A Relational Approach to Law Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exchange Student Honored

Entered as Second Class Matter Vol. 1, No. 26 Post Office Rahwav New JerSftv Clark, N. J.( Thursday, February 10, 1966 Price 1C cents Der copy T h e Q u i l l ... Clark Adopts School Budget; We’re pleased with the decision of the voters in Clark who passed the school budget last Tuesday. Re-elects Three Members We’re delighted that the school board officials pre sented a reasonable and acceptable budget for our people to approve. And we are, to a certain degree, To Local Board Of Education proud of the small part we played in seeing that the CLARK - Breaking what budget was accepted. Morrell Serving seemed to have become a habit Although there is no question that the Board was Elks Induct of rejecting school budgets, Exchange Clark residents voted Tuesday given a well-deserved vote of confidence, we do In Viet Nam to accept the proposed 1966-67 not feel that it was in any way given the right to re New Members With a total voter turnout of 1,652 residents passed the bud lax its vigilance and determination to cut every CLARK - Pvt. David E. Mor Student CLARK - Lodge B.O.P, Elks get in First Ward but lost at rell, son of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest unnecessary dollar out of the spending which will initiated the following members least one district in each of Morrell of 17 James Avenue, on February 3 at the American the other three. ensue this year. There is nothing that requires the is serving at Phough Vinh, Legion: Re-elected to the Board of Honored Viet Nam. -

Briefing Papers

The original documents are located in Box C45, folder “Presidential Handwriting, 7/29/1976” of the Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box C45 of The Presidential Handwriting File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library '.rHE PRESIDENT HAS SEEN ••-,.,.... THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEETING WITH PENNSYLVANIA DELEGATION Thursday, July 29, 1976 5:30 PM (30 minutes} The East Room ~f\ From: Jim Field :\ ./ I. PURPOSE To meet informally with the Pennsylvania delegates and the State Congressional delegation. II. BACKGROUND, PARTICIPANTS AND PRESS PLAN A. Background: At the request of Rog Morton and Jim Baker you have agreed to host a reception for the Pennsylvania delegation. B. Participants: See attached notebook. C. Press Plan: White House Photo Only. Staff President Ford Committee Staff Dick Cheney Rog Morton Jim Field Jim Baker Dick Mastrangelo Charles Greenleaf • MEMORANDUM FOR: H. James Field, Jr. FROM: Dick Mastrangelo SUBJECT: Pennsylvania Delegation DATE: July 28, 1976 Since Reagan's suprise announcement that he has asked Senator Schweiker to run for Vice President should the convention ever nominate them as a t•am we have been reviewing the entire Pennsylvania situation in order to give the President the most complete and up-to-datebriefing possible for his meeting with the Delegation on Thursday, July 29. -

In a Lonely Place Arlen Specter Is the Same. It's the GOP That's Changed

WEEK OF NOVEMBER 22, 2004 In A Lonely Place Arlen Specter is the same. ROBERTO WESTBROOK ROBERTO It’s the GOP that’s changed. BY T.R. GOLDMAN staff member was now 14 months away from being the longest serving senator in the history of Pennsylvania—after fellow The harsh glare of the single television spotlight made Arlen Republican Boise Penrose, who died in office on Dec. 31, 1921. Specter’s face shine unnaturally, and his smile was tight and He had survived a grueling primary against Rep. Patrick prearranged. Toomey (R-Pa.), and an unexpectedly tough general election The disembodied voice of CNBC’s Gloria Borger was work- against Rep. Joseph Hoeffel (D-Pa.). ing its way into Specter’s ear. Behind him, the rotunda of the But when Specter takes over the Senate Judiciary Committee Senate’s Russell Building glowed in the sunset. in January, as he now appears certain to do, he will be noted The conversation had turned to Richard Viguerie, the arch- more for surviving an infelicitous remark at a euphoric Nov. conservative direct mail guru, and one of those most promi- 3 press conference—that it was “unlikely” that the committee nently opposing the Pennsylvania Republican’s ascension to the would confirm any judicial nominee who would overturn Roe chairmanship of the Senate Judiciary Committee. v. Wade—than for possessing what his supporters say is a long “I’m not about to make any deals with Richard Viguerie,” and distinguished career as one of the Senate’s few remaining said Specter, his eyes blinking with intensity. -

