Insights Into Hospital Discharge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarter 7 Duplicate Removal Process

Quarter 7 Duplicate Removal Process Guidance Total number of records submitted via the web tool (ie Stroke / All records (of any diagnosis) for patients who arrived at hospital TIA / Other) between 1 October 2012 and 31 December 2013 which were locked on the SINAP web tool by 21 January 2013. Number of stroke records submitted via the web tool As above, except that stroke was the diagnosis (as opposed to TIA/Other). Total number of records after cleaning (ie duplicate removals) Records assumed to be duplicates are those that have all of the following fields identical: hospital, date of patient arrival at hospital, gender, age and diagnosis. This may mean that some records that were not real duplicates are removed, but this is proportionally only a small number of those removed, whereas the vast majority will be duplicates. This has been identified as the most appropriate method for removing duplicate records. Percentage of records submitted included after cleaning The percentage represents the proportion of records included in the quarter 7 report after the data cleaning process, this is listed below as total records and stroke records. Total Percentage Percentage Stroke Stroke Total number of number of of stroke of all records records records records submitted records records submitted submitted included SHA Trust Hospital via the webtool in included submitted included in via the after Quarter 7 after included in Quarter 7 webtool in cleaning (Stroke/TIA/Other) cleaning Quarter 7 Report Quarter 7 Quarter 7 Quarter 7 Report East Chesterfield -

Full Business Case for the Merger of Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust and the Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust

Full Business Case for the merger of Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust and The Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust 22 March 2018 Final Draft Version – Prepared for Trust Board 29 March 2018 Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust and The Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust Merger Full Business Case 2 | P a g e Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust and The Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust Merger Full Business Case Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Background ............................................................................................................................. 9 1.3 The case for change ................................................................................................................ 9 1.4 Benefits of merging ............................................................................................................... 10 1.5 The ESNEFT mission, vision and philosophy ........................................................................ -

Pacman TEMPLATE

Updated May 2020 National Cardiac Arrest Audit Participating Hospitals The total number of hospitals signed up to participate in NCAA is 194. England Birmingham and Black Country Participant Alexandra Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Birmingham Heartlands Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust City Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Good Hope Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Hereford County Hospital Wye Valley NHS Trust Manor Hospital Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust New Cross Hospital The Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust Russells Hall Hospital The Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Trust Sandwell General Hospital Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Solihull Hospital University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Worcestershire Royal Hospital Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Central England Participant George Eliot Hospital George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust Glenfield Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Kettering General Hospital Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Leicester General Hospital University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Leicester Royal Infirmary University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Northampton General Hospital Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust Hospital of St Cross, Rugby University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust University Hospital Coventry University Hospitals Coventry -

RCPCH Membership Data East of England Area

700 600 Consultant 500 ST1 - 4 + Fys 400 ST5 - 8 + staff grade 300 Retired 200 Medical student 100 Academic 0 GP Age Position Leicester Royal Infirmary Queen's Medical Centre Addenbrookes Hospital Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital Lister Hospital Luton and Dunstable Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Queen's Hospital Nottingham City Hospital Peterborough City Hospital Watford General Hospital Northampton General Hospital Royal Derby Hospital Location with most members Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust All locations Princess Alexandra Hospital Lincoln County Hospital Luton & Dunstable Hospital Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NHS Trust Southend University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Broomfield Hospital Colchester General Hospital University Hospitals Of Leicester NHS Trust The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Derbyshire Children's Hospital West Suffolk Hospital NHS Trust Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust Pilgrim Hospital University of Cambridge Kings Mill Hospital University of Nottingham Hinchingbrooke Hospital Kettering General Hospital Southend Hospital University of Leicester Barking, Havering and Redbridge Hospitals NHS Trust Glenfield Hospital Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Ipswich Hospital Queen Elizabeth II Hospital West Suffolk Hospital Chesterfield Royal Hospital Queen's Hospital Basildon Hospital Bedford Hospital Ipswich Hospital NHS -

Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust (CHUFT)

