5020 10 Comm Rail Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1St

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1st Generation DMU’s for British Railways A Review Rodger P. Bradley Gloucester RC&W Co.’s Diesel Multiple Units Rodger P Bradley As we know the history of the design and operation of diesel – or is it oil-engine powered? – multiple unit trains can be traced back well beyond nationalisation in 1948, although their use was not widespread in Britain until the mid 1950s. Today, we can see their most recent developments in the fixed formation sets operated over long distance routes on today’s networks, such as those of the Virgin Voyager design. It can be argued that the real ancestry can be seen in such as the experimental Michelin railcar and the Beardmore 3-car unit for the LMS in the 1930s, and the various streamlined GWR railcars of the same period. Whilst the idea of a self-propelled passenger vehicle, in the shape of numerous steam rail motors, was adopted by a number of the pre- grouping companies from around the turn of the 19th/20th century. (The earliest steam motor coach can be traced to 1847 – at the height of the so-called to modernise the rail network and its stock. ‘Railway Mania’.). However, perhaps in some ways surprisingly, the opportunity was not taken to introduce any new First of the “modern” multiple unit designs were techniques in design or construction methods, and built at Derby Works and introduced in 1954, as the majority of the early types were built on a the ‘lightweight’ series, and until 1956, only BR and traditional 57ft 0ins underframe. -

Planning Committee Report REPORT

Planning Committee Report REPORT SUMMARY REFERENCE NO - 18/502379/LBC APPLICATION PROPOSAL Listed Building application for proposed upgrade of Network Rail's East Farleigh Level Crossing from a Manned Gated Hand Worked (MGHW) Level Crossing to a Manually Controlled Barrier(s) (MCB) type (Resubmission). ADDRESS East Farleigh Mghw Level Crossing Farleigh Lane Farleigh Bridge East Farleigh Maidstone Kent ME16 9NB RECOMMENDATION – Grant Listed Building Consent SUMMARY OF REASONS FOR RECOMMENDATION for approval The level crossing gates do not form part of the main listing for the East Farleigh railway station; The level crossing gates do not appear to be curtilage listed structures, as they constructed after the 1948; Any harm to the character, integrity and setting of the Listed Building, would be outweighed the public safety benefit; The erection of the new level crossing gates does not require Listed Building Consent. REASON FOR REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE Teston Parish Council wishes to see the application refused and request that the application be reported to Planning Committee for the reasons set out in their consultation response. (Note – The site lies with Barming Parish, not Teston Parish) WARD Barming And PARISH/TOWN APPLICANT Network Rail Teston COUNCIL Barming Infrastructure Limited AGENT Network Rail Infrastructure Limited DECISION DUE DATE PUBLICITY EXPIRY OFFICER SITE VISIT 27/06/18 DATE DATE 22/06/18 01/06/18 RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY (including appeals and relevant history on adjoining sites): App No Proposal Decision Date 17/506600/LBC Listed Building Consent for the upgrade Withdraw 26/2/201 of the level crossing n 8 15/504142/LBC Listed Building Consent - Replacement of Approved 14/7/201 station roof covering 5 MAIN REPORT 1.0 DESCRIPTION OF SITE 1.01 East Farleigh station lies along Farleigh Lane and just to the north of the River Medway. -

