Flathead National Forest Draft Revised Forest Plan, Appendix F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

![Sl N 06 [Converted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1326/sl-n-06-converted-521326.webp)

Sl N 06 [Converted]

PROHIBITIONS OPERATOR RESPONSIBILITIES PURPOSE AND CONTENTS OF THIS MAP It is prohibited to possess or operate an over-snow Operating a motor vehicle on National Forest System motor vehicle on the FLATHEAD NATIONAL FOREST ALL TRAVEL INFORMATION ON THIS MAP PERTAINS TO This map shows National Forest System roads, roads, National Forest System trails, and in areas on other than in accordance with these designations (36 OVER SNOW VEHICLE USE ONLY National Forest System trails, and areas on National National Forest System lands carries a greater respon- CFR 261.14), as per the Swan Lake Over Snow Forest System lands in the Swan Lake Ranger District sibility than operating that vehicle in a city or other Vehicle Use Map. and adjacent areas where use by over-snow vehicles developed setting. Not only must the vehicle operators FLATHEAD NATIONAL FOREST is allowed, restricted, or prohibited pursuant to 36 know and follow all applicable traffic laws, but they Violations of 36 CFR 261.14 are subject to a fine of up CFR 212.81. need to show concern for the environment as well as to $5,000 or imprisonment for up to 6 months or both SWAN LAKE other forest users. The misuse of motor vehicles can (18 U.S.C. 3571(e)). This prohibition applies regard- Designation of a road, trail, or area for over-snow lead to the temporary or permanent closure of any less of the presence or absence of signs. RANGER DISTRICT motor vehicle use should not be interpreted as designated road, trail, or area. Operators of motor encouraging or inviting use, or to imply that the road, vehicles are subject to State traffic law, including State This map does not display non-motorized uses and 2011 trail, or area is passable, or safe for travel. -

United States Department of the Interior Geological

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mineral resource potential of national forest RARE II and wilderness areas in Montana Compiled by Christopher E. Williams 1 and Robert C. Pearson2 Open-File Report 84-637 1984 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. 1 Present address 2 Denver, Colorado U.S. Environmental Protection Agency/NEIC Denver, Colorado CONTENTS (See also indices listings, p. 128-131) Page Introduction*........................................................... 1 Beaverhead National Forest............................................... 2 North Big Hole (1-001).............................................. 2 West Pioneer (1-006)................................................ 2 Eastern Pioneer Mountains (1-008)................................... 3 Middle Mountain-Tobacco Root (1-013)................................ 4 Potosi (1-014)...................................................... 5 Madison/Jack Creek Basin (1-549).................................... 5 West Big Hole (1-943)............................................... 6 Italian Peak (1-945)................................................ 7 Garfield Mountain (1-961)........................................... 7 Mt. Jefferson (1-962)............................................... 8 Bitterroot National Forest.............................................. 9 Stony Mountain (LI-BAD)............................................. 9 Allan Mountain (Ll-YAG)............................................ -

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex Newsletter 2020

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex VOLUME 29 2020 Newsletter A Note from your lead Ranger 2020 Limits of Acceptable Change Meeting Canceled At the USDA Forest Service, the health and well-being of our employees and the people we serve are our top priority. The LAC (Limits of Acceptable Change) Meeting scheduled for April 4, 2020 has been canceled at this time. We remain committed to public involvement in forest management. Information about the status of the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex will be provided through our website and social media. Every one of you interested in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex remains key for us as wilderness stewards in staying current on both land and social concerns, wilderness resource issues, and simply general observations. Your feedback on areas of interest remains appreciated! As such, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex managers, Forest Service representatives from the Helena-Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Flathead National Forests, and Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks representatives still look forward to hearing from you in other formats or future events. Lastly, we do plan to hold our managers meeting, albeit virtually. Good days to you. -Michael Muñoz, Ranger Rocky Mountain Ranger District, Helena-Lewis and Clark NF Introduction The Bob Marshall Wilderness complex is comprised of the Bob Marshall, Great Bear and Scapegoat designated wildernesses and also has ties with adjacent wildlands that provide the access and trailheads to the wilderness. We the managers or stewards, if you will, really value the opportunity to meet and talk with wilderness users, supporters and advocates. 2019/2020– Although we again, on the RMRD, experienced flooding events that damaged roads on NFS lands, as well as county roads, much of the remaining season was relatively quiet. -

Great American Outdoors Act | Legacy Restoration Fund | Fiscal Year 2021 Projects | Northern Region (R1) Region Forest Or Grassland Project Name State Cong

Great American Outdoors Act | Legacy Restoration Fund | Fiscal Year 2021 Projects | Northern Region (R1) Region Forest or Grassland Project Name State Cong. District Asset Type Project Description Built in 1962, this Visitor Center last saw updates over 25 years ago, hosts up to 45,000 visitors in a 4-month span. This project will fully renovate both floors to modernize the visitor center and increase usable space. This project will improve management of forests by educating visitors in fire aware practices. The project will improve signage, information and interpretive displays, modernize bathrooms, improve lighting, restore facility HVAC service, and Public Service conduct asbestos abatement. The visitor center provides tours and educational programs to rural schools, 50-60/year R01 Aerial Fire Depot Missoula Smokejumper Visitor Center Renovation MT MT-At Large Facility, totaling approximately 5,000 students. The project will improve ABA/ADA access and site compliance. The project Recreation Site augments visitor center and parachute loft access with interpretive displays and 24/7 accessible exterior storyboards. Work will improve the safety and remove environmental hazards from the Visitor Center. Work will be conducted in partnership with volunteers and museums to improve historical interpretation. The project has local support from MT Governor's Office of Outdoor Recreation via 8/26/20 letter. This project will recondition 500 miles on 54 roads across the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest. The recreation and commercial use such as timber haul and outfitter and guides are essential to the rural communities in southwest Recondition 500 Miles of Road in the Mountains of Southwest R01 Beaverhead-Deerlodge MT MT-At Large Road Montana. -

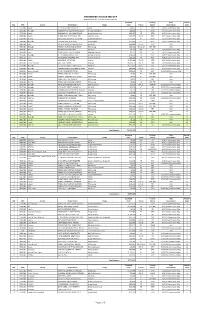

AMENDMENTS to 2019-2023 STIP Updated June 12, 2020, for Amendment 13 Estimated Funding Public Amend- Dist

AMENDMENTS TO 2019-2023 STIP Updated June 12, 2020, for Amendment 13 Estimated Funding Public Amend- Dist. UPN County Project Name Scope Costs Phases Source Involvement ment 1 9374-000 Ravalli SF 169 KOOTENAI CR RD SFTY Safety $28,655 IC HSIP 4/20/17 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9569-000 Missoula BROADWAY & TOOLE AVE-MISSOULA Int Upgrade/Signals $28,655 IC CMDP 9/27/12 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9778-000 Ravalli SKALKAHO CR - 1M E GRANTSDALE Bridge Replacement $308,477 PE STPB 6/27/19 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9780-000 Ravalli W FORK RD SLIDE REPAIR (S-473) Slide Correction $951,077 CN, CE STPS 6/21/18 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9786-000 Mineral I-90 STRUCTURES-W OF ALBERTON Bridge Replacement $6,175,824 PE NHPB 6/27/19 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9787-000 Missoula I-90 BR REHAB - ALBERTON Bridge Rehab $494,066 PE NHPB 6/27/19 Commission Mtg. 1 1 9693-000 Lake US-93 PETERSON MITIGATION SITE Wetlands $341,811 CN, CE STPX N/A 2 1 9760-000 Missoula RRXING-I-90 FRONTAGE-CLINTON RR Crossing $259,984 PE, CN, CE RRP-RRS N/A 2 1 6875-001 Mineral QUARTZ FLATS REST AREA Rest Area $12,235 RW IM 2/12/09 Commission Mtg. 3 1 9460-000 Lake ROUND BUTTE RD PATH-RONAN Bike/Ped Facilities $22,517 RW TA 6/27/19 Commission Mtg. 5 1 9613-001 Missoula SF 179 CLEARWATER JCT INTX Int Improvements $598,480 PE HSIP 4/24/19 Commission Mtg. 6 1 9614-001 Lake SF 179 EAGLE PASS TRAIL SFTY Int Improvements $153,299 PE HSIP 4/24/19 Commission Mtg. -

Notices Federal Register Vol

22716 Notices Federal Register Vol. 85, No. 79 Thursday, April 23, 2020 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER Northern Region Forest Supervisor Dial: 888–254–3590, Conference ID: contains documents other than rules or and District Ranger Decisions for: 1556806. proposed rules that are applicable to the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: public. Notices of hearings and investigations, Forest—The Montana Standard; committee meetings, agency decisions and Melissa Wojnaroski, DFO, at Bitterroot National Forest—Ravalli [email protected] or 312–353– rulings, delegations of authority, filing of Republic; petitions and applications and agency 8311. statements of organization and functions are Custer Gallatin National Forest— Billings Gazette and Bozeman Chronicle SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Members examples of documents appearing in this of the public can listen to these section. (Montana); Rapid City Journal (South Dakota); discussions. These meetings are Dakota Prairie Grasslands—Bismarck available to the public through the DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Tribune (North and South Dakota); above call in number. Any interested Flathead National Forest—Daily Inter member of the public may call this Forest Service Lake; number and listen to the meeting. An Helena-Lewis and Clark National open comment period will be provided Newspapers for Publication of Legal Forest—Helena Independent Record; to allow members of the public to make Notices in the Northern Region Idaho Panhandle National Forests— a statement as time allows. The conference call operator will ask callers AGENCY: Forest Service, USDA. Coeur d’Alene Press; Kootenai National Forest—The to identify themselves, the organization ACTION: Notice. Missoulian; they are affiliated with (if any), and an email address prior to placing callers SUMMARY: This notice lists the Lolo National Forest—The newspapers that will be used by all Missoulian; into the conference room. -

Planning Record Index for the Flathead National Forest 2018 Land Management Plan and NCDE Grizzly Bear Amendments

Planning Record Index for the Flathead National Forest 2018 Land Management Plan and NCDE Grizzly Bear Amendments Exhibit Author Description 00001 Flathead National Forest Public Involvement List of Meetings September 2013 to May 2015 00002 Chip Weber (forest supervisor, Flathead letter inviting Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes resource managers to meet with Flathead National Forest National Forest) planning team 00003 consultation record of meeting Jan. 21, 2015, with Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes 00004 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision Middle Fork and South Fork Geographic Area Meeting – Mapping Management Areas Draft Summary 00005 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision Swan Valley and Salish Mountains Geographic Area Meeting – Mapping Management Areas Draft Summary 00006 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision Hungry Horse and North Fork Geographic Area Meeting – Mapping Management Areas Draft Summary 00007 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Stakeholder Collaboration Forest-Wide Meeting – Mapping Management Areas Draft Summary 00008 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision - Salish Mountains Geographic Area Meeting Draft Summary 00009 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision - Swan Valley Geographic Area Meeting Draft Summary 00010 Meridian Institute Flathead National Forest Plan Revision - Hungry Horse, Middle Fork, and South Fork - Geographic Areas Meeting - Draft Summary 00011 Meridian Institute Flathead National -

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks ...Montana State Parks

Eureka GLACIER NATIONAL KOOTENAI PARK NATIONAL BLACKFEET INDIAN Scobey Plentywood FOREST FLATHEAD RESERVATION Cut Bank NATIONAL Browning Chinook FOREST Columbia Shelby Falls Libby Havre FORT PECK INDIAN Whitefish Fort RESERVATION ROCKY BOY’S Belknap Kalispell INDIAN Agency RESERVATION Malta Glasgow Wolf Somers FORT BELKNAP Point Bigfork Conrad INDIAN Lakeside RESERVATION Thompson Falls Choteau Sidney Polson Fort Benton FLATHEAD Great INDIAN Ronan RESERVATION Falls Plains LEWIS & CLARK NATIONAL LOLO FOREST NATIONAL Seeley Lake FOREST Glendive Discover and reserve camping, lodging, Lewistown permits, tours and more at America's parks, Missoula Lincoln forests, monuments and other public lands . www.recreation.gov Bonner HELENA Lolo Clinton NATIONAL LEWIS & Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks . www.fwp.mt.gov FOREST CLARK NATIONAL Helena East FOREST Montana State Parks . www.stateparks.mt.gov Helena Stevensville Montana Bureau of Land Management . www.blm.gov/mt/st/en.html Clancy City Miles City Deer Roundup Baker Hamilton Lodge Forsyth Bureau of Reclamation . www.usbr.gov/gp/recreation/ Townsend montana_recreation.html BITTERROOT NATIONAL Anaconda Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. www.dnrc.mt.gov/ FOREST Butte Big Colstrip Manhattan Timber National Recreation Area . www.nps.gov/state/mt/index.htm Three Whitehall Forks Laurel Billings Lame National Forest . www.fs.fed.us/ Columbus Hardin Crow Deer Livingston Agency Bozeman Absarokee NORTHERN CROW INDIAN CHEYENNE Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest . www.fs.usda.gov/bdnf RESERVATION INDIAN Bitterroot National Forest . www.fs.usda.gov/bitterroot RESERVATION CUSTER NATIONAL Custer Gallatin National Forest . www.fs.usda.gov/main/custergallatin/home FOREST Big Sky GALLATIN Red Flathead National Forest . www.fs.usda.gov/flathead Dillon Lodge NATIONAL BIGHORN Helena National Forest . -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Flathead National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Flathead National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R1 - Northern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Bob Marshall Wilderness - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:04/2015 04/2015 Debbie Mucklow Outfitter and Guide Permit - Special use management Scoping Start 03/29/2014 406-758-6464 Reissuance [email protected] CE Description: Reissuance of existing outfitter and guide permits in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=44827 Location: UNIT - Swan Lake Ranger District, Hungry Horse Ranger District, Lincoln Ranger District, Rocky Mountain Ranger District, Seeley Lake Ranger District, Spotted Bear Ranger District. STATE - Montana. COUNTY - Flathead, Glacier, Lewis and Clark, Missoula, Pondera, Powell, Teton. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. FNF Plan Revision & NCDE - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:05/2018 06/2018 Joseph Krueger GBCS Amendment to the Lolo, Objection Period Legal Notice 406-758-5243 Helena, Lewis & Clark,and 12/14/2017 [email protected] Kootenai NFs Description: The Flathead NF is revising their forest plan and preparing an amendment providing relevant direction from the EIS NCDE Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy into the forest plans for the Lolo, Helena, Kootenai, and Lewis & Clark National Forests. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/goto/flathead/fpr Location: UNIT - Kootenai National Forest All Units, Lewis And Clark National Forest All Units, Flathead National Forest All Units, Helena National Forest All Units, Lolo National Forest All Units. -

