Housing in Lakes and Bay of Plenty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centre Handbook

2020-2021 SEASON Centre Handbook www.bowlsbop.co.nz Phone: 027 210 8338 For all your highest quality Bowls, Clothing, Bags and Accessories, contact: Pat Dean Bay of Plenty 07 544 8118 [email protected] Chevalier Bo 25 Dignan St, Point Chevalier, Auckland 09 846 6728 Bo ' www.bowIsonline.co.nz :See l,u n ,i;e l it e." <1>.n ::z for- ,i;,p,- full r-a1J:ge ,i;,f bowl,i; p r-o ,,h " u BOWLS BAY OF PLENTY (INC) CONTENTS President’s Message ........................................................................................ 3 Board Officers ................................................................................................... 7 Board Members ................................................................................................ 9 Umpires Association .................................................................................... 11 Divisional Officers ......................................................................................... 13 Centre Selectors & Managers .................................................................. 14 Youth Development ...................................................................................... 14 The Website ..................................................................................................... 15 BOP Greenkeepers Association .............................................................. 17 NZ Blind Lawn Bowls Association ........................................................ 18 NZ Disabled Lawn Bowls Assn ............................................................... -

Bay of Plenty Secondary Schools 2020 Handbook

Bay of Plenty Secondary Schools 2020 Handbook SECONDARY SCHOOL CONTACTS CHAIRPERSON Carleen James School: 07 349 5940 Email: [email protected] DEPUTY CHAIRPERSON Tuahu Waretini-Thomas Phone: 07 575 3096 Email: [email protected] DRAW STEWARD BOP Rugby Union SKED Competition Platform Contact: Pat Rae [email protected] AQUINAS COLLEGE Ange McManaway Phone: 07 543 2400 Email: [email protected] BETHLEHEM COLLEGE Andy Bartrum Phone: 07 576 6769 Email: [email protected] EDGECUMBE COLLEGE Lisa Robinson Phone: 07 304 8211 Email: [email protected] JOHN PAUL COLLEGE Tim Hounsell Phone: 07 347 8795 Email: [email protected] KATIKATI COLLEGE Angus Donald 33 Beach Rd, Katikati Phone: 07 549 0434 Email: [email protected] MOUNT MAUNGANUI COLLEGE Tuahu Waretini-Thomas Phone: 07 575 3096 Email: [email protected] MURUPARA AREA SCHOOL Tanetiki Takuira (Sports Co-ordinator) 84 Pine Dr, Murupara Phone: 07 366 5601 Email: [email protected] OPOTIKI COLLEGE Sophie Takamore (Sports Co-ordinator) St Johns St, Opotiki Phone: 07 315 7022 Email: [email protected] OTUMOETAI COLLEGE Paul Braddock 105 Windsor Rd, Bellevue, Tauranga Phone: 07 576 2316 Email: [email protected] PAPAMOA COLLEGE Nick Leask 151 Doncaster Dr, Papamoa Phone 07-542 0676 Email: [email protected] REPOROA COLLEGE Kirsten Fairley Massey Rd, Reporoa Phone: 07 333 8117 ext 2 Email: [email protected] ROTORUA BOYS HIGH SCHOOL Deon Muir Co Director Ngarimu Simpkins Co Director -

A Deprivation and Demographic Profile of the Lakes DHB

A deprivation and demographic profile of the Lakes DHB Lakes DHB, showing overall IMD deprivation with the most deprived areas shaded darkest Rachael Yong, Michael Browne, Dr Jinfeng Zhao, Dr Arier Chi Lun Lee, Dr Nichola Shackleton, Dr Sue Crengle, Dr Daniel Exeter 17/10/2017 Statistics New Zealand Disclaimer The results in this report are not official statistics, they have been created for research purposes from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), managed by Statistics New Zealand. The opinions, findings, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) not Statistics NZ or the University of Auckland. Access to the anonymised data used in this study was provided by Statistics NZ in accordance with security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. Only people authorised by the Statistics Act 1975 are allowed to see data about a particular person, household, business, or organisation and the results in this paper have been confidentialised to protect these groups from identification. Careful consideration has been given to the privacy, security, and confidentiality issues associated with using administrative and survey data in the IDI. Further detail can be found in the Privacy impact assessment for the Integrated Data Infrastructure available from www.stats.govt.nz. The results are based in part on tax data supplied by Inland Revenue to Statistics NZ under the Tax Administration Act 1994. This tax data must be used only for statistical purposes, and no individual information may be published or disclosed in any other form, or provided to Inland Revenue for administrative or regulatory purposes. -

Todd Muller Mp for Bay of Plenty

TODD MULLER MP FOR BAY OF PLENTY Community Newsletter | Autumn 2021 I often wonder as I sit in the dark of our Mount It is always risky to call out individuals but I have Maunganui dawn service listening to the waves four names I want to acknowledge: fold gently upon each other whether I would Bryce McFall and Amanda Lowry whose work have thrown myself into the water like those with our disabled athletes to help them be the landing in Gallipoli or Normandy. best they can be is just stunning. Whether I would have driven on into the desert Andrew Hitchfieldand Jim Pearson, from valleys of the Middle East and North Africa or Papamoa Surf Lifesaving Club who have worked slashed through impenetrable jungles of Asia. In for years and years to get our new surf club my bravest moments I tell myself I would have built. and so would my friends, but if I am honest I find their bravery and courage daunting beyond These four will immediately say they are part of measure. I am particularly moved by the humility a much wider team, which of course is true, but of our service men and women. someone has to lead, someone has to serve, and in these four we have great community To those who think that the greatest (WW2) examples. generation can’t be replicated, I can give you confidence that our current service women and We live in a remarkable community at a men are exemplary. In 2017 I was very privileged profoundly challenging time. -

M601 LRCA December Newsletter 3.Indd

NEWSLETTER LAKE ROTOITI SUMMER COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION INC. 2012/13 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT DECEMBER 2012 AGM: The Annual General Meeting of our Association will be SEWERAGE: I refer you to Phill Thomass’s article in respect of held on Wednesday, 2nd January 2013 at the Pikiao Rugby League the current RDC thinking on proposed installation of sewerage Clubrooms, Takinga Street, Mourea at 10 am. It is important to us reticulation to Eastern Rotoiti and Rotoma. Our Association was that all residents attend this meeting and put forward their views. party to the Environment Court Hearing, along with Tamatea Street Light refreshments will be served following the meeting. We look Ratepayers Association and we are keenly watching developments. forward to seeing you there! It is heartening to know that pricing has fi nally been acknowledged as a key factor for Eastern Rotoiti residents. The initial proposed RATES: The RDC 2012-2022 Long Term plan indicates a move costings for our residents affected by this schme have always been from the present rating system with differentials (rural residential of great concern to us. properties are currently 85%) to a system with no differentials. Jim Stanton of our Committee and Brentleigh Bond, Chair of the JETTIES: In a recent draft of its ‘Public Lake Structures Policy’, Lakes Community Board, have consistently advocated for rural RDC has signalled its desire to reduce the total number of private communities and it is important for us to realise that should the lake structures (jetties, boatsheds, moorings etc.) in some of the differential be removed in one jump this could be expected to District’s lakes. -

May 2015 Web File

NGONGOTAHA NEWS The Sunny side of the Mountain - FLUORIDE FREE NGONGOTAHA Editor Ann Henderson - email: [email protected] Mob: 027 2379 204 website: www.ngongotahanews.co.nz Next deadline JUNE 12TH 2015 11am May 2015 issue “CARING IS SHARING IN NGONGOTAHA” Maori Wardens have been active on the ground in Ngongotaha for the past 10 years conducting mobile services however, since late January of this year and due to community concerns Maori Wardens are now domiciled in Ngongotaha at the Community Policing Centre. If you have not met them already, pop into the centre and say Hi to “Yvonne & Ben”. I would personally like to acknowledge and thank all of the people that I have been involved with in making “Project Suburb” a success. To the people of Ngongotaha, thank you for taking care of Yvonne & Ben and welcoming them into your community followed by your support to them. Role of a Maori Warden • Community Support – focused and united services out in the Communities. • To Promote Cultural Integrity and Understanding in the community. • To assist and support all People. • To encourage youth to take advantage of educational and vocational opportunities to enhance their future Relationships • The Maori Wardens are not Police Personnel. Maori Wardens have a working relationship with the New Zealand Police. • We have direct contact with Police 24/7 for our own safety when out during the day or late nights patrolling. • New Zealand Police provide training and resources to assist wardens to work in the fields of Prevention – Response & Protect. -

Bowls Bay of Plenty Incorporated

BOWLS BAY OF PLENTY INCORPORATED Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of Bowls Bay of Plenty Incorporated held at the Rotorua Bowling Club at 10.00 a.m. on Sunday 9th August 2020. Welcome The Centre President Mr Ross Harvey opened the meeting and welcomed the Delegates, Board Members and observers. Obituary Ross Harvey asked that all present to stand for a moments silence in remembrance for those Bowlers and family members who had passed on during the last year. Special mention of Brendon Neutze Speaking Rights. Moved: That speaking rights be accorded to Centre Board Members, the Centre Manager and CEO of Bowls NZ (Mark Cameron). Moved: Kawerau Seconded: Taupo CARRIED Roll Call Board Members Ross Harvey (Chair, President), John Foreman, Diane Smith, Graham Skellern, Derek Kendall, Liz Witton. Geoff Tuckey (Acting Centre Manager) Club Delegates Arawa Tom MacKenzie, Ian Thompson, Alan McCauley Bowls Mt Maunganui Kevin Maxfield, Noel Topp, Keith Arthur Bowls Tauranga South Judith Payne, Karin Clarke Bowls Matua Chris Neilson, Jim Wilson Edgecumbe In recess Katikati Not Present Kawerau Marcus Merrick, Brian Dixon Ngongotaha Lil McGregor, Mere Eden Ohope Margaret O’Regan, Jocelyn Jones Omanu In Recess Omokoroa Ross Harvey, Bill Murphy, Gary Russek Opotiki Apologies Papamoa Bob Dunning, Lynne Bodger Reporoa Ross Henderson, Peter Kelly Rotorua Robert Clarke, Conan O’Brien Rotorua East Harold Hunt, Rob Bell Taupo David Jones, Darrell Purdie Tauranga Paul Hunt, Steve Hughes, Marilyn Constantine Te Puke Brian Bennett, Bill Reid, Merv Gibbons Turangi Not Present Whakatane John Foreman, Don Warren, Kathy DEmpster-Rivett Apologies Moved That the apologies of Opotiki Club, John Chelley, Peter Joyce, Rod Warrender, and Ken Boyle be sustained Moved: Matua Seconded: Tauranga CARRIED Minutes of the 2019 Bowls BOP AGM. -

Bright Idea Lights Museum

Page 5Rotorua Page 9Passion DO YOU HAVE AN EMPTY QUALITY FURNISHED HOME, tourism on the for election AND YOU WANT TO MAKE SOME SERIOUS DOLLARS? up CALL NORMAN AT 2LAKES HOLIDAY RENTALS FOR A FREE APPRAISAL FOR SHORT TERM RENTALS NGA HUINGA KORERO O ROTORUA AU-7334006AB Using [email protected] Rotorua Review Ph 07 3628056, 027 4950189 Wednesday, September 21, 2016 Tripping the light fantastic at Rotorua Museum. BENN BATHGATE/FAIRFAX NZ Bright idea lights museum BENN BATHGATE marked with the switching on of munity in a way that we haven’t Rotorua Museum Centennial buildings in New Zealand, it’s the Museum’s new LED light been able to in the past,’’ he said. Trust chair Lyall Thurston said iconic and this new lighting is an The ‘light bulb moment’ - the array by Rotorua MP Todd ‘‘By illuminating the building, the lighting was ‘‘the icing on the initiative we can all be proud of,’’ idea to light up Rotorua’s iconic McClay. we’re able to celebrate the Bath cake’’ of the Trust’s upgrade he said. Museum with LED lighting - came Museum director Stewart House building’s iconic status and work, which began in 2006. ‘‘It’s destined to blow Rotorua’s in 2008. Brown said technical advances stand proudly alongside other ‘‘The floodlighting alone will socks off.’’ Unfortunately, it also came since 2008 meant they had been landmarks in support of local, be a tourist must see. Full marks Before switching the lights on with a number of technical able to install radio controlled national and international causes to Museum director Stewart McClay said it was ‘‘magnificent problems and a bill of $1.9 million. -

Rotorua District Alcohol Ban Bylaw 2018

RDC-871644 ROTORUA DISTRICT ALCOHOL BAN BYLAW 2018 1 Overview This Bylaw prohibits the consumption and restricts the possession and transportation of alcohol in specific public places within the Rotorua District (called Alcohol Ban Areas). Alcohol Ban Areas may be permanent or temporary, and in either case may apply to certain hours or days. Within Alcohol Ban Areas, the consumption of alcohol is not permitted in specified public places such as parks, footpaths, lakesides, beaches or roads, but is permitted on private land such as licensed premises or private residences. This Bylaw does not apply to matters relating to licensed premises or the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act 2012. A breach of this Bylaw is an infringement which, on conviction, can result in a fine of up to $20,000. 2 Part 1: Preliminary Provisions Pursuant to sections 145 and 147 of the Local Government Act 2002 (the Act), Rotorua District Council makes the following Bylaw: 1. Short Title and Commencement This Bylaw is the Rotorua District Alcohol Ban Bylaw 2018, and comes into force on 22 November 2018. 2. Purpose The purpose of this Bylaw is to reduce alcohol-related harm, damage, disorder and crime and to improve community safety by putting alcohol restrictions in some public places. 3. Interpretation (1) In this Bylaw, unless the context requires otherwise: Act means the Local Government Act 2002. Council means the Rotorua District Council or any person delegated to act on its behalf. Christmas to New Year holiday period means Christmas Eve (the day before Christmas Day) to the day after New Year’s Day as determined by the Holidays Act 2003. -

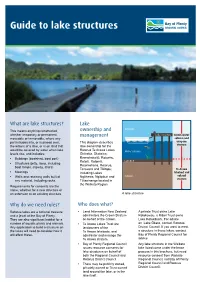

Guide to Lake Structures

Guide to lake structures What are lake structures? Lake Airspace This means anything constructed, ownership and whether temporary or permanent, management Lake structure Crown water moveable or immovable, where any column and part intrudes into, or is placed over, This diagram describes airspace stratum the waters of a lake, or is on land that lake ownership for the would be covered by water when lake Rotorua Te Arawa Lakes Water column levels rise, and includes: Ōkāreka, Ōkataina, ▪ Buildings (boatshed, boat port) Rerewhakaitū, Rotoehu, Rotoiti, Rotomā, Lakebed ▪ Structures (jetty, ramp, including Rotomahana, Rotorua, boat ramps, slipway, stairs) Tarawera and Tikitapu; Te Arawa ▪ Moorings including Lakes lakebed and subsoil ▪ Walls and retaining walls built of Ngāhewa, Ngāpōuri and Subsoil stratum any material, including rocks. Tūtaeinanga located in the Waikato Region. Requirements for consents are the same, whether for a new structure or an extension to an existing structure. A lake structure Why do we need rules? Who does what? Rotorua lakes are a national treasure ▪ Land Information New Zealand A private Trust owns Lake and a jewel of the Bay of Plenty. administers the Crown Stratum Rotokawau, a Māori Trust owns They are also significant habitat for a on behalf of the Crown. Lake Rotokākahi. For advice number of aquatic plants and animals. ▪ Te Arawa Lakes Trust are on Lake Ōkaro, contact Rotorua Any application to build a structure on landowners of the District Council. If you want to erect the lakes will need to consider how it Te Arawa lakebeds, and a structure in these lakes, contact will affect these. administer and manage the Bay of Plenty Regional Council for Te Arawa stratum. -

Evolving Community Response to Tourism and Change in Rotorua

Evolving Community Response To Tourism and Change in Rotorua Chrys Horn Researcher, Human Sciences Division, Lincoln University. [email protected] David G Simmons Professor of Tourism, Human Sciences Division, Lincoln University. [email protected] John R Fairweather Principal Research Officer in the Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, Lincoln University. [email protected] February 2000 ISSN 1174-670X Tourism Research and Education Centre (TREC) Report No. 14 Lincoln University Contents LIST OF TABLES vi LIST OF FIGURES viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x SUMMARY xii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction....................................................................................1 1.2 Report Structure .............................................................................3 CHAPTER 2 METHODS..............................................................................................5 2.1 Qualitative Methods.......................................................................5 2.2 Quantitative Survey........................................................................6 2.3 Weighting.......................................................................................9 2.4 Presentation....................................................................................9 2.5 Limitations of Research ...............................................................10 CHAPTER 3 THE ROTORUA CONTEXT: HISTORY AND SOCIAL PATTERNS..........................................................................................11 -

Ngongotaha News February 2020 Issue

NGONGOTAHA NEWS The Sunny side of the Mountain - FLUORIDE FREE NGONGOTAHA Editor Ann Henderson Mob: 027 2379 204 Email: [email protected] website: www.ngongotahanews.co.nz NEXT DEADLINE: MARCH 2020 FEBRUARY 2020 ISSUE RUGBY FAMILY FUN DAY NGONGOTAHA SENIORS VS WAIHOU SATURDAY 7TH MARCH 2.45 KICKOFF COME JOIN US - @ THE MAMAKU DOMAIN MAMAKU STREET MAMAKU HANGI AVAILABLE 1 TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS Kelly Lelieveld B Bus, CA If you think you could be getting more for your accounting dollar, for example a service that: [email protected] 021 804 544 ~ Has someone local that you can talk to ~ Understands business moneymetrics.co.nz ~ Can save you valuable time ~ Doesn’t cost the earth ~ Has the highest professional standards ~ Can assess if Xero is right for you Then contact Kelly Lelieveld at Money Metrics. Kelly is a Chartered Accountant with extensive experience over many industries. Kelly is passionate about business & would love the opportunity to talk with you so, for a free no-obligation meeting, contact Kelly now! SOME DO'S AND DON'TS On Wedding Attendance: A man walks into a bar one night, he goes up the barman and • Livestock is usually a poor choice for a wedding gift asks for a beer. "Certainly sir, that'll be 1cent" • If you are so honoured to be the groom, it is best to Are you sure exclaimed the guy, "Yes" says the barman. refrain from bringing a date So the guy glances over the menu and asks if he could • When dancing, never remove undergarments, no matter have a nice juicy T bone steak with fries, peas and a salad.