Literary Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diary of a West Country Physician, A.D. 1684-1726

Al vi r 22101129818 c Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Wellcome Library https://archive.org/details/b31350914 THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN IS A Obi,OJhJf ct; t k 9 5 *fay*/'ckf f?c<uz.s <L<rble> \\M At—r J fF—ojILlIJ- y 't ,-J.M- * - ^jy,-<9. QjlJXy }() * |L Crf fitcJlG-t t $ <z_iedl{£ AU^fytsljc<z.^ act Jfi :tnitutor clout % f §Ve* dtrrt* 7. 5^at~ frt'cUt «k ^—. ^LjHr£hur IW*' ^ (9 % . ' ' ?‘ / ^ f rf i '* '*.<,* £-#**** AT*-/ ^- fr?0- I&Jcsmjl. iLM^i M/n. Jstn**tvn- A-f _g, # ««~Hn^ &"<y muy/*£ ^<u j " *-/&**"-*-■ Ucn^f 3:Jl-y fi//.XeKih>■^':^. li M^^atUu jjm.(rmHjf itftLk*P*~$y Vzmltti£‘tortSctcftuuftriftmu ■i M: Oxhr£fr*fro^^^ J^lJt^ veryf^Jif b^ahtw-* ft^T #. 5£)- (2) rteui *&• ^ y&klL tn £lzJ£xH*AL% S. HjL <y^tdn %^ cfAiAtL- Xp )L ^ 9 $ <£t**$ufl/ Jcjz^, JVJZuil ftjtij ltf{l~ ft Jk^Hdli^hr^ tfitre , f cc»t<L C^i M hrU at &W*&r* &. ^ H <Wt. % fit) - 0 * Cff. yhf£ fdtr tj jfoinJP&*Ji t/ <S m-£&rA tun 9~& /nsJc &J<ztt r£$tr*kt.bJtVYTU( Hr^JtcAjy£,, $ev£%y£ t£* tnjJuk^ THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN A.D. 1684-1726 Edited by EDMUND HOBHOUSE, M.D. ‘Medicines ac Musarum Cultor9 TRADE AGENTS: SIMPKIN MARSHALL, LTD. Stationers’ Hall Court, London, E.C.4 PRINTED BY THE STANHOPE PRESS, ROCHESTER *934 - v- p C f, ,s*j FOREWORD The Manuscripts which furnish the material for these pages consist of four large, vellum-bound volumes of the ledger type, which were found by Mr. -

The Poor in England Steven King Is Reader in History at Contribution to the Historiography of Poverty, Combining As It Oxford Brookes University

king&t jkt 6/2/03 2:57 PM Page 1 Alannah Tomkins is Lecturer in History at ‘Each chapter is fluently written and deeply immersed in the University of Keele. primary sources. The work as a whole makes an original The poor in England Steven King is Reader in History at contribution to the historiography of poverty, combining as it Oxford Brookes University. does a high degree of scholarship with intellectual innovation.’ The poor Professor Anne Borsay, University of Wales, Swansea This fascinating collection of studies investigates English poverty in England between 1700 and 1850 and the ways in which the poor made ends meet. The phrase ‘economy of makeshifts’ has often been used to summarise the patchy, disparate and sometimes failing 1700–1850 strategies of the poor for material survival. Incomes or benefits derived through the ‘economy’ ranged from wages supported by under-employment via petty crime through to charity; however, An economy of makeshifts until now, discussions of this array of makeshifts usually fall short of answering vital questions about how and when the poor secured access to them. This book represents the single most significant attempt in print to supply the English ‘economy of makeshifts’ with a solid, empirical basis and to advance the concept of makeshifts from a vague but convenient label to a more precise yet inclusive definition. 1700–1850 Individual chapters written by some of the leading, emerging historians of welfare examine how advantages gained from access to common land, mobilisation of kinship support, crime, and other marginal resources could prop up struggling households. -

Winter 2014 Newsletter.Vp

THE PARSON WOODFORDE SOCIETY WINTER 2014 NEWSLET TER No. 100 A NEW PRESIDENT It was with sadness that we learnt that Suzanne Custance has had to step down from the Presidency of the Society because of family ill-health. We hope to hear better news in future months. However, we are pleased to report that the Presidency has been offered to and accepted by Professor Richard Wilson. He has been a member of the Society since 1968. He is Emeritus Professor of Economic & Social History at the University of East Anglia, the co-author of Creating Paradise: The Building of the English Country House, 1660-1880, and co-editor of Norwich since 1550. His particular interests are in the history of brewing, textiles and the country house. He has written a number of articles for the Society’s Journal. DIARY VOLUME 11 A new edition of Volume 11 of the Diary, 1785-87, has been completed by Peter Jameson and is ready for despatch. It may be ordered from Mrs Jenny Alderson using the enclosed Order Form. FROLICS 2014 AND 2015 You can read a report of the very successful October Frolic in Norwich in the accompanying Journal. Next year’s Frolic will be in Wells, Somerset, based at the Swan Hotel where we stayed in 2007, between Friday 11th September and Sunday 13th September 2015. On the Saturday, we hope to visit Castle Cary and nearby locations associated with James Woodforde. Put these dates in your diary now! “THE FORTUNE TELLER” APPEAL In the Autumn mailing, an appeal was launched for “The Fortune Teller”, a large oil-painting by Samuel Woodforde, R.A., which the Society has purchased. -

Billingsley Fourty Shillings Apiece Item I Give Unto My Aforesayd Brother Mr

Descendants by Generation 7 Mar 2015 Katherine WHITLOCK (1622-1690) 1. Katherine WHITLOCK was born in 1622 in London, MDX.1 She died in 1690 in London.1 She married Thomas JORDAN. 1690: WILL OF KATHERINE (WHITLOCK) JORDEN In the name of God Amen I Katherine Jorden of London widdow being weake in body but of sound mind and memory (blessed be God doe make and ordaine this my last will and Testament And as touching the Temporall Estate wherewith God hath Graciously blessed mee I doe Will and devise the same as followeth Imprimus I give unto Doctor Samuell Annesly and to my brother Mr. John Whitlock the sume of one hundred pounds of lawfull oney of England to bee payd nto them within one yeare next after my decease Uppon trust in the in them .....ed that they or the survivour of them shall give and dispose the same to such and soe many poore Godly Ministers and in such proportions as I shall either in writeing under my hand or by word of mouth before witnesses nominiate and apppoint to receive the same within one yeare next after my decease And if any of these persons that I shall nominate dye before they have received the proportion by mee appointed them Then my said Trustees are to pay the same to such other person or persons in his or their stead as my sayd Trustees shall thinke fitt Item I further give to the said Doctor Annesley and my brother Whitlock the sume of Thirty pounds like money to bee payd them within the Time aforesayd uppon Trust that they or the Survivour of them doe likewise give and dispos of the same to such and soe -

JS Journal Sep 1956

• "^ X JOURNAL SEPTEMBER, 1956 J. S. Journal HOUSE MAGAZINE OF J. SAINSBUKY LTD. SEPTEMBER 1956 NEW SERIES, NO. 30 Contents 1-4 Ealing Converts to Self-Service . 1 The Charity of John Marshall .. 18 The Economic Power of the Retailer. 22 Portraiture at Collier Row . 28 Bacon Control .. 30 J.S. in Oxford 31 Peace with Plenty . 33 What the Well-fed Whale is Eating .. 44 Potters Bar Get Out and About .. 46 National Service News. Page iii of Cover Letters and contributions are invited from all members of J.S. Staff. Photographs of Staff Association activities will be particularly welcome. A fee of half a guinea will be paid for any photo graph by a member of J.S. Staff which is published OUR COVER PICTURE: in J.S. JOURNAL. Mary Ann Balm, daughter of one of 1-4 All communications should be sent to Haling's customers, The liditor, J.S. JOURNAL, waited cheerfully while Stamford 1 louse, Blackfriars, her mother shopped in London, S.H.I. the new store. The new self-service store at 1-4 Ealing High Street as it looks now that it is complete. 1-4 Ealing Converts to Self-service J.S. CONNECTIONS with Ealing date back to the opening of 15 Broadway in 1894. 130 Uxbridge Road, a small provision shop, was opened in 1902 followed by 87 Broadway in 1906. Our butcher shop at 126 Uxbridge Road was opened in 1920. Then in 1927 three small sites, 2, 3 and 4 High Street, Ealing, opened as a single shop under Mr. -

(2019), No. 9 1 Nephew Bill Goes to Sea in 1776

Nephew Bill Goes to Sea In 1776 the diarist James Woodforde left his comfortable college rooms here at New College and his family home at Ansford in Somerset, to take up his new post as rector of Weston Longville, a college living in Norfolk. He took with him for company his young nephew Bill, by then aged sixteen. Bill, however, found life in rural Norfolk lonely and rather tedious; he was not cut out to be a shooting and fishing country gentleman or the protégé of a clergyman, and he rapidly became very bored and truculent. Things came to a head two years later. On 11 May 1778 Parson Woodforde wrote the first of a series of troubling thoughts in his diary: ‘William was up in the Maids Room this morning, and Sukey was still abed—I think there is an intimacy between them.’ That may or may not have been an accurate fear; William himself later blacked-out the relevant entries when he inherited the diary,1 but the maidservant Sukey was indeed pregnant and left Weston parsonage later that summer, having named a local labourer as the father of her child. Nevertheless, after close questioning of his nephew and doing some arithmetic, Parson Woodforde remained uneasy. The whole business signalled the growing need to find Nephew Bill a career, preferably abroad. At that time, Britain was involved in the American War of Independence and the royal navy was desperate for able young men. Bill had already shown an interest in maritime matters while still in Somerset back in 1774, setting out (in a laborious copperplate hand) in a notebook the sort of information likely to be needed by a young man learning the business of a customs house—how to draw up lading bills correctly, how to borrow money (!), the rates payable for wharfage and lighterage, and so on. -

Agricultural Improvement in England and Wales and Its Impact on Government Policy, 1783-1801

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1977 Agricultural Improvement in England and Wales and Its Impact on Government Policy, 1783-1801. Mack Thomas Nolen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Nolen, Mack Thomas, "Agricultural Improvement in England and Wales and Its Impact on Government Policy, 1783-1801." (1977). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3076. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3076 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Winter Newsletter 2011.Vp

THE PARSON WOODFORDE SOCIETY WINTER 2011 NEWSLET TER No. 88 GEORGE BUNTING We are very sorry to announce the death of George Bunting, the President of our Society. On 30th October he died suddenly but peacefully at the age of 86, at his home in Hadspen, near Castle Cary. His funeral was held at St Leonard’s Church, Pitcombe, and conducted by the Rector of Bruton. The church was filled with George’s extensive family and many local people. Society members who attended included Martin Brayne, who read diary-extracts; Ann Williams; Suzanne Custance; Derek & Mollie Matthews; and Jenny & Peter Alderson. He is buried nearby in beautiful Somerset countryside which would have been well-known to James Woodforde. You can read an Obituary in the accompanying Journal. He will be greatly missed, and we send our condolences to his widow Mabs, and to his family. FROLIC 2012 – LONDON WEEKEND Some members were disappointed when our Chairman announced at Dorchester that the Committee was planning a Frolic in 2012 for one day only. So members will be happy to hear that we are now arranging a weekend Frolic in London, from Friday 31st August to Sunday 2nd September. We shall be resident in Bloomsbury, making visits to The Foundling Museum (see Woodforde’s Diary entry for 20th October 1793), the British Library and other local attractions. Please note the dates in your 2012 Diary now; booking details will be given in the Spring mailing. SUZANNE CUSTANCE STEPS DOWN Suzanne Custance, a descendant of Mr and Mrs Custance of the Diary, has been a Committee member for very many years, and for a considerable time she was the Secretary. -

GIPE-064937-Contents.Pdf

WOMEN :WORKERS i\l'fQ THE . ----..~ - INDUSTRIAL: .. , .............. .-,,-"'.......... :...-.~: ' ,I I • 'Il' ;,,_GMlilLinly "- i 111111111111 ? .! GlPE-PUN~931 i LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS STUDIES IN ECONOMIC. AND SOC~AL HISTORY Edit.d by R. H. TAWNEY AND EILEEN POWER WOMEN WORKERS AND THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLU TION, 1750-1850. By IVY PINCHBBCK, II.A. A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH CORN LAWS FROM 1660 TO 1846. By DONALD GllOVB BAllNDS, Professor of History in the University of Oregon. ANGLO-IRISH TRADE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY. By ADA KATHLEEN LONGFIELD, LL.B., M.A. ENGLISH l'RADE IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. EJilltl by M. POSTAN and EILEEN POWED. D.LIT. SOCIAL POLICY UNDER THE COMMONWEALTH AND PROTECTORATE. By MADGARET JAIl'BS, PH.D., Lecturer in History at the Royal Holloway College. THE RISE OF THE ENGLISH coAL INDUSTRY. By J. U. NBP, Associate-Professor iD the University of Chiea&,,_ WOM:E-N WORKERS ANn THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 175°-185° By IVY PINCHBECK, M.A. (Lon4.) LSCTURBR IN BCONOMIC BlSTOay AT BBDl'OllD COLLaO., (UNIVIIlISI1T OW LONDON) LONDON • GEORGE ROUTLEDGE &: SONS, LTD., BROADWAY JlOUSE I 611-74 CARTER LANE, E.o. 1930 X: '/~ ~ 3·14& CrD PRINTBD IN GRBAT BRITAIN BY TBB DBVONSHlRB PRBS8, TORQUAY TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHER PREFACE THIS book is an attempt to give an account of the conditions governing the lives of working women during ·the period I75O-I850. The fndustrial Revolution has been studied from many aspects, but so a r women's work during this period has not been the subject of any separate and detailed study. -

The Norfolk & Norwich

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Vol. 23 PART 3 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY, 1974-75 President: Mr. A. Bull, Berry Hall Cottage, Honingham. President-Elect: The Earl of Cranbrook, c.b.e., f.l.s., Great Glenham House, Saxmundham. Vice-Presidents: P. R. Banham, E. T. Daniels, K. C. Durrant, Dr. E. A. Ellis, R. Jones, M. J. Seago, Professor J. A. Steers, E. L. Swann, F. J. Taylor-Page General Secretary: R. E. Baker, 15 Southern Reach, Mulbarton, Telephone: Mulbarton 609 Assistant Secretary: (Membership and Publications): Miss E. M. Buttery, 5 Lynch Green, Hethersett. Assistant Secretary: (Minutes): K. B. Clarke, Decoy House, Browston, Great Yarmouth Excursion Secretary: Mrs. J. Robinson, 5 Southern Reach, Mulbarton Treasurer: D. A. Dorling, St. Edmundsbury, 6 New Road, Hethersett, Telephone: Norwich 810318 Assistant Treasurer: J. E. Timbers, The Nook, Barford, Norwich Editor: Dr. E. A. Ellis, Wheatfen Broad, Surlingham, Norwich Auditor: E. L. Swann, 282 Wootton Road, King’s Lynn, Norfolk Committee: ' Miss R. Carpenter, Miss A. de caux, Dr. A. Davy (University Representative) J. G. Goldsmith, C. Gosling, P. Lambley, Miss D. Maxey, Miss F. Musters, J. Secker, P. M. C. Stevens ORGANISERS OF PRINCIPAL SPECIALIST GROUPS Birds ( Editor of the Report): M. J. Seago, 33 Acacia Road, Thorpe, Norwich Mammals (Editor of the Report): J. Goldsmith, Department of Natural History, Castle Museum, Norwich Plants: E. A. Ellis and E. L. Swann Insects: K. C. Durrant, 18 The Avenue, Sheringham amphibia/ Reptiles: J. Buckley, 22 Aurania Avenue, Norwich Mollusca: R. E. Baker Editor: E. A. Ellis Editor: E. A. ELLIS CONTENTS Page Address, as read by the President, Miss Catherine Gurney, to the Members of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society at a meeting held in the Central Library Lecture Theatre, Norwich, December 4th, 1973 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ — 111 Norfolk Weather 1778-1802 as recorded by Reverend James Woodforde by J. -

Supporting 16,000 Cathedral and Church Buildings of the Church of England Contents

CATHEDRAL & CHURCH BUILDINGS DIVISION GRANTS REPORT 2020 Supporting 16,000 cathedral and church buildings of the Church of England CONTENTS Introduction 3 Divisional Projects 4 Our Funders 6 Grants for Conservation 8 Grants for the Conservation of Bells 8 Grants for the Conservation of Churchyard Structures 10 Grants for the Conservation of Clocks 11 Grants for the Conservation of Metalwork 12 Grants for the Conservation of Monuments 13 Grants for the Conservation of Organs 14 Grants for the Conservation of Paintings 15 Grants for the Conservation of Stained Glass 16 Grants for the Conservation of Textiles 17 Grants for the Conservation of Wall Paintings 18 Grants for the Conservation of Wooden Objects 20 Grants for Conservation Reports 21 Grants for Fabric Repairs 27 Grants for Programmes of Major Works 30 Conservation Committee Membership 35 COVER Munslow, St Michael (Diocese of Hereford) 15th-century stained glass depicting St Margaret of Antioch. Image courtesy of Jim Budd Stained Glass INTRODUCTION The resilience and innovative spirit of churches and cathedrals throughout the very difficult year of 2020 has been remarkable to witness, and a privilege to support. Despite church buildings having to close, initially for all purposes and in the later stages of the pandemic for all but a very limited range of purposes, we have seen an extraordinary growth in alternative forms of worship and community engagement. Many have moved services online, in some cases attracting congregations from all across the globe. And many thousands of churches continued to provide essential community support activities. The effectiveness of this was noted by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, in his 2021 Easter address: “I’ve lost count of the number of Church leaders and congregations from all denominations that have stepped up to support not only one another but also to support the whole local community, people of all faiths and none.” But we also know that for many churches 2020 was an incredibly challenging year. -

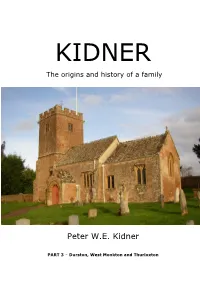

Peter W.E. Kidner

KIDNER The origins and history of a family Peter W.E. Kidner PART 3 – Durston, West Monkton and Thurloxton based on a A One-Name Study of KIDNER And its variants and aliases, namely - Ketenore, Kidenore, Ketnor, Kitnor, Kitner, Kydnor Peter Kidner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work © P.W.E. Kidner 1996-2005. Cover: St Giles, Thurloxton. Photo © Simon Kidner 2004 ii INTRODUCTION It has been said that nothing is certain in genealogy. Written records were often prepared long after the event and were based on oral accounts or on hearsay. Names were spoken and the writer wrote down what he heard - or thought he heard. Parish clerks were often poorly educated and easily confused. There was always scope for error! In drafting this study I have had two specific aims. The first and obvious aim has been to occupy my retirement years with something which has a great fascination for me and which, at the same time, seems to be constructive and of probable interest to others - the history of our family name. My second aim has been to carry on the research started by my father, William Elworthy Kidner, which occupied much of his later years. Although he studied the whole of our family history from the Conquest to the present century, he specialised in the medieval period. His research notes are comprehensive, detailed and accurate; and incorporate extracts and translations of all the more important source references. But he never attempted to put together a coherent sequence of events which could form the basis for a narrative account; nor did he pass on his findings to any but a few close friends and relatives.