Open Source Software Licenses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easy As Abc: Categorizing Open Source Licenses

EASY AS ABC: CATEGORIZING OPEN SOURCE LICENSES Andrew T. Pham1, Matthew B. Weinstein2, Jamie L. Ryerson3 With more than 180,000 open source projects available and its more than 1400 unique licenses, the complexity of deciding how to manage open source usage within “closed-source” commercial enterprises have dramatically increased.4 Because of the complexity and risks associated with open source—where source code is made freely available for all to review, edit, and use—many closed-source commercial enterprises discourage or prohibit use of open source; a common and short-sighted practice. With a proper open source management framework, open source can be an invaluable resource, and its risks can be understood, managed and controlled. This article proposes a simple, consistent and effective open source categorization and management system to enable a peaceful coexistence between open source and closed-source codes. Free and open source software (“FOSS” or collectively “open source”) is a valuable tool, but one that must be understood to be used effectively. The litany of risks associated with use of open source include: having to release a derivative product incorporating open source under the same open source license; incorporating code that infringes a patent; violating an open source license’s attribution requirements; and a lack of warranties and indemnities. Given the extensive investment of time, money and resources that goes into product development, it comes as no This article is an edited version of the original, which dealt not only with categorizing open source licenses but also a wider array of issues associated with implementing an open source policy. -

An Introduction to Software Licensing

An Introduction to Software Licensing James Willenbring Software Engineering and Research Department Center for Computing Research Sandia National Laboratories David Bernholdt Oak Ridge National Laboratory Please open the Q&A Google Doc so that I can ask you Michael Heroux some questions! Sandia National Laboratories http://bit.ly/IDEAS-licensing ATPESC 2019 Q Center, St. Charles, IL (USA) (And you’re welcome to ask See slide 2 for 8 August 2019 license details me questions too) exascaleproject.org Disclaimers, license, citation, and acknowledgements Disclaimers • This is not legal advice (TINLA). Consult with true experts before making any consequential decisions • Copyright laws differ by country. Some info may be US-centric License and Citation • This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). • Requested citation: James Willenbring, David Bernholdt and Michael Heroux, An Introduction to Software Licensing, tutorial, in Argonne Training Program on Extreme-Scale Computing (ATPESC) 2019. • An earlier presentation is archived at https://ideas-productivity.org/events/hpc-best-practices-webinars/#webinar024 Acknowledgements • This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR), and by the Exascale Computing Project (17-SC-20-SC), a collaborative effort of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Nuclear Security Administration. • This work was performed in part at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725. • This work was performed in part at Sandia National Laboratories. -

Open Source Software Notice

Open Source Software Notice This document describes open source software contained in LG Smart TV SDK. Introduction This chapter describes open source software contained in LG Smart TV SDK. Terms and Conditions of the Applicable Open Source Licenses Please be informed that the open source software is subject to the terms and conditions of the applicable open source licenses, which are described in this chapter. | 1 Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Open Source Software Contained in LG Smart TV SDK ........................................................... 4 Revision History ........................................................................................................................ 5 Terms and Conditions of the Applicable Open Source Licenses..................................................................................... 6 GNU Lesser General Public License ......................................................................................... 6 GNU Lesser General Public License ....................................................................................... 11 Mozilla Public License 1.1 (MPL 1.1) ....................................................................................... 13 Common Public License Version v 1.0 .................................................................................... 18 Eclipse Public License Version -

The Copyleft Paradox Open Source Compatibility Issues and Legal Risks

Central IP Service the copyleft paradox open source compatibility issues and legal risks Brussels, 30/09/2015 Stefano GENTILE EC.JRC Central IP Service contents 2 open source philosophy characteristics of copyleft compatibility between multiple copyleft licences the 'copyleft paradox' examples of incompatible licences legal risks related to the use of OSS case law: a word from US disputes enforcement instruments conclusions Central IP Service open source philosophy 3 OPEN use copyright to SOURCE use accessnot just copy to source modify code distribute essential […] for society as a whole because they promote social solidarity—that is, . (gnu.org) Central IP Service copyleft rationale 4 COPYLEFT source code method © merged c pyleftconceived licence with static link effect effects on dynamic link downstream distribution of derivativeworks Central IP Service copyleft paradox 5 COPYLEFT copyleft proliferation ☣ incompatible viral terms good code mishmash practice goneviruses respecting one licence would bad result: defeats devised to forbid restrictions to sharing the very results in creating purpose “ ” of copyleft Central IP Service examples 6 source bsd COPYLEFT lgpl OSS licence type non-copyleft source weak copyleft mixing strong copyleft lgpl copyleft flexible copyleft with your own gpl source available transfer instr. lgpl any partly copyleft gpl source eupl copyleft none lgpl gpl source eupl epl Central IP Service cross-compatibility 7 COPYLEFT note: this is just a 1vs1 licence matrix… Central IP Service legal risks 8 misappropriation (very upsetting) OPEN SOURCE source code is not made available other condition not respected (e.g. incl. copy of the licence) copyleft conflicts commonmost the result is a using open …so, what are the consequences and sourcesoftware what the remedies? Central IP Service open source disputes 9 Jacobsen v. -

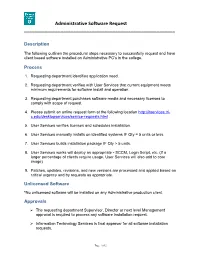

Administrative Software Procedure Explained

Administrative Software Request __________________________________________________________ Description The following outlines the procedural steps necessary to successfully request and have client based software installed on Administrative PC’s in the college. Process 1. Requesting department identifies application need. 2. Requesting department verifies with User Services that current equipment meets minimum requirements for software install and operation. 3. Requesting department purchases software media and necessary licenses to comply with scope of request. 4. Please submit an online request form at the following location http://itservices.tri- c.edu/desktopservices/service-requests.html . 5. User Services verifies licenses and schedules installation. 6. User Services manually installs on identified systems IF Qty = 5 units or less. 7. User Services builds installation package IF Qty > 5 units. 8. User Services works will deploy as appropriate - SCCM, Login Script, etc. (If a larger percentage of clients require usage, User Services will also add to core image) 9. Patches, updates, revisions, and new versions are processed and applied based on critical urgency and by requests as appropriate. Unlicensed Software *No unlicensed software will be installed on any Administrative production client. Approvals The requesting department Supervisor, Director or next level Management approval is required to process any software installation request. Information Technology Services is final approver for all software installation requests. Page 1 of 2 Administrative Software Request __________________________________________________________ ITS User Services Notes regarding Software Licenses) The only type of software that you can use legally without a license is software you write for your own use. All others require some type of license from the author and using any of them without a valid license is illegal as well as taking a risk that you and/or the college may be sued for damages. -

The Copyleft Movement: Creative Commons Licensing

Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture Volume 26 (2007) No. 3 IN THIS ISSUE The Copyleft Movement: Creative Commons Licensing Sharee L. Broussard, MS APR Spring Hill College AQUARTERLY REVIEW OF COMMUNICATION RESEARCH ISSN: 0144-4646 Communication Research Trends Table of Contents Volume 26 (2007) Number 3 http://cscc.scu.edu The Copyleft Movement:Creative Commons Licensing Published four times a year by the Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture (CSCC), sponsored by the 1. Introduction . 3 California Province of the Society of Jesus. 2. Copyright . 3 Copyright 2007. ISSN 0144-4646 3. Protection Activity . 6 4. DRM . 7 Editor: William E. Biernatzki, S.J. 5. Copyleft . 7 Managing Editor: Paul A. Soukup, S.J. 6. Creative Commons . 8 Editorial assistant: Yocupitzia Oseguera 7. Internet Practices Encouraging Creative Commons . 11 Subscription: 8. Pros and Cons . 12 Annual subscription (Vol. 26) US$50 9. Discussion and Conclusion . 13 Payment by check, MasterCard, Visa or US$ preferred. Editor’s Afterword . 14 For payments by MasterCard or Visa, send full account number, expiration date, name on account, and signature. References . 15 Checks and/or International Money Orders (drawn on Book Reviews . 17 USA banks; for non-USA banks, add $10 for handling) should be made payable to Communication Research Journal Report . 37 Trends and sent to the managing editor Paul A. Soukup, S.J. Communication Department In Memoriam Santa Clara University Michael Traber . 41 500 El Camino Real James Halloran . 43 Santa Clara, CA 95053 USA Transfer by wire: Contact the managing editor. Add $10 for handling. Address all correspondence to the managing editor at the address shown above. -

