Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Concussion Management Policies and Procedures Among Athletic Trainers in the Four Divisions of NCAA Collegiate Football

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2010 Analysis of concussion management policies and procedures among athletic trainers in the four divisions of NCAA collegiate football James D. Dorneman Jr. West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dorneman, James D. Jr., "Analysis of concussion management policies and procedures among athletic trainers in the four divisions of NCAA collegiate football" (2010). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4581. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4581 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analysis of Concussion Management Policies and Procedures among Athletic Trainers in the Four Divisions of NCAA Collegiate Football James D. Dorneman Jr., BS, ATC Thesis submitted to the College of Physical Activity and Sport Sciences At West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Athletic Training Michelle A. Sandrey, Ph.D, ATC, Chair Lynn Housner, Ph.D. -

Incidence, Awareness, and Reporting of Sport-Related Concussions in Manitoba High Schools

ORIGINAL ARTICLE COPYRIGHT © 2019 THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES INC. Incidence, Awareness, and Reporting of Sport-Related Concussions in Manitoba High Schools Glen L. Bergeron ABSTRACT: Background and Objectives: Federal and provincial governments in Canada are promoting provincial legislation to prevent and manage sport-related concussions (SRCs). The objective of this research was to determine the incidence of concussions in high school sport, the knowledge of the signs, symptoms, and consequences of SRC, and how likely student athletes are to report a concussion. Methods: A cross-sectional survey of athletes (N = 225) from multiple sports in five high schools in one Manitoba school division was conducted. Results: Participants in this study were well aware of the signs, symptoms, and consequences of SRC. Cognitive and emotional symptoms were the least recognized consequences. SRC is prevalent in high schools in both males and females across all sports. Of the 225 respondents, 35.3% reported having sustained an SRC. Less than half (45.5%) reported their concussion. Athletes purposely chose not to report a concussion in games (38.4%) and practices (33.8%). Two major barriers to reporting were feeling embarrassed (3.4/7) and finding it difficult (3.5/7) to report. There was, however, strong agreement (Mean 5.91/7, SD 0.09) when asked if they intend to report a concussion should they experience one in the future. Conclusions: The results suggest that high school athletes would benefit from more SRC education. Coaches and team medical staff must be trained to be vigilant for the mechanism, signs, and symptoms of injury in both game and practice situations. -

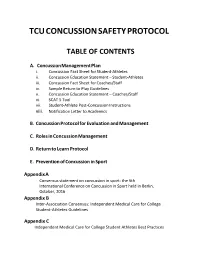

Tcu Concussion Safety Protocol

TCU CONCUSSION SAFETY PROTOCOL TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Concussion Management Plan i. Concussion Fact Sheet for Student-Athletes ii. Concussion Education Statement – Student-Athletes iii. Concussion Fact Sheet for Coaches/Staff iv. Sample Return to Play Guidelines v. Concussion Education Statement – Coaches/Staff vi. SCAT 5 Tool vii. Student-Athlete Post-Concussion Instructions viii. Notification Letter to Academics B. Concussion Protocol for Evaluation and Management C. Roles in Concussion Management D. Return to Learn Protocol E. Prevention of Concussion in Sport Appendix A Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Berlin, October, 2016 Appendix B Inter-Association Consensus: Independent Medical Care for College Student-Athletes Guidelines Appendix C Independent Medical Care for College Student Athletes Best Practices Concussion Management Plan: This plan is based on the most current evidence on concussions available as well as the recommended best practices for concussion management distributed by the NCAA Committee on Competitive Safeguards in Sport. As such, modifications may follow as the science of concussion diagnosis, education, and treatment advances. All incoming student-athletes, including transfer students and anyone new to the program, will be subject to this plan. PRE-PRACTICE EDUCATION: 1) Student athletes will undergo a formal education program on concussion in sport. Topics covered will include mechanism of injury, recognition of signs and symptoms of concussion, and strategies to avoid injury/prevent further sequelae. The ‘Concussion Fact Sheet for Student-Athletes’ provided by the NCAA will also be distributed at this time. This will be completed before participating in the first official practice session and will be directed by a staff athletic trainer and/or team physician. -

Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport

Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport July 2017 Funding provided by: Public Health Agency of Canada The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Suggested citation: Parachute. (2017). Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport. Toronto: Parachute. © Parachute – Leaders in Injury Prevention, 2017 Contents EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON CONCUSSIONS 5 ADDITIONAL REVIEW AND FEEDBACK 6 PARACHUTE PROJECT TEAM 6 OVERVIEW 7 PURPOSE 7 APPLICATION TO NON-SPORT RELATED CONCUSSION 7 WHO SHOULD USE THIS GUIDELINE? 7 HOW TO READ THIS GUIDELINE 8 ROLE OF CLINICAL JUDGMENT 8 KEY TERM DEFINITIONS 8 GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS 11 1. PRE-SEASON EDUCATION 12 2. HEAD INJURY RECOGNITION 13 3. ONSITE MEDICAL ASSESSMENT 14 4. MEDICAL ASSESSMENT 16 5. CONCUSSION MANAGEMENT 17 6. MULTIDISCIPLINARY CONCUSSION CARE 20 7. RETURN TO SPORT 21 CANADIAN SPORT CONCUSSION PATHWAY 23 GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS 25 EVIDENCE 25 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 25 UPDATES TO THIS GUIDELINE 26 APPENDIX: DOCUMENTS & TOOLS 27 PRE-SEASON CONCUSSION EDUCATION SHEET 29 MEDICAL ASSESSMENT LETTER 31 MEDICAL CLEARANCE LETTER 33 CONCUSSION RECOGNITION TOOL – 5TH EDITION (CRT5) 35 SPORT CONCUSSION ASSESSMENT TOOL – 5TH EDITION (SCAT5) 37 CHILD SPORT CONCUSSION ASSESSMENT TOOL – 5TH EDITION (CHILD SCAT5) 45 Contributors Expert Advisory Committee on Concussions Dr. Charles Tator, Co-Chair, MD, PhD, FRCSC, FACS Professor of Neurosurgery, University of Toronto Division of Neurosurgery and Canadian Concussion Centre, Toronto Western Hospital Dr. Michael Ellis, Co-Chair, BSc, MD, FRCSC Medical Director, Pan Am Concussion Program Dept. of Surgery and Pediatrics and Section of Neurosurgery, University of Manitoba Scientist, Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba Co-director, Canada North Concussion Network Dr. -

Rationale for Collaborative Action

Zero Tolerance for Concussions and other Neurotrauma in Ice Hockey: Rationale for Collaborative Action Aynsley M. Smith, RN, PhD, Michael J. Stuart, MD, David Dodick, MD, Matthew C Sorenson, JD, MA Jonathon T Finnoff, DO, David Krause, PT, DSc The Mayo Clinic Sports Medicine Center Hockey Research Team This document provides an overview of some research across sectors that might segue to an empirical basis for discussion by Summit attendees who seek a collaborative, multi sector solution to addressing the concussion challenge in hockey. 1 Preface We would like to state at the outset that Aynsley, Michael and our ice hockey research team has been humbled by the fantastic support of the faculty, steering and planning committees. Many of you have been addressing concussions your entire careers, are extremely well known and are well published in concussions in hockey and in related neurotrauma. The purpose of the Ice Hockey Summit: Action on Concussion is to provide background information to attendees so they can make informed decisions on the action plan needed to address the concussion epidemic. This pre-reading has been written to help ensure that we all have a basic understanding of the many dimensions of concussion. Hopefully, the six sectors identified and discussed in the pre-reading will serve as the studs in a framework for a collaborative action plan toward a solution. This document is not an exhaustive review of the influences on concussion. Our paradigm is influenced and simultaneously limited by our knowledge and professional experience. In many cases we are aware we have only cited only one or two publications written by our steering committee members. -

Concussions and the Marketing of Sports Equipment

S. HRG. 112–324 CONCUSSIONS AND THE MARKETING OF SPORTS EQUIPMENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 19, 2011 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 73–514 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:39 Mar 30, 2012 Jkt 073514 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\73514.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas, Ranking JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine BARBARA BOXER, California JIM DEMINT, South Carolina BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia MARK PRYOR, Arkansas ROY BLUNT, Missouri CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania TOM UDALL, New Mexico MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK WARNER, Virginia KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire MARK BEGICH, Alaska DEAN HELLER, Nevada ELLEN L. DONESKI, Staff Director JAMES REID, Deputy Staff Director BRUCE H. ANDREWS, General Counsel TODD BERTOSON, Republican Staff Director JARROD THOMPSON, Republican Deputy Staff Director REBECCA SEIDEL, Republican General Counsel and Chief Investigator (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:39 Mar 30, 2012 Jkt 073514 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\73514.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on October 19, 2011 ......................................................................... -

