The Veeck Impact on Chicago: Master of the Joyful Illusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Sunday's Lineup 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY

The Official News of the 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp Sunday, January 21, 2018 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY Sunday’s The hard work and relentless dedica- “It is about how we bring families, Lineup tion needed to be a winning team and neighbors, friends, business associates, gain a postseason berth begins long be- and even strangers together. fore the crowds are in the stands for “But we all know it is the play on the Opening Day. It begins on the practice field that is the spark of it all.” fields, in the classroom, and in the The Indians won an American League 7:00 - 8:25 Breakfast at the complex weight room. -best 102 games in 2017 and are poised Today marks that beginning, when the to be one of the top teams in 2018 due to 7:30 - 8:00 Bat selection 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp its deeply talented core of players, award players make the first footprints at the -winning front office executives, com- Tribe’s Player Development Complex mitted ownership, and one of the best - if 8:30 - 8:55 Stretching on agility field here in Goodyear, AZ. not the best - managers in all of baseball Nestled in the scenic views of the Es- in Terry Francona. 9:00 -10:00 Instructional Clinics on fields trella Mountains just west of Phoenix, Named AL Manager of the year in the complex features six full practice both 2013 and 2016, the Tribe skipper fields, two half practice fields, an agility finished second for the award in 2017. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Chicago White Sox Charities Lots 1-52

CHICAGO WHITE SOX CHARITIES LOTS 1-52 Chicago White Sox Charities (CWSC) was launched in 1990 to support the Chicagoland community. CWSC provides annual financial, in-kind and emotional support to hundreds of Chicago-based organizations, including those who lead the fight against cancer and are dedicated to improving the lives of Chicago’s youth through education and health and well- ness programs and offer support to children and families in crisis. In the past year, CWSC awarded $2 million in grants and other donations. Recent contributions moved the team’s non-profit arm to more than $25 million in cumulative giving since its inception in 1990. Additional information about CWSC is available at whitesoxcharities.org. 1 Jim Rivera autographed Chicago White Sox 1959 style throwback jersey. Top of the line flannel jersey by Mitchell & Ness (size 44) is done in 1959 style and has “1959 Nellie Fox” embroi- dered on the front tail. The num- ber “7” appears on both the back and right sleeve (modified by the White Sox with outline of a “2” below). Signed “Jim Rivera” on the front in black marker rating 8 out of 10. No visible wear and 2 original retail tags remain affixed 1 to collar tag. Includes LOA from Chicago White Sox: EX/MT-NM 2 Billy Pierce c.2000s Chicago White Sox ($150-$250) professional model jersey and booklet. Includes pinstriped jersey done by the team for use at Old- Timers or tribute event has “Sox” team logo on the left front chest and number “19” on right. Num- ber also appears on the back. -

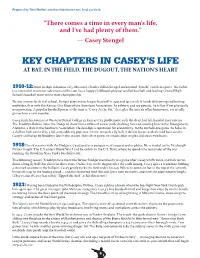

View Key Chapters of Casey's Life

Proposal by Toni Mollett, [email protected]; (775) 323-6776 “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them.” — Casey Stengel KEY CHAPTERS IN CASEY’S LIFE AT BAT, IN THE FIELD, THE DUGOUT, THE NATION’S HEART 1910-12: Born in 1890 in Kansas City, Missouri, Charles Dillon Stengel, nicknamed “Dutch,” excels in sports. His father is a successful insurance salesman and his son has a happy childhood, playing sandlot baseball and leading Central High School’s baseball team to the state championship. To save money for dental school, Stengel plays minor-league baseball in 1910 and 1911 as a left-handed throwing and batting outfielder, first with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. At 5-foot-11 and 175 pounds, he is fast if not physically overpowering. A popular baseball poem at the time is “Casey At the Bat,” that, plus the initials of his hometown, eventually garner him a new moniker. Casey finds his courses at Western Dental College in Kansas City problematic with the dearth of left-handed instruments. The Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers) show him a different career path, drafting him and sending him to the Montgomery, Alabama, a club in the Southern Association. He develops a reputation for eccentricity. In the outfield one game, he hides in a shallow hole covered by a lid, and suddenly pops out in time to catch a fly ball. A decent batter and talented base stealer, Casey is called up by Brooklyn late in the season. In his first game, he smacks four singles and steals two bases. -

