A Critical Study on Aam Aadmi Party Working in Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parkash Singh Badal by : INVC Team Published on : 30 Aug, 2015 05:00 PM IST

Talwandi's contribution for panth, punjab & punjabiat enormous : Parkash Singh Badal By : INVC Team Published On : 30 Aug, 2015 05:00 PM IST INVC NEWS Ludhiana, The first 'Barsi Samagam' of Senior Akali leader and former president of Shiromani Gurudwara Parbandhak Committee was organised at Gurudwara Tahliana Sahib, here today which was attended by Punjab CM Mr Parkash Singh Badal and a large number of personalities from different walks of life. While speaking on the occasion, CM Mr Parkash Singh Badal praised Jathedar Jagdev Singh Talwandi for his enormous contribution towards Panth, Punjab and Punjabiat. Mr. Badal said that the life and struggle of Jathedar Talwandi would ever act as a lighthouse for the coming generations to serve the state and the Panth with utmost zeal, sincerity and commitment. He said that probably Jathedar Talwandi was the only political leader who had served the state socially, politically and even religiously by being the President of Shiromani Akali Dal and Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee besides being a Member of Parliament and MLA of the state assembly. Badal said that with the death of Jathedar Talwandi a void has been created which would be difficult to fill in the near future. Recalling the outstanding services rendered by Jathedar Talwandi during the landmark agitations like Punjabi Suba, Emergency, Dharam Yudh and others, the Chief Minister said that the Jathedar Talwandi was a fearless leader who never comprised with the interests of the state and Panth. Describing Jathedar Talwandi as a decisive leader, Mr. Badal said that he never hesitated to take any bold decision if it was in the interest of Punjab and its people. -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

Delhi Prashant Kishor

$- > / !2?#@% #@%@ VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( 2.-3+*45 / 181/8; :/)5! 74834 9 /2 / , 1/:11 6 C.1, 6: 11 ./1 4: ., 6 /:6.6:1:< <:, <: /.< ,: 4:< 6., :< <:D 1 :< <1 4 1.1 <:. <:6:B 7: :: , /!.)+ %- )*= A:1!:%%2 #6 $,#$ 7*787+9 +7) *+R - .R && ( pro-poor people governance,” said the Karnataka ) %(* CM-elect soon after he was elected to the post. + The outgoing Chief Minister, Yediyurappa, said, “We have unanimously elected Bommai as CM....we are asavaraj S Bommai, 61, the very happy.” BState Home Minister, a The MLAs’ meeting at “Lingayat” by caste and a close Bengaluru’s Hotel Capitol that !! confidant of BS Yediyurappa elected Bommai was attended was on Tuesday declared the by the Central observers — new Chief Minister of Union Ministers Dharmendra Karnataka after BJP legislature Pradhan, G Kishan Reddy and est Bengal Chief Minister party met at the State capital. general secretary and State-in- WMamata Banerjee on a Bommai is expected to charge Arun Singh. Pradhan high-profile visit to the nation- take oath of Chief Ministership announced the name of al Capital met Prime Minister on Wednesday. Bommai as a successor to Narendra Modi at his resi- The name of Bommai, the Yediyurappa amid loud cheers dence on Tuesday ahead of a son of former State Chief and clapping. series of meetings with top Minister SR Bommai (a Janata By picking-up Bommai, a Opposition leaders to prepare parivar leader) who had joined Sadara “Lingayat”, the BJP the strategy for a unified chal- the BJP in 2008, was proposed seemed to have satisfied the lenge to the BJP in the 2024 by Yediyurappa, the “Lingayat” caste dynamics of Karnataka, Lok Sabha polls. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

In India, Election Season Is Never Over Richard Rossow

July 28, 2014 In India, Election Season Is Never Over Richard Rossow The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) historic victory in the spring 2014 Lok Sabha1 election was a tremendous accomplishment—yet it still leaves the party with impartial control, at best. Weakness in the Rajya Sabha,2 where the BJP only holds 43 out of 243 seats, may limit the party’s ability to enact legislative reforms. And the fact that the BJP only controls 5 of India’s 29 states will also blunt the impact of any policy measures adopted at the center. In order to enact a true economic transformation, the BJP will either need the support of a wide range of unaligned parties—which would be a historical abnormality—or to consolidate its power at the state level by winning upcoming state elections. With the BJP’s powerful show of force across India in the Lok Sabha election, winning state elections appears to be a viable path. Between now and the end of 2016, 10 states will hold elections. The BJP is not the incumbent in any of these states. However, in the recent Lok Sabha elections, the BJP and National Democratic Alliance (NDA) allies won at least 50 percent of the seats in six of these states. So the BJP appears poised to do well in these state elections if they can maintain momentum. But “momentum” will mean different things to different people. States with Elections in the Next Three Years State Party in Power Expiration BJP Seats in 2014 Lok Sabha Haryana Congress 10/27/14 7 of 10 Maharashtra Congress 12/7/14 23 of 48 Jharkhand JMM- Congress 1/3/15 12 of 14 J&K J&K Nat’l Conf. -