GNU / Linux and Free Software

GNU / Linux and Free Software GNU / Linux and Free Software An introduction Michael Opdenacker Free Electrons http://free-electrons.com Created with OpenOffice.org 2.x GNU / Linux and Free Software © Copyright 2004-2007, Free Electrons Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 license http://free-electrons.com Sep 15, 2009 1 Rights to copy Attribution ± ShareAlike 2.5 © Copyright 2004-2007 You are free Free Electrons to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work [email protected] to make derivative works to make commercial use of the work Document sources, updates and translations: Under the following conditions http://free-electrons.com/articles/freesw Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Corrections, suggestions, contributions and Share Alike. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license translations are welcome! identical to this one. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. License text: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/legalcode GNU / Linux and Free Software © Copyright 2004-2007, Free Electrons Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 license http://free-electrons.com Sep 15, 2009 2 Contents Unix and its history Free Software licenses and legal issues Free operating systems Successful project highlights Free Software -

Open Source Advising at Scale

Open Source Advising at Scale Justin C. Colannino Senior Attorney, Microsoft FINOS June 8, 2020 The Internet The opinions in this presentation are those of the presenter, not Microsoft or its affiliates. Agenda Open Source Open Source Law Counseling Refresher @ Scale Definition & Making calls without How to advise 60,000 License Archetypes (much) caselaw. developers for millions of use cases The Open Source Stack For Lawyers Economic Political Social Legal Technical A Counseling Framework Economic Political Social Legal Technical Commodity Custom What Is A License? Permission Permission (usually subject to conditions or obligations) Open Source: Permissions & Conditions or Obligations Right to Use, Copy, Modify, and Distribute (FSF – Four Freedoms) Must Meet Conditions or Obligations Typical: provide notice and/or provide source License Archetypes Ultra Permissive Permissive Increasing Obligations Weak Copyleft Copyleft Network Copyleft Open Source License Archetypes Ultra Permissive • Goal: Maximum Rights, NO Obligations (WTFPL, Unlicense, CC0) Permissive • Goal: Maximum Rights, Minimal Obligations • Distribution Triggers Attribution Obligation (MIT, BSD, Apache 2.0) Weak Copyleft • Goal: Preserve Freedom In A “Core” • Distribution Triggers Attribution Obligation & Source Code Obligation (EPL?, LGPL, MPL) Copyleft • Goal: Preserve Downstream Rights • Distribution Triggers Attribution Obligation & Source Code Obligation (GPL) Network Copyleft • Goal: Extend Copyleft to Network Services • Network Interaction Triggers Attribution Obligation -

Open Source, Copyright, Copyleft Open

Open Source, Copyright, Copyleft http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/ To copyleft a program, we first state that it is copyrighted; then we add distribution terms, which are a legal instrument that gives everyone the rights to use, modify, and redistribute the program's code or any program derived from it but only if the distribution terms are unchanged. Thus, the code and the freedoms become legally inseparable. Proprietary software developers use copyright to take away the users' freedom; we use copyright to guarantee their freedom. That's why we reverse the name, changing “copyright” into “copyleft.” CPS 82, Fall 2008 12.1 CPS 82, Fall 2008 12.2 Open Source, www.opensource.org Open Source licenses 1. Free Redistribution: can’t force, can’t prevent sale Copyleft licenses compared to free licenses 2. Source code: must be available, cheap or free Copyleft is “viral”, requires redistribution to be 3. License to modify, redistribution with same terms the same or similar 4. Integrity of author’s source (patchable, versioning) Free licenses have no downstream restrictions 5. No discrimination against persons or groups 6. No discrimination against fields of endeavor GPL is the Gnu Public License 7. Distribution “no strings”, no further licensing Currently v3, which is a complex, legal license 8. License not bound to whole, part redistribution ok X11 or BSD or Apache 9. No further restrictions, e.g., cannot require open All are free/open, but not viral, e.g., may permit commercial or proprietary products 10. Technology neutral CPS 82, Fall 2008 12.3 CPS 82, Fall 2008 12.4 LGPL: Lesser (nee Library) GPL Freedom Proprietary software developers, seeking to deny But we should not listen to these temptations, the free competition an important advantage, will because we can achieve much more if we stand try to convince authors not to contribute libraries to together. -

Open Source Software Licenses

Open Source Software Licences User Guide If you are working on a piece of software and you want to make it open source (i.e. freely available for others to use), there are questions you may need to consider, for example, whether you need a licence and why; and if so, how to choose a licence. This guide will help with those questions so that you have a better idea of what you need for your particular project. What is Open Source Software? ......................................................................................................... 1 Why do I need a licence for Open Source software? .......................................................................... 1 How do I choose a license? ................................................................................................................. 2 What if I have dependencies or my work is a derivative? .................................................................. 5 Combined Works and Compatibility ................................................................................................... 5 What if I want to change licenses? ..................................................................................................... 6 What if my software is protected by a patent? .................................................................................. 6 Can I commercialise Open Source Software? ..................................................................................... 6 Who should I speak to if I need help? ................................................................................................ -

Copy, Rip, Burn : the Politics of Copyleft and Open Source

Copy, Rip, Burn Berry 00 pre i 5/8/08 12:05:39 Berry 00 pre ii 5/8/08 12:05:39 Copy, Rip, Burn The Politics of Copyleft and Open Source DAVID M. BERRY PLUTO PRESS www.plutobooks.com Berry 00 pre iii 5/8/08 12:05:39 First published 2008 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © David M. Berry 2008 The right of David M. Berry to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 2415 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 2414 2 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. The paper may contain up to 70% post consumer waste. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton Printed and bound in the European Union by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Berry 00 pre iv 5/8/08 12:05:41 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix Preface x 1. The Canary in the Mine 1 2. The Information Society 41 3. -

Juridische Aandachtspunten Bij Het Gebruik Van Open Source Software

Juridische aandachtspunten bij het gebruik van Open Source Software [email protected] 1 Inhoud Achtergrond en open source definitie Voorbeelden open source software en licenties Welke licentie is van toepassing? Enkele bepalingen uitgelicht Praktijktips 2 Technische achtergrond 3 Conceptuele achtergrond 4 Open source definitie 1. De licentie mag niemand verbieden de software gratis weg te geven óf te verkopen. 2. De broncode moet met de software meegeleverd worden of vrij beschikbaar zijn. 3. Wederverspreiding van afgeleide werken en aangepaste versies van de software moet toegestaan zijn. 4. Licenties mogen vereisen dat aanpassingen alleen als patch verspreid worden. 5. De licentie mag niet discrimineren tegen gebruikers(groepen). 6. De licentie mag niet discrimineren tegen gebruiksomgeving van de software. 7. De rechten verbonden aan het programma moeten opgaan voor iedereen aan wie het programma gedistribueerd wordt. 8. De rechten verbonden aan het programma moeten niet afhangen van softwaredistributies waarvan de software een onderdeel is. 9. De licentie mag niet verlangen dat andere software die samen met de software verspreid wordt onder dezelfde licentie valt. 10. Geen van de bepalingen van de licentie mag slaan op een bepaalde technologie of interface-stijl. 5 Voorbeelden Apache License, 2.0 BSD licenses GNU General Public License (GPL) GNU Library or "Lesser" General Public License (LGPL) MIT license Mozilla Public License 1.1 (MPL) Common Development and Distribution License Common Public License 1.0 Eclipse Public License