A Remembrance of John Tortes Meyers (1880-1971) HENRY G

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 21-40 (2004) 21 The Catcher Was a Gahuilla: A Remembrance of John Tortes Meyers (1880-1971) HENRY G. KOERPER Dept. of Anthropology, Cypress College, Cypress, CA 90630 NATIVE American athletes achieved their greatest recognition in modern sports during the period from the turn of the century through the 1920s (Oxendine 1988). Among the notables were several Californians. For instance, Antonio Lubo, Elmer Busch, and Peter Calac all served as gridiron captains under Coach "Pop" Warner at Carlisle Indian Industrial School (Koerper 2000), where at various times they were teammates of the legendary Jim Thorpe (Peterson n.d.; Steckbeck 1951). Calac was Luiseno, Busch was Pomo, and Lubo was a Santa Rosa Mountain Cahuilla. Another athlete with ties to the Santa Rosa reservation, John Tortes Meyers (Fig. 1), developed into one of the best baseball catchers of his era. A roommate of Thorpe when the two played for the New York Nationals (Giants) (Fig. 2), then managed by John McGraw, "Chief" Meyers counted as battery mates at New York and elsewhere. Baseball Hall of Fame pitchers Christy Mathewson (see Robinson 1993), Rube Marquard (see Hynd 1996), and Walter "Big Train" Johnson (see Kavanagh 1995). For his many accomplishments, Meyers became the first Californian inducted into the American Indian Sports Hall of Fame, presently housed at Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas. This biographical overview chronicles the life of this gifted and courageous athlete who tenaciously embraced his Indian identity while operating mostly in a white world.' autionary notes attend the childhood biography of John Tortes Meyers. -

Kiiuimiiopici Aide, N

C-8 « THE BUNDAY OTAR, Wwhington, D. C. I, (I’NMV. 1. IWW in Opener ACC Club Slates pirCMUS CU Says 'M' Club Will Honor Sievers Os Mason-Dixon's jDeOrsey Baseball Award to Duke to Season At Saturday As Leading Athlete of Year fenotors Likely Draft Basketball Regulation Fete Roy Sievers, the ilsHeadedfor•*! Senators’ Princeton All-American quar- University Loy- f Coach Bill Murray of Dukl slugger Catholic and 1 C, Leo DeOrsey. member of, and waiver abuses, correct your who led the American terback, and Theodore Straus. ola of Tuesday i willreeelve a trophy In recogni- League In home runs and rana 140-pound Baltimore meet the Senators' board of dlree- bonus1 player situation, ask halfback and la- Deals Sought night Loyola to open the tion of the Blue Devils' selec- batted In this year, will be han- crosse star Hopkins /..afkmus; at Congress legislate at John yesterday to not to tion as the outstanding in Mason p Dixon Conference’s tori, predicted baae- football ored as "athlete of the year”’by the 1690’5, wi&be Cmilurf from Put C-l broadcastJ in minor league ter- team In tha Atlantic Coast Con- -1 inducted In basketball season. Game time ball Is headed toward antitrust , ritory and show Congress that the ”M” Club at Its annbal the Maryland Sports Hall of Is 8:30. feranoe at the ACO clubs 1 banquet December 14 at the . At the time enthrall Manager Cookie Lava- | regulation and aald the sport ; you mean to again eraaa from p.m. Fame. same the awards dinner at 8 Satur- Statler Hotel. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE the More We Learn, the Less We Know

