No Tears Left to Cry”: Analyzing Space and Place of the Rock Concert Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Free Download

SISTER PUBLICATION Follow Us on WeChat Now Advertising Hotline 400 820 8428 AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2017 Chief Editor Frances Chen 陈满满 Production Manager Ivy Zhang 张怡然 Designers Aries Ji 季燕 Joan Dai 戴吉莹 Contributors Alyssa Marie Wieting, Betty Richardson, Celine Song, Dominic Ngai, Erica Martin, Frances Arnold, Kendra Perkins, Leonard Stanley, Manaz Javaid, Nate Balfanz, Theresa Kemp, Trevor Lai Operations Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路169号智造局2号楼305-306室 邮政编码:200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话:021-8023 2199 传真:021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 电话:020-8358 6125, 传真:020-8357 3859-800 Shenzhen 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 电话:0755-8623 3220, 传真:0755-8623 3219 Beijing 广告代理: 上海和舟广告有限公司 电话: 010-8447 7002 传真: 010-8447 6455 CEO Leo Zhou 周立浩 Sales Manager Doris Dong 董雯 BD Manager Tina Zhou 周杨 Sales & Advertising Jessica Ying Linda Chen 陈璟琳 Celia Chen 陈琳 Chris Chen 陈熠辉 Nikki Tang 唐纳 Claire Li 李文婕 Jessie Zhu 朱丽萍 Head of Communication Ned Kelly BD & Marketing George Xu 徐林峰 Leah Li 李佳颖 Peggy Zhu 朱幸 Zoey Zha 查璇 Operations Manager Penny Li 李彦洁 HR/Admin Sharon Sun 孙咏超 Distribution Zac Wang 王蓉铮 General enquiries and switchboard (021) 8023 2199 [email protected] Editorial (021) 8023 2199*5802 [email protected] Distribution (021) 8023 2199*2802 [email protected] Marketing/Subscription (021) 8023 2199*2806 [email protected] Advertising (021) 8023 2199*7802 [email protected] online.thatsmags.com shanghai.urban-family.com Advertising Hotline: 400 820 8428 城市家 出版发行:云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 -

Ebook Download Arlen and Harburgs Over the Rainbow 1St Edition

ARLEN AND HARBURGS OVER THE RAINBOW 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Walter Frisch | 9780190467340 | | | | | Arlen and Harburgs Over the Rainbow 1st edition PDF Book The parched, mysterious deserts of the world are the landscapes for this alphabet array of plants, animals, and phenomena. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Archived from the original on September 27, Any Condition Any Condition. American singer Ariana Grande released a version of the song on June 6, , to raise money at her benefit concert One Love Manchester after 22 people were killed in the Manchester Arena bombing at Grande's concert on May 22, User icon An illustration of a person's head and chest. Retrieved May 21, Digitized at 78 revolutions per minute. The winner of a Grammy Award, Collins' glorious voice is one of the most admired of the 20th and 21st centuries. The EP debuted at number four on the Billboard with 54, album-equivalent units , of which 50, were pure album sales. About this Item: Alfred Music, Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Osborn rated it liked it Dec 23, To ask other readers questions about Over the Rainbow , please sign up. Customer service is our top priority!. About this Item: HarperCollins Publishers. More information about this seller Contact this seller 6. Discography Great Balls of Fire! About this Item: Harper Collins, Meet Me in St. Retrieved June 6, Retrieved June 7, Uploaded by jakej on September 9, Seller Inventory X Michelle marked it as to-read Apr 08, Discography Performances Songs Awards and honors. -

Broadcast and on Demand Bulletin Issue Number 331 19/06/17

Issue 331 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 19 June 2017 Issue number 331 19 June 2017 Issue 331 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 19 June 2017 Contents Introduction 3 Broadcast Standards cases In Breach Drivetime Gravity FM, 27 March 2017, 15:00 6 Ramsay’s Hotel Hell Channel 4, 28 April 2017, 11.00 8 Fuck That’s Delicious Viceland, 26 February 2017, 13:00 10 Sikh Channel News Sikh Channel, 18 February 2017, 11:00 13 Shaun Tilley featuring 70s, 80s and 90s Heaven Cheesy FM, 9 February 2017, 18:26 17 Martin Lowes Capital FM North East, 27 March 2017, 17:30 19 Sam Rocks Rugby Sam FM (Bristol), 26 February 2017, 12:00 22 Jail Chittian Akaal Channel, 14 November 2016, 21:04 Health Show Akaal Channel, 14 November 2016, 21:38 25 Tour Down Under Bike, 21 January 2017, 15:00 31 Broadcast Licence Conditions cases In Breach Provision of information Channel i, 1 February 2017, 09:30 35 Providing a service in accordance with ‘Format’ Isles FM, 19 January 2017 to present 37 Issue 331 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 19 June 2017 Broadcast Fairness and Privacy cases Upheld Complaint by Mr John Shedden Party Political Broadcast by the Scottish National Party, BBC1 Scotland, 12 October 2016 39 Tables of cases Investigations Not in Breach 44 Complaints assessed, not investigated 45 Complaints outside of remit 54 Complaints about the BBC, not assessed 56 Investigations List 59 Issue 331 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 19 June 2017 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content to secure the standards objectives1. -