Colchester Hospital University NHS foundation Trust (CHUFT) www.colchesterhospital.nhs.uk College Tutor: Dr Jonathan Campbell - [email protected] Rota Co-ordinators: T1 (ST1-3/ANNP) – Dr Jo Anderson [email protected], T2 (St4+/Associate specialist) - Dr Jonathan Campbell [email protected] Clinical Lead: Dr Andrea Turner Matron: Gail Jenkins Children’s Services at Colchester hospital, is a welcoming, enjoyable place to work. We are ranked first overall in the East of England in the 2017 GMC survey for paediatric training (positive outliers for several aspects of training) and rated ‘good’ by the CQC. We are linked in L1 training in rotations with a variety of trust, primarily Cambridge, Norwich and Ipswich. Many of our previous trainees have returned to work in the department again, either at later stages in their training, or as consultants. We have a pleasant working environment, an active teaching and simulation programme (and an active series of social activities!) The Team: Consultants and their sub-specialities: • Dr Joakim Anderson Neonatology / respiratory • Dr Nicola Cackett Diabetes • Dr Jonathan Campbell HDU / neonatology / renal (College Tutor) • Dr Elena Cattaneo Oncology • Dr Kalyaan Devarajan Gastroenterology (Deputy Lead) • Dr Angeliki Menounou Epilepsy • Dr Sadia Rao Neonatology • Dr Bhupinder Sihra Respiratory, allergy & immunology • Dr Rajeev Shinkar Diabetes, allergy • Dr Angela Tillett Oncology, cardiology (Trust Medical Director) • Dr Andrea Turner Nephrology (Clinical Lead) In addition there are: Three Associate Specialists Six ST4-8 trainees Six ST1-3 paediatric trainees Five GP ST trainees Two ANNP’s Two FY2 trainees Two FY1 trainees We meet the RCPCH facing the future standards, with consultant presence in the department between 0900-2200, 7 days a week. -

Mr D Coelho V Colchester Hospital University NHS

Case Number: 3200914/2017 RM EMPLOYMENT TRIBUNALS Claimant: Mr D Coelho Respondent: Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust Heard at: East London Hearing Centre On: 18 & 19 January 2018 6 February 2018 (by telephone) Before: Employment Judge Russell Representation: Claimant: Ms S Keogh (Counsel) Respondent: Mr B Gardiner (Counsel) RESERVED JUDGMENT 1. The Claimant was entitled to treat himself as dismissed by reason of the Respondent’s conduct. His dismissal was unfair. 2. The claim for a redundancy payment fails and is dismissed. REASONS 1 By a claim form presented on 4 August 2017, the Claimant brings complaints of unfair dismissal and failure to make a redundancy payment arising out of the termination of his employment with the Respondent. The Respondent resisted all claims. 2 The parties produced separate list of issues which broadly overlapped but addressed the claims in a different order. The Claimant dealt first with the statutory redundancy payment and then with unfair dismissal; the Respondent addressed them in the reverse order. I consider that it is necessary first to decide whether the Claimant was dismissed by the Respondent before considering the implications of that dismissal. The issues are therefore: 2.1 was the Claimant dismissed by the Respondent on 27 May 2017, either by the employer within s.95(1)(a) ERA 1996 or s.136(1)(a) ERA 1996 or by the employee within s.96(1)(c) or s.136(1)(c)? 1 Case Number: 3200914/2017 2.1.1 For dismissal by the employer, did the Respondent unilaterally impose different terms -

