The Political Economic Context of Syria's Reconstruction: a Prospective in Light of a Legacy of Unequal Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bi-Weekly Update Whole of Syria

BI-WEEKLY UPDATE WHOLE OF SYRIA Issue 5 | 1 - 15 March 2021 1 SYRIA BI-WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT – ISSUE 5 | 1 – 15 MARCH 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. COVID-19 UPDATE ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. COVID-19 STATISTICAL SUMMARY AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL .............................................................................................. 1 1.2. DAILY DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND CUMULATIVE CFR AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL .................................................... 1 1.3. DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND DEATHS AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL ........................................................................... 2 1.4. DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND DEATHS BY GOVERNORATE AND OUTCOME ................................................................. 2 2. WHO RESPONSE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. HEALTH SECTOR COORDINATION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2. NON-COMMUNICABLE DISEASES AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE ................................................................................................ 3 2.3. COMMUNICABLE DISEASE (CD) ....................................................................................................................................... -

“No One's Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in Al-Bayda

HUMAN RIGHTS “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda & Baniyas WATCH “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda and Baniyas Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-62313-0480 Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0480 “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda and Baniyas Maps ................................................................................................................................... i Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

Into the Tunnels

REPORT ARAB POLITICS BEYOND THE UPRISINGS Into the Tunnels The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Rebel Enclave in the Eastern Ghouta DECEMBER 21, 2016 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Baʻath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas. Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas. Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside. However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest. -

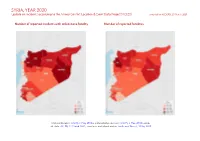

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Syria Crisis Response Annual Report 2013

syria crisis response annual report 2013 UNRWA would like to thank the following donors for their support to the UNRWA Syria Crisis Response Appeal, January-December 2013: • AUSTRALIA • BULGARIA • CZECH REPUBLIC • DENMARK • EC INCLUDING ECHO • FRANCE • GERMANY • GERMANY KFW • HUNGARY • ICELAND • IRELAND © UNRWA 2014 • ITALY About UNRWA • JAPAN UNRWA is a United Nations agency established by the General • KUWAIT Assembly in 1949 and is mandated to provide assistance and • NETHERLANDS protection to a population of some 5 million registered Palestine • NEW ZEALAND refugees. Its mission is to help Palestine refugees in Jordan, • NORWAY Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and the Gaza Strip to achieve their full • SPAIN (INCLUDING LOCAL GOVERNMENTS) potential in human development, pending a just solution to their • SWEDEN plight. UNRWA’s services encompass education, health care, • SWITZERLAND relief and social services, camp infrastructure and improvement, • UK microfinance and emergency assistance. UNRWA is funded • USA almost entirely by voluntary contributions. • CERF • OCHA (ERF) Cover photo: Two boys in an IDP collective shelter in Jaramana • UNICEF camp, Damascus. © Carole al Farah / UNRWA Archives. • AMERICAN FRIENDS OF UNRWA • CAN FOUNDATION (CAJA NAVARRA FOUNDATION), SPAIN • EDUCATION ABOVE ALL FOUNDATION- EDUCATE A CHILD PROGRAM, QATAR • HUMAN APPEAL INTERNATIONAL, UAE • ISLAMIC RELIEF, USA • LES AMIS DE LIBAN À MONACO • QATAR RED CRESCENT SOCIETY • REPSOL FOUNDATION, SPAIN • SAP, MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA • SAUDI COMMITTEE • SOS CHILDREN’S -

Why Are Warm-Water Ports Important to Russian Security?

JEMEAA - FEATURE Why Are Warm- Water Ports Important to Russian Security? The Cases of Sevastopol and Tartus Compared TANVI CHAUHAN Abstract This article aims to examine why Russia’s warm-water ports are so important to Russian security. First, the article defines whatsecurity encompasses in relation to ports. Second, the article presents two case studies: the Crimean port of Sevasto- pol and the Syrian port of Tartus. This article proves that warm-water ports are important to Russian security because they enable Russia to control the sea, proj- ect power, maintain good order, and observe a maritime consensus. Each of these categorical reasons are then analyzed in the Crimean and Syrian context. The re- sults are compared in regional perspective, followed by concluding remarks on what the findings suggest about Russian foreign policy in retrospect, as well as Russian security in the future. Introduction General discourse attribute ports with a binary character: commercial or naval. However, the importance of ports is not limited to those areas alone. Security in the twenty- first century has come to constitute multidimensional relationships, so this article will approach the importance of warm- water ports for security by us- ing the broad concept of maritime security, rather than naval security alone. Previ- ously, the maritime context covered naval confrontations and absolute sea control, but today, scholars have elaborated the maritime environment to include security missions spanning from war and diplomacy to maritime resource preservation, safe cargo transit, border protection from external threats, engagement in security operations, and preventing misuse of global maritime commons.1 Thus, maritime security has crucial links to political, economic, military, and social elements. -

State-Led Urban Development in Syria and the Prospects for Effective Post-Conflict Reconstruction