Consultation and Coordination

Chapter 5 Frank Miles/USFWS Frank Great blue heron feeding on common carp at the refuge Consultation and Coordination ■ 5.1 Introduction ■ 5.2 Planning to Protect Land and Resources ■ 5.3 Partners Involved in Refuge Planning ■ 5.4 Contact Information ■ 5.5 Planning Team ■ 5.6 Other Service Program Involvement ■ 5.7 Other Involvement 5.1 Introduction 5.1 Introduction This chapter describes how we engaged others in developing this draft CCP/ EA. In chronological order, it details our efforts to encourage the involvement of the public and conservation partners: other Federal and State agencies, Tribes, county officials, civic groups, nongovernmental conservation and education organizations, and user groups. It also identifies who contributed in writing the plan or significantly contributed to its contents. It does not detail the dozens of informal discussions the refuge manager and his staff have had over the last two years where the CCP was a topic of conversation. Those involved a wide range of audiences, including local community leaders and other residents, refuge neighbors, refuge visitors, and other interested individuals. During those discussions, the refuge manager and his staff often would provide an update on our progress and encourage comments and other participation. A 30-day period for public review follows our release of this draft CCP/EA. We encourage you to respond with your ideas about the plan. During that period, we will host open-house public meetings at locations near the refuge to gather opinions and answer questions about our proposals. We will weigh public responses carefully before we finalize the CCP. -

The New Economy Proceedings

98th Congress JOINT COMMITTEE PRINT S. PRT. 2d Session Ij 98-232 THE NEW ECONOMY PROCEEDINGS OF A CONGRESSIONAL ECONOMIC CONFERENCE ON WEDNESDAY, JUNE 6, 1984 COSPONSORED BY THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES SUBCOMMITTEE ON GENERAL OVERSIGHT AND THE ECONOMY OF THE COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE CONGRESSIONAL CLEARINGHOUSE ON THE FUTURE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 37-865 0 WASHINGTON: 1984 JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE [Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Congress] SENATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ROGER W. JEPSEN, Iowa, Chairman LEE H. HAMILTON, Indiana, WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware Vice Chairman JAMES ABDNOR, South Dakota GILLIS W. LONG, Louisiana STEVEN D. SYMMS, Idaho PARREN J. MITCHELL, Maryland MACK MATTINGLY, Georgia AUGUSTUS F. HAWKINS, California ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York DAVID R. OBEY, Wisconsin LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts MARJORIE S. HOLT, Maryland PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine DAN C. ROBERTS, Executive Director JAMES K. GALBRAITH, Deputy Director COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS PARREN J. MITCHELL, Maryland, Chairman NEAL SMITH, Iowa JOSEPH M. McDADE, Pennsylvania JOSEPH P. ADDABBO, New York SILVIO 0. CONTE, Massachusetts HENRY B. GONZALEZ, Texas WM. S. BROOMFIELD, Michigan JOHN J. LAFALCE, New York LYLE WILLIAMS, Ohio BERKLEY BEDELL, Iowa JOHN HILER, Indiana HENRY J. NOWAK, New York VIN WEBER, Minnesota THOMAS A. LUKEN, Ohio HAL DAUB, Nebraska ANDY IRELAND, Florida CHRISTOPHER H. -

