The Family Justice Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"No-Fault Divorce"

BRIEFING PAPER Number 01409, 9 April 2019 By Catherine Fairbairn "No-fault divorce" Contents: 1. The current basis for divorce in England and Wales 2. Owens v Owens: consideration of “behaviour” fact 3. Family Law Act 1996 Part 2 4. Calls for the introduction of no-fault divorce 5. Arguments against the introduction of no-fault divorce 6. Government consultation 7. Divorce in Scotland www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Contents Summary 3 1. The current basis for divorce in England and Wales 5 1.1 Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 5 1.2 Fault based petitions 6 1.3 Divorce process 7 2. Owens v Owens: consideration of “behaviour” fact 9 2.1 Family Court: no divorce 9 2.2 Court of Appeal: appeal dismissed 9 2.3 Supreme Court: further appeal dismissed 10 3. Family Law Act 1996 Part 2 12 3.1 Law Commission recommendations 12 3.2 Provision for “no-fault divorce” 12 3.3 Pilot schemes 13 3.4 Repeal of Family Law Act 1996 Part 2 14 4. Calls for the introduction of no-fault divorce 15 4.1 Calls for no-fault divorce by senior members of the Judiciary 15 4.2 Research study 16 4.3 Lords Private Member’s Bill 17 4.4 Previous Commons Private Member’s Bill 18 4.5 Labour Party Manifesto 2017 18 4.6 “Family Matters” campaign in The Times 18 4.7 Resolution campaign 19 4.8 Report of the Family Mediation Task Force 20 5. Arguments against the introduction of no-fault divorce 21 5.1 Private Member’s Bill debate 21 5.2 Coalition for Marriage 22 5.3 Baroness Deech: reform financial provision law 22 6. -

Court of Appeal Judgment Template

Neutral Citation Number: [2020] EWCA Civ 190 Case No: B4/2019/2369 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM BIRMINGHAM CIVIL JUSTICE CENTRE THE ORDER OF HHJ TUCKER BM15F00007 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 21/02/2020 Before : THE PRESIDENT OF THE FAMILY DIVISION LORD JUSTICE PETER JACKSON and LORD JUSTICE HADDON-CAVE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Re K (Forced Marriage: Passport Order) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Deirdre Fottrell QC, Seema Kansal and Marlene Cayoun (instructed by National Legal Service Solicitors) for the Appellant Jason Beer QC and Alice Meredith (instructed by Staffordshire and West Midlands Police Joint Legal Department) for the Respondent Sarah Hannett (instructed by the Government Legal Department) for the First Intervener the Secretary of State for Justice Henry Setright QC and Jacqueline Renton (instructed by Southall Black Sisters) for the Second Intervener Hearing date : 27th November 2019 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Re K (Forced Marriage: Passport Order) Sir Andrew McFarlane P : 1. In this appeal the court is required to consider the jurisdiction of the Family Court in respect of two issues related to Forced Marriage Protection Orders [‘FMPO’] made under Family Law Act 1996, s 63A. The first relates to the court’s jurisdiction where the subject of the order is an adult who does not lack mental capacity. The second relates to Passport Orders as part of a FMPO, and, in particular, whether there is jurisdiction to make an open-ended or indefinite Passport Order in that context. 2. The factual background to the application can be stated shortly. -