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Durham Dales Map

Durham Dales Map Boundary of North Pennines A68 Area of Outstanding Natural Barleyhill Derwent Reservoir Newcastle Airport Beauty Shotley northumberland To Hexham Pennine Way Pow Hill BridgeConsett Country Park Weardale Way Blanchland Edmundbyers A692 Teesdale Way Castleside A691 Templetown C2C (Sea to Sea) Cycle Route Lanchester Muggleswick W2W (Walney to Wear) Cycle Killhope, C2C Cycle Route B6278 Route The North of Vale of Weardale Railway England Lead Allenheads Rookhope Waskerley Reservoir A68 Mining Museum Roads A689 HedleyhopeDurham Fell weardale Rivers To M6 Penrith The Durham North Nature Reserve Dales Centre Pennines Durham City Places of Interest Cowshill Weardale Way Tunstall AONB To A690 Durham City Place Names Wearhead Ireshopeburn Stanhope Reservoir Burnhope Reservoir Tow Law A690 Visitor Information Points Westgate Wolsingham Durham Weardale Museum Eastgate A689 Train S St. John’s Frosterley & High House Chapel Chapel Crook B6277 north pennines area of outstanding natural beauty Durham Dales Willington Fir Tree Langdon Beck Ettersgill Redford Cow Green Reservoir teesdale Hamsterley Forest in Teesdale Forest High Force A68 B6278 Hamsterley Cauldron Snout Gibson’s Cave BishopAuckland Teesdale Way NewbigginBowlees Visitor Centre Witton-le-Wear AucklandCastle Low Force Pennine Moor House Woodland ButterknowleWest Auckland Way National Nature Lynesack B6282 Reserve Eggleston Hall Evenwood Middleton-in-Teesdale Gardens Cockfield Fell Mickleton A688 W2W Cycle Route Grassholme Reservoir Raby Castle A68 Romaldkirk B6279 Grassholme Selset Reservoir Staindrop Ingleton tees Hannah’s The B6276 Hury Hury Reservoir Bowes Meadow Streatlam Headlam valley Cotherstone Museum cumbria North Balderhead Stainton RiverGainford Tees Lartington Stainmore Reservoir Blackton A67 Reservoir Barnard Castle Darlington A67 Egglestone Abbey Thorpe Farm Centre Bowes Castle A66 Greta Bridge To A1 Scotch Corner A688 Rokeby To Brough Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2015. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Great Ideas for Discovering the Best of the Broads by Cycle

Great ideas for discovering the best of the Broads by cycle • On-road cycling routes using quiet lanes, and traffic-free cycle ways • Tips on where to cycle, taking your bike on a train and bus, and where to stop off Use a cycle to explore the tranquil beauty and natural treasures of the wetland landscapes that make up the Broads – a unique area characterised by windmills, grazing marshes, boating scenes, vast skies, reedy waters and historic settlements. There are idyllically quiet lanes and virtually no hills. If you’re touring the Broads by boat, you can stop off for a while and hire bikes from several places by the water, and see some of the area’s many other attractions. Cycling in the Broads gets you to places public transport cannot reach, and you see much that you might otherwise miss from a car or even a boat. It’s also a healthy and environmentally friendly way of getting around. Centre: How Hill (photo: Tim Locke); left and right: cycling round the Broads (photos: Broads Authority) Contents An introduction to discovering the Broads by bike, offering several itineraries in one. It starts with details of using the Bittern Line to get you to Hoveton & Wroxham, where you can hire a bike and follow Broads Bike Trails, or cycle alongside the Bure Valley Railway; how to join up with the BroadsHopper bus from rail stations; ideas for cycling in the Ludham and Hickling area; and some highlights of Sustrans NCN Route 1 from Norwich. The Broads Bike Hire Network of seven cycle hirers is listed in the last section. -

List of Periodicals

Railway Studies Collection : list of periodicals The following is a list of periodicals and newsletters currently held in the Railway Studies Collection in Newton Abbot Library. A Archive * No 1, 1994 to date Association of Railway Preservation Societies Newsletters/Journals Nos 1-40,56-121, 123-155, 160-208, 212-225 Atlantic Coast Express* (see also Bideford & Instow Railway Group No 13, 21, 22, 40, 42-63, 65, 81 & 83 to date B Back Track * No 1, 1987 to date Barrowmore Model Railway Journal No 1 to date Beyer Peacock Quarterly Review 1927-32 Bideford & Instow Railway Group (continued as Atlantic Coast (to No. 21) Express) Big Four (Worcester Locomotive Society) Nos 35/38 Bishop’s Castle Railway Society Journal Nos 6-10, Black Eight (Stanier 8F Locomotive Society) Nos 3, 43-66, 68, 71,73,74,86, 90-92,95 Blastpipe (Scottish RPS) 1975 to 1980 – 2007 Bluebell News (Kent and East Sussex Railway) Summer 1979, 1980/81 & 1990 to date Bodmin and Wenford News (B & WRPS) No 13, 1990 to date Nos 103-201 & 203-205, 209 – 264 & 1972- Branch Line News 1975 to date Branch Line Review Mar, Jul 1964, Jan, Apr 1965 Autumn ’94, Jul, Oct ’94, Mar, Oct ’96. Mar, Bridgend Valleys Railway Society Newsletter Nov ‘97 The Brighton Circular (L.B.S.C.R.) 1975 to date British Railway Journal * No 1 1983 to date Apr 1993, May 1994, Dec 1995, Jun 1999, Jul British Railway Modelling 2001, Apr 2002, Oct 2005. British Railways Historical Study Group No 1 1977 to 1980 British Railways Illustrated * No 1 1991 to date British Railways Magazine Eastern Region – CD 1948 - 1963 British Railways Magazine Southern Region Feb - Jun 1963 British Railways Southern Region Magazine 1949, vol 2 no 12 1951, vol 5 no 7 1954 British Steam Railways Nos 7,9,10 2004, No 17 2005 1948-49, Nos 1,5 1953, 1957-58, 1959-60 vol.6 no.3 1955, vol.8 nos 1-12 1957, vol11 no B. -