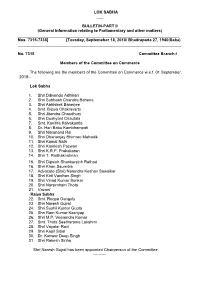

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Lok Sabha Secretariat

LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Details of expenditure incurred on HS/HDS/LOP/MP(s)* During the Period From 01/04/2016 To 30/06/2016 Office Salary for Arrears(if SL ICNO Name of MP/ Salary Constituency Travelling/ Expense/ Available) State Allowance Secretarial daily Sumptury Assistant Allowence Allowance 160001 Shri Godam Nagesh 1 100000 90000 30000 60000 400213 0 Andhra Pradesh 160002 Shri Balka Suman 2 100000 90000 30000 60000 1074137 0 Andhra Pradesh 160003 Shri Vinod kumar 3 100000 90000 30000 60000 432644 Boianapalli 0 Andhra Pradesh 160004 Smt. Kalvakuntla Kavitha 4 100000 90000 30000 60000 943342 0 Andhra Pradesh 160005 Shri Bheemrao 5 100000 90000 30000 60000 296037 Baswanthrao Patil 0 Andhra Pradesh 160006 Shri Kotha Prabhakar 6 100000 90000 30000 60000 441677 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160007 Ch.Malla Reddy 7 100000 90000 30000 60000 114435 0 Andhra Pradesh 160008 Shri Bandaru Dattatreya 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 Andhra Pradesh 160009 Shri Owaisi Asaduddin 9 100000 90000 30000 60000 359690 0 Andhra Pradesh 160010 Shri Konda Vishweshar 10 100000 90000 30000 60000 536228 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160011 Shri A.P.Jithender Reddy 11 100000 90000 30000 60000 567967 0 Andhra Pradesh 160012 Shri Yellaiah Nandi 12 100000 90000 30000 60000 312249 0 Andhra Pradesh 160013 Shri Gutha Sukender 13 100000 90000 30000 60000 579428 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh 160014 Dr.Boora Narsaiah Goud 14 100000 90000 30000 60000 195915 0 Andhra Pradesh 160015 Shri Dayakar Pasunoori 15 100000 90000 30000 60000 942860 0 Andhra Pradesh 160016 Prof. Azmeera Seetaram 16 100000 90000 30000 60000 762550 Naik 0 Andhra Pradesh 160017 ShriPonguleti Srinivasa 17 100000 90000 30000 60000 400099 Reddy 0 Andhra Pradesh LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Details of expenditure incurred on HS/HDS/LOP/MP(s)* During the Period From 01/04/2016 To 30/06/2016 Office Salary for Arrears(if SL ICNO Name of MP/ Salary Constituency Travelling/ Expense/ Available) State Allowance Secretarial daily Sumptury Assistant Allowence Allowance 160018 Smt. -

The Study of Mr. Narendra Modi's General Election

Project Dissertation THE STUDY OF MR. NARENDRA MODI’S GENERAL ELECTION (2014) STRATEGY: POST NOMINATION TO PRIME MINISTERIAL JOURNEY ANALYSIS Submitted by: Dishant Gosain MBA/2K13/25 Under the guidance of Dr. Vikas Gupta Assistant Professor DSM DELHI SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT Delhi Technological University Bawana Road Delhi 110042 Jan -May 2015 vii 2015 One THE STUDY OF MR. NARENDRA MODI’S GENERAL ELECTION (2014) STRATEGY: POST NOMINATION TO PRIME MINISTERIAL JOURNEY ANALYSIS DISHANT GOSAIN ii 2K13/MBA/25 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation titled “THE STUDY OF MR. NARENDRA MODI’S GENERAL ELECTION (2014) STRATEGY: POST NOMINATION TO PRIME MINISTERIAL JOURNEY ANALYSIS”, is a bonafide work carried out by Dishant Gosain, student of MBA 2013-15 and submitted to Delhi School of Management, Delhi Technological University, Bawana Road, Delhi-42 in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of Masters of Business Administration. Signature of Guide Signature of Head (DSM) Seal of Head Place: New Delhi Date: 01/05/2015 iii DECLARATION I, Dishant Gosain, student of MBA 2013-15 of Delhi School of Management, Delhi Technological University, Bawana Road, Delhi-42 declare that the dissertation on “THE STUDY OF MR. NARENDRA MODI’S GENERAL ELECTION (2014) STRATEGY: POST NOMINATION TO PRIME MINISTERIAL JOURNEY ANALYSIS” submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of Masters of Business Administration is the original work conducted by me. The information and data given in the report is authentic to the best of my knowledge. The report is not being submitted to any other University for award of any other Degree, Diploma and Fellowship. -

LIST of RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (As on 11.01.2017)