History Making

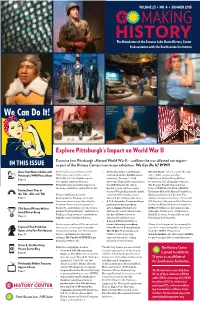

VOLUME 23 • NO. 4 • SUMMER 2015 MAKING HISTORY The Newsletter of the Senator John Heinz History Center In Association with the Smithsonian Institution Explore Pittsburgh’s Impact on World War II Examine how Pittsburgh affected World War II – and how the war affected our region – IN THIS ISSUE as part of the History Center’s new major exhibition, We Can Do It! WWII. Share Your History Online with As the nation commemorates the • Several artifacts and images We Can Do It! – which is open through Pittsburgh’s WWII Photo Album 75th anniversary of the start of on loan from the Smithsonian, Jan. 3, 2016 – is sponsored by World War II, this 10,000-square- including “Gramps,” a 1940 MSA Safety, Richard King Mellon Page 2 foot exhibit explores Western prototype Bantam Reconnaissance Foundation, The Heinz Endowments, Pennsylvania’s incredible impact on Car (BRC) that is the oldest The Bognar Family, Bob and Joan the home, industrial, and battle fronts. known jeep in existence and a Peirce, UPMC Health Plan, ABARTA, Coming Soon! Toys of Curtiss-Wright Airplane Propeller, Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation, the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s Visitors will learn about the courtesy of the Smithsonian’s Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney, P.C., Page 3 development of the jeep, a uniquely National Air and Space Museum; Jendoco Construction Corp., Tricia and American invention produced by the • A U.S. Army Air Corps uniform Bill Kassling, Miryam and Bob Knutson, American Bantam Car Company in jacket worn by legendary Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation, 23rd Annual History Makers Butler, Pa., and will uncover the stories actor Jimmy Stewart, the KDKA-TV, Millcraft Investments, Inc., behind “Rosie the Riveter” and the local Indiana, Pa. -

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Legislative

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL TUESDA yr APRIL 9 r 1991 SESSION OF 1991 175TH OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY No. 20 SENATE April 9, 1991 TUESDAY, April 9, 1991. HB 10- Committee on Military and Veterans Affairs. The Senate met at 11:00 a.m., Eastern Daylight Saving HB 77 - Committee on Judiciary. Time. HB 89 and 93 - Committee on Game and Fisheries. The PRESIDENT (Lieutenant Governor Mark S. Singel) HB 101- Committee on Transportation. in the Chair. RESOLUTION INTRODUCED AND REFERRED PRAYER The PRESIDENT laid before the Senate the following The Chaplain, Reverend ROBERT FRANCO, Pastor of Senate Resolution numbered, entitled and referred as follows, which the Church of Saint Cyril of Alexandria, Pittsburgh, offered was read by the Clerk: the following prayer: April 9, 1991 Almighty God, we remember the families of Senator Heinz DIRECTING THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT and Senator Tower as they mourn the tragic deaths of their COMMISSION TO UNDERTAKE A CODIDCATION loved ones. You know who we are. You care little for our OF THE STATUTES RELATING TO earthly show, our feeble ardors. What pleases You is how well REAL PROPERTY ASSESSMENTS we serve. Give us of Your strength to bear the burdens. Give Senators JUBELIRER, HOPPER, SHUMAKER, us of Your wisdom to solve the problems. Give us of Your MADIGAN, CORMAN, AFFLERBACH, REIBMAN, courage to forge new tasks. Give us curiosity to try new paths. SHAFFER, BRIGHTBILL, HART, PUNT and RHOADES Let us guide this Commonwealth along paths pleasing to You offered the following resolution (Senate Resolution No. 44), and beneficial to Your people. -