Picturesque Traditional Brick and Flint Coastal Property

PICTURESQUE TRADITIONAL BRICK AND FLINT COASTAL PROPERTY ST. SAVA WEST RUNTON, NORFOLK PICTURESQUE TRADITIONAL BRICK AND FLINT PROPERTY IN THIS POPULAR COASTAL VILLAGE ST. SAVA WEST RUNTON, NORFOLK, NR27 9QJ Entrance hall w sitting room w dining room w garden room kitchen/breakfast room w five bedrooms w shower room garage WC/cloakroom, gravelled off street parking, mature garden w in all about 0.1 of an acre w EPC rating = D The Property St. Sava is a picturesque semi detached property, traditionally constructed of brick and flint under a pantiled roof as one of a pair of cottages believed to date from the Edwardian era. The house has spacious and well-arranged accommodation over three floors with fine south westerly views over the garden to countryside beyond forming part of the North Norfolk Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). The property has been in the ownership of the same family since the 1980s and was re-wired about three years ago, the current occupant has lived here since 2007. The property is situated off a private un- adopted road just inland from the coast. Outside The house can be approached by a private un-adopted road either from the north or the south. To the rear and south of the house a pair of white painted gates and a brick and flint wall lead onto a gravelled parking area where there is also an up-and-over doorway access to the garage. There is a pedestrian access down the side of the house which leads to a very pretty garden largely laid to lawn with well stocked mixed shrub and herbaceous beds and a variety of ornamental shrubs and trees. -

20/20 Vision

THE DARTMOOR PONY The Magazine of the Dartmoor Railway Supporters’ Association No.35 Winter 2018/19 £2.00 20/20 Vision The DARTMOOR PONY Issue No. 35 Editor: John Caesar E-mail: [email protected] DARTMOOR RAILWAY SUPPORTERS’ ASSOCIATION Website: www.dartmoor-railway-sa.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/dartmoorrailway.sa Postal Address: Jon Kelsey, Craig House, Western Rd, Crediton, EX17 3NB E-mail: [email protected] The views expressed in the newsletter are not necessarily those of the Dartmoor Railway Supporters’ Association. FRONT COVER:. Class 20s 20142 'Sir John Betjeman' and 20189 at Okehampton station, with the Loram railgrinder in the background on 9th January 2019. Photo: Paul Martin. BACK COVER: Top: The 'Train to Christmas Town', headed by 31452 with D4167 on the rear, at Meldon Quarry road 12 on 8th December 2018. Photo: Dave Hunt. Bottom: One car of the rail grinder, having been dragged to Meldon to await a low loader on 17th January 2019 to take it to the Laira wheel lathe. Photo: Geoff Horner. 2 The Dartmoor Pony Winter 2018/19 CONTENTS Notes from the Chairman Page 4 Membership Matters Page 5 Peter Ritchie Page 6 Martin Stephens-Hodge Page 8 Trevor Knight Page 8 Cyril Pawley Page 9 2019 Annual General Meeting Page 9 Events Page 9 Rail Operations & Line Update Page 10 Dartmoor Railway Timetable 2019 Page 12 OkeRail update Page 13 Volunteer Activities Page 14 Station Maintenance Team Page 18 Station Gardening Page 20 Memories of the Last Rail Freight Traffic at Okehampton Page 22 The Area Manager takes a cab ride to Meldon Page 25 Last Revenue Earning Train through Tavistock North Page 26 Rosie’s Diary Page 28 The Dartmoor Pony Winter 2018/19 3 Notes from the Chairman Rev. -