LIST OF RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) Sl. Name of the Name of President/ Address No. Party General secretary 1. Bahujan Samaj Ms. Mayawati, Ms. Mayawati, Party President President Bahujan Samaj Party 4, Gurudwara Rakabganj Road, New Delhi –110001. 2. Bharatiya Janata Shri Amit Anilchandra Shri Amit Anilchandra Shah, Party Shah, President President Bharatiya Janata Party 11, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 3. Communist Party Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, of India General Secretary General Secretary, Communist Party of India Ajoy Bhawan, Kotla Marg, New Delhi – 110002. 4. Communist Party Shri Sitaram Yechury, Shri Sitaram Yechury, of General Secretary General Secretary India (Marxist) Communist Party of India (Marxist) ,A.K.Gopalan Bhawan,27-29, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market), New Delhi - 110001 5. Indian National Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Congress President President Indian National Congress 24,Akbar Road, New Delhi – 110011 6. Nationalist Shri Sharad Pawar, Shri Sharad Pawar, Congress Party President President Nationalist Congress Party 10, Bishambhar Das Marg, New Delhi-110001. 7. All India Ms. Mamta Banerjee, All India Trinamool Congress, Trinamool Chairperson 30-B, Harish Chatterjee Street, Congress Kolkata-700026 (West Bengal). LIST OF STATE PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) S. No. Name of the Name of President/ Address party General Secretary 1. All India Anna The General Secretary- No. 41, Kothanda Raman Dravida Munnetra in-charge Street, Chennai-600021, Kazhagam (Tamil Nadu). (Puratchi Thalaivi Amma), 2. All India Anna The General Secretary- No.5, Fourth Street, Dravida Munnetra in-charge Venkatesware Nagar, Kazhagam (Amma), Karpagam Gardens, Adayar, Chennai-600020, (Tamil Nadu). -

Membersofparliament(Xvehloksabha)Nominatedaschairman/Co-Chairmantothe Committtee (DISHA) District Development Coordination & Monitoring

MembersofParliament(XVEhLokSabha)NominatedasChairman/Co-Chairmantothe Committtee (DISHA) District Development Coordination & Monitoring ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS Member of Parliament Members of Parliament (XVlth Lok Sabha) Nominated as Chairman/Co- chairman to the District Development coordination & Monitoring committtee ANDHRA PRADESH District Member of Parliament Chairman/Co-Chairman Chairman Anantapur Shri Kristappa Nimmala Shri J-C. Divaka r Reddy Co-Chairman chairman Chittoor Dr. Naramalli SivaPrasad Shri Midhun Reddy Co-chairman Dr. Vara Prasadarao Velaga Palli Co-Chairman East Godavari Shri Murali Mohan Maganti Chdimon Co-Choirmon Sh ri Narasimham Thota Dr. Ravindra Babu Pandula Co-choirmon Smt. Geetha KothaPa lli Co-choirmon chairman Guntur Shri Rayapati Samb!9!Yq leo Co-Chairman Shri Jayadev Galla Co-Chairman Shri Sriram MalYadri chairman Kadapa Shri Y. S. Avinash ReddY chri Mi.lhunn Reddv Co-Chairman Rao Chairman Krishna Shri Konakalla Narayana Co-Chairman Shri Srinivas Kesineni qhri Vankateswa ra Rao Masantti Co-Chairman Chairman Kurnool chrisPY-Reddev cmt Rpnllka Blltta Co-Chairman ReddY Chairman Nellore shri MekaDati Raiamohan nr \/era Prasadarao Velaea Palli Co-Chairman Subbareddy chairman Prakasam Shri Yerram Venkata cl-.,i C.iram l\rrl\/arlri Co-Chairman Co-Chairman Shri Mekpati Raiamohan ReddY Chairman Srikakulam Shri Ashok GajaPati Raju Pusapati Shri Kiniarapu Ram Mohan Naidu Co-Chairman Smt. Geetha KothaPalli Co-Chairperson Chairperson Vishakhapatnam Smt. Geetha KothaPalli Shri Muthamsetti Srinivasa Rao (Avnth Co-Chairman -

The BJP and State Politics in India: a Crashing Wave? Analyzing the BJP Performance in Five State Elections

AAssiiee..VViissiioonnss 8800 ______________________________________________________________________ The BJP and State Politics in India: A Crashing Wave? Analyzing the BJP Performance in Five State Elections _________________________________________________________________ Gilles VERNIERS December 2015 . Center for Asian Studies The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36537-498-0 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2015 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27, RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THÉRÈSE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 – FRANCE 1000 – BRUXELLES – BELGIQUE Tel: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tel: +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.ifri.org Ifri Center for Asian Studies Asia is at the core of major global economic, political and security challenges. The Centre for Asian Studies provides documented expertise and a platform of discussion on Asian issues through the publication of research papers, partnerships with international think- tanks and the organization of seminars and conferences.