5 State-led urban development in Syria and the prospects for effective post-conflict reconstruction NADINE ALMANASFI As the militarized phase of the Syrian Uprising and Civil War winds down, questions surrounding how destroyed cities and towns will be rebuilt, with what funding and by whom pervade the political discourse on Syria. There have been concerns that if the international community engages with reconstruction ef- forts they are legitimizing the regime and its war crimes, leaving the regime in a position to control and benefit from reconstruc- tion. Acting Assistant Secretary of State of the United States, Ambassador David Satterfield stated that until a political process is in place that ensures the Syrian people are able to choose a leadership ‘without Assad at its helm’, then the United States will not be funding reconstruction projects.1 The Ambassador of France to the United Nations also stated that France will not be taking part in any reconstruction process ‘unless a political transition is effectively carried out’ and this is also the position of the European Union.1 Bashar al-Assad him- self has outrightly claimed that the West will have no part to play 1 Beals, E (2018). Assad’s Reconstruction Agenda Isn’t Waiting for Peace. Neither Should Ours. Available: https://tcf.org/content/report/assads-recon- struction-agenda-isnt-waiting-peace-neither/?agreed=1. 1 Irish, J & Bayoumy, Y. (2017). Anti-Assad nations say no to Syria recon- struction until political process on track. Available: https://uk.reu- ters.com/article/uk-un-assembly-syria/anti-assad-nations-say-no-to-syria- reconstruction-until-political-process-on-track-idUKKCN1BU04J. -

Download S/2013/735

United Nations A/68/663–S/2013/735 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2013 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-eighth session Sixty-eighth year Agenda item 33 Prevention of armed conflict Identical letters dated 13 December 2013 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the final report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (see annex). I would be grateful if the present final report, the letter of transmittal and its appendices could be brought to the attention of the Members of the General Assembly and of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 13-61784 (E) 131213 *1361784* A/68/663 S/2013/735 Annex Letter of transmittal Having completed our investigation into the allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic reported to you by Member States, and further to the report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (hereinafter, the “United Nations Mission”) on allegations of the use of the chemical weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013 (A/67/997-S/2013/553), we have the honour to submit the final report of the United Nations Mission. To date, 16 allegations of separate incidents involving the use of chemical weapons have been reported to the Secretary-General by Member States, including, primarily, the Governments of France, Qatar, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

IMPRISONED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS SYRIA Amnesty

IMPRISONED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS SYRIA Amnesty International is deeply concerned at the continued detention without charge or trial of 90 doctors, dentists and veterinarians who were arrested in 1980 following widespread agitation in Syria for political reforms, including an end to the State of Emergency, in force since 1963. Despite repeated requests for information on those detained, the government has failed to provide information on their whereabouts and well-being. Background The main provisions of the Syrian constitution which specify the freedoms of the citizen remain suspended under the terms of Military Order 2 of 17 March 1963 declaring a State of Emergency. The State of Emergency Law gives the security forces wide powers to arrest and administratively detain anyone suspected of "endangering security and public order". The Martial Law Governor (the Prime Minister), or his deputy, is empowered to delegate to anyone the powers to administratively detain, investigate, or restrict the freedom of persons in respect to meetings, residence, travel and passage. These powers have been delegated to the security forces and in practice have been used in such a way as to result in thousands of arbitrary arrests. The vast majority of political detainees in Syria are held without charge or trial, many for long periods. Families are given no official notification of the arrest, place of detention or subsequent movements of detainees and must obtain such information through their own efforts. Reports of torture and ill-treatment of detainees are common. Such treatment is facilitated by the extensive powers of arbitrary arrest and detention conferred on the security forces which enables them to hold detainees for indefinite periods without any external supervision of their cases. -

Syria's Missing Narratives

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford Syria’s Missing Narratives by Basma Atassi Hilary and Trinity Terms 2015 Sponsors: Said Foundation and Asfari Foundation 1 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my thanks to the Asfari Foundation, the Said Foundation and the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for selecting me as a fellow and giving me the opportunity to study in one of the top educational institutions in the world. This fellowship has been a once in a life-time opportunity for me. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr James Painter for his meticulous supervision and enthusiastically engaging conversations over my thesis. My utmost gratitude goes to my father, who, before passing away earlier this year, told me that I can be anyone I aspire to be; my mother for the unconditional love and support; and Saleh, my loving husband for his patience and encouragement. 2 Table of contents: 1. Introduction 2. Syria and the media 3. Civil Society/Local actors 4. Hungry for peace 5. War journalism 6. Peace Journalism Model 7. Case study of Barzeh 8. Conclusion Appendix Media Coverage of Barzeh Bibliography 3 1. Introduction “There is no voice louder than the voice of the battle. Everything for the sake of the battle… Opinions are oppressed for the sake of the battle.” Egyptian Poet Ahmed Fouad Nagm The conflict in Syria is the worst conflict since WWII. There are at least two dozen countries involved in the fighting there. The humanitarian and security situation continue to deteriorate, with the death toll now topping 500,000 and over half of the population displaced.