The Landscape Legacy of Deer Parks in Kent & Bromley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Darwin's Parish Downe, Kent

A HISTORY OF DARWIN’S PARISH DOWNE, KENT BY O. J. R. HOW ARTH, Ph.D. AND ELEANOR K. HOWARTH WITH A FOREWORD BY SIR ARTHUR KEITH, F.R.S. SOUTHAMPTON : RUSSELL & CO. (SOUTHERN COUNTIES) LTD. CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE Foreword. B y Sir A rthur K eith, F.R.S. v A cknowledgement . viii I Site and P re-history ..... i II T he E arly M anor ..... 7 III T he Church an d its R egisters . 25 IV Some of t h e M inisters ..... 36 V Parish A ccounts and A ssessments . 41 VI T he People ....... 47 V II Some E arly F amilies (the M annings and others) . - 5 i VIII T he L ubbocks, of Htgh E lms . 69 IX T he D arwtns, of D own H ouse . .75 N ote on Chief Sources of Information . 87 iii FOREWORD By S ir A rth u r K e it h , F.R .S. I IE story of how Dr. Howarth and I became resi T dents of the parish of Downe, Kent— Darwin’s parish— and interested in its affairs, both ancient and modern, begins at No. 80 Wimpole Street, the home of a distinguished surgeon, Sir Buckston Browne, on the morning of Thursday, September 1, 1927. On opening The Times of that morning and running his eye over its chief contents before sitting down to breakfast, Sir Buck ston observed that the British Association for the Ad vancement of Science—of which one of the authors of this book was and is Secretary— had assembled in Leeds and that on the previous evening the president had delivered the address with which each annual meeting opens. -

General Index

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 123 ) GENERAL INDEX. Abbey, Premonstratensian of West Arch. Cant. LV, Pottery, 70, 71, 76, 78. Langdon, similar architecture to Arch. Cant. LVII, Court Rolls, Manor Walmer and Lydden, 85. of Farnborough, 7. Abbeys in Kent: St. Augustine, Arch. Cant. (1945), Wall of small Reculver, Dover, 19. bricks, 115. Abbot Beornheab, five entries relating Arch, Jour. XCV, Proportions, 5. to, 22. Archbishop Plegmund, 890, 22. Abbot Feologeld of Dover, later Architectural Notes on Kent Churches, Archbishop, 19, 21. Plans of, and Brief, by F. 0. Elliston- Abbots of Dover, Reculver, St. Erwood, F.S.A., (4 plans), 1-6. Augustine's, 21-28 Architecture, Spurious Gothic, 93. Abrinciis, Simon de, held Honour of Arts in Early England, The, 6. Folkestone, 85. Arundell, Sir John of Trerice, 98; Acleah, Council at, 805, 23. en. (1) Margaret, d. of Sir Hugh Adams, Richard, brass extant, 102. Courtenay, 97; (2) Ann, d. of Sir Adrian, Abbot of St. Augustine's, 674, Walter Moyle, 96. 26. Ash, Soil and acreage of, 82, 84. Aethelheah, Abbot of Reculver after Ashdown, John of Hover, 121 King Cenulf of /uremia had seized Ashford-Godmersham Downs on 3rd. revenues, 21, 28. Roman Road, 29, 30. Aethelheard, Mercian Archbishop at Ashtead, medieval ware, 74. Council of Clovesho, 23. Auberville, Estates in Oxney passed to Aethilmer, Abbot of Reculver, 699, 27. family of Criol or Kerial, 85. Afleerers, 16. Auberville, William, founded Abbey Agger or Embankment of Roman of W. Langdon, 84, 91. -

Downe to Pratts Bottom

Bromley Pub Walk No. 12 Downe to Pratts Bottom A walk through farmland and woods, including Downe Bank Nature Reserve, where Charles Darwin studied orchids. Please read the Bromley Pub Walks introductory notes for explanation about information provided in these walking guides Approx. Distance: 3.5 miles Approx. Time: 1.5 hours Gradients: Parts of the walk includes paths with gradients, including steps Type(s) of path(s): Mostly gravel paths, some grass in fields Stiles / Gates: This route has several kissing gates and a stile Road Walking: There are four short sections with no footway: (ie. roads without footway) . Cudham Rd, Downe (approx. 200 yards) . Cudham Lane North (approx. 80 yards) . Mace Lane (approx. 400 yards) . Snag Lane (approx. 200 yards) Livestock or crops: This route includes fields which may contain livestock, crops or horses OS Grid References: . Downe: TQ 432616 . Pratts Bottom: TQ 472623 Maps . OS 1:25 000, No. 147 . The entire route is covered by Bromley Council’s walking leaflets ‘Cudham’ and ‘Green St Green’ which include maps Connections to other From Downe: Bromley Pub Walks: . 04 to Keston . 06 to Leaves Green . 08 to Farnborough . 11 to Green St Green . 13 to Cudham . 14 to Berrys Green . 15 to Biggin Hill (Black Horse) The Bromley Pub Walk guides have been prepared and published by Bromley CAMRA to encourage members and others to enjoy walking in the rural areas of Bromley and to visit the many pubs and clubs on the routes. If you have any comments about the Bromley Pub Walk guides please send an email to: [email protected] © 2019 Bromley CAMRA Page 1 v1.0 Bromley Pub Walk No. -

Core Strategy

APPENDIX 2 AREA PEN PORTRAITS 1 Beckenham Copers Cope & Kangley Bridge 2 Bickley 3 Bromley Common 4 Chislehurst 5 Clock House, Elmers End & Eden Park 6 Cray Valley, St Paul's Cray & St. Mary Cray 7 Crofton and Farnborough 8 Crystal Palace, Penge & Anerley 9 Hayes 10 Keston 11 Mottingham 12 Shortlands, Park Langley & Pickhurst 13 West Wickham & Coney Hall Places within the London Borough of Bromley Ravensbourne, Plaistow & Sundridge Mottingham Beckenham Copers Cope Bromley Bickley & Kangley Bridge Town Chislehurst Crystal Palace Cray Valley, St Paul's Penge and Anerley Cray & St. Mary Cray Shortlands, Park Eastern Green Belt Langley & Pickhurst Clock House, Elmers Petts Wood & Poverest End & Eden Park Orpington, Ramsden West Wickham & Coney Hall & Goddington Hayes Crofton & Farnborough Bromley Common Chelsfield, Green Street Green & Pratts Bottom Keston Darwin & Green Belt Biggin Hill Settlements Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database 2011. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100017661. BECKENHAM COPERS COPE & KANGLEY BRIDGE Character The introduction of the railway in mid-Victorian times saw Beckenham develop from a small village into a town on the edge of suburbia. The majority of dwellings in the area are Victorian with some 1940’s and 50’s flats and houses. On the whole houses tend to have fair sized gardens; however, where there are smaller dwellings and flatted developments there is a lack of available off-street parking. During the later part of the 20th century a significant number of Victorian villas were converted or replaced by modern blocks of flats or housing. Ten conservation areas have been established to help preserve and enhance the appearance of the area reflecting the historic character of the area. -

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

Index Archives 1-10 1979 to 1988

ORPINGTON & DISTRICT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY INDEX TO ARCHIVES VOLUMES 1-10 (1979-1988) INTRODUCTION This index comprises the ODAS Newsletter and Volumes 1-10 of Archives. My thanks go to Carol Springall, Michael Meekums and Hazel Shave for compiling this index. If you would like copies of any of these articles please contact Michael Mcekums. For information the ODAS Newsletters were published from 1975-1978 and the indexing shows this. Regarding Archives, the following table gives the year in which each Volume was published: Volume I published 1979 Volume 2 " 1980 Volume 3 " 1981 Volume 4 " 1982 Volume 5 " 1983 Volume 6 " 1984 Volume 7 II 1985 Volume 8 " 1986 Volume 9 " 1987 Volume 10 " ]988 When using the index please note the following points: 1. TIle section titles are for ease of reference. 2. "Fordcroft" and "Poverest" are sites at the same location. 3. "Crofton Roman Villa" is sometimes referred to as "Orpington Roman Villa" and "Villa Orpus''. To be consistent we have indexed it as "Crofton Roman Villa". Brenda Rogers Chairman rG Orpington & District Archaeological Society 1998 ARCHIVES AGM REPORTS Volume~umber/Page 5th AGM - 1978 1.1,7 6th AGM - 1979 2,1,8 7th A("M - 1980 3,1,14 8th AGM - 1981 4,1,7 9th AGM - 1982 5,1,10 IOth AGM - 1983 6,1,74 11th AGM - 1984 7,1,10 12th AGM - 1985 8,1,6 13th AGM - 1986 9,1,2 14th AGM - 1987 10,1,2 BlJRIALS Romano- Blitish Orpington, Fordcroft 3,1,13 May Avenue 3,1,13 Ramsden Road 3,1,13 Poverest 5,1,8 ......................................................... -

Chislehurst Conservation Area

CHISLEHURST CONSERVATION AREA A Study compiled and written for The Chislehurst Society By Mary S Holt August 1992 (updated February 2008) Chislehurst Conservation Area Study Editors note Mary Holt’s 1992 study of the Chislehurst Conservation Area is full of interest at a number of different levels. Not only did she describe the then current features of all the roads in the Conservation Area, she added historical information, which helps make sense of the position at the time she was writing. She also noted the practical issues faced by residents and others going about their business in these areas. Finally, she noted the then understood Conservation Area Objectives. The original study was completed in 1992, and we felt we should bring it up to date in 2008. In doing so, however, we have identified only significant changes which we believe Mary would have wanted to reflect had she been editing the original study now. In fact there are relatively few such changes given the size of the conservation area. These changes are identified in square brackets, so that readers are able to read the original study, and see what changes have been made to it in bringing it up to date. The updated study will be published on the Chislehurst Society’s website, and to make it more accessible in that format, we have changed some of the layout, and added some old photographs of Chislehurst taken in the first three decades of the 20th Century to illustrate the text. February 2008 Mary at the entrance to the Hawkwood Estate in 1989 at the time that the National Trust were proposing that a golf course should be built here. -

Appendix B List of Site Applicable to the PSPO. All Carriageways

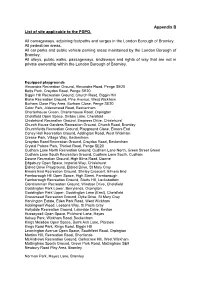

Appendix B List of site applicable to the PSPO. All carriageways, adjoining footpaths and verges in the London Borough of Bromley. All pedestrian areas. All car parks and public vehicle parking areas maintained by the London Borough of Bromley. All alleys, public walks, passageways, bridleways and rights of way that are not in private ownership within the London Borough of Bromley. Equipped playgrounds Alexandra Recreation Ground, Alexandra Road, Penge SE20 Betts Park, Croydon Road, Penge SE20 Biggin Hill Recreation Ground, Church Road, Biggin Hill Blake Recreation Ground, Pine Avenue, West Wickham Burham Close Play Area, Burham Close, Penge SE20 Cator Park, Aldersmead Road, Beckenham Charterhouse Green, Charterhouse Road, Orpington Chelsfield Open Space, Skibbs Lane, Chelsfield Chislehurst Recreation Ground, Empress Drive, Chislehurst Church House Gardens Recreation Ground, Church Road, Bromley Churchfields Recreation Ground, Playground Close, Elmers End Coney Hall Recreation Ground, Addington Road, West Wickham Crease Park, Village Way, Beckenham Croydon Road Recreation Ground, Croydon Road, Beckenham Crystal Palace Park, Thicket Road, Penge SE20 Cudham Lane North Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane North, Green Street Green Cudham Lane South Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane South, Cudham Downe Recreation Ground, High Elms Road, Downe Edgebury Open Space, Imperial Way, Chislehurst Eldred Drive Playground, Eldred Drive, St Mary Cray Elmers End Recreation Ground, Shirley Crescent, Elmers End Farnborough Hill Open Space, High Street, Farnborough -

The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond

T H A M E S V A L L E Y AARCHAEOLOGICALRCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment by Tim Dawson Site Code PLR12/80 (TQ 1793 7520) The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment for Renworth Homes (Southern) Ltd In support of a detailed planning application and Conservation Area Consent application for the erection of three new townhouses, with car parking and conversion of existing school building for six residential units with car parking by Tim Dawson Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code PLR 12/80 AUGUST 2012 Summary Site name: The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Grid reference: TQ 17925 75200 Site activity: Desk-based heritage assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Tim Dawson Site code: PLR 12/80 Area of site: c.0.12ha Summary of results: The Old School lies in an area of high archaeological potential with finds and features dating from the Palaeolithic period onwards being discovered nearby. Richmond itself was an important centre with its royal palace dating from the medieval period. While construction of the school in 1870 is likely to have disturbed at least the most shallow archaeological deposits, the area under the playground is less likely to have been truncated allowing for the preservation of archaeologically sensitive layers. It is anticipated that it will be necessary to provide further information about the archaeological potential of the site from field observations, in order to draw up a scheme to mitigate the impact of the proposed residential development on any below-ground archaeological deposits if necessary. -

![Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0520/lullingstone-roman-villa-a-teachers-handbook-revised-380520.webp)

Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 970 SO 031 609 AUTHOR Watson, lain TITLE Lullingstone Roman Villa. A Teacher's Handbook. [Revised]. ISBN ISBN-1-85074-684-2 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 44p. AVAILABLE FROM English Heritage, Education Service, 23 Savile Row, London W1X lAB, England; Tel: 020 7973 3000; Fax: 020 7973 3443; E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: (www.english-heritage.org.uk/). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archaeology; Foreign Countries; Heritage Education; *Historic Sites; Historical Interpretation; Learning Activities; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *England (Kent); English History; Mosaics; *Roman Architecture; Roman Civilization; Roman Empire; Site Visits; Timelines ABSTRACT Lullingstone, in Kent, England, is a Roman villa which was in use for almost the whole period of the Roman occupation of Britain during the fourth century A.D. Throughout this teacher's handbook, emphasis is placed on the archaeological evidence for conclusions about the use of the site, and there are suggested activities to help students understand the techniques and methods of archaeology. The handbook shows how the site relates to its environment in a geographical context and suggests how its mosaics and wall paintings can be used as stimuli for creative work, either written or artistic. It states that the evidence for building techniques can also be examined in the light of the technology curriculum, using the Roman builder activity sheet. The handbook consists of the following sections: -

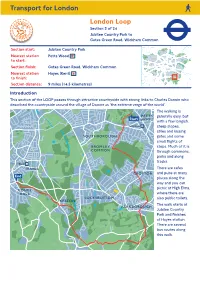

London Loop. Section 3 of 24

Transport for London. London Loop. Section 3 of 24. Jubilee Country Park to Gates Green Road, Wickham Common. Section start: Jubilee Country Park. Nearest station Petts Wood to start: Section finish: Gates Green Road, Wickham Common. Nearest station Hayes (Kent) to finish: Section distance: 9 miles (14.5 kilometres). Introduction. This section of the LOOP passes through attractive countryside with strong links to Charles Darwin who described the countryside around the village of Downe as 'the extreme verge of the world'. The walking is generally easy, but with a few longish, steep slopes, stiles and kissing gates and some small flights of steps. Much of it is through commons, parks and along tracks. There are cafes and pubs at many places along the way and you can picnic at High Elms, where there are also public toilets. The walk starts at Jubilee Country Park and finishes at Hayes station. There are several bus routes along this walk. Continues Continues on next page Directions. To get to the start of this walk from Petts Wood station exit on the West Approach side of the station and turn right at the T-junction with Queensway. Follow the street until it curves round to the left, and carry straight on down Crest View Drive. Take Tent Peg Lane on the right and keep to the footpath through the trees to the left of the car park. After 100 metres enter Jubilee Country Park, and join the LOOP. From the car park on Tent Peg Lane enter the park and at the junction of several paths and go through the gate on the left and follow the metalled path for about 150 metres, then branch left. -

The Earlier Parks Charles I's New Park

The Creation of Richmond Park by The Monarchy and early years © he Richmond Park of today is the fifth royal park associated with belonging to the Crown (including of course had rights in Petersham Lodge (at “New Park” at the presence of the royal family in Richmond (or Shene as it used the old New Park of Shene), but also the Commons. In 1632 he the foot of what is now Petersham in 1708, to be called). buying an extra 33 acres from the local had a surveyor, Nicholas Star and Garter Hill), the engraved by J. Kip for Britannia Illustrata T inhabitants, he created Park no 4 – Lane, prepare a map of former Petersham manor from a drawing by The Earlier Parks today the “Old Deer Park” and much the lands he was thinking house. Carlile’s wife Joan Lawrence Knyff. “Henry VIII’s Mound” At the time of the Domesday survey (1085) Shene was part of the former of the southern part of Kew Gardens. to enclose, showing their was a talented painter, can be seen on the left Anglo-Saxon royal township of Kingston. King Henry I in the early The park was completed by 1606, with ownership. The map who produced a view of a and Hatch Court, the forerunner of Sudbrook twelfth century separated Shene and Kew to form a separate “manor of a hunting lodge shows that the King hunting party in the new James I of England and Park, at the top right Shene”, which he granted to a Norman supporter. The manor house was built in the centre of VI of Scotland, David had no claim to at least Richmond Park.