1 VIEW from the PRESIDENT's CHAMBERS (11) the Process of Reform: on the Cusp of History Sir James Munby, P

VIEW FROM THE PRESIDENT’S CHAMBERS (11) The process of reform: on the cusp of history Sir James Munby, President of the Family Division We stand on the cusp of history. 22 April 2014 marks the largest reform of the family justice system any of us have seen or will see in our professional lifetimes. On 22 April 2014 almost all the relevant provisions of the Crime and Courts Act 2013 and the Children and Families Act 2014 come into force. On 22 April 2014 the Family Court comes into existence and the Family Proceedings Court passes into history. On 22 April 2014 we see the implementation of the final version of the revised PLO in public law cases (PLO 2014) and the implementation in private law cases of the Child Arrangements Programme (CAP 2014). Taken as a whole, these reforms amount to a revolution. Central to this revolution has been – has had to be – a fundamental change in the cultures of the family courts. This is truly a cultural revolution. There are many whose contribution to this revolution needs to be recognised and marked. Pride of place must go to David Norgrove, the mastermind of the Family Justice Review. Only those who have worked closely with him will know just how inspired and inspirational his work has been – and continues to be. His achievement has been colossal. It is little over four years ago that the Family Justice Review was set up. In that short time it has reported, it has seen its recommendations accepted first by Government and then by Parliament and then implemented under the collaborative leadership of the judiciary and the Family Justice Board, also chaired by Norgrove. -

President of the Family Division Speech

SIR NICHOLAS WALL, PRESIDENT OF THE FAMILY DIVISION ANNUAL RESOLUTION CONFERENCE THE QUEENS HOTEL, LEEDS 24 MARCH 2012 1. May I begin, not only by thanking you for inviting me to give this keynote address, but also by emphasising the importance of an organisation such as Resolution both to family Law in general and to the judiciary in particular. I fully appreciate, of course and as your name suggests, that you are committed to the non-adversarial resolution of family disputes and it is an unfortunate fact, I think, that the Family Justice System has been grafted on to the adversarial common law structure, Thus, however inquisitorial we try to be, there are some issues of fact, particularly in public law, which have to be decided adversarially. The threshold criteria under section 31 of the Children Act 1989 is an obvious example, as is the fact of non-accidental injury to a child, which the parents deny. We have not found a different way of dealing with such issues, and the law relating to disclosure of documents to the police militates against frank admissions of responsibility for actions which may, in some cases, be both untypical and momentary 2. Nonetheless. I am acutely aware of the damage which ongoing adversarial litigation can do – particularly to children – and it is therefore very useful for me, as a judge, who has spent much of his working life in the adversarial system, to come to a conference such as this, which advocates a different approach. I am only sorry that I could not be with you yesterday in order to attend your workshops. -

Transparency in the Family Court: What Goes on Behind Closed Doors?

24 May 2018 Transparency in the Family Court: What Goes on Behind Closed Doors? PROFESSOR JO DELAHUNTY QC Questions: • Who does the child’s story belong to in the family court? The child, the family or society? • What do the public know about the way family courts make their decisions? • Where and how do we draw the line between confidentiality and press access to the litigation and publication about it? • Is the balance right? • If it is: how do we explain the howls of outrage about “secret courts’ and injustice’ that bleed into public consciousness through social media and some press headlines? • Does the Family Justice System risk falling into disrespect if it does not constructively engage with the public and press? • What next? A History Lesson I have practiced as a barrister for 32 years and been a child protection specialist for about 25 of them. That means I inherited a way of working that operated without mobiles, e-mail, twitter, Facebook etc. Social media (a term not in use) was more likely to mean picking up a scruffy paper in a pub over a pint than the mass explosion of information and views on matters great and small via the world-wide web that we have now. If they got caught up in a child protection case, a parent’s knowledge about what might happen in court as they walked through its doors for the first time would come from the lawyers who worked in the system or anecdote if family or friends had trod the same path before. -

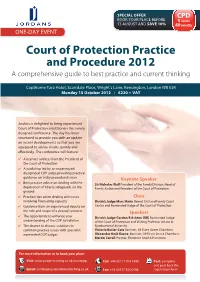

Court of Protection Practice and Procedure 2012 a Comprehensive Guide to Best Practice and Current Thinking