Hoveton & Wroxham Station Improvements

Broads Local Access Forum 2 March 2016 Agenda Item 10 Hoveton & Wroxham Station Improvements Three Years On Chris Wood Community Rail Norfolk Draft - November 2015 Community Rail Norfolk is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England, no. 07712720. Registered office: c/o Broadland District Council, Thorpe Lodge, 1 Yarmouth Road, Norwich NR7 0DU. For 2015/16 we have received core funding from Abellio Greater Anglia, Suffolk County, Great Yarmouth Borough, Cromer Town, N Walsham Town, North Norfolk, Waveney and South Norfolk District Councils. 1 1 Introduction A variety of interests are focussed on improving the environment at Hoveton & Wroxham station and on making it into a Gateway to the Broads. This project began in 2012 and received a major boost in 2013 through the Greater Anglia station refresh and EU STEP- funded work to brighten up the platforms, facilitated by the Broads Authority, but there has been no significant progress on keeping paths clear, signage or the subway, and the death of the proprietor of the Chinese restaurant has been a set-back. This paper sets out progress to date, lists issues still of concern, and attempts to set out a basis for the next steps. 2 Progress on key elements of the project 2.1 Station renewal as part of the Greater Anglia franchise commitment, including previously neglected items, particularly the canopies. 2.1.1 The canopies were painted in 2013, but are already looking tired again. 2.1.2 The problems with the guttering on the Sheringham-bound platform superstructure (especially the lack of down-pipe) have not been addressed, so that rain still soaks the brickwork. -

Annex 9 Draft Reply to the Consultation on Rail Action Plan for Kent

Annex 9 Draft reply to the Consultation on Rail Action Plan for Kent Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council welcomes the Rail Action Plan for Kent and wishes to support this document, subject to some additional comments. The Rail Forum staged by the County Council last November was excellent and it put the rail industry, the train operating company, Network Rail and the Department for Transport (DfT) on notice that the County Council, the District Councils and Parish Councils of Kent together with the many rail user groups were all deeply serious and motivated about the next franchise. Between then and now we have had the swingeing increases in fares and the poor performance of Southeastern Railway over the winter period to further reinforce everyone’s intention that next time it will be better and that there will be a sharper focus on the emerging specification for the next franchise and a closer scrutiny of the commissioning process. The draft Plan is admirably comprehensive and pays good attention to the needs of rail passengers in West Kent. The key issues that concern us are well covered. Services on the West Malling/Maidstone line are highlighted. The importance of fares, timetables and service performance are well to the fore. The following comments are not a criticism; just a pointer to what we believe will make the coverage of the document that bit more complete as far as the needs of this area are concerned. • The mention of high speed services on the Medway Valley line is welcome. We should include the need for a stop within this Borough. -

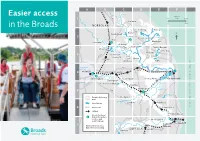

Easier Access Guide

A B C D E F R Ant Easier access A149 approx. 1 0 scale 4.3m R Bure Stalham 0 7km in the Broads NORFOLK A149 Hickling Horsey Barton Neatishead How Hill 2 Potter Heigham R Thurne Hoveton Horstead Martham Horning A1 062 Ludham Trinity Broads Wroxham Ormesby Rollesby 3 Cockshoot A1151 Ranworth Salhouse South Upton Walsham Filby R Wensum A47 R Bure Acle A47 4 Norwich Postwick Brundall R Yare Breydon Whitlingham Buckenham Berney Arms Water Gt Yarmouth Surlingham Rockland St Mary Cantley R Yare A146 Reedham 5 R Waveney A143 A12 Broads Authority Chedgrave area river/broad R Chet Loddon Haddiscoe 6 main road Somerleyton railway A143 Oulton Broad Broads National Park information centres and Worlingham yacht stations R Waveney Carlton Lowesto 7 Grid references (e.g. Marshes C2) refer to this map SUFFOLK Beccles Bungay A146 Welcome to People to help you Public transport the Broads National Park Broads Authority Buses Yare House, 62-64 Thorpe Road For all bus services in the Broads contact There’s something magical about water and Norwich NR1 1RY traveline 0871 200 2233 access is getting easier, with boats to suit 01603 610734 www.travelinesoutheast.org.uk all tastes, whether you want to sit back and www.broads-authority.gov.uk enjoy the ride or have a go yourself. www.VisitTheBroads.co.uk Trains If you prefer ‘dry’ land, easy access paths and From Norwich the Bittern Line goes north Broads National Park information centres boardwalks, many of which are on nature through Wroxham and the Wherry Lines go reserves, are often the best way to explore • Whitlingham Visitor Centre east to Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft.