A Case Study of a Character Education / Anti-Bullying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Efforts on Bullying in Schools

FEDERAL EFFORTS ON BULLYING IN SCHOOLS By Bethany D. Williams A capstone project submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Management Baltimore, Maryland January, 2014 ©2014 Bethany D. Williams All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements I would like to extend a heartfelt thanks to my lord and savior Jesus Christ, my family, and friends. Jesus Christ has been the source of direction throughout my life and I owe all of my success to him. My family has always encouraged me to reach for the stars. And my friends have been there to remind me that it is sometimes okay to relax and have fun. Through this collective unit of love, support, and guidance, I have found the necessary work-school-life balance needed to successfully complete my academic career while attending Johns Hopkins University. All of the thoughts and prayers along the way have been very much appreciated. ii Table of Contents Action-Forcing Event………………………………………………………………….1 Statement of the Problem……………………………………………………………...2 History…………………………………………………………………………………3 Background……………………………………………………………………………7 Key Players…………………………………………………………………………..14 Policy Proposal………………………………………………………………………15 Policy Analysis………………………………………………………………………16 Political Analysis…………………………………………………………………….23 Recommendation…………………………………………………………………….30 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………36 List of Charts Examples of Varying State Definitions for the Concept of Bullying………………..20 Curriculum Vitae Brief Biographical Sketch……………………………………………………………41 iii MEMORANDUM FOR: Rep. Linda Sanchez FROM: Bethany Williams SUBJECT: Federal Efforts on Bullying in Schools Action - Forcing Event On February 20, 2013, Duke University released a new study regarding the effects of bullying.1 This study suggests that the effects of childhood and adolescence bullying are long term and those who are victims and bullies are at a higher risk for psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and suicide. -

Curriculum Vitae Marilyn O'mallon, Ph.D., RN Associate Professor

Curriculum Vitae Marilyn O’Mallon, Ph.D., RN Associate Professor & Director School of Nursing (RN-BS, AGNP, DNP) Boise State University 1910 University Drive Boise, Idaho 83725-1840 (208) 426-4032 [email protected] Education Ph.D. (May, 2011) Nursing- Family Focused Research Hampton University Hampton Virginia 23668 Master of Science (December, 2003) Nursing- Clinical Nurse Specialist Armstrong Atlantic State University Savannah, Georgia 31419 Bachelor of Science (December, 2000) Nursing Armstrong Atlantic State University Savannah, Georgia 31419 Associate Degree (May 1997) Nursing Armstrong Atlantic State University Savannah, Georgia 31419 Professional Experience Associate Director & Professor Boise State University 06/2016-Present Associate Professor (Tenured) Armstrong State Univ. 08/2003-08/2016 Adjunct Online Faculty Boise State University 08/2011-Present Charge Nurse/Patient Advocate HAAF/Ft. Stewart, GA 02/1999-08/2003 Registered Nurse St Joseph’s SAV, GA 07/1997-02/1999 Registered Nurse Hospice Savannah, Inc. 07/1997-02/1999 Oral Surgery Tech Ft. Stewart, GA 02/1992-1995 OR Tech/Oral Surgery Tech Nurnberg, Germany 10/1991-10/1992 Nursing Assistant OB/GYN Nurnberg, Germany 08/1989-10/1990 Note: Sixteen (16) plus year’s civil service experience in a variety of U.S. Army health care facilities in Germany and the U.S., with 10 point spousal veterans preference due to spouse’s premature service related death during the first Gulf War (1991). RN licensure in GA, VA, and ID. Award Notable Alum October 2016 Armstrong State -

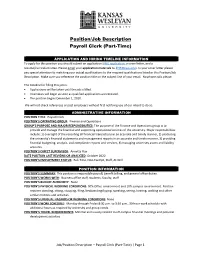

Position/Job Description Payroll Clerk (Part-Time)

Position/Job Description Payroll Clerk (Part-Time) APPLICATION AND HIRING TIMELINE INFORMATION To apply for this position you should submit an application KWU application, a cover letter, and a resume/curriculum vitae. Please email your application materials to ([email protected]). In your cover letter please pay special attention to matching your actual qualifications to the required qualifications listed in this Position/Job Description. Make sure you reference the position title on the subject line of your email. No phone calls please. The timeline for filling this job is: • Applications will be taken until the job is filled. • Interviews will begin as soon as qualified applications are received. • The position begins December 1, 2020. We will not check references or past employers without first notifying you of our intent to do so. ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION POSITION TITLE: Payroll Clerk POSITION’S OPERATING GROUP: Finance and Operations GROUP’S PURPOSE AND MAJOR RESPONSIBILITIES: The purpose of the Finance and Operations group is to provide and manage the financial and supporting operational services of the university. Major responsibilities include: 1) oversight of the recording all financial transactions in an accurate and timely manner, 2) producing the university’s financial statements and management reports in an accurate and timely manner, 3) providing financial budgeting, analysis, and compliance reports and services, 4) managing university assets and liability accounts POSITION’S DIRECT SUPERVISOR: Annetta Flax DATE POSITION LAST REVIEWS OR ANALYZED: October 2020 POSITION’S EMPLOYMENT STATUS: Full-Time, Non-Exempt, Staff, At-Will POSITION INFORMATION POSITION’S SUMMARY: This position is responsible payroll, benefit billing, and general office duties. -

Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005)

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2005 Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005) Darby Dickerson John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Education Law Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Darby Dickerson, Cyberbullies on Campus, 37 U. Tol. L. Rev. 51 (2005) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/643 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CYBERBULLIES ON CAMPUS Darby Dickerson * I. INTRODUCTION A new challenge facing educators is how to deal with the high-tech incivility that has crept onto our campuses. Technology has changed the way students approach learning, and has spawned new forms of rudeness. Students play computer games, check e-mail, watch DVDs, and participate in chat rooms during class. They answer ringing cell phones and dare to carry on conversations mid-lesson. Dealing with these types of incivilities is difficult enough, but another, more sinister e-culprit-the cyberbully-has also arrived on law school campuses. Cyberbullies exploit technology to control and intimidate others on campus.' They use web sites, blogs, and IMs2 to malign professors and classmates.3 They craft e-mails that are offensive, boorish, and cruel. They blast professors and administrators for grades given and policies passed; and, more often than not, they mix in hateful attacks on our character, motivations, physical attributes, and intellectual abilities.4 They disrupt classes, cause tension on campus, and interfere with our educational mission. -

Curriculum Vitae (Cv) Guide

CURRICULUM VITAE (CV) GUIDE cur●ric●u●lum vi●tae: Latin, course of (one’s) life A curriculum vitae is your first point of contact between you and your future colleagues. The role of a CV is to grab the interest of the reader and encourage him/her to look over your other application materials. For this reason, it is important to think about how you describe and format your experiences. What will your audience be looking for? What do you have that other applicants may not? Your job is to make it easy for your reader to find the strengths and achievements that you can bring to the position. Comparing the Curriculum Vitae and Resume: A curriculum vitae and a resume are similar in that both highlight one’s education and relevant experience. However, a CV tends to be longer and is used more widely when candidates have published works like scientific evidence or journals. Common for graduate students, a CV tends to include any research experience, teaching experience, and publications. CVs are more comprehensive as they are used when applying to positions where specific field knowledge or expertise is required. Like a resume, there is no one correct format for a CV- the key is formatting and organization! Curriculum Vitae Resume Goal: Obtain an academic position, research position, Goal: Obtain a nonacademic job or grant Audience: Potential nonacademic employers Audience: Fellow academic/researcher of similar field Structure: Minimal text, concise, achievement Structure: Text-heavy oriented bullet points Length: (Flexible) as long as necessary Length: Typically 1 page; limited to 2 page -Doctoral CVs typically 3-4 pages maximum -Master’s CVs typically 1-3 pages Content: Summary of most relevant skills and Content: Complete history of academic pursuits experiences tailored to ability to fit with specific (including teaching, research, awards, and service) job/company Tailored to highlight ability to conduct research/teach OR tailored to highlight ability to fit with specific job/field FORMATTING Typically, a CV should begin with contact information and education. -

Evaluation of the Evidence for the Trauma and Fantasy Models of Dissociation

Psychological Bulletin © 2012 American Psychological Association 2012, Vol. 138, No. 3, 550–588 0033-2909/12/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0027447 Evaluation of the Evidence for the Trauma and Fantasy Models of Dissociation Constance J. Dalenberg Bethany L. Brand California School of Professional Psychology at Alliant Towson University International University, San Diego David H. Gleaves and Martin J. Dorahy Richard J. Loewenstein University of Canterbury Sheppard Pratt Health System, Baltimore, Maryland, and University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore Etzel Carden˜a Paul A. Frewen Lund University University of Western Ontario Eve B. Carlson David Spiegel National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Menlo Park, Stanford University School of Medicine and Veterans Administration Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California The relationship between a reported history of trauma and dissociative symptoms has been explained in 2 conflicting ways. Pathological dissociation has been conceptualized as a response to antecedent traumatic stress and/or severe psychological adversity. Others have proposed that dissociation makes individuals prone to fantasy, thereby engendering confabulated memories of trauma. We examine data related to a series of 8 contrasting predictions based on the trauma model and the fantasy model of dissociation. In keeping with the trauma model, the relationship between trauma and dissociation was consistent and moderate in strength, and remained significant when objective measures of trauma were used. Dissociation was temporally related to trauma and trauma treatment, and was predictive of trauma history when fantasy proneness was controlled. Dissociation was not reliably associated with suggestibility, nor was there evidence for the fantasy model prediction of greater inaccuracy of recovered memory. -

Curriculum Vitae

August 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE MORRIS M. KLEINER Business Address: 260 Humphrey Center 301 19th Avenue, South University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455 U.S.A. Phone: (612) 625-2089 E-mail Address: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., University of Illinois, Department of Economics M.A., University of Illinois, School of Labor and Employment Relations B.S., Bradley University, Department of Economics EMPLOYMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, TWIN CITIES 1990 - AFL-CIO Chair Professor of Labor Policy 1987 - Professor, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, Center for Human Resources and Labor Studies, Carlson School of Management, and Department of Applied Economics Courses taught: Undergraduate - Personnel and Labor Relations Graduate - Labor Policy, Econometrics, Multivariate Techniques, Human Resources and Firm Performance, Evaluation of Micro Finance Programs, Organizational Structure and Performance, Organization Theory Foundations of High-Impact Human Resources and Industrial Relations, Public Policies on Work and Pay, Graduate Workshop, and Research Methods in Public Policy 1989 - Director, Center for Labor Policy 1989 Humphrey Medal, Outstanding Teaching Faculty Member 1991-1992 Director of Graduate Studies, Humphrey School of Public Affairs 1993-1995 University Faculty Representative to the Minnesota State Legislature 2000- 2016 Director of Graduate Studies, University Graduate Certificate in Policy Issues on Work and Pay 2004-06 Chair, All University Senate Committee on Faculty Affairs 2007-08 Juran Scholar, Carlson School of Management -

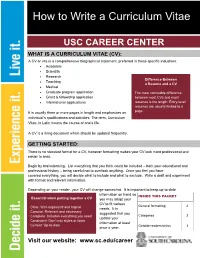

How to Write a Curriculum Vitae

How to Write a Curriculum Vitae USC CAREER CENTER WHAT IS A CURRICULUM VITAE (CV): A CV or vita is a comprehensive biographical statement, preferred in these specific industries: Academic Scientific Research Difference Between Teaching a Resume and a CV Medical Graduate program application The most noticeable difference Grant & fellowship application between most CVs and most International applications resumes is the length. Entry-level resumes are usually limited to a It is usually three or more pages in length and emphasizes an page. individual’s qualifications and activities. The term, Curriculum Vitae, in Latin means the course of one’s life. A CV is a living document which should be updated frequently. GETTING STARTED: There is no standard format for a CV, however formatting makes your CV look more professional and easier to read. Begin by brainstorming. List everything that you think could be included – both your educational and professional history – being careful not to overlook anything. Once you feel you have covered everything, you will decide what to include and what to exclude. Write a draft and experiment with format and relevant information. Depending on your reader, your CV will change somewhat. It is important to keep up-to-date information on hand so INSIDE THIS PACKET Essential when putting together a CV you may adapt your CV to fit various General formatting 2 Clear: Well-organized and logical needs. It is Concise: Relevant and necessary suggested that you Complete: Includes everything you need Categories 2 update your Consistent: Don’t mix styles or fonts information at least Current: Up-to-date Outside readers/critics 3 once a year, Visit our website: www.sc.edu/career GENERAL FORMATING: Form and Style Use 10-12 font size Tip Times New Roman and Arial are standard fonts Use bolding, italics, all CAPS, underlining, etc. -

Retrieval Can Increase Or Decrease Suggestibility Depending on How Memory Is Tested: the Importance of Source Complexity Jason C.K

Psychology Publications Psychology 7-2012 Retrieval Can Increase or Decrease Suggestibility Depending on How Memory is Tested: The Importance of Source Complexity Jason C.K. Chan Iowa State University, [email protected] Miko M. Wilford Iowa State University Katharine L. Hughes Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/psychology_pubs Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Evidence Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ psychology_pubs/16. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Retrieval Can Increase or Decrease Suggestibility Depending on How Memory is Tested: The mpI ortance of Source Complexity Abstract Taking an intervening test between learning episodes can enhance later source recollection. Paradoxically, testing can also increase people’s susceptibility to the misinformation effect – a finding termed retrieval- enhanced suggestibility (RES, Chan, Thomas, & Bulevich, 2009). We conducted three experiments to examine this apparent contradiction. Experiment 1 extended the RES effect to a new set of materials. Experiments 2 and 3 showed that testing can produce opposite effects on memory suggestibility depending on the complexity of the source test. Specifically, retrieval facilitated source discriminations when the test contained only items with unique source origins. -

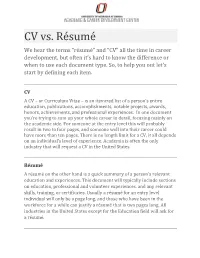

CV Vs. Résumé We Hear the Terms “Résumé” and “CV” All the Time in Career Development, but Often It’S Hard to Know the Difference Or When to Use Each Document Type

CV vs. Résumé We hear the terms “résumé” and “CV” all the time in career development, but often it’s hard to know the difference or when to use each document type. So, to help you out let’s start by defining each item. CV A CV – or Curriculum Vitae – is an itemized list of a person’s entire education, publications, accomplishments, notable projects, awards, honors, achievements, and professional experiences. In one document you’re trying to sum up your whole career in detail, focusing mainly on the academic side. For someone at the entry level this will probably result in two to four pages, and someone well into their career could have more than ten pages. There is no length limit for a CV, it all depends on an individual’s level of experience. Academia is often the only industry that will request a CV in the United States. Résumé A résumé on the other hand is a quick summary of a person’s relevant education and experiences. This document will typically include sections on education, professional and volunteer experiences, and any relevant skills, training, or certificates. Usually a résumé for an entry level individual will only be a page long, and those who have been in the workforce for a while can justify a résumé that is two pages long. All industries in the United States except for the Education field will ask for a résumé. Overview CV Resume Length 1 page (2 pages max!) unless No Length Limit there's a lot of relevant work experience Content Describes entire education Summarizes only relevant and professional career in education, experiences, and detail skills Use Most often used in the Used for all professional education industry industries expect education Examples Below, you will find examples of both a CV and a Resume using the same person. -

How to Write a Successful Curriculum Vitae Rose Filazzola

How to Write a Successful Curriculum Vitae Rose Filazzola 1 Index . Why write a C.V.? . What is a C.V.? . When should a CV be used? . Before you start . What information should a CV include? . What makes a good CV? . How long should a CV be? . Tips on presentation . Fonts . Different Types of CV . Targeting your CV . Emailed CVs and Web CVs . Summary . Websites to consult for Further Help . CV Sample 2 How to Write a Successful Curriculum Vitae Why write a CV? Nowadays, employers tend to receive thousands of applications for a job as soon as it is advertised on the job market. Therefore, it is vital that your letter should stand out from the thousands of CVs and letters that people are going to send. The first impression is always the most important one, therefore, you need a good, well- structured CV in order to attract the employers' attention. Your CV must sell you to a prospective employer and keep in mind that you are competing against other applicants who are also trying to sell themselves. So the challenge in CV writing is to be more appealing and attractive than the rest. This means that your curriculum vitae must be presented professionally, clearly and in a way that indicates you are an ideal candidate for the job, i.e., you possess the right skills, experience, behaviour, attitude, morality that the employer is seeking. The way you present your CV effectively demonstrates your ability to communicate and particularly to explain a professional business proposition. Different countries may have different requirements and styles for CV or resumes. -

THE CURRICULUM VITAE: an INTRODUCTION to PRESENTING and PROMOTING YOUR ACADEMIC CAREER Dr

THE CURRICULUM VITAE: AN INTRODUCTION TO PRESENTING AND PROMOTING YOUR ACADEMIC CAREER Dr. Angela M. Nelson, [email protected] Seminar Outcomes 1. Gain practical and useful information on how to prepare a CV. 2. Develop a strategy for creating a new CV or updating and revising a current CV. 3. Acquire tips for preparing a CV that can be read easily and quickly. RÉSUMÉS VS. VITAS: AN INTRODUCTION CVs and Folk Tradition 1. Folk tradition--common people, anonymous authorship & many versions; small, local group/community, disseminated by oral and non-oral methods; no formal training or skills 2. CV training is usually passed by word of mouth within a small local, academic community. Normally, no formal training or skills are learned, although more doctoral programs are offering courses where students learn about the CV, the job search, and etc. CV Key Terms Résumé • Origin of term is French: “summary” • A Résumé is a document that summarizes qualifications, education, experience, skills, and other items related to the writer’s objective. • Résumés are used by persons in almost every type of job or work other than higher education, especially for business employment. Curriculum Vitae • Origin of term is Latin: “the course of one’s life or career.” • Usage: “Vita,” “CV”; “Curricula Vitae,” plural form • A special type of résumé traditionally used in the academic community; an academic version of a résumé that features earned degrees, service, teaching, and research experience, publications, presentations, and related activities and experiences. It represents your past. • Vitas are used by anyone working in a Ph.D.-driven environment, such as higher education, think tanks, medical professions, science, and elite research & development groups.