SPECIAL OFFER CPD BOOK YOUR PLACE BEFORE 5 HOURS 13 AUGUST AND SAVE 10% 40 MINUTES ONE-DAY EVENT Court of Protection Practice and Procedure 2012 A comprehensive guide to best practice and current thinking Copthorne Tara Hotel, Scarsdale Place, Wright’s Lane, Kensington, London W8 5SR Monday 15 October 2012 • £220 + VAT Jordans is delighted to bring experienced Court of Protection practitioners this newly designed conference. The day has been structured to provide you with an update on recent developments so that you are equipped to advise clients quickly and effectively. The conference will feature: 4 A keynote address from the President of the Court of Protection 4 A workshop led by an experienced designated COP judge providing practical guidance on tricky procedural issues Keynote Speaker 4 Best practice advice on dealing with the Sir Nicholas Wall President of the Family Division, Head of deprivation of liberty safeguards on the Family Justice and President of the Court of Protection ground 4 P ractical tips when dealing with cases Chair involving fluctuating capacity District Judge Marc Marin Barnet Civil and Family Court 4 G uidance from an experienced deputy on Centre and Nominated Judge of the Court of Protection the role and scope of a deputy’s powers Speakers 4 The opportunity to enhance your District Judge Gordon R Ashton OBE Nominated Judge understanding of the COP jurisdiction of the Court of Protection and Visiting Professor in Law at 4 T he chance to discuss solutions to Northumbria University common practice issues with -

Extended Material Chapter 14: Family Courts

Dodd & Hanna: McNae’s Essential Law for Journalists, 24th edition Extended material Chapter 14: Family courts Chapter summary Family law, a branch of civil law, includes many cases involving disputes between estranged parents after marital breakdown - for example, about contact with a child, or those brought by local authorities seeking to protect children. A court can remove a child from his/her parents because of suspected abuse or neglect. Reporting restrictions and contempt of court law severely limit what the media can publish about most family cases, to protect those involved, particularly children, who in most instances cannot be identified in media reports. Critics say the family justice system is over-secretive. This chapter examines the main restrictions, including those covering divorce cases. 14.1 Introduction The term ‘family cases’ covers a range of matters in civil law. They have in the past been dealt with by magistrates’ courts, county courts, or the High Court Family Division, with cases transferred between these courts. But a new Family Court began operating in April 2014, amalgamating this system into one, unified court. It operates from existing courthouses, with a role for magistrates and with judges continuing to preside in the most complex cases. The family justice system has critics. Groups such as Families Need Fathers claim that judges are biased in favour of mothers in disputes over contact with children. Other groups say these courts do not do enough to protect mothers and children from coercive, violent fathers. And there is concern that miscarriages of justice could occur when courts approve the removal of children from their parents, such as when there is disputed medical evidence of abuse. -

Family Justice Council Annual Report 2011-12 Contents

Family Justice Council Annual Report 2011-12 Family Justice Council Annual Report 2011-12 Contents Contents Foreword by the President, Sir James Munby 3 1: How the Council works 5 2: Overview of Activities and Issues in 2011-12 8 3: The Children in Families Committee 9 4: The Children in Safeguarding Proceedings Committee 12 5: The Money & Property Committee 15 6: The Diversity Committee 17 7: The Experts Committee 19 8: Voice of the Child Sub-Group 21 9: The Domestic Abuse Committee 24 10: The Parents and Relatives Group 27 11: The Local Family Justice Councils 29 12: The Dartington Hall Conference 32 13: Challenges for 2012-13 34 Annex A: Terms of Reference 36 Annex B: Membership 37 Annex C: Expenditure 2011-12 and Budget for 2012-13 48 Annex D: Report on Business Plan 2011-12 50 Annex E: Family Justice Council: 2012-13 Business Plan 54 2 Family Justice Council Annual Report 2011-12 Foreword Foreword by the President, Sir James Munby This is the seventh annual report of the Family Justice Council and saw the Council publish several documents setting out valuable guidance on a range of issues. One of the Council’s key functions is to identify issues which require guidance and to consider and propose best practice. During the year covered by this report the Council published: guidance on children giving evidence in family proceedings; guidance on the conduct of Financial Dispute Resolution hearings in financial proceedings; best practice on the use of Multi- Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARACs) in family proceedings; a protocol on the service of non-molestation orders, and; guidelines on the use of overseas experts in family proceedings. -

Judicial Cooperation with Serious Case Reviews

President’s Guidance Judicial Cooperation with Serious Case Reviews Dated 2 May 2017 1. It is apparent that there is widespread misunderstanding as to the extent to which judges (which for this purpose includes magistrates) can properly participate in Serious Case Reviews (SCRs). The purpose of this Guidance is to clarify the position and to explain what judges can and cannot do. 2. This guidance applies to all judges sitting in the Family Division or the Family Court, including Magistrates and, where exercising judicial functions, Legal Advisers. 3. Judges should provide every assistance to SCRs which is compatible with judicial independence. It is, however, necessary to be aware that key constitutional principles of judicial independence, the separation of powers and the rule of law can be raised by SCRs. Background 4. From time to time, judges are asked to participate in various ways in SCRs following the death of a child where there has been contact with Local Authority Children’s Services. SCRs are conducted by Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs). These are statutory bodies, established by the Children Act 2004, with chairs independent of the Local Authority they scrutinise – usually a senior social work manager from another Local Authority. 5. On occasions LSCBs have written to judges after child deaths to request either an interview or the completion of an Independent Management Review (IMR). An IMR is a detailed review of an agency’s involvement with a child and is one of the principal means of capturing information for use in SCRs. Sometimes LSCBs write with a list of specific questions which they invite the judge to answer. -

Court of Protection Report 2010

Court of Protection Report 2010 CONTENTS Contents ....................................................................................................................1 Foreword by the senior judge ...................................................................................2 1 Judiciary..................................................................................................................4 2 Court administration..............................................................................................5 3 Work of the court ...................................................................................................6 4 Review of performance ..........................................................................................9 5 Case law................................................................................................................ 12 6 Volume of business ..............................................................................................24 Appendix A Court of Protection judiciary ..............................................................27 Appendix B Court leadership ................................................................................. 31 Appendix C Court User Group ..............................................................................32 - 1 - Foreword by the senior judge There were some changes in key personnel in the court during 2010. Following Sir Mark Potter’s retirement at the end of March, Sir Nicholas Wall was appointed as President of both the Family -

Reforming the Lord Chancellor's Role in Senior Judicial Appointments

Reforming the Lord Chancellor’s Role in Senior Judicial Appointments Richard Ekins and Graham Gee Foreword by Rt Hon Jack Straw Reforming the Lord Chancellor’s Role in Senior Judicial Appointments Richard Ekins and Graham Gee Foreword by Rt Hon Jack Straw Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Registered charity no: 1096300. Trustees Diana Berry, Alexander Downer, Pamela Dow, Andrew Feldman, David Harding, Patricia Hodgson, Greta Jones, Edward Lee, Charlotte Metcalf, David Ord, Roger Orf, Andrew Roberts, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, William Salomon, Peter Wall, Simon Wolfson, Nigel Wright. Reforming the Lord Chancellor’s Role in Senior Judicial Appointments About the Authors Richard Ekins is Head of Policy Exchange’s Judicial Power Project and Professor of Law and Constitutional Government, St John’s College, University of Oxford. His published work includes The Nature of Legislative Intent (OUP, 2012) and the co-authored book Legislated Rights: Securing Human Rights through Legislation (CUP, 2018). -

From “Form” to Function and Back Again: a Comparative Analysis of Form-Based and Function-Based Recognition of Adult Relationships in Law

From “form” to function and back again: a comparative analysis of form-based and function-based recognition of adult relationships in law. Kathy Griffiths Cardiff School of Law and Politics Cardiff University Submitted for examination: May 2017 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed …K Griffiths…………………………………………… (candidate) Date …10/08/2017…….…………….……… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Signed …K Griffiths…………………………….…………… (candidate) Date …10/08/2017………………….…………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated, and the thesis has not been edited by a third party beyond what is permitted by Cardiff University’s Policy on the Use of Third Party Editors by Research Degree Students. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …K Griffiths…………………………….……….…… (candidate) Date …10/08/2017………….………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed …K Griffiths…………………………………………..…..….. (candidate) Date …10/08/2017…………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available online in the University’s Open Access repository and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee.