USADA V. Montgomery: Paving a New Path to Conviction in Olympic Doping Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Track Superstar Marion Jones' Duty and Liability to Her Olympic Relay Teammates

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 2008 Article 4 Passing the Baton: Track Superstar Marion Jones' Duty and Liability to Her Olympic Relay Teammates Jolyn R. Huen Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Jolyn R. Huen, Passing the Baton: Track Superstar Marion Jones' Duty and Liability to Her Olympic Relay Teammates, 5 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 39 (2008) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol5/iss1/4 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PASSING THE BATON: TRACK SUPERSTAR MARION JONES' DUTY AND LIABILITY TO HER OLYMPIC RELAY TEAMMATES I. INTRODUCTION In October of 2007, millions of avid sports fanatics, track and field aficionados, and Marion Jones enthusiasts felt the pain of their hearts breaking as the gold medal track star admitted to taking performance enhancing drugs.' The Olympian confessed to ingesting the steroid tetrahydrogestrinone (THG or "the clear") before the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia. 2 After seven years of denial, Marion Jones pled guilty to lying to federal investigators about using the ster- oids and was subsequently punished by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and the International Olympic Com- mittee (IOC).3 The question then remains: -

For Release, December 16, 1998 Contact

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kelsey Rhoney (312-729-3685) GATORADE® NATIONAL GIRLS TRACK & FIELD ATHLETE OF THE YEAR: KATELYN TUOHY 2016-2017 National Girls Track & Field Winner and Female Athlete of the Year Sydney McLaughlin Surprises Winner with Honor Thiells, NY. (June 26, 2018) – In its 33rd year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, The Gatorade Company today announced Katelyn Tuohy of North Rockland High School (Thiells, NY) as its 2017-18 Gatorade National Girls Track & Field Athlete of the Year. Tuohy was surprised with the news by 2016-2017 National Girls Track & Field Winner and Female Athlete of the Year Sydney McLaughlin. Tuohy is the first athlete in history to win the Gatorade Player of the Year national title for two different sports, cross country and track & field. Check out the surprise video here. “With national records from the mile to the 5,000 meters, Katelyn Tuohy has reached a level in high school distance running that we’ve seen only once before, with Mary Cain a few years ago,” said Doug Binder, Editor-in-Chief for Dyestat.com. “But to do this as a sophomore, Katelyn’s even beyond Mary’s level of accomplishment. No one in modern times has ever held the outdoor high school records in both the mile and the 2-mile [converted from her national record in the 3200], and Tuohy got both records in high school-only races where she had to do all of the work. Her record-breaking mile in 90-degree heat in North Carolina this June is one of the most impressive things I’ve ever seen.” The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Tuohy as the nation’s best female high school track & field athlete. -

Division I Women's Indoor Track Championships

DIVISION I WOMEN’S INDOOR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS RECORDS BOOK 2015 Championship 2 History 5 All-Time Results 17 2015 CHAMPIONSHIP HIGHLIGHTS Arkansas wins first national championship: The top-ranked University of Arkansas women’s track and field team made history Saturday night at the Randal Tyson Track Center with the program’s first national championship. The victory is also the first at the Division I level for head coach Lance Harter and the first for any women’s program at Arkansas. The Razorbacks won three national event titles during the weekend to score a program-best 63 points atop the team standings. Prior to Saturday’s result, the program had a previous high finish of third place at the 2000 national meet in Fayetteville. The Razorbacks entered the meet with a top-five finish in three of the previous four years before ascending to the top of the team podium. With 63 points, the Razorbacks posted the third-highest team total in meet history. Arkansas scored 50 of its points Saturday. Doubling back from Friday’s anchor of the victorious distance-medley relay, Scott claimed her first NCAA individual title with a first-place run at 3,000 meters. The Razorback senior crossed the finish line to a standing ovation from the home crowd in a time of 8:55.19, more than three seconds ahead of the runner-up. Scott is the second runner in program history to win an indoor title at 3,000 meters, joining Sarah Schwald who won in 1995. Morris tied the NCAA indoor meet record in her victory in the pole vault, posting a final clearance of 4.60m/15-1. -

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I Women’S

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I WOMEN’S Highlights Lady Vols show world-class distance dominance: Tennessee dominated Division I women’s indoor track March 13-14 – and dominated the world for more than 10 minutes. The Lady Vols captured the school’s second team title in five years at the Division I Women’s Indoor Track and Field Championships and won two events during competition at Texas A&M – including a victory in world-record time in the distance medley relay. Tennessee’s time of 10 minutes, 50.98 seconds, in that event sliced more than three seconds off Villanova’s 21-year-old world mark in the 1,200-/400-/800-/1,600-meter medley, and eight seconds off UCLA’s 2002 meet record. The relay squad was anchored for the second straight year by Sarah Bowman, who figured in both Lady Vols’ event titles and collected a second meet record when she out- leaned Texas Tech’s Sally Kipyego to win the mile run. “Oh, my gosh, look at what we’ve done this weekend,” said Bowman, who also was a member of the 2005 indoor championship team. “I couldn’t ask for a sweeter weekend my senior year. I can’t even put it into words. It’s so amazing. “The heart that this team has, I could actually tear up just talking about them. Just to be out here with these girls who are putting their hearts on the line for the team, and it makes you want to do it all the more. It’s awesome to be part of a team like that.” Tennessee coach J.J. -

Media Kit Contents

2005 IAAF World Outdoor Track & Field Championship in Athletics August 6-14, 2005, Helsinki, Finland Saturday, August 06, 2005 Monday, August 08, 2005 Morning session Afternoon session Time Event Round Time Event Round Status 10:05 W Triple Jump QUALIFICATION 18:40 M Hammer FINAL 10:10 W 100m Hurdles HEPTATHLON 18:50 W 100m SEMI-FINAL 10:15 M Shot Put QUALIFICATION 19:10 W High Jump FINAL 10:45 M 100m HEATS 19:20 M 10,000m FINAL 11:15 M Hammer QUALIFICATION A 20:05 M 1500m SEMI-FINAL 11:20 W High Jump HEPTATHLON 20:35 W 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 12:05 W 3000m Steeplechase HEATS 21:00 W 400m SEMI-FINAL 12:45 W 800m HEATS 21:35 W 100m FINAL 12:45 M Hammer QUALIFICATION B Tuesday, August 09, 2005 13:35 M 400m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 13:55 W Shot Put HEPTATHLON 11:35 M 100m DECATHLON\ Afternoon session 11:45 M Javelin QUALIFICATION A 18:35 M Discus QUALIFICATION A 12:10 M Pole Vault QUALIFICATION 18:40 M 20km Race Walking FINAL 12:20 M 200m HEATS 18:45 M 100m QUARTER-FINAL 12:40 M Long Jump DECATHLON 19:25 W 200m HEPTATHLON 13:20 M Javelin QUALIFICATION B 19:30 W High Jump QUALIFICATION 13:40 M 400m HEATS 20:05 M Discus QUALIFICATION B Afternoon session 20:30 M 1500m HEATS 14:15 W Long Jump QUALIFICATION 20:55 M Shot Put FINAL 14:25 M Shot Put DECATHLON 21:15 W 10,000m FINAL 17:30 M High Jump DECATHLON 18:35 W Discus FINAL Sunday, August 07, 2005 18:40 W 100m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 19:25 M 200m QUARTER-FINAL 11:35 W 20km Race Walking FINAL 20:00 M 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 11:45 W Discus QUALIFICATION 20:15 M Triple Jump QUALIFICATION -

