through this opening to form a 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 stoma, usually on the lower right side of the abdomen. -

Current Status of Intestinal Transplantation

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.30.12.1771 on 1 December 1989. Downloaded from Gut, 1989, 30, 1771-1782 Progress report Current status of intestinal transplantation The successful development of clinical intestinal transplantation remains an exciting challenge for the transplant surgeon, immunologist, and gastro- enterologist. Bowel transplantation was first attempted in 1901 by Carrel who transplanted portions of small intestine into the neck of dogs.' Interest was rekindled in 1959 when Lillehei showed that autotransplantation of the small intestine into the dog was feasible.' Despite recent major improve- ments in techniques, however, and the introduction of new immuno- suppressive regimens which have seen the flourishing of liver, heart, heart/ lung and pancreatic transplant programmes, the clinical results of small intestinal transplantation remain dismal. Two major problems confront us; first, the complex immunological phenomena occurring after small bowel transplantation, which include both classical graft rejection and graft versus host disease, do not appear to be easily controlled by current immunosuppressive protocols, and require elaborate treatment of both graft and host.-' Second, the physiological functions of the graft are severely deranged by the process of transplantation and further immunological damage will not only hamper recovery but destroy the barrier functions so vital to recipient survival. http://gut.bmj.com/ A series of clinical intestinal transplants were performed in the early 1970s by several institutions, with only one survivor beyond two weeks. More recently small intestinal transplants have been carried out in several major transplant centres in Europe and North America and two European recipients have survived beyond six months (personal communication).