Keeping the Crown of the Continent Connected an Interagency US2 Connectivity Workshop Report

Keeping the Crown of the Continent Connected An Interagency US2 Connectivity Workshop Report John Waller, Glacier National Park Tabitha Graves, U.S. Geological Survey Please cite as: Waller, J. and Graves, T. (2018). Keeping the Crown of the Continent Connected: an Interagency US2 Connectivity Workshop Report. Unpublished report. National Park Service, Glacier National Park. 30 pp. Introduction At over 2.5 million acres, Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex form one of the largest protected areas in the continental United States. Straddling the Continental Divide, these two areas form a vital linkage between vast areas of public land to the south towards Yellowstone, and contiguous protected areas north of the US-Canada border. However, US Highway 2 (US2) and the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad separate Glacier National Park to the north from the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex to the south. While this narrow ribbon of development passes through primarily public land, it is bordered in some areas by narrow strips of private land. Many of these private parcels are developed as ranches, campgrounds, or seasonal and permanent home sites and businesses. Currently, two of the defining characteristics of this portion of the US2 corridor are relatively low highway traffic volume, but relatively high railroad traffic volume. The highway had a 2017 annual average daily traffic volume (AADT) of 1859 vehicles, far less than other interstate highways around the region which often have AADTs well over 10,000. Conversely, the BNSF railroad line currently carries about 33 trains per day, making it one of the busier railroad lines in the northwestern US. -

WG Flathead LRMP Revision Scoping Comments V2

May 15, 2015 Ms. Sharon LeBrecque, Acting Forest Supervisor Forest Plan Revision Flathead National Forest 650 Wolfpack Way Kalispell, MT 59901 [email protected] Sent via email and certified mail this date Re: Notice of Intent to revise the Flathead National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan and draft an amendment incorporating portions of the NCDE Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy, and prepare an associated Environmental Impact Statement. Dear Ms. LeBrecque: We appreciate the opportunity to submit the attached comments in response to the Notice of Intent to revise the Flathead National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan and prepare an associated Environmental Impact Statement. WildEarth Guardians is a non-profit organization dedicated to maintaining, protecting, and restoring the native ecosystems of Montana and the American West, with some 66,500 supporters. WildEarth Guardians has an organizational interest in the proper and lawful management of the Flathead National Forest. Our members, staff, and board members participate in a wide range of hunting, fishing and other recreational activities on the Flathead National Forest. Upon reviewing this Proposed Action of the Revised Forest Plan, we believe that such a revision—and the resulting environmental and legal consequences—will likely impact the interests of WildEarth Guardians’ members by threatening the survival of fish, wildlife and plants on the Flathead, increasing the possibility of recreational user conflicts, and having other significant and lasting impacts on the environment. Table of Contents I. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 II. General Comments about the Planning Process……………………………………………..3 III. Grizzly Bear Management and Amendments …………………………………………………3 IV. Bull Trout ……………………………………………………………………………………………………23 V. Designated, Management, and Geographic Areas ……………………………...…………36 VI.