International Intellectual Property Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patent Rights and Local Working Under the WTO TRIPS Agreement: an Analysis of the U.S.- Brazil Patent Dispute

Patent Rights and Local Working Under the WTO TRIPS Agreement: An Analysis of the U.S.- Brazil Patent Dispute Paul Champt and Amir Attarant I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................365 II. HISTORY OF PATENTS AND LOCAL WORKING REQUIREMENTS ....................................................370 fiI. A NEGOTIATING HISTORY OF TiE TRIPS AGREEMENT AND LOCAL WORKING ..........................373 IV. LOCAL WORKING AND THE BRAZIL DISPUrE ...............................................................................380 A . Background .........................................................................................................................380 B . Article 31 .............................................................................................................................383 C. Article27(1) ........................................................................................................................386 V . CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................390 I. INTRODUCTION Before settling a recent WTO dispute with Brazil, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) came perilously close to creating a full-scale public relations disaster for the U.S. government and perhaps for the entire WTO system.' The U.S. challenge concerned a provision of Brazilian patent law 2 that Brazil says it can use to issue compulsory licenses3 -

The Public Interest and the Construction of Exceptions to Patentee's Rights

The Public Interest and the Construction of Exceptions to Patentee's Rights - A comparative Study of UK and German law by Marc Dominic Mimler A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen Mary, University of London 2015 Statement of Originality I, Marc Dominic Mimler, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Marc Dominic Mimler Date: 28 May 2015 2 Abstract The thesis analyses the concept of public interest with regards to exceptions to patent rights. It is submitted that patent rights are generally provided for a utilitarian purpose which is to enable technological advance. This goal is meant to be achieved by providing exclusive rights over the patented invention. -

The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices

CRIDES Working Paper Series no. 2/2020 The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices by Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard February 2020 Cite as: Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard, The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices, CRIDES Working Paper Series no.2/2020 The CRIDES, Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire Droit Entreprise et Société, aims at investigating, on the one hand, the role of law in the enterprise and, on the other hand, the function of the enterprise within society. The centre, based at the Faculty of Law – UCLouvain, is formed by four research groups: the research group in economic law, the research group in intellectual property law, the research group in social law (Atelier SociAL), and the research group in tax law. www.uclouvain.be/fr/instituts-recherche/juri/crides This paper © Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard 2020 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ THE RISKS OF PATENT LITIGATION WITHIN THE EU ENFORCEMENT FRAMEWORK HOW TO ADDRESS ABUSIVE PRACTICES Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices By Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard* Keywords: Patent litigation, Flexibility and Injunctive Relief, Proportionality, Abuse of Rights, Patent Assertion Entities, Patent Trolls, Article 3(2) Enforcement Directive, Directive (EU) 2004/48 Abstract The debate over the degree of flexibility at the disposal of national courts in Europe to grant, deny, or tailor, injunctive relief in patent litigation seems to be a never-ending story. -

Global Access to Medicine: the Influence of Competing Patent Perspectives

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 35, Issue 1 2016 Article 7 Global Access to Medicine: The Influence of Competing Patent Perspectives Cynthia M. Ho∗ ∗Loyola University Chicago School of Law Copyright c 2016 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj ARTICLES GLOBAL ACCESS TO MEDICINE: THE INFLUENCE OF COMPETING PATENT PERSPECTIVES Cynthia M. Ho* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 3 I. BACKGROUND ............................................................................ 8 A. Intellectual Property Rights .............................................. 8 1. Patents .......................................................................... 9 2. Trademarks ................................................................ 11 B. Drugs in the Marketplace................................................ 13 1. Drug Safety ................................................................. 13 2. Terminology ............................................................... 15 a. What is a Generic Drug? ...................................... 15 b. Generic vs. Counterfeit Drugs ............................. 16 II. A NEW FRAMEWORK .............................................................. 18 A. Social Science Foundation .............................................. 19 1. Schemas ...................................................................... 19 2. Confirmation Bias ..................................................... -

Would Utility Models Improve American Innovation? Evidence from Brazil, Germany, and the United States

BOSCHERT FINAL 2.8.2014 IP MACRO (DO NOT DELETE) 8/19/2014 3:31 PM WOULD UTILITY MODELS IMPROVE AMERICAN INNOVATION? EVIDENCE FROM BRAZIL, GERMANY, AND THE UNITED STATES TYLER J. BOSCHERT* INTRODUCTION: THE UTILITY MODEL CONCEPT AND THE EFFECTS OF PATENT LAW ON INNOVATION .............................................. 134 I. THE ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK: THE GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX AS AN INDICATOR OF INNOVATIVE QUALITY ................. 136 II. ANALYSIS:THREE CASE STUDIES IN UTILITY MODEL REGIMES ...... 138 A. The "Strong" Utility Model Regime: Brazil.......................... 140 B. The "Weak" Utility Model Regime: Germany ...................... 143 C. The No-Utility-Model Regime: The United States ............... 145 III. CONCLUSION: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN PATENT LAW ........................................................... 148 APPENDIX A: ......................................................................................... 152 GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX INPUT VARIABLES, WITH RELATIVE WEIGHTS IN GII.......................................................................... 152 APPENDIX B: ......................................................................................... 157 GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX OUTPUT VARIABLES, WITH RELATIVE WEIGHTS IN GII.......................................................................... 157 APPENDIX C: ......................................................................................... 159 GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX DATA FOR BRAZIL ................................. 159 APPENDIX -

World Intellectual Property Organization Geneva

E WIPO SCIT/ATR/PI/1999/DE WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION GENEVA STANDING COMMITTEE ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES ANNUAL TECHNICAL REPORT 1999 ON PATENT INFORMATION ACTIVITIES* submitted by GERMANY An annual series of reports on the patent information activities of members of the Standing Committee on Information Technologies * – The term “patent” covers utility models and SPCs. – Information related to design patent activities reported by industrial property offices issuing design patents is included in the series of documents SCIT/ATR/ID. I. Evolution of patent activities In 1999, 94 067 patent applications were registered at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office. 58 363 of these were filed directly with the GPTO and 35 704 as inter- national applications under the Patent Co-operation Treaty (PCT). 2 920 international applications entered the national phase at the GPTO. This marks the continuation of the clearly positive development of the number of applications, observable in the past few years (see the GPTO's "Annual Report 1999"). This applies also to applications from Germany. The fact that 51 105 domestic appli- cations were filed in 1999, i.e. 3 472 more applications than in the previous year, has proved that the German patent system is highly valued by the national industry. After all, patent applicants in Germany filed 200 applications per working day in 1999, and altogether 62 applications per 100 000 inhabitants. II. Matters concerning the generation, reproduction, distribution and use of primary and secondary sources of patent informa- tion II.1. Publishing, printing, copying The following numbers of documents were published in 1999: 39 665 Offenlegungsschriften (Unexamined patent applications, A1) 15 580 Patentschriften (Patent specifications, C1, C2, C3, C4) 19 571 Gebrauchsmuster (Utility models, U1) 27 427 Translations of European patent specifications (T2, T3, T4). -

Program Taught by Leading Judges and Practitioners from Both Countries

The Federal Circuit Bar Association, with support from the German Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property, is pleased to continue its Global Fellows Series. An extraordinary success, this new series promotes a higher level of international IP practice among the next generation of leaders in the global legal community. The intent of the Global Fellows Series is to bring together a small group of future leaders in the global legal community for an intensive learning program taught by leading judges and practitioners from both countries. In an interactive small-group learning environment, these emerging leaders will together focus on both policy issues and practical lessons on the operation of the patent systems in Europe and the US, enhancing their ability to provide effective legal service to clients. The Global Fellows also develop professional relationships crossing international boundaries and legal cultures that we hope will endure throughout their legal careers. The Fellows will convene for two sessions, tentatively scheduled for first in Washington, DC, from October 4-7, 2016, and then in Munich from March 7-10, 2017. The number of available spaces is limited to 26 with balanced participation from major jurisdictions across the globe. Those who are interested in participating should submit an application by August 29, 2016. An application form can be filled out online here. If you or your organization has an interest in participating, or wish to obtain more information on the Global Fellows Series, please contact Mr. James Brookshire, Executive Director, FCBA, [email protected]. Program The program has two sessions, one in Washington, DC and the other in Munich, Germany. -

Patent Infringement by Transit of Goods Through Germany by Clemens Rübel

4 BARDEHLE P AGENBERG D OST ALTENBURG G EISSLER Patent infringement by transit of goods through Germany By Clemens Rübel The German patent law enumerates the “acts of use” that are exclusive to the patent holder, specifying the manufacturing, offering, distributing and the use or import or owning for these purposes. This enumeration of the acts of use of a patented invention is being expanded by one more act exclusive to the patent holder which is said to have been created by interpretation of the term “distributing” in the case law of a patent infringement court: transit. This “new” act of use is of considerable practical importance, in particular in Germany, which by its central geographical situation in Europe and in the European Union has become an important country of transit. The high practical relevance of a law granting to the patent owner the right to interdict transit is resulting from the ever growing claims to border seizure of IPR infringing goods by the custom authorities in Germany. Many of the goods seized at the German borders or at harbors and airports on the basis of the European Regulation (EC) 1383/2003 are in transit through Germany. If transit was not treated as potential patent infringement, the sharp sword of border seizure in these rather frequent cases would be ineffective since if evidence was provided that the goods were indeed on “mere” transit, the goods would have to be released. Patent owners therefore welcome the tendency triggered by a decision of the Hamburg District Court of April 2, 2004 which contrary to the case law to-date sees “mere” transit as an act of use reserved to the patent holder regards it as a sub-category of “distributing”, not least in order to prevent cases of misuse when goods declared for transit ultimately end up in Germany. -

Patent Protection for Plants: Legal Options for Developing Countries

Research Paper 55 October 2014 PATENT PROTECTION FOR PLANTS: LEGAL OPTIONS FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Carlos M. Correa RESEARCH PAPERS 55 PATENT PROTECTION FOR PLANTS: LEGAL OPTIONS FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Carlos M. Correa SOUTH CENTRE OCTOBER 2014 THE SOUTH CENTRE In August 1995 the South Centre was established as a permanent inter- governmental organization of developing countries. In pursuing its objectives of promoting South solidarity, South-South cooperation, and coordinated participation by developing countries in international forums, the South Centre has full intellectual independence. It prepares, publishes and distributes information, strategic analyses and recommendations on international economic, social and political matters of concern to the South. The South Centre enjoys support and cooperation from the governments of the countries of the South and is in regular working contact with the Non-Aligned Movement and the Group of 77 and China. The Centre’s studies and position papers are prepared by drawing on the technical and intellectual capacities existing within South governments and institutions and among individuals of the South. Through working group sessions and wide consultations, which involve experts from different parts of the South, and sometimes from the North, common problems of the South are studied and experience and knowledge are shared. NOTE Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce the contents of this Research Paper for their own use, but are requested to grant due acknowledgement to the South Centre and to send a copy of the publication in which such quote or reproduction appears to the South Centre. The views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the South Centre or its Member States. -

Amendments to the German Patent and Utility Model Law

Amendments to the German Patent and Utility Model Law I. German Patent Law In order to implement the EU directive on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions (“biopatent directive”, 98/44/EG of July 6, 1998), the German patent and utility model law was amended in January 2005. The new law came into effect as of February 28, 2005. (Please note that the following translation is no official translation but has been prepared in our office) In particular, the German Patent Law was amended as follows: 1. A new subsection 2 is introduced into § 1 German Patent Law (PatG) which states that patents ... are also granted for inventions which concern a product consisting of or containing biological material, or a process by means of which bio- logical material is produced, processed or used. Thus, the German Patent Law now explicitly acknowledges the patentability of inventions relating to biological material; this issue has recently been the subject matter of extensive political and ethic debate in Europe and Germany. 2. Of special importance is newly introduced § 1a which reads as follows: § 1a (1) The human body, at the various stages of its formation and development, including the germ cells and the simple discovery of one of its elements, including the sequence or partial sequence of a gene, cannot 2 constitute patentable inventions. (2) An element isolated from the human body or otherwise produced by means of a technical process, including the sequence or partial sequence of a gene, may constitute a patentable invention, even if the structure of that element is identical to that of a natural element. -