December 31, 2010}

Volume 12, Number 2 {coverage from July 1 Æ December 31, 2010} AMERICAN ARBITRATION ASSOCIATION DECISIONS United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) v. LaShawn Merritt, AAA No. 771900029310 (Oct., 2010). Merritt tested positive for the prohibited substance DHEA and pregnenolone three separate times. Merritt claims that he ingested the substance by accident, but he does admit that he tested positive as a result of ingesting ExtenZe, a product used for enhanced sexual performance. USADA agreed that the positive results were caused by ExtenZe, and as such represent an accidental ingestion. The panel found that Merritt was not significantly negligent and reduced the required two-year ineligibility status to twenty-one months, starting October 28, 2009 and ending July 27, 2011. He is also prohibited from participating in and accessing the U.S. Olympic Training Facilities during this period. United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) v. Kirk O’Bee, AAA No. 771900051509JENF (Oct., 2010). Cyclist O’Bee committed his second anti-doping violation when he tested positive for recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO), eight years after testing positive for testosterone. USADA was also able to prove that O’Bee either used or possessed HGH as early as September 2005, and used testosterone after his first suspension. The panel imposed a lifetime suspension and disqualified his cycling results from October 3, 2005 through July 29, 2009, the date of his suspension from the sport. ANTITRUST LAW Race Tires Am., Inc. v. Hoosier Racing Tire Corp., 614 F.3d 57 (3d Cir. 2010). Plaintiff, a specialty tire manufacturer filed a complaint, naming Hoosier (a competitor tire manufacturer) and DMS (a motorsports sanctioning body) as Defendants. -

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I Women’S

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I WOMEN’S Highlights Oregon women claim first indoor track crown: The No. 1-ranked Oregon women made their first Division I NCAA Indoor Track and field National Championship look easy, claiming the title March 13 by piling up 61 points. Defending champ fourth-ranked Tennessee was second with 36 points, followed by No. 3 LSU (35), No. 4 Florida (33) and No. 2 Texas A&M (31). Oregon won without coach Vin Lananna, who was forced to stay in Oregon for medical reasons. The Ducks also overcame a disappointing 13-point first night that left them five points behind leader Auburn. “Their spirits were getting down,” assistant coach Robert Johnson said, “and I was like, ‘Look, you’ve got to stop that getting down and throwing a pity party. We’re still in this thing. As long as you guys rally around each other, we can get this thing done.’” Despite the late-night pep talk, Johnson was unsure if his message had its intended effect. “I didn’t feel so good after the meeting, but when I got to see them this morning their spirits were up,” he said. Brianne Theisen kept the good vibes going, winning the pentathlon and putting the Ducks ahead for good. Jordan Hasay and Anne Kesselring then ran fourth and sixth, respectively, in the mile to give Oregon 31 points. Keshia Baker gave the Ducks all the points they would need with a second-place finish in the 400-meter dash. Francena McCorory of Hampton won the event, setting an American record by finishing in 50.54 seconds. -

Press Release

Tribunal Arbitral du Sport Court of Arbitration for Sport PRESS RELEASE ATHLETICS – WOMEN ’S 4X100 M AND 4X400 M RELAY OF THE 2000 SYDNEY OLYMPIC GAMES THE APPEAL OF THE US ATHLETES IS UPHELD Lausanne, 16 July 2010 - The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) has upheld the appeal filed by the American relay athletes Andrea Anderson, Latasha Colander Clark, Jearl Miles-Clark, Torri Edwards, Chryste Gaines, Monique Hennagan and Passion Richardson (the Athletes) against the decision of the Executive Board of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) of 10 April 2008. Consequently, IOC Executive Board’s decision has been set aside, and on the basis of the IOC and IAAF Rules in force and applicable at the time of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, the CAS Panel has ruled that the United States’ teams that competed in the women’s 4x100m and 4x400m athletics relay events at the Sydney Games shall not be disqualified and the medals and diplomas awarded to the Athletes shall not be returned to the IOC. The Athletes, together with Nanceen Perry and Marion Jones, competed in the 4x100m and/or 4x400m relay events at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. In October 2007, following the so- called ‘BALCO’ case, Marion Jones signed an ‘Acceptance of Sanction’ form in front of the United States Anti-Doping Agency admitting that she had used a prohibited substance during the Sydney Olympic Games and accepted various sanctions including the return of all medals won by her at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Furthermore, the IOC Executive Board decided to disqualify Marion Jones from all track and field events in which she had competed at the Sydney Games, including the 4x100m and 4x400m relay races. -