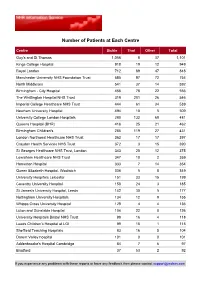

Number of Patients at Each Centre

Number of Patients at Each Centre Centre Sickle Thal Other Total Guy's and St Thomas 1,056 8 37 1,101 Kings College Hospital 918 19 12 949 Royal London 712 89 47 848 Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust 585 97 72 754 North Middlesex 541 37 14 592 Birmingham - City Hospital 456 78 22 556 The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust 319 201 26 546 Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust 444 61 34 539 Newham University Hospital 494 10 5 509 University College London Hospitals 280 132 69 481 Queens Hospital (BHR) 416 25 21 462 Birmingham Children's 285 119 27 431 London Northwest Healthcare NHS Trust 363 17 17 397 Croydon Health Services NHS Trust 372 3 15 390 St Georges Healthcare NHS Trust, London 343 20 12 375 Lewisham Healthcare NHS Trust 347 10 2 359 Homerton Hospital 333 7 14 354 Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woolwich 336 5 8 349 University Hospitals Leicester 151 33 15 199 Coventry University Hospital 158 24 3 185 St James's University Hospital, Leeds 142 30 5 177 Nottingham University Hospitals 134 12 9 155 Whipps Cross University Hospital 128 4 4 136 Luton and Dunstable Hospital 104 22 0 126 University Hospitals Bristol NHS Trust 98 16 4 118 Leeds Children's Hospital at LGI 99 15 1 115 Sheffield Teaching Hospitals 83 16 5 104 Darent Valley hospital 101 0 0 101 Addenbrooke's Hospital Cambridge 84 7 6 97 Bradford 37 53 2 92 If you experience any problems with these reports or have any feedback then please contact [email protected] Centre Sickle Thal Other Total Oxford Children's Hospital 78 11 2 91 Northampton General Hospital 82 3 2 87 New -

Download Colchester Hospital Case Study

NHS Hospital case study KiWi Power leads the way with healthcare providers Key project benefits Partnering with Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust for demand response Annual Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust has two main revenues: £ 100,000+ sites, Colchester General Hospital and Essex County Hospital. The The Trust employs more than 3,400 people providing healthcare Zero services to around 370,000 people from Colchester and the setup costs surrounding area of north east Essex. Colchester General Hospital opened in 1984 and is one of Essex’s largest facilities. Their care covers 596 inpatient beds, 44 maternity beds and 12 critical care No disruption to operation beds (excluding A&E). of sites Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust successfully oversaw the investment and overhaul of the Reduction of mechanical and electrical infrastructure of the site in 2012. CO2 emissions A key objective of this project was to upgrade and improve the resilience and testing regime of its backup generation. Access to real When KiWi Power approached the Trust, their energy and senior team recognised time energy immediately the vast potential of demand response for their site in fulfilling three management key objectives: dashboard with • Enhance the Trust’s resilience testing regime enhanced • Generate a new and recurring revenue stream monitoring • Improve triad management and increase utility bill savings. features KiWi Power Ltd, 45 Broadwick Street, London W1F 9QW | +44 (0)207 183 1030 | [email protected] | www.kiwipowered.com How KiWi Power delivered for Colchester Hospital: Assessment and design • KiWi Power installed proprietary demand response, one minute real time metering hardware which integrates with • KiWi Power’s engineers visited the sites to meet onsite voltage metering systems. -

Insights Into Hospital Discharge

Essex Insights into Hospital Discharge A study of patient, carer and staff experience at Broomfield Hospital Dr Oonagh Corrigan Dr Alexandros Georgiadis Abbi Davies Dr Pauline Lane Emma Milne Dr Ewen Speed Duncan Wood Acknowledgements We are, first and foremost, indebted to the patients and carers who shared their experiences of hospital discharge at Broomfield Hospital. Their stories offer rare and invaluable insight into where improvements can be made and we hope other patients and carers will benefit from them. We are also very grateful to the ward and discharge team staff for sharing their insight into the discharge process honestly and articulately in interviews, and to the whole discharge team for letting themselves be observed for the purposes of uncovering good discharge practice and areas for improvement. Our thanks go to hospital Medical Director, Dr Ronan Fenton, and Acting Chief Nurse, Lyn Hinton, for helping to facilitate access to the hospital and receiving the findings proactively and with enthusiasm. Also we would like to express our thanks to Professor Justin Waring and Dr. Simon Bishop from Nottingham University Business School for their advice during the design and planning stages of the study. We would also like to acknowledge other Healthwatch Essex staff; Dr Ofra Koffman who put together the successful ethics application, Sarah Haines who uncovered local and national information providing important context for the study, and Dr Tom Nutt, Chief Executive Officer of Healthwatch Essex, for his guidance and support. Finally, this ambitious piece of research would not have been possible without the dedication and enthusiasm of Healthwatch Essex Ambassadors, Janet Tarbun and Lauraine George, who offered their time for free to administer surveys in the discharge lounge. -

Handbook for Nurses & Midwives

Serving the people of north east Essex HANDBOOK FOR NURSES & MIDWIVES Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust Page 1 of 15 Nursing & Quality Revised July 2010 V9 CONTENTS Page No. Subject 3 Introduction 3 Nursing & Patient Experience Department 4 NHS Healthcare Provision in North East Essex Bed Management / Policies & Procedures/ Clinical Nurse 6 Specialists/ Hospital Specialist Palliative Care Team/ Outreach Team Pharmaceutical Services. 8 Position Statement on Clinical Supervision 9 Data Protection Act 1984 10 General Information 11 Health & Safety at Work Health and Wellbeing Service 12 North Essex Library & Information Services 15 Request form for Clinical Supervision Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust Page 2 of 15 Nursing & Quality Revised July 2010 V9 Introduction Welcome to the Trust, which serves the population of North East Essex. In partnership with the local Primary Care Trust (PCT) called NHS North East Essex The Trust is committed to on-going professional development of all staff using in-house training facilities and our local education providers (Anglia Ruskin University, Essex University and Colchester Institute). Colchester is a rapidly expanding regional centre of commerce and technology, with a population, which will grow at twice the national average over the next 10 years. It is 12 miles from the Essex coast and close to ‘Constable Country’. It is easily accessible from London by road or rail (55 minutes from Liverpool Street) and is close to Stansted Airport and the port of Harwich. Nurses -

NACT UK Norfolk House East, 499 Silbury Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes MK9 2AH

NACT UK Norfolk House East, 499 Silbury Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes MK9 2AH Tel: 01908 488033 [email protected] www.nact.org.uk Chair Hon Secretary Hon Treasurer Dr A Cooper Dr R Aspinall Dr A Malin Medical Edn Centre Education Centre Postgraduate Centre Rotherham General University Hospital Bristol Royal United Hospital Hospital NHS Trust NHS Foundation Trust Combe Park Moorgate Road Upper Maudlin Street Bath BA1 3NG Rotherham S60 2UD Bristol BS2 8AE 01225 824891 01709 307868 0117 3420 053 Vice Chairman – Dr S Remington 0161 625 7639 Honorary Assistant Secretary – Dr D Mulherin 01543 576716 Editor “Clinical Tutor” – Dr D McKeon 01248 384621 The National Association of Clinical Tutors (NACT) was originally founded in 1969 to further the interests of what were then called District Clinical Tutors nationally and to help and support them in their work. Our membership has grown since then to encompass the variety of leading educators involved at the local level in the management and delivery of postgraduate medical education across the UK. Through our courses, workshops and conferences, we provide opportunities for our members and others to improve their skills and knowledge in the field of PGME. NACT UK liaises on behalf of its members with many national bodies involved in Medical Education. We communicate our knowledge of these to our membership through a long established information cascade system. To emphasise its role across the UK, on 10th May 2007 the members voted for the organisation to be known as NACT UK. Our association membership is primarily made up of: Clinical Tutors/ Directors of Medical Education/Faculty Leads (Wales), Foundation Programme Directors, SAS Tutors, Training Programme Directors, Associate Deans, College Tutors and MEMs (who are Members of NAMEM) although we are happy to consider anyone involved in PGME who share our aims. -

Review of Cancer Services at Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust

Report into the Immediate Review of Cancer Services at Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust Report into the Immediate Review of Cancer Services at Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust First published: 19 December 2013 Publications Gateway Reference No. 00958 2 1 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 11 1.1 Governance of Cancer services .................................................................. 11 1.1.1 Clinical pathways .................................................................................. 11 1.1.2 Multi-Disciplinary Teams ....................................................................... 12 1.1.3 Handover between cancer teams or hospitals ...................................... 12 1.1.4 Corporate governance .......................................................................... 12 1.2 Information and record systems .................................................................. 13 1.3 Staffing levels, workload, training and accommodation ............................... 14 1.4 Specialist Cancer services arrangements ................................................... 14 1.5 The structure of Cancer services in England............................................... 15 1.5.1 Peer review levels of assurance ........................................................... 16 1.6