1 Personal Details Description of Module Subject Name Philosophy Paper Name Ethics-1 Module Name/Title Bhagavad Gītā: the Dial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Master Plan and Zoning Regulations for Greater Tezpur -2031

REVISED MASTER PLAN AND ZONING REGULATIONS FOR GREATER TEZPUR -2031 PREPARED BY DISTRICT OFFICE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM TEZPUR: ASSAM SCHEDULE a) Situation of the Area : District : Sonitpur Sub Division : Tezpur Area : 12,659Hect. Or 126.60 Sq Km. TOWN & VILLAGES INCLUDED IN THE REVISED MASTER PLAN AREA FOR GREATER TEZPUR – 2031 MOUZA TOWN & VILLAGES Mahabhairab Tezpur Town & 1. Kalibarichuk, 2. Balichapari, 3. Barikachuburi, 4. Hazarapar Dekargaon, 5. Batamari, 6. Bhojkhowa Chapari, 7. Bhojkhowa Gaon, 8. Rajbharal, 9. Bhomoraguri Pahar, 10. Jorgarh, 11. Karaiyani Bengali, 12. Morisuti, 13. Chatai Chapari, 14. Kacharipam, 15. Bhomoraguri Gaon, 16. Purani Alimur, 17. Uriamguri, 18. Alichinga Uriamguri. Bhairabpad 19. Mazgaon, 20. Dekargaon, 21. Da-parbatia, 22. Parbatia, 23. Deurigaon, 24. Da-ati gaon, 25. Da-gaon pukhuria, 26. Bamun Chuburi, 27. Vitarsuti, 28. Khanamukh, 29. Dolabari No.1, 30. Dolabari No.2, 31. Gotlong, 32. Jahajghat 33. Kataki chuburi, 34. Sopora Chuburi, 35. Bebejia, 36. Kumar Gaon. Halleswar 37. Saikiachuburi Dekargaon, 38. Harigaon, 39. Puthikhati, 40. Dekachuburi Kundarbari, 41. Parowa gaon, 42. Parowa TE, 43. Saikia Chuburi Teleria, 44. Dipota Hatkhola, 45. Udmari Barjhar, 46. Nij Halleswar, 47. Halleswar Devalaya, 48. Betonijhar, 49. Goroimari Borpukhuri, 50. Na-pam, 51. Amolapam, 52. Borguri, 53. Gatonga Kahdol, 54. Dihingia Gaon, 55. Bhitar Parowa, 56. Paramaighuli, 57. Solmara, 58. Rupkuria, 59. Baghchung, 60. Kasakani, 61. Ahatguri, 62. Puniani Gaon, 63. Salanigaon, 64. Jagalani. Goroimari 65. Goroimari Gaon, 66. Goroimari RF 1 CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION Tezpur town is the administrative H/Q of Sonitpur Dist. Over the years this town has emerged as on the few major important urban centers of Assam & the North Eastern Region of India. -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga

Orissa Review * October - 2004 The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga Pradeep Kumar Gan Shaktism, the cult of Mother Goddess and vast mass of Indian population, Goddess Durga Shakti, the female divinity in Indian religion gradually became the supreme object of 5 symbolises form, energy or manifestation of adoration among the followers of Shaktism. the human spirit in all its rich and exuberant Studies on various aspects of her character in variety. Shakti, in scientific terms energy or our mythology, religion, etc., grew in bulk and power, is the one without which no leaf can her visual representation is well depicted in stir in the world, no work can be done without our art and sculpture. It is interesting to note 1 it. The Goddess has been worshipped in India that the very origin of her such incarnation (as from prehistoric times, for strong evidence of Durga) is mainly due to her celestial mount a cult of the mother has been unearthed at the (vehicle or vahana) lion. This lion is usually pre-vedic civilization of the Indus valley. assorted with her in our literature, art sculpture, 2 According to John Marshall Shakti Cult in etc. But it is unfortunate that in our earlier works India was originated out of the Mother Goddess the lion could not get his rightful place as he and was closely associated with the cult of deserved. Siva. Saivism and Shaktism were the official In the Hindu Pantheon all the deities are religions of the Indus people who practised associated in mythology and art with an animal various facets of Tantra. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Hengul-Haital: Traditional Colours of Medieval Assam

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Hengul-Haital: Traditional Colours of Medieval Assam Chayanika Borah Department of Assamese, Gogamukh College, Dhemaji, Assam Devaprotim Hazarika Department of Assamese, N. N. Saikia College, Titabar, Jothat, Assam Abstract Assam, one of states of India, has been very rich in art and culture since ancient times. The history of Assamese fine arts can be traced back to the middle ages period. Basically, kingdoms and Satras were the main centre of attraction where fine arts had been practiced. Generally, the pictures found in manuscripts written in Sanchipat and Tulapaat were the sign of evidences of the existence of art education in Assam. In those arts, the ability to use the perfect combination of colours was really appreciated. The artists used mainly two colours in their pictures, they were: Hengul and Haithal to enhance the aesthetic beauty of those artistic creations. Besides, the exploitation of these two colours Hengul and Haithal was also evident in Shankardeva’s period. These two colours were seen in furniture, different instruments used in music, Bhaonas etc., those found in Shankardeva’s Satras, Naamghars. Hengul and Haital represent especially the characteristics of the middle Assamese period. These two colours gained popularity due to its durability and preservative qualities. The present paper is attempted to discuss mainly the identity, procedure of production, practical application those colours in the creation arts of the middle age period of Assam. Keywords: Assam, Assamese, Colour, Hengul, Haital, Shankardeva, Traditional, Introduction Assam, one of the states of Northeast India, has a unique and valuable cultural heritage. -

BY: Chitralekha Devi Dasi

BY: Chitralekha Devi Dasi Fearful for the Future of ISKCON Nov 16, 2012 — USA (SUN) — Further discussion with Ajamila das on the issue of Female Diksa Gurus. Dear Respected Ajamila Prabhu, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. My comments below. You wrote: On Fri, Nov 9, 2012 at 12:33 PM, Ajamila (das) ACBSP (Goloka Books - UK) wrote: Dear Citralekha d.d. Hare Krishna!! Jaya Srila Prabhupada! Your letter is an eye opener for sure, showing the perspective from a woman as yourself that a man cannot so easily see, your summary said it all: >> To conclude, from this soul's (in a female body) point of view this whole >> idea of female diksha guru is the essence of stupidity, a disaster for >> ISKCON and Lord Caitanya's preaching mission. I agree with you that female diksha gurus for ISKCON would be a disaster IF the wrong women are allowed to initiate. It appears you have not met any woman sufficiently qualified to be diksha guru, but have you met every woman in ISKCON? I'm not going to name anyone but if betting was not against the regulative principles I would bet my bottom dollar that I could find at least a hand full in the big ISKCON world who would be sufficiently qualified and would honour ISKCON and Lord Chaitanya's preaching movement. We don't need a Gangamata lime liberated soul, we only need a woman who has good sadhana, has attained nistha, is learned, a preacher, and can match in their own way what our existing male gurus in good standing are doing. -

Placement Brochure of Excellent Design and Quality

PLACEMENT DEPARTMENTBROCHURE OF MASS COMMUNICATION AND JOURNALISM B A T C H 2014-16 messages From the Vice Chancellor Best Wishes Communication with each other, communication with mass, and communication through print and electronic media are some of the very important attributes that any individual would love to possess in oneself. These and many skills including photography-videography, acts and plays including street plays for public convenience and awareness of contemporary relevant topics are the parts of skills that the department of mass Communication and Journalism imparts to our graduates. In addition, the department is actively engaged in research of contemporary importance maintaining a vibrant teaching and research culture as evident from the number of research Scholars working in the department for their PhD. Some good publications have also been emerging out of the research endeavour. This is one of the oldest departments of our university with its students being very intelligent, enthusiastic, pro-active with a special aptitude in their chosen domain. Thirteen batches of students have already graduated and they are placed well. The 14th batch of students shall be graduating in another 6/7 months and now getting ready to be placed. In addition to their knowledge, many of them are very good in terms of soft skills and co-curricular activities, as evident by many accolades that they have earned while they are studying in this university. Their enthusiasm, proficiency, aptitude, skill and aspirations give credence to the contention that the students graduating now deserve positions in organizations looking for smart and forward looking professionals. The book that is prefaced by my note provides all relevant information about the 14th batch of our MCJ students. -

Tezpur: a Historical Place of Tourism in Assam Manik Chandra Nath Assistant Professor, Dept

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN: 2455-0620 Volume - 5, Issue - 9, Sept – 2019 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal with IC Value: 86.87 Impact Factor: 6.497 Received Date: 19/09/2019 Acceptance Date: 30/09/2019 Publication Date: 30/09/2019 Tezpur: A Historical place of Tourism in Assam Manik Chandra Nath Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, Telahi Tuwaram Nath College, Khaga, Lakhimpur, Assam-787052 (India) Email – [email protected] Abstract: The 21st century make its development in all sphere i.e., industry, craft, education, science and technology, literature so on. In the sense of eco-tourism, the Government of India as well as Government of Assam has taken some very positive plan and programme to emphasis on the particular sectors. The development of tourism industry can contribute lots of hope to our socio-economic development especially in the North East Region. In Assam, the government has laid foundation to promote eco-tourism with the programme ‘atulaniya asom’. In recent period tourism is becoming a very profitable industry than other industry. By the eco-tourism development the socio-culture, socio-economic life of the people has also gradually changed. Tourism is popularly considered as travel for recreation, leisure or business purposes. Tezpur is a very beautiful tourist place of development in the concern of eco-tourist site in Assam. Historically, Tezpur has own identity and present days it become the centre place of tourist. Therefore, the attempt of the paper is to find positive way to extend our eco- tourism in (Thisthe side is andfor cornerexample of the - Authors globe. -

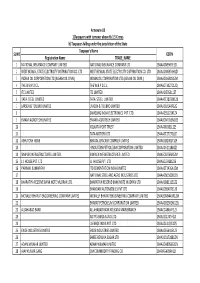

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Ministry of Home Affairs Telephone List Home

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS TELEPHONE LIST ******** HOME MINISTER’S OFFICE NAME&DESIGNATION R. NO. OFFICE I.Com RESIDENCE/EMAIL 104 23092462 - 23793881 RAJNATH SINGH 23094686 23014184 HOME MINISTER 23017256 (PH) 23017580 (PH)(F) NITESH KUMAR JHA 105 23092462 414 - PS To HM 23094686 23094221(FAX) AMRENDRA KUMAR 107 23092462 414 - SENGAR 23094686 OSD TO HM 23092113(FAX) HARI KRISHNA PALIWAL 106 23094246 416 - ADVISOR KRISHNENDRA PRATAP 103-A 23092462 414 - SINGH 23094686 OSD TO HM 23092979 (FAX) PRABHAT KUMAR TRIPATHI 103-A 23092462 414 - ADDL. PS TO HM 23094686 23092979 (FAX) AMARENDRA TIWARI 103-A 23092462 414 - APS TO HM MINISTER OF STATE (H) OFFICE HANSRAJ GANGARAM 101 23092870 - 23717121 AHIR 23092595 MINISTER OF STATE(H) SUSHIL PAL 198 23092595 270 - PS TO MOS(H) 23094896(FAX) DR.RAJESH ADPAWAR 196-A 23092870 270 - ADDL.PS TO MOS(H) 23094896(FAX) MINISTER OF STATE (R) OFFICE KIREN RIJIJU 127 23092073 - 23017957 MINISTER OF STATE 23094054 23017965 VIKAS ANAND 127-B 23092073 318 26131278 PS TO MOS(R) 23094054 23093549(FAX) ANUPAM YADAV 125-B 23092073 ̘318 26894815 OSD TO MOS(R) 23094495 23093549(FAX) SONAM GECHEN AGOLA 126 23092073 318 ADDL. PS TO MOS(R) 23094054 23094495 23093549(FAX) SHIV KUMAR 125-B 23092073 318 APS TO MOS(R) 23094054 23093549(FAX) AMIT JAIN 126-C 23092073 318 PS, OFFICE OF MOS(R) 23094054 - 23093549(FAX) HOME SECRETARY’S OFFICE RAJIV GAUBA 113 23092989 - - HOME SECRETARY 23093031 23093003 (FAX) SUNIL KR. DHAWAN 113-A 23092989 254 25055632 PR. STAFF OFFICER TO 23093031 HS SATISH KARGETI 113-A 23092989 215 26104456 PPS TO HS 23093031 254 SECRETARY (BORDER MANAGEMENT) OFFICE 124 23092440 369 [email protected] SECRETARY (BM) 23092717 (FAX) DEVENDRA SINGH 122 23092440 369 - PPS TO SECRETARY (BM) 122 23092440 369 - PS TO SECRETARY (BM) SECRETARY (DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL LANGUAGE) PRABHAS KUMAR JHA NDCC-II 23438266 - [email protected] SECRETARY (DOL) A wing 23438267 3rd floor KAVITA HANDA NDCC-II 23438266 - Sr. -

Manil Suri.Pdf

This work is on a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. Access to this work was provided by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) ScholarWorks@UMBC digital repository on the Maryland Shared Open Access (MD-SOAR) platform. Please provide feedback Please support the ScholarWorks@UMBC repository by emailing [email protected] and telling us what having access to this work means to you and why it’s important to you. Thank you. Manil Suri From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search Manil Suri Born July 1959 Bombay, India Occupation Novelist, mathematician Nationality Indian, American Website manilsuri.com Manil Suri (born July 1959) is an Indian-American mathematician and writer of a trilogy of novels all named for Hindu gods. His first novel, The Death of Vishnu (2001), which was long-listed for the 2001 Booker Prize, short-listed for the 2002 PEN/Faulkner Award and won the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize that year. Since then, he has published two more novels, The Age of Shiva (2008) and The City of Devi (2013), completing the trilogy. Contents • 1Biography • 2Books • 3Further reading • 4Notes • 5External links Biography[edit] Suri was born in Bombay, the son of R.L. Suri,[1] a Bollywood music director, and Prem Suri, a schoolteacher. He attended the University of Bombay before moving to the United States, where he attended Carnegie Mellon University.[2] He received a Ph.D. in mathematics in 1983, and became a mathematics professor at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. -

4. Gita Bhashyam

Sincere Thanks to: Sri Oppiliappan Koil V. Sadagopan Swamy for releasing this eBook in the Godha Series at Sadagopan.Org SrI: Art Work by Sau. R. Chitralekha ” fi À Introduction to tAtparya CandrikA - Bhagavad Gita śAstra avatArikA Dear RasikAs of Srimad Bhagavad GitA: On behalf of the Members of Sri Hayagreeva likhita kaimkarya ghoshThI, it is my bhAgyam as its SampAtakar to release the First of the nineteen e- books as the special samarpNam during the year long celebration of SvAmi Vedanta Desikan’s avatAram at Tooppul in 1268 C.E. The focus of this set of e-books is on Bhagavad Ramanuja’s GitA BhAshyam and SvAmi Desikan’s Commentary on that BhAshyam named tAtparya CandrikA. We will commence this series with an introduction today and seek GitAcAryan’s blessings to have Kaimkarya pUrti on the 2018 PurattAsi SrAvaNam day. There are many BhAshyams for Srimad Bhagavad GitA. From the ViśishTAdvaita darśanam point of view, SvAmi Alavandar’s GitArtha sangraham, Bhagavad Ramanuja’s GitA BhAshyam based on the Sri sUkti of SvAmi Alavandar and SvAmi Desikan’s own GitA BhAshyam elaborating on Bhagavad Ramanuja’s GitA BhAshyam named “tAtparya CandrikA“ are the earliest BhAshyams and have provided the inspiration for subsequent Gita BhAshyams in Sanskrit, MaNipravALam, Kannada and Tamil. It is interesting to note that there are a few English translations and commentaries on GitA BhAshyam of AcArya Ramanuja, where as none exists until now for the word by word meanings and commentaries in English for the insightful GitA BhAshyam/tAtparya CandrikA of SvAmi Desikan Himself. Sri Hayagreeva likhita kaimkarya ghoshThI with the help of VidvAn Sri.