H. Doc. 108-222

NINETY-THIRD CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1973, TO JANUARY 3, 1975 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1973, to December 22, 1973 SECOND SESSION—January 21, 1974, 1 to December 20, 1974 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—SPIRO T. AGNEW, 2 of Maryland; GERALD R. FORD, 3 of Michigan; NELSON A. ROCKEFELLER, 4 of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JAMES O. EASTLAND, of Mississippi SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—FRANCIS R. VALEO, of the District of Columbia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM H. WANNALL, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—CARL ALBERT, 5 of Oklahoma CLERK OF THE HOUSE—W. PAT JENNINGS, 5 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—KENNETH R. HARDING, 5 of Virginia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM M. MILLER, 6 of Mississippi; JAMES T. MOLLOY, 7 of New York POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT V. ROTA, 5 of Pennsylvania ALABAMA Barry M. Goldwater, Scottsdale Harold T. Johnson, Roseville SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John E. Moss, Sacramento John J. Sparkman, Huntsville John J. Rhodes, Mesa Robert L. Leggett, Vallejo James B. Allen, Gadsden Morris K. Udall, Tucson Phillip Burton, San Francisco William S. Mailliard, 10 San Francisco REPRESENTATIVES Sam Steiger, Prescott John B. Conlan, Phoenix John Burton, 11 San Francisco Jack Edwards, Mobile Ronald V. Dellums, Berkeley William L. Dickinson, Montgomery ARKANSAS Fortney H. (Pete) Stark, Danville Bill Nichols, Sylacauga SENATORS Don Edwards, San Jose Tom Bevill, Jasper Charles S. Gubser, 12 Gilroy Robert E. Jones, Scottsboro John L. McClellan, Little Rock J. William Fulbright, 9 Fayetteville Leo J. Ryan, South San Francisco John Buchanan, Birmingham Burt L. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXVI October 2012 NO. 4 EDITORIAL Tamara Gaskell 329 INTRODUCTION Daniel P. Barr 331 REVIEW ESSAY:DID PENNSYLVANIA HAVE A MIDDLE GROUND? EXAMINING INDIAN-WHITE RELATIONS ON THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA FRONTIER Daniel P. Barr 337 THE CONOJOCULAR WAR:THE POLITICS OF COLONIAL COMPETITION, 1732–1737 Patrick Spero 365 “FAIR PLAY HAS ENTIRELY CEASED, AND LAW HAS TAKEN ITS PLACE”: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SQUATTER REPUBLIC IN THE WEST BRANCH VALLEY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, 1768–1800 Marcus Gallo 405 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS:A CUNNING MAN’S LEGACY:THE PAPERS OF SAMUEL WALLIS (1736–1798) David W. Maxey 435 HIDDEN GEMS THE MAP THAT REVEALS THE DECEPTION OF THE 1737 WALKING PURCHASE Steven C. Harper 457 CHARTING THE COLONIAL BACKCOUNTRY:JOSEPH SHIPPEN’S MAP OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER Katherine Faull 461 JOHN HARRIS,HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION, AND THE STANDING STONE MYSTERY REVEALED Linda A. Ries 466 REV.JOHN ELDER AND IDENTITY IN THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY Kevin Yeager 470 A FAILED PEACE:THE FRIENDLY ASSOCIATION AND THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY DURING THE SEVEN YEARS’WAR Michael Goode 472 LETTERS TO FARMERS IN PENNSYLVANIA:JOHN DICKINSON WRITES TO THE PAXTON BOYS Jane E. Calvert 475 THE KITTANNING DESTROYED MEDAL Brandon C. Downing 478 PENNSYLVANIA’S WARRANTEE TOWNSHIP MAPS Pat Speth Sherman 482 JOSEPH PRIESTLEY HOUSE Patricia Likos Ricci 485 EZECHIEL SANGMEISTER’S WAY OF LIFE IN GREATER PENNSYLVANIA Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe 488 JOHN MCMILLAN’S JOURNAL:PRESBYTERIAN SACRAMENTAL OCCASIONS AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING James L. Gorman 492 AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LINGUISTIC BORDERLAND Sean P. -

When You Read This, You'll Have an Advantage. You Will Know

1 Prelude March 2010 hen you read this, you’ll have an advantage. you will know who won. As i begin to write, however, i’m not even sure W who’s running. That the republican candidate for the United states senate from pennsylvania in 2010 will be forty-eight-year- old patrick Joseph Toomey, sr., of Zionsville in the lehigh valley is the only certainty. Well, that and the likelihood that this race will prove to be among the most compelling of a particularly tumultuous election year. Who wouldn’t want to write about it? Toomey’s opponent, to be determined in the may 18 Democratic primary, will be either the five-term incumbent, eighty-year-old Arlen specter of philadelphia, or fifty-eight-year-old former admiral and Congressman Joseph A. sestak, Jr., of secane, Delaware County, in the philadelphia suburbs. For Toomey, facing specter in the 2010 general election would represent a peculiar rematch of their very close primary contest in 2004. There is nothing new about trying to define each party’s ideologi- cal distinctions. Almost five decades ago Barry Goldwater pledged “a choice, not an echo.” some three decades before that, when the power of his improbable new Deal electoral coalition was at its height, Frank- lin roosevelt mused about party realignment, on the english style, with everyone on the right united under the republican banner, and all those on the left (a perpetual majority, he hoped) gathered under the great tent 2 / Chapter 1 of the Democrats. it never happened. But, in whatever form, the two-party system has survived, despite the occasional emergence of a George Wallace or ross perot. -

2016-2017 Annual Report Center for Victims Is the Most Comprehensive

2016-2017 Annual Report Center for Victims is the most comprehensive and inclusive provider of services, advocacy, and education for all victims of crime in Allegheny County, and in Pennsylvania. Center for Victims serves those affected by a myriad of crimes, all at different ages and ethnicities. Types of Crime 61,878 Hours of Service Percent of Clients, by age Female………………..3,239 Male…………………….586 Transgender………….6 Number of Clients by Crime: Domestic Violence………...3,831 Sexual Assault………………..1,798 Other Crimes………………….9,891 Total Agency Clients………..15,520 Expenses Management Fundraising and General 4% 11% Program Services 85% Revenue Management Fees Fundraising In-kind & Other Program 2% Contribution Services 3% 4% Donations 9% Grants 84% 2016-2017 Donors Individuals: Colleen Rumble Fran Trimpey Abby Madia Colleen Perry Gail Schenone Alaina Lazzari Cynthia Dague Gene Strassburger Alexander Cashman Cynthia Baldwin Heather Douglass Burtch Alice Pastirik Cynthia Bily Howard Morgan Alicia Carberry Cynthia Piccirilli Jack King Allen Menozzi Dan Cusick James Bayer Allison Barton Daniel Doyle James Bayer Amber Epps Danielle Davis James Bray Amy Apel David Spurgeon, Esq. James Kenney Amy Cortes David Mills James Rieland Anita Kulik David Atkins Janet Necessary Ashwin Somasundara David Cordier Jean O'Connell Jenkins Barb Firda David Dalcanton Jennifer Milanak Barbara Wright David Ventura Jessica Katchur Bonita Farinelli Deborah Comay Jim Vivirito Bradley Garrison Delores Perrotta Joel Pretz Brandon Franklin Denis Meinert John Graf Brenda Roberts -

Campaign Trips (3)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 32, folder “Campaign Trips (3)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 32 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library INFORMATION ABOUT OREGON Nickname The Beaver State Motto The Union Flower Oregon Grape Bird Western Meadowlark Tree Douglas Fir Song Oregon, My Oregon Stone Thunder egg Animal Beaver Fish Chinook Salmon SELECTED OFFICIALS Executive Officials: Elected by: Governor Robert Straub (D) 57.7% Lt. Governor Secretary of State Clay Myers (R) 61. 5 Attorney General Lee Johnson (R) 50.9 Republican State Senators 7 of 30 Republican State Representatives 22 of 60 Congressional Delegation: Senators Mark 0. Hatfield (R) Bob Packwood (R) Representatives 1. Les AuCoin (D) Cornvallis, Salem, Portland 2. Al Ullman (D) Salem 3. Robert Blackford Duncan (D) Portland 4. James Howard Weav.er {D) Eugene, Springfield, Med ford Presidential Appointees in U.S.