We Looks Like Men-Er-War'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Report of the Battle of the Crater, 30 July 1864

Holding the Line A Preliminary Report of The Battle of the Crater 30 July 1864 Adrian Mandzy, Ph. D. Michelle Sivilich, Ph. D. Benjamin Lewis Fitzpatrick, Ph. D. Dan Sivilich Floyd Patrick Davis Kelsey P. Becraft Dakota Leigh Goedel Jeffrey A. McFadden Jessey C. Reed Jaron A. Rucker A PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE SURVEY OF THE BATTLE OF THE CRATER, 30 JULY 1864 By Adrian Mandzy, Ph.D., Michelle Sivilich, Ph. D., Floyd Patrick Davis, Kelsey P. Becraft, Dakota Leigh Goedel, Jeffrey A. McFadden, Jessey C. Reed, and Jaron A. Rucker With a Contributions by Daniel Sivilich and Dr. Benjamin Lewis Fitzpatrick Report prepared for the Northeast Region Archeology Program National Park Service 115 John Street, 4th Floor Lowell, Massachusetts 01852-1195 _______________________________ Adrian Mandzy Principal Investigator ARPA Permit 2014.PETE.01 2 Abstract In March 2015, faculty and students from Morehead State University’s History program, along with members of the Battlefield Restoration and Archeological Volunteer Organization (BRAVO) conducted a survey of The Crater Battlefield. Fought on 30 July 1864, during the Siege of Petersburg, the Battle of the Crater, according to the National Park Service, is one of the most important events of the Civil War. The participation of African-American troops in the battle and the subsequent execution of black prisoners highlights the racial animosities that were the underpinning causes of this conflict. The goal of this project is to document the level of integrity of any archaeological resources connected with this field of conflict and to examine how far the Union troops advance beyond the mouth of the Crater. -

Walt Whitman on Brother George and His Fifty-First New York Volunteers: an Uncollected New York Times Article

Volume 18 Number 1 ( 2000) Special Double Issue: pps. 65-70 Discoveries Walt Whitman on Brother George and His Fifty-First New York Volunteers: An Uncollected New York Times Article Martin Murray ISSN 0737-0679 (Print) ISSN 2153-3695 (Online) Copyright © 2000 Martin Murray Recommended Citation Murray, Martin. "Walt Whitman on Brother George and His Fifty-First New York Volunteers: An Uncollected New York Times Article." Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 18 (Summer 2000), 65-70. https://doi.org/10.13008/2153-3695.1635 This Discovery is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walt Whitman Quarterly Review by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. W ALTWHITMAN ON BROTHER GEORGE AND HIS FIFTY-FIRST NEWYORKVOLUNTEERS: AN UNCOLLECTED NEW YORK TIMES ARTICLE MARTIN G. MURRAY WALT WHITMAN'S CML WAR journalism falls neatly into two categories: brother George, and everything else. While the latter category encom passes a potpourri of topics, from hospital visits to Lincoln's inaugura tion to the weather in Washington, D.C., the former category focuses tightly on the military valor of George Washington Whitman and his Fifty-first New York Volunteers. To date, scholars have collected five such newspaper articles pertaining to George's regiment, beginning with the January 5, 1863, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and ending with the August 5, 1865, Brooklyn Daily Union. l To these can be added a sixth, un signed article published on January 24, 1865, in the New York Times. -

Siege of Petersburg

Seige Of Petersburg June 9th 1864 - March 25th 1865 Siege Of Petersburg Butler”s assault (June 9) While Lee and Grant faced each other after Cold Harbor, Benjamin Butler became aware that Confederate troops had been moving north to reinforce Lee, leaving the defenses of Petersburg in a vulnerable state. Sensitive to his failure in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, Butler sought to achieve a success to vindicate his generalship. He wrote, "the capture of Petersburg lay near my heart." Petersburg was protected by multiple lines of fortifications, the outermost of which was known as the Dimmock Line, a line of earthworks 10 miles (16 km) long, east of the city. The 2,500 Confederates stretched thin along this defensive line were commanded by a former Virginia governor, Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise. Butler”s plan was formulated on the afternoon of June 8, 1864, calling for three columns to cross the Appomattox and advance with 4,500 men. The first and second consisted of infantry from Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore”s X Corps and U.S. Colored Troops from Brig. Gen. Edward W. Hinks”s 3rd Division of XVIII Corps, which would attack the Dimmock Line east of the city. The third was 1,300 cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. August Kautz, who would sweep around Petersburg and strike it from the southeast. The troops moved out on the night of June 8, but made poor progress. Eventually the infantry crossed by 3:40 a.m. on June 9 and by 7 a.m., both Gillmore and Hinks had encountered the enemy, but stopped at their fronts. -

Route 10 (Bermuda Triangle Road to Meadowville Road) Widening Project VDOT Project Number 0010-020-632, (UPC #101020) (VDHR File No

Route 10 (Bermuda Triangle Road to Meadowville Road) Widening Project VDOT Project Number 0010-020-632, (UPC #101020) (VDHR File No. 1995-2174) Phase I Architectural Identification Survey Chesterfield County, Virginia Phase I Archaeological Identification Survey for the Route 10 Project (Bermuda Triangle to Meadowville) Chesterfield County, Virginia VDOT Project No. 0010-020-632, UPC #101020 Prepared for: Prepared for: Richmond District Department of Transportation 2430VDOT Pine Richmond Forest Drive District Department of Transportation 9800 Government Center Parkway Colonial2430 Heights, Pine Forest VA Drive23834 9800 Government Center Parkway Chesterfield, Virginia 23832 Colonial804 Heights,-524-6000 Virginia 23834 Chesterfield, VA 23832 804-748-1037 Prepared by: March 2013 Prepared by: McCormick Taylor, Inc. North Shore Commons A 4951 McCormickLake Brook Drive, Taylor Suite 275 NorthGlen ShoreAllen, VirginiaCommons 23060 A 4951 Lake Brook Drive, Suite 275 Glen Allen, VA 23060 May 2013 804-762-5800 May 2013 Route 10 (Bermuda Triangle Road to Meadowville Road) Widening Project VDOT Project Number 0010-020-632, (UPC #101020) (VDHR File No. 1995-2174) Phase I Architectural Identification Survey Phase I ArchaeologicalChesterfield County,Identification Virginia Survey for the Route 10 Project (Bermuda Triangle to Meadowville) Chesterfield County, Virginia VDOT Project No. 0010-020-632, UPC #101020 Prepared for: Prepared for: Richmond District Department of Transportation 2430VDOT Pine Richmond Forest Drive District Department of Transportation 9800 Government Center Parkway Colonial2430 Heights, Pine Forest VA Drive23834 9800 Government Center Parkway Chesterfield, Virginia 23832 Colonial804 Heights,-524-6000 Virginia 23834 Chesterfield, VA 23832 804-748-1037 Prepared by: March 2013 Prepared by: McCormick Taylor NorthMcCormick Shore Commons Taylor, Inc. -

Ambrose Burnside, the Ninth Army Corps, and the Battle of Ps Otsylvania Court House Ryan T

Volume 5 Article 7 4-20-2015 Ambrose Burnside, the Ninth Army Corps, and the Battle of pS otsylvania Court House Ryan T. Quint University of Mary Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Quint, Ryan T. (2015) "Ambrose Burnside, the Ninth Army Corps, and the Battle of potsS ylvania Court House," The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era: Vol. 5 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe/vol5/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ambrose Burnside, the Ninth Army Corps, and the Battle of pS otsylvania Court House Abstract The ghfi ting on May 12, 1864 at Spotsylvania Court House evokes thoughts of the furious combat at the Bloody Angle. However, there is another aspect of the fighting on May 12, that is, incidentally, at another salient. The then-independent command of Ambrose Burnside’s Ninth Corps spent the day fighting on the east flank of the Mule Shoe, and charging against the Confederate right flank at Heth’s Salient. This paper has two parts: the first half analyzes the complexities and problems of Burnside’s return to the Eastern Theater since his disastrous defeat at Fredericksburg in 1862, starting in April 1864 and culminating with the opening moves of the Overland Campaign. -

“GITTIN STUFF” the Impact of Equipment Management, Supply & Logistics on Confederate Defeat

“GITTIN STUFF” The Impact of Equipment Management, Supply & Logistics on Confederate Defeat BY FRED SETH, CPPM, CF, HARBOUR LIGHTS CHAPTER “They never whipped us, Sir, unless they were four to one. had been captured. For four years they had provided equipment and supplies from If we had had anything like a fair chance, or less disparity of Europe to support the Confederacy and its numbers, we should have won our cause and established our armies. Since the beginning of the war, independence.” UNKNOWN VIRGINIAN TO ROBERT E. LEE.1 Wilmington, North Carolina had been a preferred port of entry for blockade-run- ners because Cape Fear provided two entry the destruction or capture of factories and channels, which gave ships a greater oppor- PREFACE farms in the Deep South and Richmond. tunity for escape and evasion. Also, rail fter defeat in the Civil War, known by The lack of rations at Amelia Court House, lines ran directly from Wilmington to A some in the South as “The War of which has been called the immediate cause Richmond and Atlanta.4 Northern Aggression,” Southerners were in of Lee’s surrender, is examined in detail. By the fall of 1864, Wilmington was a quandary regarding their willingness for Most importantly, the article addresses how one of the most important cities in the war. As discussed in the first article of this the inability of its leaders to conduct pro- Confederacy – it was the last operating series, the North had the overwhelming ductive logistics, equipment, and supply port. Confederate armies depended on advantage in industrial capability and man- management led to the decline and ulti- Wilmington for lead, iron, copper, steel, power. -

The Antietam and Fredericksburg

North :^ Carolina 8 STATE LIBRARY. ^ Case K3€X3Q£KX30GCX3O3e3GGG€30GeS North Carolina State Library Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/antietamfredericOOinpalf THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG- Norff, Carof/na Staie Library Raleigh CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR.—Y. THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG BY FEAISrCIS WmTHEOP PALFEEY, BREVET BRIGADIER GENERAL, U. 8. V., AND FORMERLY COLONEL TWTENTIETH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY ; MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETF, AND OF THE MILITARY HIS- TORICAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEE'S SONS 743 AND 745 Broadway 1893 9.73.733 'P 1 53 ^ Copyright bt CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1881 PEEFAOE. In preparing this book, I have made free use of the material furnished by my own recollection, memoranda, and correspondence. I have also consulted many vol- umes by different hands. As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both. By far the lar- gest assistance I have had, has been derived from ad- vance sheets of the Government publication of the Reports of Military Operations During the Eebellion, placed at my disposal by Colonel Robert N. Scott, the officer in charge of the War Records Office of the War Department of the United States, F, W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE List of Maps, ..«.••• « xi CHAPTER I. The Commencement of the Campaign, .... 1 CHAPTER II. South Mountain, 27 CHAPTER III. The Antietam, 43 CHAPTER IV. Fredeeicksburg, 136 APPENDIX A. Commanders in the Army of the Potomac under Major-General George B. -

Muster Roll Exhibits the True State of Col

t-1o P MUSTER EOLL of Field and Staff in the 51st Regiment of New York Volunteers, commanded by Colonel Edward Ferrero, 'i : called into the service of the United States by E. D. Morgan, Governor, from the day of , 186—, (date of this Jg ; for the term of , unless sooner discharged. VALUATION IN JOINED EOE DUTY AND ENROLLED. TRAVELING. OF— REMAEKS. NAMES. DOLLARS, 1. Every man whosenameis on this roll mnst PRESENT AND ABSENT. place place RANK. AGE To From he accounted for on the next master roll. hi By whom of rendez of disch'ge Horse The exchangeof men,hy 1-H (Privates in alphabetical equip- snbstitntion. andthe order.) When. Where. enrolled. Period. vous, No. home, No. exchanging, swapping or loaning of horses, PS of miles. of miies. aftermusterinto service,arestrictly forbidden. pl h) Edward Ferrero Sept. Colonel . 31 13 New York Gen. Yates $225 $80 Mustered in U. S. service by 1861 1861 Capt. Larned Oct. 14 tz Robert B. Potter Major • . 32 Oct. 12 do Col. Ferrero 200 65 do do 14 PJ in Augustus 3. Dayton . Adjutant Aug. Brooklyn . 32 16 Samuel H. Sims . do do 2 i-3 >~ Ephraim W. Buck. Surgeon Sept. 29 20 New York E. Ferrero 150 70 do do 4 hi Pi Charles W. Torrey Asst. Surg 25 Oct. 14 clo do do do 14 Daniel W. Horton. Qr. Master Aug. 25 31 do do clo do 4 Orlando N. Benton Chaplain . 34 Oct. 15 do do 200 45 do do 15 PS XOX-COMMISSIOXED STAFF. PS George W. Whitman Srgt. -

Captain Flashback #7

CAPTAIN FLASHBACK A fanzine composed for the 396th distribution of the Turbo-Charged Party-Animal Amateur Press A PERFECT DAY Association, from the joint membership of Andy IN THE BLOODY LANE th Hooper and Carrie Root, residing at 11032 30 Ave. Paying Our Respects in Hagerstown NE Seattle, WA 98125. E-mail Andy at and at the Field of the Antietam [email protected], and you may reach Carrie at [email protected]. This is a Drag Bunt Press by Andy Hooper Production, completed on 6/21/2019. For the last several years, Carrie and I have enjoyed a special excursion on the Monday CAPTAIN FLASHBACK is devoted to old fanzines, following the end of Corflu, the annual monster movies, garage bands and other fascinating phenomena of the 20th Century. Issue #7 begins with convention for fanzine fans. We shifted our the last day our recent trip to New York and attention to the day after the con following the Maryland, including a visit to Hagerstown and the Richmond, Virginia Corflu in 2014, before Antietam National Battlefield Park. which we had visited Monticello and the battlefield at Petersburg. We had a great time, . And after the usual lengthy comments on the but by flying out the day after the convention, previous mailing, the I REMEMBER ENTROPY Department presents an article on one memorable we missed one of our last opportunities to spend program at the first Corflu in January, 1984, a day with the late Art Widner; and when Corflu published in THE TWILTONE ZONE ’85 #1, and came to Chicago in 2016, we made sure to be written by Cheryl Cline, one of Corflu’s “Founding available for museum excursions and other post- Mothers.” Plus Letters of Comment! convention fun. -

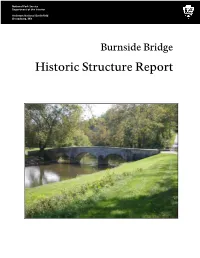

Burnside Bridge FINAL HSR.Pdf

National Park Service Department of the Interior Antietam National Battlefield Sharpsburg, MD Burnside Bridge Historic Structure Report The historic structure report presented here exists in two formats. A traditional, printed version is available for study at Antietam National Battlefield, the National Capital Regional Office of the NPS, Denver Service Center of the NPS, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, the historic structure report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps.gov for more information. Antietam National Battlefield Burnside Bridge Historic Structure Report February 2017 for Antietam National Battlefield Sharpsburg, MD by Jennifer Leeds NCPE Historical Architect Intern & Rebecca Cybularz Historical Architect Historic Preservation Training Center Office of Learning and Development Workplace, Relevancy, and Inclusion (WASO) National Park Service Frederick, MD Approved by: _________________________________________________________________ Superintendent, Antietam National Battlefield Date This page intentionally blank. Table of Contents Project Team 1 Executive Summary 3 Administrative Data 7 List of Abbreviations 10 List of Figures 11 List of Tables 12 Part 1 Developmental History Historical Background and Context 15 Chronology of Development and Use 29 Architectural Descriptions 59 Physical Description 60 Character-Defining Features 69 Condition Assessment 75 Part 2 Treatment and Use Requirements for Treatment and Use -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Battle of Antietam

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 1-1-1966 Battle of Antietam James Edward Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Martin, James Edward, "Battle of Antietam" (1966). Plan B Papers. 484. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/484 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATTLE OF ANTI~TAM (TITLE) BY James Edward Martin B. s. in ~a., Eastern Illinois University, 1963 PLAN B PAPER SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE. IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE Civil War Se~inar IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED . ..•. / .¥/ l 0 DATE ADVISER DATE DEPARTMENT HEAD Battle of Antietam Never before or since in American History was so much blood shed on a single day as on September 17, 1862, at the battle of Antietam. For the clarification of the reader, the battle of Antiteam bears a double name--the troops of the North referred to the battle as Antietam while their counterparts referred to the engagement as Sharpsburg. Regardless as to its name, this historic battle was the turning point of the Civil War and the high tide of the Confederacy.