Tng2 Article.Pdf (1.305Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 21st September 2016 Newsletter #140 By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan RIKEY DID the Vodafone Warriors get hammered at the weekend. The constant theme was that we Cneed a player clearout. That is hardly groundbreaking stuff, but what was, was that players were named. Hugh McGahan singled out Manu Vatuvei and Ben Matulino, arguing both had failed to live up their status as two of our highest paid players. The former Kiwi captain said Warriors coach Stephen Kearney could make a mark by showing the pair the door, and proving to the others that poor performances won't be tolerated. “Irrespective of his standing, Manu Vatuvei has got to go,” McGahan told Tony Veitch. “And again, irre- spective of his standing, Ben Matulino has got to go. They have underperformed. If you're going to make an impact I'd say that's probably the two players that you would look at.” Bold stuff, and fair play to the man, he told it like he saw it. Kearney, on the other hand, clearly doesn’t see it the same way, since he named both in the Kiwis train-on squad, and while he acknowledged they had struggled this year, he backed himself to get the best out of them. In fact he went further, he said it was his job. “That's my responsibility as the coach, to get the individuals in a position so they can go out and play their best. -

Wellington Women's Rugby League Representative Trial

Welcome to “PASS IT ON…” Wellington Rugby Leagues enewsletter for 2010. The idea of “PASS IT ON…” is that you do just that and forward it to as many people as you can, who then forward it to as many people as they can. The more people we can tell about the World of Wellington Rugby League the better!!! Message from Dingo Where is the rain? No doubt we will all be crying out for it to go away in the months ahead but it would be great to get a good dumping in the next week or so just to soften the fields a bit and get the grass growing again. That aside wasn’t it fantastic to see junior footy get underway last weekend with lots of supporters around the grounds in the sunshine and heaps of kids out there enjoying throwing the ball around. Our junior numbers are growing and that is a testament to the hard workers in all our local clubs. Parents, coaches and volunteers, sometimes one in the same, are the lifeblood of our game and I thank you all for your commitment to making sure our kids enjoy the great game. At the senior level Porirua again lead the way in premiers with Petone, University, Wainuiomata and Randwick bunched in behind and all capable of knocking off the premiers on their day. St George, Te Aroha and Upper Hutt are all working hard without much success and will need considerable improvement to challenge the 5 sides above them. Premier reserves see University and Randwick leading the way both undefeated, their clash this week should see an outright leader. -

Mad Butcher Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch’s Mad Butcher Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 7 May 2015 Newsletter #71 To subscribe or unsubscribe email: [email protected] Kiwis Triumph over the Aussies New Zealand: 26 Australia: 12 Kiwi boys celebrating their historic win! O say I have been living the Tdream is something of an understatement. I have been involved in rugby league for more than 50 years and in that time I have had some highlights. Shaun Johnson lifts the trophy. Isaac Luke leads a Haka in honour of the fans after the game. The mighty Mangere East Hawks in the Fox Memorial, managing the Kiwis when we beat Australia 24-0 in 2005, and plenty with the Vodafone Warriors, two grand finals for a start. But Sunday’s 26-12 win over Aus- tralia was the best ever. Manu Vatuvei loves scoring tries. Shuan Johnson gets it over the line. Photos courtesy of www.photosport.co.nz Proud To Be A Kiwi Thanks For Your Support What can you say? Beating Aus- The week in Brisbane was fantastic tralia three times in a row has not and I must say I owe a big thank happened since 1953, so I am as you to those who sent emails in proud as I can be to be a Kiwis support of the Kiwis. I asked for supporter. your support, and I got it, with emails even coming in from Prime It was a fantastic game, built on Minister John Key, Minister of solid defence, and all credit to the Sport Jonathan Coleman, the Gov- NZRL and coach Stephen Kearney ernor-General, and Victoria Cross and his team. -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 23 February 2009 RE: Media Summary Tuesday 17 February to Monday 23 February 2009 Hewitt now heads Taranaki Rugby League Academy: A man who survived three days in the sea off the Kapiti Coast is warming to a new challenge. Waatea News reports Rob Hewitt has taken over the reins of the Taranaki Rugby League Academy. The former navy diver says sport is a way to get students thinking about their futures and to learn how to be successful on and off the field. However, he says, he was nervous at the start and "wanted out" two weeks ago. But now he's settled in. Hewitt will also continue his work as an ambassador for Water Safety New Zealand. Source: Radio New Zealand, 23 February 2009 Mannering keeps captain ambitions private: SIMON Mannering is refusing to buy into suggestions linking him to the future captaincy of the Warriors. Mannering's decision as revealed in last week's Sunday News to re-sign with the club despite the likelihood of making more money overseas, has prompted speculation that the loyal utility is a "captain in the making". His leadership potential is clear with Kiwis coach Stephen Kearney just last week heaping praise on him. Where did all the NZRL's money go?: Like any gambler, rugby league played the pokies, and at first, they got a few decent payouts. Encouraged, they hit the button one more time, and lost the lot. The unholy pairing of pubs and poker machines is the big reason rugby league found itself in such deep trouble that Sparc thumped in and demanded last week's damning Anderson Report, which called those sordid dealings a "sorry chapter" in the game's history, and declared: "This matter should now be regarded as a lesson learnt, and the sport should move on." Bennett tipped to return as Kangaroos coach after leaving Kiwis: WAYNE BENNETT'S odds of taking over as Kangaroos coach have been slashed after he stepped down yesterday from his role with New Zealand. -

By-Laws of Canterbury Rugby League Incorporated 2021 Season

By-Laws of Canterbury Rugby League Incorporated 2021 Season Contents Description Page number Section 1 By-Laws Object: 3 Section 2 By-Law Review: 3 Section 3 Definitions and Interpretations: 4 Section 4 Registration of Members 7 Section 5 Transfers/Clearances/Permits 7 Section 6 Grade Eligibility 10 Section 7 Competition Eligibility 11 Section 8 Grand Finals Series Eligibility 11 Section 9 Competition Rules 12 Section 10 Junior Competition Rules 14 Section 11 Grand Finals Rules 15 Section 12 Points & Tables 16 Section 13 Presidents Grade 17 Section 14 Out of Order player penalties 17 Section 15 Club Colours / Playing strip 18 Section 16 Changing rooms 18 Section 17 Team Cards 18 Section 18 Team Statistics 19 Section 19 ID Cards / ID Process 19 Section 20 Defaults 21 Section 21 Coaching/Team Officials Qualifications 22 Section 22 Representative 22 Section 23 Discipline 23 Section 24 Code of Behaviour 24 Section 25 Protests 24 Section 26 Player Sent off 24 Section 27 Appeals 25 Section 28 Finance 26 Section 29 Travelling Teams 26 Section 30 Sanctioned Events 26 Section 31 Health and Safety 27 Section 32 Banned Substances 27 Section 33 NZRL Concussion/Head Injury Policy 27 Appendix A – Club Colours 27 Appendix B – Automatic Player Suspensions 28 Appendix C – Fine Sanction Structure 30 Section 1 By-Laws Object: 1. Canterbury Rugby League Incorporated By-Laws are developed in line with Section 3 - Objects and Powers, of the Canterbury Rugby League Incorporated Constitution. 2. The intent of the By-Laws is to set in place policies, practices, processes and structure for the administration and delivery of the game of rugby league in a fair and unbiased manner. -

Mad Butcher Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch’s Mad Butcher Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 30 April 2015 Newsletter #70a To subscribe or unsubscribe email: [email protected] Kiwis and Junior Kiwis Training in Brisbane Photos courtesy of www.photosport.co.nz Support the Kiwis. Send an email of encouragement to [email protected] EXTER and I are living the make my debut as an interviewer. The word brotherhood gets used a Ddream, hanging out with the I don’t want to skite and do a lot lot, but it really means something Kiwis and Junior Kiwis in Bris- of name-dropping, so you will within the Kiwis. bane ahead of this weekend’s mas- just have to tune in to see who I sive round of international footy. collared. Three former players in David Solomona, Quentin Pongia and We owe a big vote of thanks to I don’t like to blow my own trum- Sam Panapa were all there, adding Kiwis coach Stephen Kearney and pet, because I am a pretty shy fel- their insights into what it is to pull NZRL boss Phil Holden for letting lah as you know, but I am expect- on the black and white vee. us be part of it. ing a call from TV producers the world over offering me my own Wednesday is the big team lunch, But despite having a ball, I’m dis- show as soon as this goes to air. Or with the Kiwis and Kangaroos all appointed there have not been a it could be that my debut might attending, so I’m looking forward few more emails in support of the coincide with my final appearance to catching up with a few of my boys, and indeed the Kiwi Ferns as an interviewer. -

A Word from Our Ceo Battle of the Bubbles

JUNE 2020 A WORD FROM OUR CEO BATTLE OF THE BUBBLES Kia Ora, The primary schools Battle of Excitement and anticipation is certainly building as the winter the the Bubbles challenge was a codes prepare to kick off the winter sports season. No doubt huge success! The first challenge many people in our community will need to ease back into was skipping which started at the physical activity after a number of weeks spent in lock-down beginning of lock down while the so please enjoy yourselves on your return and take care. schools were taking back children of essential workers, and parents were The ability to resume sport and recreation is a much-needed trying to find ways to keep their kids boost for our codes and clubs, and for our community active and amused at home. in general. I think it goes without saying that it’s been a challenging few months that has created a lot of uncertainty. Schools and parents logged skips each day with the goal of However, the last few months have also reinforced how winning the Battle of the Bubbles winning school! critical keeping active is to our well-being, and we need to At close off time Churton Primary School came out on top make sure this gets the recognition it deserves. with 27,425 skips logged, 2nd Place St John’s Hill Primary To our winter codes and clubs. A huge thank you for the School with 18,720 logged skips, and 3rd place Gonville quick actions and responses you all undertook to halt activity Primary School with 17,162 skips. -

Kiwi Ferns Junior Kiwis Kiwis

WANT A WEEKEND AWAY AND TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT FOR OUR 4 NATIONAL RUGBY LEAGUE TEAMS? The weekend of May 1st and 2nd will be a rare opportunity for New Zealand Rugby League fans to support all four national teams in Australia: the Kiwis, the Kiwi Ferns, the Junior Kiwis and the New Zealand Defence Force team. You wont want to miss it! Prior to the 2015 ANZAC Test Match will be a special pre-game entertainment extravaganza that will showcase the arena musical experience “The Spirit Of The ANZACS”. Some of Australia’s finest entertainers including Jack Thompson, Lisa McCune, Lee Kernaghan and Sheppard will honour 100 years of ANZAC pride with a musical journey through ANZAC history. • The opening game will be the NZ Defence force vs Australian Combined Armed Services • The curtain raiser will see the Kiwi Ferns take on the Australian Jillaroos. • Tickets from just $30 AUD. Use password Kiwi2015 to access discounted prices. Here. • In addition the following day, just down the road on the Gold Coast there will be a massive triple header: Junior Kiwis v Junior Aussies, Fiji v PNG and Tonga v Samoa at Cbus Stadium. Tickets for this Triple Header from just $10. Click on the images to learn more... This will be a great lunch with both teams attending! Confident Kearney Senses Elusive ANZAC Test Triumph By David Long - Article from Sunday Star Times E HAS steered the Kiwis to a world cup win and two Four Nations titles, but an Anzac test victory re- Hmains an elusive goal for Stephen Kearney. -

2016 NSWRL Referees Association Annual Report

2016 NEW SOUTH WALES RUGBY LEAGUE REFEREES’ AssOCIATION 109 TH ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENT 2 NEW SOUTH Wales RUGBY LEAGUE REFEREES’ ASSOCIation 109 TH ANNUAL REPORT & FINANCIAL STATEMENT 3 CONTENTS 4 Notice to all members 28 Michael Stone Medal Recipients 5 Board of Directors 2016 28 Col Pearce Medal Recipients 6 Board of Directors and Sub Committees 2016 28 Kevin Jeffes Trophy Recipients 7 Patron’s Report 28 Jack O’Sullivan Trophy Recipients 8 Chairman’s Report 29 Life Membership Honour Roll and Attendance 10 Executive Officer’s Report 29 Graded Referees Season 2016 and Attendance 13 Vales 30 Life Members in Memoriam 14 Director of Finance Report 30 Honorary Associate Members for Life 16 Financial Statements 31 Financial Non-Active Members 2016 and Attendance 18 Director of Referee Development and Affiliate Liaison Report 32 Affiliated Associations Delegates 2016 and Attendance 19 Summary of Member Services Provided 32 Inter-District Representative Squad 2016 20 NSW State Cup Squad Coach’s Report 33 Board of Directors Honour Roll 22 NRL Elite Performance Manager’s Report 33 Past Presidents, Secretaries and Treasurers 24 Inter-District Development Squad Coach’s Report 34 Representative Appointments 2016 25 The NSWRLRA 300 Club 37 Positions held by members with the NSWRL & NRL 26 George and Amy Hansen Memorial Trophy Recipients 37 Board of Directors Meeting Attendance Record 26 Frank Walsh Memorial Trophy Recipients 38 Minutes of the 108th AGM 27 Dennis Braybrook Memorial Trophy Recipients 40 Membership Record 1908-2016 27 Bill Harrigan Trophy Recipients 42 Results of Elections 27 Eric Cox Medal Recipients 42 Credits 27 Michael Ryan Award Recipients 27 Les Matthews Award Recipients Adam Devcich refereeing in the Intrust Super Premiership NSW Front Cover Damien Briscoe officiating in the Intrust Super Premiership NSW. -

New Zealand Rugby League Marketing and Communications Manager

February 2019 POSITION DESCRIPTION New Zealand Rugby League Marketing and Communications Manager February 2019 JOB TITLE: Marketing and Communications Manager ORGANISATION: New Zealand Rugby League LOCATION: Penrose, Auckland, New Zealand REPORTING TO: GM Commercial and Communications ABOUT NEW ZEALAND RUGBY LEAGUE: Rugby league has played a significant part in New Zealand sport for over 100 years. Formed in 1910, New Zealand Rugby League (NZRL) is the governing body for the sport of rugby league in New Zealand. The NZRL catchment is divided into seven zones that service the grassroots needs of the game. These zones compete in the National Championship, as well as women’s, youth and schools competitions. The NZRL manages the Kiwis and Kiwi Ferns who are both currently ranked number two in the world. NZRL is not just about success on the field - it is also charged with caring for a community off-field, promoting the values of integrity, respect, leadership, courage and passion. The “more than just a game” philosophy has seen NZRL establish innovative social development programmes using rugby league to help communities improve their lives off the field. NZRL VISION: • Building a stronger family and community game NZRL MISSION: • To lead and inspire people through their Rugby League experience KEY FOCUS • Increase participation • Building capability and support • Funding to enable performance and growth • Success on the international stage OUR 5 YEAR GOALS • Stronger Rugby League Communities • Better Rugby League experiences • Financially sustainable game • Rugby League World Cup winners POSITION PURPOSE: The Marketing & Communications Manager has responsibility to deliver: • the Brand strategy; • the Communications strategy including Digital; and • Implementation of all marketing and communications plans across a range of digital and social channels. -

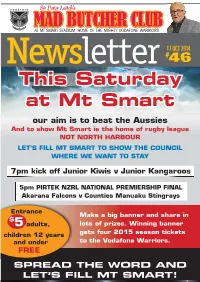

Spread the Word and Let's Fill Mt Smart!

17 OCT 2014 #46 This Saturday at Mt Smart our aim is to beat the Aussies And to show Mt Smart is the home of rugby league NOT NORTH HARBOUR LET’S FILL MT SMART TO SHOW THE COUNCIL WHERE WE WANT TO STAY 7pm kick off Junior Kiwis v Junior Kangaroos 5pm PIRTEK NZRL NATIONAL PREMIERSHIP FINAL Akarana Falcons v Counties Manuaku Stingrays Entrance Make a big banner and share in $ 5 adults, lots of prizes. Winning banner children 12 years gets four 2015 season tickets and under to the Vodafone Warriors. FREE SPREAD THE WORD AND LET’S FILL MT SMART! If ever there was a great chance for rugby league fans to show Auckland City we love Mt Smart it comes this Saturday when the Junior Kiwis play Australia at 7pm. You can talk the talk but at some stage you have to walk the walk, and that stage is Saturday. And it will only cost league fans: $5 – with Under 12s free As you know there are all sorts of plans to move the Vodafone Warriors, and they all come down to dollars. You can take fl ower boxes for a few million in Queen St, and you can take millions for offi ces for people who can’t process a building application without dynamite strapped to their backsides, and you can take millions of dollars for any other hare-brained scheme the council comes up with. But few chances to show the council how much us poor league fans love Mt Smart come up. There has been talk of a march down Queen St but they are a dime a dozen, and this Saturday gives us the chance to do something totally different. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 11th May 2016 Newsletter #121 New Zealand vs Australia Shaun Johnson tackled by Greg Inglis Kiwis dejected after their loss. Kevin Proctor tackled by Corey and Johnathan Thurston. Parker. The Kiwi Ferns after their win. Kiwi Fern Atawhai Tupaea scores a Kiwi Ferns player Kahurangi Peters try. fends Vanessa Foliaki. Brandon Smith of the Junior Kiwis is Greg Lelesiuao of the Junior Kiwis is Ma’afoaeata Hingano of the Junior tackled. tackled. Kiwis scores a try. Photos courtesy of www.photosport.nz The Road to Redemption By David Kemeys O POINT trying to dodge it, the only thing anyone has been talking about is the six in the donger for Nthe night out and prescription pills incident. But some of the dumbest stuff I have ever seen has been published around it, and social media makes that easy. But I did see two pieces that demanded attention – neither from mainstream journalists. One was on Stuff Nation by someone called Jeremy Brown. He talked at length about stuffing up big style, but I will spare Jeremy the embarrassment of repeating it all, suffice to say he was as pissed as a rat –as most of us have been - and made an arse of himself – as most of us have done. Like me, Jeremy put the pills and energy drink decision in the “poor” category. But then he suggested something not many in the media have advocated. It was: Accept there have been consequences, the players have been punished, and move on.