A publication of the Society for American Baseball Research Business of Baseball Committee July 20, 2008 Summer 2008 The Commissioners and “Smart Power” The Return of Syndicate Baseball By Robert F. Lewis, II By Jeff Katz Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, has developed a A scourge of the National League during the 1890’s, geopolitical “smart power” model, used in this essay syndicate baseball, which allowed intertwined owner- to characterize the nine Major League Baseball (MLB) ship of franchises, was a serious detriment to true commissioners. Particular focus is on Judge Kenesaw competition. At the turn of the century, New York Gi- Mountain Landis, the first, and Allan H. “Bud” Selig, ants’ owner Andrew Freedman, along with John the current one. While intended to assess America’s Brush, owner of the Reds and shareholder in the Gi- use of power in global politics, Nye’s model is gener- ants, and two other National League owners attempted ally applicable in any leadership evaluation. Nye first to form the National League Base Ball Trust. With the describes “power” as “the ability to influence the be- support of Frank Robison of the Cardinals and Arthur havior of others to get the outcomes one wants.”1 In Soden of the Braves, the trust would foster common his model, Nye simply divides power into two con- ownership of all league clubs and assign players from trasting subcategories: hard and soft. For Nye, “hard one club to another, thereby influencing competition. power” is typically military or economic in the form Needing merely one more vote for passage, a vote to of threats (“sticks”) or inducements (“carrots”). -

Prices Realized

Mid-Summer Classic 2015 Prices Realized Lot Title Final Price 2 1932 NEWARK BEARS WORLD'S MINOR LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP GOLD BELT BUCKLE $2,022 PRESENTED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 3 1932 NEW YORK YANKEES SPRING TRAINING TEAM ORIGINAL TYPE I PHOTOGRAPH BY $1,343 THORNE (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 4 1936, 1937 AND 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES (WORLD CHAMPIONS) FIRST GENERATION 8" BY 10" $600 TEAM PHOTOGRAPHS (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 5 1937 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONS PRESENTATIONAL BROWN (BLACK) BAT $697 (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 6 1937 AMERICAN LEAGUE ALL-STAR TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY $5,141 COLLECTION) 7 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP GOLD POCKET WATCH PRESENTED TO $33,378 JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 8 INCREDIBLE 1938 NEW YORK YANKEES (WORLD CHAMPIONS) LARGE FORMAT 19" BY 11" $5,800 TEAM SIGNED PHOTOGRAPH (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 9 EXCEPTIONAL JOE DIMAGGIO VINTAGE SIGNED 1939 PHOTOGRAPH (JOHNNY MURPHY $968 COLLECTION) 10 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED PHOTO INSCRIBED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY $2,836 COLLECTION) 11 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED PHOTO INSCRIBED TO JOHNNY MURPHY (JOHNNY MURPHY $1,934 COLLECTION) 12 1940'S JOHNNY MURPHY H&B PROFESSIONAL MODEL GAME USED BAT AND 1960'S H&B GAME $930 READY BAT (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 13 1941, 1942 AND 1943 NEW YORK YANKEES WORLD CHAMPIONS PRESENTATIONAL BLACK $880 BATS (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 14 1941-43 NEW YORK YANKEES GROUP OF (4) FIRST GENERATION PHOTOGRAPHS (JOHNNY $364 MURPHY COLLECTION) 15 LOT OF (5) 1942-43 (YANKEES VS. CARDINALS) WORLD SERIES PROGRAMS (JOHNNY MURPHY $294 COLLECTION) 16 1946 NEW YORK YANKEES TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) $1,364 17 1946 NEW YORK YANKEES TEAM SIGNED BASEBALL (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) $576 18 1930'S THROUGH 1950'S JOHNNY MURPHY NEW YORK YANKEES AND BOSTON RED SOX $425 COLLECTION (JOHNNY MURPHY COLLECTION) 19 1960'S - EARLY 1970'S NEW YORK METS COLLECTION INC. -

First- See NASH

Baseball Club Owners Disagree On Later Opening ONE RUN MARGINS “Pavlowa” Cochrane Does His Stuff STICK’S BOWLERS Boston Moguls Favor WIN TELEPHONE How It's Done In DECIDED MAJOR Idea; Weil, . LEAGUE TITLE Heydler Dear Old Newark GAMES YESTERDAY it By DAM PARKER Cards Come Behind 8 to 7 Flammia Takes High Sin- Harridge Against / Count in Last Inning— gle, Anderson High Three and White A partial poll of major league club presidents indicates Cobs Edge Out Reds— High that the base- <*>»»mwm««»M**M****»»M****l*>*>**,**>M*>*t**M***,*t*>***’ fair support for John A. Heydler’s suggestion Manush Hero Again Average ball season be opened and closed later because of weather THE FROST BEING oil the pumpkin to such a depth at the local that all ball -were called conditions. apple orchards Wednesday afternoon games JACK CUDDY Gay Steck'a bowlers captured the a bunch of the boys decided to go over to the Yankees’ new farm The National League president oft, Press Staff Correspondent) 1932 In the Southern New in Newark and observe with what frills and furbelows a baseball sea- (United bunting at Cincinnati New York, April 14-r(UP)— made his suggestion Is In the International League. After having shivered England Telephone duckpln league son opened The champion Cardinals have yesterday. His proposal was op- iciest hours he has In since he Dr was climaxed last Friday through three of the put accompanied started after the National league which William and what not to a over Pep- posed Immediately by Cook to the Pole, your purveyor of news, gossip begs again. -

Stoning J&Fofsports

RADIO-TV, Page C-4—CLASSIFIED ADS, Pages C-5-1 . Ml .fe-; stoning J&fof SPORTS WASHINGTON, D. C., THURSDAY, C JANUARY 29, 1959 V Politics May Cloud Title After »*¦ Reds .. Rout U. S. Five 8L Sb R Spahn GETS FIVE-YEAR CONTRACT Russians Facing l| ,f Balks % wwwpißipifflßp3B» • .^adWß *,< * ' , v-'- Forfeit ** MraP« I&I^BkOI^ Unless \jpbm * mi, • % *JB •* v ....... ffinwfiUri -/¦.,. ><¦ •• /$, iJHkJH Lombardi Takes Post At Pay Offer; They Play China ¦J SANTIAGO, Chile, Jan. 29 u< (AP). Russia has finally . As Packers' Head Man J defeated a United States team Friend Signs GREEN BAY. Wis., Jan. 29 in basketball, swamping the (AP).“-Husky Vinoe Lombardi i representatives in By the Auocltted Preu American is about to shoulder the many Sfe a sport which originated in the Warren Spahn, the highest States. burdens of the Bay United paid pitcher in baseball, has Oreen It happened night Packers and hopes to get them last when joined the list of Milwaukee the Russians walloped the Braves who are not content out of last place in the Na- tional Football League. Air Force team, 62-37, in the with the salaries offered them game generally The 45-year-old Lombardi, that was ex- for 1959. |Rp : pected to decide the champion- | offensive strategist of the New i Spahn, ship who received about York Giants, was hired yester- of the World Amateur *» 9m $60,000 year, when he tourney. -4 m Wm' miMMMKsMBMMMMMW .*Mm Jam last won day as head coach and general basketball 22 games, said he expected a manager. vil ivy'*' A crowd of 24,000, largest of this year. -

Bill Veeck: Remembering the Good, the Bad and the In-Between on His 100Th Birthday

Bill Veeck: Remembering the good, the bad and the in-between on his 100th birthday By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, February 7th, 2014 A man with the ultimate positive image as a friend of the baseball fan, Bill Veeck might have been the first to say that, yeah, he had feet (in his case, one foot) of clay. A speed reader of books, Veeck knew all about protag- onists who had many sides, not every one of them he- roic. It made a balanced portrayal for the book con- sumer. In that case, Veeck, whose 100th birthday is being marked Feb. 9, was the ultimate balanced man. His baseball-owner opponents would have added “un” to the front of “balanced.” In the process of bearding the game’s establishment, in attempting to be in front of trends to make money, draw more fans and ad- vance a personal, liberal philosophy, star promoter Veeck both succeeded and failed. A typical Bill Veeck image from his In doing so, he became one of the most impactful prime. He was nicknamed "Sport men in Chicago baseball history. He was a true Re- Shirt Bill" for his refusal to wear ties naissance man, whose life impacted more than just in that button-down, dress-up era. events on the diamond. Veeck saved the White Sox for Chicago when there were no other local buyers in 1975. He gave Hall of Famer Tony La Russa his managerial start in 1979. Veeck prodded Har- ry Caray to start singing in the seventh inning, a tradition that has long outlasted Caray’s death.