Parents' and Child's Concussion History As Predictors of Parental

Original Research Parents’ and Child’s Concussion History as Predictors of Parental Attitudes and Knowledge of Concussion Recognition and Response Melissa C. Kay,* MS, LAT, ATC, Johna K. Register-Mihalik,*† PhD, LAT, ATC, Cassie B. Ford,* PhD, Richelle M. Williams,‡ PhD, ATC, and Tamara C. Valovich McLeod,‡ PhD, ATC, FNATA Investigation performed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA, and A.T. Still University, Mesa, Arizona, USA Background: Parents’ knowledge of and attitudes toward concussions are often vital factors that affect care for injured adolescent athletes. It is important to understand the role that parents’ personal experiences with concussions play with regard to current concussion knowledge and attitudes so that clinicians may tailor their educational approaches. Purpose/Hypothesis: The purpose of this study was to determine an association between parents’ personal experiences and their child’s experiences with concussions as well as parental concussion knowledge and attitudes. We hypothesized that parents who have personally experienced symptoms or have a child who has experienced symptoms would have better knowledge and more favorable attitudes toward concussions. Study Design: Cross-sectional study; Level of evidence, 3. Methods: Parents of youth sport athletes (N ¼ 234 [82 male, 144 female, 8 unreported]; mean age, 44.0 ± 6.3 years) completed a prevalidated survey for concussion knowledge (maximum score possible, 29) and attitudes (maximum score possible, 49). Higher scores indicated better knowledge and more favorable attitudes toward concussive injuries. Parents reported the frequency of concussion diagnoses and/or experiences of concussion-related symptoms and whether their child had suffered a diagnosed concussion or experienced concussion symptoms (yes/no). -

Implications for Concussion Assessments and Return-To-Play Standards in Intercollegiate Football: How Are the Risks Managed? John J

Implications for concussion assessments and return-to-play standards in intercollegiate football: How are the risks managed? John J. Miller, John T. Wendt, & Nick Potter KEYWORDS: ABSTRACT Concussion, Guidelines The lack of understanding regarding the symptoms and effects of concussions by athletes and coaches can generate pressure on both the team physicians to diagnose concussions as well as the sport administrators who need to be aware what concussion protocols are being followed. The significance of appropriate diagnosis of a concussion and the return- to-play protocols may be complicated by the number of guidelines available as well as the reliance on the athlete to self-report the symptoms of a concussion. While the grading guidelines have advanced the use of uniform terminology and increased awareness of concussion signs and symptoms, the lack of scientific method in creating the concussion management guidelines called their effectiveness into question. A total of 65 head football athletic trainers were surveyed to determine how medical personnel at selected universities managed the risk of concussions in intercollegiate football. The results indicated that nearly 70% of the respondents indicated that between five to eight football players on their respective teams incurred a concussion during the season. However, no dominant guidelines for assessing a concussion were revealed as none of the guidelines were employed by more than 29% of the population. Finally, 50% did not believe that the same guidelines should be used for an initial concussion assessments or subsequent concussions. Because no two people can be diagnosed in exactly the same way, guidelines may inhibit proper treatment. -

Athlete / Parent Handbook for GHSA Sanctioned Interscholastic Athletic

Athlete / Parent Handbook for GHSA Sanctioned Interscholastic Athletic Activities 2015-2016 RREVISED 3/12 0 MEMBER SCHOOLS OF THE GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION ALPHARETTA HIGH SCHOOL BANNEKER HIGH SCHOOL CAMBRIDGE HIGH SCHOOL CENTENNIAL HIGH SCHOOL CHATTAHOOCHEE HIGH SCHOOL CREEKSIDE HIGH SCHOOL JOHNS CREEK HIGH SCHOOL LANGSTON HUGHES HIGH SCHOOL MILTON HIGH SCHOOL NORTH SPRINGS CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL NORTHVIEW HIGH SCHOOL RIVERWOOD INTERNATIONAL CHARTER SCHOOL ROSWELL HIGH SCHOOL TRI CITIES HIGH SCHOOL WESTLAKE HIGH SCHOOL It is the policy of the Fulton County School System not to discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, or disability in any employment practice, educational program or any other program, activity o r service. If you wish to make a complaint or request accommodation or modification due to discrimination in any program, activity or service, contact Compliance Coordinator, 786 Cleveland Avenue, SW, Atlanta, Georgia 30315 or telephone 470-254-6892. TTY 1-800-255-0135 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS for Athlete /Parent Handbook for GHSA Sanctioned Interscholastic Athletic Activities GHSA Member Schools of Fulton County Schools 1 Table of Contents 2 GHSA Sports Seasonal Calendar 3 Fulton County Testing Calendar 4 Statement of Philosophy 5 Objectives 5 Governances 5 Fulton County Board of Education (FCBOE) 5 Georgia High School Association (GHSA) 5 The Georgia High School Association (GHSA) Regions 5 National Federation of High Schools (NFHS) 5 Requirements for Participation 6 Pre-Participation Physical -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to The Joseph Sears School Page 3 Kenilworth School District No. 38 Strategic Plan Page 5 The Joseph Sears School Expectations Page 7 Parent Communication Protocol Procedure Page 8 Need Help - Who Do You Contact? Page 9 School Calendar 2019-2020 Calendar Page 11 District/School Website Calendar Page 12 Community/Extracurricular Activities Board of Education – District 38 Page 15 Chess Club Page 21 Community Events and Activities Page 24 Community Phone Numbers Page 14 Drop-In Calendar Page 20 Joseph Sears School Booster Club Meeting Schedule Page 19 Joseph Sears School Parents’ Volunteer Association Page 16 Kenilworth Cub Scouts/Boy Scouts Page 23 Kenilworth Girl Scouts Page 21 Kenilworth Park District Page 19 The Joseph Sears School Community Page 13 Faculty Directory Faculty and Staff by Grade Listing Page 25 Faculty and Staff by Alphabetical Listing Page 28 Class Lists Class Lists by Grade Page 31 Family Directory Alphabetical Listing of Families by Student Name Page 39 District/School Information Absences Page 117 Academic Promotion Page 97 Administrative Rules for the Reciprocal Reporting Agreement Page 158 Between the Village of Kenilworth Police Department and Kenilworth School District No. 38 Americans With Disabilities Act Page 98 Cellular Phone Usage Page 120 Classroom Placement Page 124 Code of Conduct Page 140 Concussion Information Page 110 Curriculum Information Page 89 Conduct of Visitors While on School Property Page 136 District Policies Page 125 Dress Code of Conduct Page 149 Drop Off/Pick Up -

Sport-Related Concussions in Adolescent Athletes: a Critical Public Health Problem for Which Prevention Remains an Elusive Goal

120 Review Article Sport-related concussions in adolescent athletes: a critical public health problem for which prevention remains an elusive goal Dilip R. Patel1, Diana Fidrocki1, Venu Parachuri2 1Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo Michigan, USA; 2Kaiser Permanente, Portland, Oregon, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Dilip R. Patel. Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, 1000, Oakland Drive, Kalamazoo Michigan, 49008, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Sport-related concussions in young athletes are common, generally under reported and often unrecognized. Preventive strategies include education, modification of sport rules, use of equipment such as headgears, face masks and mouth guards, and neck muscle training. Evidence is limited to support effectiveness of these preventive measures with the exception of rule modification in some sports. In the United States, laws have been enacted that require medical evaluation and clearance prior to return to play; however, evidence thus far does not show that laws have been effective in reducing the incidence of concussions in sport. More research is needed in all areas of preventive measures. Sports participation is a complex personal decision on the part of the adolescent and his or her family. They should be provided with all information on inherent risks so that they can make an informed decision. -

Review of Sports-Related Concussion: Potential for Application in Military Settings

Volume 44, Number 7, 2007 JRRDJRRD Pages 963–974 Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development Review of sports-related concussion: Potential for application in military settings Henry L. Lew, MD, PhD;1–3* Darryl Thomander, PhD;3 Kelvin T. L. Chew, MD;4 Joseph Bleiberg, PhD5 1Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Service, Department of Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA; 2Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA; 3Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Palo Alto, CA; 4Sports Medicine Service, Alexandra Hospital, Singapore; 5National Rehabilitation Hospital, Washington, DC Abstract—This article reviews current issues and practices in at 300,000 [3]. The U.S. military maintains an extensive the assessment and clinical management of sports-related concus- sports program that serves to help maintain and enhance sion. An estimated 300,000 sports-related concussions occur the physical conditioning and quality of life of service annually in the United States. Much of what has been learned men and women [4]. The number of military service about concussion in the sports arena can be applied to the diagno- members who participate annually in sports programs and sis and management of concussion in military settings. Current sustain sports-related concussions is currently unavail- military guidelines for assessing and managing concussion in war able, but we expect the incidence rate to be similar to that zones incorporate information and methods developed through sports-concussion research. We discuss the incidence, definition, of civilian athletes. Because of the current high use of and diagnosis of concussion; concussion grading scales; sideline improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in war, awareness of evaluation tools; neuropsychological assessment; return-to-action and concern regarding combat-related concussions sus- criteria; and complications of concussion.