USATF Championships- Tod Long (Ok) 46.98; 6

_¥.12 (fastest time since '89); 3. Quincy Watts (Niki) 44.24; 4. Andrew • '£!!Iman (Maz} 44.28J11, x A; I-a: 9, x A); 5. Antonio Pettigrew (Reeb) 44.45; 6. Derek • Mills(Gan 44.62 (CL); 7. Darnell Hall (Reeb) 45.26; 8. Lamont Smith (Blinn) 46.47. • (Best-ever marks-for-place: 5-6). HEATS (June 17; qualify 3+4): 1-1. John son 45.62; 2. Mills 45.95; 3. Smith 45.99; 4. Jason Rouser (NikLA) 46.14; 5. Scott Turn er (11)46.16; 6. Anthuan Maybank (la) 46.88; 7. Sean Maye (BYU) 47.29. 11-1.Valmon 45.35; 2. Pettigrew 45.53; 3. Reynolds 46.03; 4. David Knight (laSt) 46.31; 5. Devon Edwards (CPP) 47.13; 6. Wesley Russell (Clem) 47.40. 111-1.Steve Lewis (SMTC) 45.82; 2. Chris Jones (Rice) 46.45; 3. Kevin Lyles (SH) 46.77; 4. Clarence Daniel (unat) 46.79; 5. -USATF Championships- Tod Long (Ok) 46.98; 6. Chip Jenkins (NikA) 47.21; 7. Willie Caldwell (AIA) 47.62. Eugene, June 15-19; breezy, warm 11(2.3)-1.Mltchell 9.96w; 2. Lewis 1o:05; 3: - IV-1. Watts 45-55; 2.-1,all.45 ..69;.3. Aaron (64°-78°), humidity 55-69%. Marsh 10.06; 4. Drummond 10.09; 5. Heard Payne (OhSt) 46.34; 4. Marlin Cannon (StA) Attendance: 42,022 (6/15---6638; 6/16- 10.17; 6. Miller 10.36; 7. Barnes 10.36; 8. 46.48; 5. Gabriel Luke (Rice) 46.57; 6. 7371; 6/17---8055; 6/16-9305; 6/19- Bridgewater 10.37. -

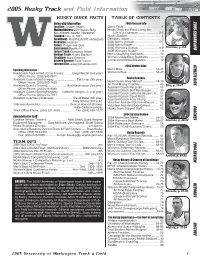

2005 Husky Track and Field Information

2005 Husky Track and Field Information HUSKY QUI CK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2005 SEASON INFO University Information 2005 Season Info Location: Seattle, Wash. Quick Facts ............................................. 1 Mailing Address: 229 Graves Bldg. Husky Track and Field: Living the Box 354070, Seattle, WA 98195 Life of a Champion ........................ 2-3 Founded: Nov. 4, 1861 Husky Stadium ........................................ 4 Enrollment: 36,000 (26,000 undergrad) Dempsey Indoor ...................................... 5 Nickname: Huskies 2005 Men’s Outlook ............................. 6-7 Colors: Purple and Gold 2005 Men’s Roster .................................. 7 Conference: Pacific-10 2005 Women’s Outlook ........................ 8-9 Previews, p. 6-9 Indoor Track: Dempsey Indoor 2005 Women’s Roster ............................. 9 Outdoor Track: Husky Stadium Men’s Qualifying Standards .................. 10 President: Mark Emmert Women’s Qualifying Standards .............. 11 Athletic Director: Conference/NCAA Affiliations................ 12 Todd Turner Internet Site: www.gohuskies.com ATHLETE BIOS COACHES 2004 REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY 2005 Athlete Bios Coaching Information Men’s Bios........................................ 14-31 Head Coach Track & Field / Cross Country: ........ Greg Metcalf (3rd year) Women’s Bios .................................. 32-47 Office Phone: (206) 543-0811 Husky Coaches Assistant Coach (Vault/Jumps):.......................... Pat Licari (9th year) Office Phone: (206) 685-7429 Head Coach Greg Metcalf -

Sprinters Falsify the Deliberate Practice Model of Expertise

You can’t teach speed: sprinters falsify the deliberate practice model of expertise Michael P. Lombardo1 and Robert O. Deaner2 1 Department of Biology, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI, USA 2 Department of Psychology, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI, USA ABSTRACT Many scientists agree that expertise requires both innate talent and proper training. Nevertheless, the highly influential deliberate practice model (DPM) of expertise holds that talent does not exist or makes a negligible contribution to performance. It predicts that initial performance will be unrelated to achieving expertise and that 10 years of deliberate practice is necessary. We tested these predictions in the domain of sprinting. In Studies 1 and 2 we reviewed biographies of 15 Olympic champions and the 20 fastest American men in U.S. history. In all documented cases, sprinters were exceptional prior to initiating training, and most reached world class status rapidly (Study 1 median D 3 years; Study 2 D 7.5). In Study 3 we surveyed U.S. national collegiate championships qualifiers in sprintersn ( D 20) and throwers (n D 44). Sprinters recalled being faster as youths than did throwers, whereas throwers recalled greater strength and throwing ability. Sprinters’ best performances in their first season of high school, generally the onset of formal training, were consistently faster than 95–99% of their peers. Collectively, these results falsify the DPM for sprinting. Because speed is foundational for many sports, they challenge the DPM generally. Subjects Evolutionary Studies, Psychiatry and Psychology Keywords Expertise, Deliberate practice model of expertise, Athletic performance, Sprinting, Evolutionary psychology, Display, Talent, Running, Sports, Training Submitted 11 April 2014 Accepted 2 June 2014 “I can make you faster, but I can’t make you fast.” Published 26 June 2014 Jerry Baltes, Head Coach, Grand Valley State University cross-country and track and Corresponding author field Michael P. -

Mc Ky Mc Ky He's the World's Fastest Man. but Can Tim

HE’S THE WORLD’S FASTEST MAN. BUT CAN TIM MONTGOMERY KEEP THE PAST BEHIND HIM? BY SHAUN ASSAEL 8 9 C M Y K C M Y K track and field N O W H E R E T O R U N TIM MONTGOMERY rocks back on ripped legs manager for the mill, won a Purple Heart as a junior record as a freshman. (It was rescinded three sheathed in red spandex, awaiting the starter’s sergeant in Vietnam. Problem was, the third of four weeks later when the track was found to be 3.7 cen- gun. The world’s fastest man glances to his imme- Montgomery children—all 125 pounds of him timeters too short). The next year, he hired an diate left at the world’s second-fastest man, stretched over a 5'10'' frame—didn’t have the agent and started racing for money in Europe. Maurice Greene. The promoters of the April 18 hands. His dropped passes frustrated the coaches at Montgomery never graduated from Blinn, but in Mount San Antonio College Relays in Walnut, Calif., Gaffney High, a football-obsessed school halfway 1996, he was recruited by D2 Norfolk State, where had planned to run them in separate heats. Then between Charlotte, N.C., and Greenville, S.C. When then-coach Steve Riddick honed his explosion by Montgomery’s agent called Greene’s people. The he fractured his arm as a junior, no one much cared making him run in deep water and practice stand- rivals hadn’t dueled in two years, he said.