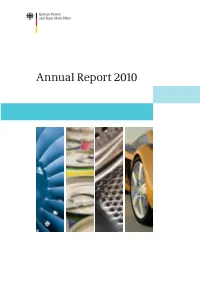

Annual Report 2010 at a Glance

Annual Report 2010 At a glance Industrial property rights 2009 2010 Changes in % Patents Applications 1 59,583 59,245 - 0.6 Concluded examination procedures 32,074 32,799 + 2.3 (final) - with patent grant 2 14,431 13,718 - 4.9 Stock 3 133,613 128,091 - 4.1 Trade marks Applications (national and international) 74,822 74,297 - 0.7 National marks Applications 69,069 69,072 + 0.0 Concluded examination procedures 73,054 70,962 - 2.9 - with registration 49,817 48,794 - 2.1 Stock 778,008 773,744 - 0.5 International marks Requests for grant of protection in Germany 5,753 5,225 - 9.2 Grants of protection 5,796 4,716 - 18.6 Utility models Applications 17,306 17,005 - 1.7 Concluded examination procedures 16,568 18,334 + 10.7 - with registration 13,916 15,476 + 11.2 Stock 96,909 95,598 - 1.4 Designs Designs applied for 44,714 47,188 + 5.5 Concluded examination procedures 37,311 49,865 + 33.6 - with registration 35,431 47,951 + 35.3 Stock 279,916 280,085 + 0.1 1 Patent applications at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA) and PCT patent applications upon their entry into the national phase 2 Including patents in respect of which an opposition was filed under Section 59 Patent Act. 3 Including patents granted by the European Patent Office with effect in the Federal Republic of Germany, a total of 525,882 patents were valid in Germany in 2010. Budget 2009 2010 Changes German Patent and Trade Mark Office and Federal Patent Court in % per million € Income 293.3 301.7 + 2.9 Expenditure 244.6 236.7 - 3.2 of which for personnel 133.1 138.8 + 4.3 -

Compulsory License Proceedings in Germany the Raltegravir and Alirocumab Cases Dr

Compulsory License Proceedings In Germany The Raltegravir and Alirocumab Cases Dr. Fritz Lahrtz [email protected] December 2019 . Overview over the Shionogi (Raltegravir) case . Legal requirements for compulsory license proceedings in Germany . The second compulsory license case: The Alirocumab (Praluent) Case . Lessons for Patentees and Third Parties December2019 Dr. Fritz Lahrtz 2 How works HIV? December2019 Dr. Fritz Lahrtz 3 The Shionogi-Case (1) . EP1422218B1 was granted in March 2012 and was supposed to expire in 2022 . An opposition was filed by MSD . The patent was upheld by the Opposition Division in March 2015 . Accelerated appeal proceedings were requested by Shionogi . The patent was revoked by the TBA in October 2017 due to added matter (Art. 123 (2) EPC) December2019 Dr. Fritz Lahrtz 4 The Shionogi-Case (2) . Claim 1 of EP1422218 B1 as upheld by the OD: December2019 Dr. Fritz Lahrtz 5 The Shionogi Case (3) . MSD sells Isentress, a medicament containing Raltegravir . No dispute in Germany that Raltegravir falls under claim 1 of EP1422218B1 . Negotiations were initiated by Shionogi in 2012 . An infringement law suit against MSD was filed by Shionogi in August 2015 . MSD filed a request for a compulsory license in January 2016 and a request for a preliminary injunction for a compulsory license in June 2016 December2019 Dr. Fritz Lahrtz 6 The Shionogi Case (4) . The hearing on the preliminary injunction before the German Federal Patent Court took place in August 2016 . The appeal hearing before the German Supreme Court took place in July 2017 . The hearing in the case on the merits took place in November 2017.