Nowcasting the Great Recession in Alternative Economic Indicators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBO's Economic Forecasting Record

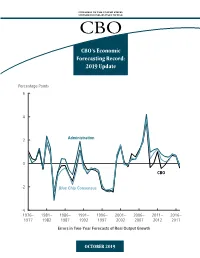

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE CBO’s Economic Forecasting Record: 2019 Update Percentage Points 6 4 2 Administration 0 CBO -2 Blue Chip Consensus -4 1976– 1981– 1986– 1991– 1996– 2001– 2006– 2011– 2016– 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012 2017 Errors in Two-Year Forecasts of Real Output Growth OCTOBER 2019 At a Glance In this report, the Congressional Budget Office assesses its two-year and five-year economic forecasts and compares them with forecasts of the Administration and the Blue Chip consensus. Measures of Quality. CBO focuses on three measures of forecast quality— mean error, root mean square error, and two-thirds spread of errors—that help the agency identify the centeredness (that is, the opposite of statistical bias), accuracy, and dispersion of its forecast errors. The Quality of CBO’s Forecasts. CBO’s forecasts of most economic variables are, on average, too high by small amounts. As measured by the root mean square error, its two-year forecasts of most variables are not appreciably more accurate than its five-year forecasts. CBO is least accurate in forecasting growth of wages and salaries. Comparison With Other Forecasts. For the most part, CBO’s and the Administration’s forecasts exhibit similar degrees of centeredness, but CBO’s forecasts are slightly more accurate and have smaller two-thirds spreads. For all three quality measures, CBO’s forecasts are roughly comparable to the Blue Chip consensus forecasts. Sources of Forecast Errors. All forecasters failed to anticipate certain key economic developments, resulting in significant forecast errors. The main sources of those errors are turning points in the business cycle, changes in labor productivity trends and crude oil prices, the persistent decline in interest rates, the decline in labor income as a share of gross domestic product, and data revisions. -

Facts and Challenges from the Great Recession for Forecasting and Macroeconomic Modeling

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FACTS AND CHALLENGES FROM THE GREAT RECESSION FOR FORECASTING AND MACROECONOMIC MODELING Serena Ng Jonathan H. Wright Working Paper 19469 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19469 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2013 We are grateful to Frank Diebold and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Kyle Jurado provided excellent research assistance. The first author acknowledges financial support from the National Science Foundation (SES-0962431). All errors are our sole responsibility. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w19469.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Serena Ng and Jonathan H. Wright. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Facts and Challenges from the Great Recession for Forecasting and Macroeconomic Modeling Serena Ng and Jonathan H. Wright NBER Working Paper No. 19469 September 2013 JEL No. C22,C32,E32,E37 ABSTRACT This paper provides a survey of business cycle facts, updated to take account of recent data. Emphasis is given to the Great Recession which was unlike most other post-war recessions in the US in being driven by deleveraging and financial market factors. -

Analysis of Growth Rates in Different Regimes of Pakistan: Distribution and Forecasting Anwar Hussain ∗ & Naila Nazir ∗∗

Analysis of Growth Rates in Different Regimes of Pakistan: Distribution and Forecasting Anwar Hussain ∗ & Naila Nazir ∗∗ Abstract The present study aims to analyze the growth rate distribution pattern in different regimes of Pakistan and also forecasts the growth rates of agricultural, industrial, services and GDP growth rates in Pakistan. The study uses secondary data ranging from 1956 to 2011. The data from 1956 to 2000 has been obtained from State Bank of Pakistan and from 2001 to 2011 from Economic Survey of Pakistan. For the analysis of the regime-wise distribution of growth rates, the Gini-coefficient and Lorenz curve are used. While for forecasting the growth rates, moving average forecast and exponential smoothing method have been used. The findings revealed that the Gini-coefficients for agriculture, industrial, services and GDP growth rates were 0.161453, 0.214199, 0.147940 and 0.112955. The Lorenz curve also suggests equality between selected growth rates regime-wise. The moving average forecasts for agriculture, industrial, services sector and GDP growth rates in the year 2012 is 1.7%, 2.7%, 2.9% and 3.1% respectively for the year 2012. According to the exponential smoothing method these growth rates in the year 2012 are projected to be 1.9%, 3.1%, 3.8% and 3.3% respectively. Looking over the growth distribution pattern, there is a need to take revolutionary steps and big push to boost the macroeconomic variables performance in Pakistan. Based on the forecasting results, the services sector may decline in next year, which needs to be focused on. Key words : Growth Rates, Distribution, Lorenz Curve, Gini-coefficient, Forecasting, Moving Average, Exponential Smoothing. -

Internet Search Behavior As an Economic Forecasting Tool

Internet Search Behavior as an Economic Forecasting Tool: The Case of Inflation Expectations1 Giselle Guzmán, Ph.D., FRM Economic Alchemy LLC Draft, Preliminary and Incomplete This Version: November 29, 2011 1 A previous version of this paper circulated under the title “An Inflation Expectations Horserace,” and was submitted in partial fulfillment of the Ph.D. degree in Finance and Economics at Columbia University. Contact information: [email protected]. I would like to thank Lawrence Klein, Joseph Stiglitz, Hal Varian, Marshall Blume, Marc Giannoni, Charles Jones, and Lawrence Glosten for their insights and guidance. Thanks also to Randy Moore, William Dunkelberg, Richard Curtin, Lynn Franco, and Dennis Jacobe for generously providing data. All equations estimated with EViews Version 6 for Windows PC by Quantitative Micro Software, LLC. Any errors are solely my own. 1 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2004598 Internet Search Behavior as an Economic Forecasting Tool: The Case of Inflation Expectations Abstract: This paper proposes a measure of real-time inflation expectations based on metadata, i.e., data about data, constructed from internet search queries performed on the search engine Google. The forecasting performance of the Google Inflation Search Index (GISI) is assessed relative to 37 other indicators of inflation expectations – 36 survey measures and the TIPS spread. For decades, the academic literature has focused on three measures of inflation expectations: the Livingston Survey, Survey of Professional Forecasters, and the Michigan Survey. While useful in developing models of forecasting inflation, these low frequency measures appear anachronistic in the modern era of higher frequency and real-time data. -

Lessons for Forecasting Unemployment in the US

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of ATLANTA WORKING PAPER SERIES Lessons for Forecasting Unemployment in the United States: Use Flow Rates, Mind the Trend Brent Meyer and Murat Tasci Working Paper 2015-1 February 2015 Abstract: This paper evaluates the ability of autoregressive models, professional forecasters, and models that incorporate unemployment flows to forecast the unemployment rate. We pay particular attention to flows-based approaches—the more reduced-form approach of Barnichon and Nekarda (2012) and the more structural method in Tasci (2012)—to generalize whether data on unemployment flows are useful in forecasting the unemployment rate. We find that any approach that considers unemployment inflow and outflow rates performs well in the near term. Over longer forecast horizons, Tasci (2012) appears to be a useful framework even though it was designed to be mainly a tool to uncover long-run labor market dynamics such as the “natural” rate. Its usefulness is amplified at specific points in the business cycle when the unemployment rate is away from the longer-run natural rate. Judgmental forecasts from professional economists tend to be the single best predictor of future unemployment rates. However, combining those guesses with flows-based approaches yields significant gains in forecasting accuracy. JEL classification: E24; E32; J64; C53 Key words: unemployment forecasting, natural rate, unemployment flows, labor market search The authors thank participants of the Midwest Economic Association Meetings (Evanston, 2013). The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland and Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System. Any remaining errors are the authors’ responsibility. -

Forecasting the United States Gross Domestic Product with a Neural Network Milam Aiken the University of Mississippi

Journal of International Information Management Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 7 2000 Forecasting the United States gross domestic product with a neural network Milam Aiken The University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/jiim Part of the Management Information Systems Commons Recommended Citation Aiken, Milam (2000) "Forecasting the United States gross domestic product with a neural network," Journal of International Information Management: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/jiim/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Information Management by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aiken: Forecasting the United States gross domestic product with a neura Journal of International Information Management Forecasting the US Gross Domestic Product Forecasting the United States gross domestic product with a neural network Milam Aiken The University oi Mississippi ABSTIU»ICT Forecasting the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the United States is one of many esti mates to predict the economic health of the countr)>. Current forecasting techniques use consen sus estimates of experts, econometric models, or other statistical methods. Relatively little re search has been devoted to how artificial neural networks may improve these forecasts, how ever. This paper describes how a neural network using leading economic indicator data pre dicted annual GDP percentage changes one year into thefiiture more accurately than compet ing techniques over a ten-year period. INTRODUCTION Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is that part of Gross National Product (GNP) attributed to labor and property located in the United States. -

Economic Theory and Forecasting

Economic Theory and Forecasting Occasionally this Review publishes articles of a more technical nature. These articles result from basic research efforts of staff economists. It!0dUC1.jUii by the Department of Commerce in Business Cycle Developments. This technique consists of examining a wide range of economic data from previous business I HE ECONOMIC FORECASTS for 1967 have cycles to discover those time series which typically been duly recorded and only await the passage of show peaks and troughs before peaks and troughs time to see how accurate they were. This article does are observed in general business conditions. not attempt to add an additional forecast to those al- ready made. Rather, it specifies some of the common The leading indicators approach is widely reported underlying assumptions or theories which major and discussed in the financial press. In the December groups of forecasters accept and which they implicit- 1966 issue of Business Cycle Developments (which pre- ly or explicitly take into account in constructing a sented the best information then available, when most forecast. forecasts of 1967 were being completed), the leading indicators were giving conflicting evidence about the It is hoped that this review of forecasting as- future. A sampling of leading indicators published in sumptions will help clarify some of the differences the December issue is presented in the accompanying which separate those who forecast a substantial de- table. Some indicators showed continued expansion, cline in the growth of gross national product (GNP) others had turned down, and many were indeter- in 1967, with a resulting increase in unemployment, minate. -

Forecasting Local Inflation with Global Inflation: When Economic Theory Meets the Facts*

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper No. 235 http://www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/institute/wpapers/2015/0235.pdf Forecasting Local Inflation with Global Inflation: When Economic Theory Meets the Facts* Roberto Duncan Enrique Martínez-García Ohio University Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas April 2015 Abstract This paper provides both theoretical insight as well as empirical evidence in support of the view that inflation is largely a global phenomenon. First, we show that inflation across countries incorporates a significant common factor captured by global inflation. Second, we show that in theory a role for global inflation in local inflation dynamics emerges over the business cycle even without common shocks, and under flexible exchange rates and complete international asset markets. Third, we identify a strong "error correction mechanism" that brings local inflation rates back in line with global inflation which explains the relative success of inflation forecasting models based on global inflation (e.g., Ciccarelli and Mojon (2010). Fourth, we argue that the workhorse New Open Economy Macro (NOEM) model of Martínez-García and Wynne (2010) can be approximated by a finite- order VAR and estimated using Bayesian techniques to forecast domestic inflation incorporating all relevant linkages with the rest of the world. This NOEM-BVAR provides a tractable model of inflation determination that can be tested empirically in forecasting. Finally, we use pseudo-out-of-sample forecasts to assess the NOEM-BVAR at different horizons (1 to 8 quarters ahead) across 17 OECD countries using quarterly data over the period 1980Q1-2014Q4. In general, we find that the NOEM-BVAR model produces a lower root mean squared prediction error (RMSPE) than its competitors—which include most conventional forecasting models based on domestic factors and also the recent models based on global inflation. -

Our Consensus Future: the Lay of the Land in 2025

perspectives Our Consensus Future: The Lay of the Land in 2025 Mark Thirlwell S e p t e m b e r 2 0 1 0 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. Our consensus future: The lay of the land in 2025 1 Mark Thirlwell The perils of forecasting The recent financial crisis is a powerful reminder of how bad we are at forecasting. I suspect that nearly every analyst falls into at least one of three camps: (1) those who didn’t see any crisis coming; (2) those who were in fact expecting a crisis, but were expecting either a different crisis from the one we got, or were expecting a particular aspect of that crisis, rather than the whole shocking package; (3) and those who regularly forecast crises that have failed to materialise, but who got lucky this time. -

Machine Learning Methods for Inflation Forecasting in Brazil

Machine learning methods for inflation forecasting in Brazil: new contenders versus classical models Gustavo Silva Araujo y Wagner Piazza Gaglianone z February 19, 2020 Abstract We conduct an extensive out-of-sample forecasting exercise, across a variety of machine learning techniques and traditional econometric models, with the objective of building accurate forecasts of the Brazilian consumer prices inflation at multiple horizons. A large database of macroeconomic and financial variables is employed as input to the competing methods. The results corroborate recent findings in favor of the nonlinear automated procedures, indicating that machine learning algorithms (in particular, random forest) can outperform traditional forecasting methods in terms of mean-squared error. The main reason is that some machine learning methods can yield a sizeable reduction in the forecast bias, while keeping the forecast variance under control. As result, forecast accuracy can be improved over traditional inflation forecasting models. These findings offer a valuable contribution to the field of macroeconomic forecasting, and provide alternative methods to the usual statistical models often based on linear statistical relationships. Keywords: Machine Learning; Inflation; Forecast. JEL Classification: C14; C15; C22; C53; C55; E17; E31. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Banco Central do Brasil. We are especially grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions given by Marcelo Antonio T. de Aragão, Jorge Henrique de Frias Barbosa, Vicente da Gama Machado, Marcelo C. Medeiros, Euler Pereira G. de Mello and André Minella. We also benefited from comments given by the seminar participants at the 18th ESTE - Time Series and Econometrics Meeting (Gramado, September 2019) and the IV Workshop da Rede de Pesquisa do Banco Central do Brasil (Brasília, November 2019). -

Economic Forecasting: Some Lessons from Recent Research

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK WORKING PAPER SERIES ECB EZB EKT BCE EKP WORKING PAPER NO. 82 ECONOMIC FORECASTING: SOME LESSONS FROM RECENT RESEARCH BY DAVID F. HENDRY AND MICHAEL P. CLEMENTS October 2001 EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK WORKING PAPER SERIES WORKING PAPER NO. 82 ECONOMIC FORECASTING: SOME LESSONS FROM RECENT RESEARCH BY DAVID F. HENDRY AND MICHAEL P. CLEMENTS* October 2001 * Financial support from the U.K. Economic and Social Research Council under grant R000233447 is gratefully acknowledged. We are indebted to participants at the ECB Conference on Forecasting Techniques for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Computations were performed using PcGive and the Gauss programming language,Aptech Systems, Inc.,Washington.This paper has been presented at the ECB workshop on ‘Forecasting Techniques’, held in September 2001. © European Central Bank, 2001 Address Kaiserstrasse 29 D-60311 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 16 03 19 D-60066 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone +49 69 1344 0 Internet http://www.ecb.int Fax +49 69 1344 6000 Telex 411 144 ecb d All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank. ISSN 1561-0810 Contents Abstract 4 Non technical summary 5 1 Introduction 6 2 Background 7 2.1 The failure of ‘optimality theory’ 8 3 A more viable framework 9 3.1 A forecast-error taxonomy 10 4 ‘Principles’ based on empirical -

An Overview of Economic Forecasting 1

AN OVERVIEW OF ECONOMIC FORECASTING 1 CHAPTER ONE An Overview of Economic Forecasting Michael P. Clements and David F. Hendry 1.1. INTRODUCTION The chapters of this Companion address a wide range of issues and approaches to economic forecasting. We overview its material in terms of 11 key questions that might fruitfully be asked of any practical venture, but here specifically concern forecasting.1 1 What is a forecast? 2What can be forecast? 3 How confident can we be in forecasts? 4 How is forecasting done generally? 5 How is forecasting done by economists? 6 How can one measure the success or failure of forecasts? 7 How does one analyze the properties of forecasting methods? 8 What special data features matter most? 9 What are the main problems? 10 Do these problems have potential solutions? 11 What is the future of economic forecasting? Some of these questions can be dealt with quickly and are not specifically addressed by any of the contributors, while others provide the subject matter for several chapters. Moreover, several chapters relate to a number of the questions. To set the scene, the first part of this overview provides preliminary remarks in CTEC01 1 21/11/2001, 5:40 PM 2 M.P. CLEMENTS AND D.F. HENDRY response to each question. The second part of the overview then summarizes each chapter in relation to these 11 questions. It is hoped that organizing the Companion in this way will be helpful to the nonspecialist reader. The questions we ask, and the answers that are provided here, require no foreknowledge of the subject, and should allow the reader to dip in at will, without approaching the material in any particular order.