Shore 1Sts Vs High

The Shore Weekly Record Friday, 1 March 2019 Volume LXXX Term 1 Week 5 Headmaster’s Assembly Address verbal vilification and physical assault he would Number 42 face. Rickey knew that he needed a man with Some 40 years ago there was a comic radio wonderful skills and superhuman self-control and programme called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the he was sure Jackie, a man of deep faith, could do it. Galaxy which morphed into a book and a TV Jackie married his long-term sweetheart in series. Famously, at the end of the show the February 1946, then played the season with the answer to the meaning of life was stated: 42. Dodgers minor league franchise the Montreal Despite that, there is a real Number 42 which Royals. But the Dodgers announced on April 10th teaches us a great deal about the meaning of a well 1947 they had bought his contract, and the next day lived life; what a good man looks like. No major he walked out to play against the Yankees, in the league baseball player can wear the number 42. It pivotal role of first baseman. Twelve days later has been fully retired in tribute to the great they played the Phillies, whose manager organised Brooklyn Dodgers player Jackie Robinson. This the most despicable verbal and physical year on 31 January marks the 100th anniversary of intimidation. Every vile racist slur was used. his birth. History will always honour him as the Writing later Robinson wrote, “Starting to the plate man who broke the colour barrier in major league in the first inning, I could scarcely believe my baseball. -

Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18

PLANNING AND MANCHESTER MANAGEMENT, GEOGRAPHY ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHITECTURE INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP SCHOOL SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION AND LEISURE OF LAW SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 COURSES 2020 COURSES 2020 www.manchester.ac.uk/study-geography www.manchester.ac.uk/pem www.manchester.ac.uk/msa www.manchester.ac.uk/mie www.manchester.ac.uk/mll www.manchester.ac.uk www.manchester.ac.uk CHOOSE HY STUDY MANAGEMENT, MANCHESTER LEADERSHIPW AND LEISURE AT MANCHESTER? At Manchester, you’ll experience an education and environment that sets CONTENTS you on the right path to a professionally rewarding and personally fulfilling future. Choose Manchester and we’ll help you make your mark. Choose Manchester 2-3 Kai’s Manchester 4-5 Stellify 6-7 What the City has to offer 8-9 Applied Study Periods 10-11 Gain over 500 hours of industry experience through work-based placements Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18 Tailor your degree with options in sport, tourism and events management Broaden your horizons by gaining experience through UK-based or international work placements Develop skills valued within the global leisure industry, including learning a language via your free choice modules CHOOSE MANCHESTER 3 AFFLECK’S PALACE KAI’S Affleck’s is an iconic shopping emporium filled with unique independent traders selling everything from clothes, to records, to Pokémon cards! MANCHESTER It’s a truly fantastic environment with lots of interesting stuff, even to just window shop or get a coffee. -

Issue 37 | Apr 2018 Comedy, Literature & Film in Stroud

AN INDEPENDENT, FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC, ART, THEATRE, ISSUE 37 | APR 2018 COMEDY, LITERATURE & FILM IN STROUD. WWW.GOODONPAPER.INFO ISSUE #37 Inside: Annual Site Festival: Record Festival Moomins & Store Day Guide The Comet 2018 + The Clay Loft | Mark Huband | Bandit | Film Posters Reinterpreted Cover image by Joe Magee Joe image by Cover #37 | Apr 2018 EDITOR Advertising/Editorial/Listings: Editor’s Note Alex Hobbis [email protected] DESIGNER Artwork and Design Welcome To The Thirty Seventh Issue Of Good On Adam Hinks [email protected] Paper – Your Free Monthly Guide To Music Concerts, Art Exhibitions, Theatre Productions, Comedy Shows, ONLINE FACEBOOK TWITTER Film Screenings And Literature Events In Stroud… goodonpaper.info /GoodOnPaperStroud @GoodOnPaper_ Well Happy Birthday to us…Good On Paper is three! And we’ve gone a bit bumper. 32 PRINTED BY: pages this month – the most pages we have ever printed in one issue. All for you. To read. Then maybe recycle. Or use as kindling (these vegetable inks burn remarkably well). Tewkesbury Printing Company With it being our anniversary issue we’ve made a few design changes – specifically to the universal font and also to the front cover. For the next year we will be inviting some of our favourite local artists to design the front cover image – simply asking them to supply a piece of new work which might relate to one of the articles featured in that particular SPONSORED BY: issue. This month we asked our friend the award winning film maker and illustrator Joe Magee... Well that’s it for now, hope you enjoy this bigger issue of Good On Paper. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Thebestway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE

THE LAUNCH ISSUE T.O.W.I.E TO MK ONLY THE BEST WE LET MARK WRIGHT WE TRAVEL TO CHELSEA AND JAMESIII.V. ARGENT MMXIIIAND TALK BUSINESS LOOSE IN MILTON KEYNES WITH REFORMED PLAYBOY CALUM BEST BAG THAT JOB THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO HOT HATCH WALKING AWAY WITH WE GET HOT AND EXCITED THE JOB OFFER OVER THE LATEST HATCHES RELEASED THIS SUMMER LOOKING HOT GET THE STUNNING LOOKS ONE TOO MANY OF CARA DEVEVINGNE DO YOU KNOW WHEN IN FIVE SIMPLE STEPS ENOUGH IS ENOUGH? THEBESTway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE CONTENTS DOING IT THE WRIGHT WAY - THE TRENDLIFE LAUNCH PARTY The Only Way To launch TrendLife Magazine saw Essex boys Mark Wright and James ‘Arg’ Argent join us at Wonderworld in Milton Keynes alongside others including Corrie’s Michelle Keegen. Take a butchers at page 59 me old china. 14 MAIN FEATURES CALUM BEST ON CALUM BEST We sit down with Calum Best at 7 - 9 Chelsea’s Broadway House to discuss his new look on life, business and of course, the ladies. 12 MUST HAVES FOR SUMMER Get your credit card at the ready as 12 we give you ‘His and Hers’ essentials for this summer. You can thank us later. NEVER MIND THE SMALLCOCK Ladies, you have all been there and if 18 you have not, you will. What do you do when you are confronted with the ultimate let down? Fight or flight? #TRENDLIFEAWARDS REGISTER TODAY FOR THE EVENT OF 2013 WHATS NEW FIFA 14 PREVIEW | 35 No official release date. -

Download Booklet

Love Lives Beyond the Tomb Through These Pale Cold Days Op. 46 Songs and Song Cycles Song Cycle for Tenor, Viola and Piano IAN VENABLES t The Send-Off (Owen) [5.33] y Procrastination (St. Vincent Morris) [4.27] u Through these pale cold days (Rosenberg) [5.22] i Suicide in the Trenches (Sassoon) [2.38] Six Songs for Soprano and Piano o If You Forget (Studdert Kennedy) [4.29] 1 The Way Through Op. 33 No. 1 (Andrews) [3.14] Total timings: [78.42] 2 Aurelia Op. 37 No. 3 (Nichols) [3.19] 3 Chamber Music III Op. 41 No. 6 (Joyce) [4.49] 4 Love lives beyond the tomb Op. 37 No. 1 (Clare) [4.21] MARY BEVAN SOPRANO • ALLAN CLAYTON TENOR 5 Op. 33 No. 2 (Thomas) [5.44] It Rains CARDUCCI STRING QUARTET 6 I caught the changes of the year Op. 45 No. 1 (Drinkwater) [3.53] MATTHEW DENTON VIOLIN • MICHELLE FLEMING VIOLIN EOIN SCHMIDT-MARTIN VIOLA Remember This Op. 40 (Motion) EMMA DENTON CELLO Cantata for Soprano, Tenor, String Quartet and Piano GRAHAM J. LLOYD PIANO 7 Think of the failing body [3.35] www.signumrecords.com 8 In the swirl of its pool [2.40] 9 Think of the flower-lit coffin [4.35] 0 In the grip of their season [3.32] The songs and song cycles on this disc represent and highly acclaimed Requiem – Ian Venables q Think of the standard and its blaze [4.27] the most recent works written by a composer, has written over eighty works in this genre; w On the crest of their Downs [2.42] who has been described by Robert Matthew- his eight substantial song-cycles – many e Think of the buried body laid [4.58] Walker in the magazine Musical Opinion as of which include a string quartet or solo r In the eyes of our minds [4.20] ‘Britain’s finest composer of art songs’. -

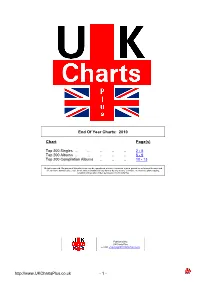

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

Vmas” Airing Live on Monday, August 20 at 9:00 PM ET/PT

Ariana Grande, Shawn Mendes and Logic with Ryan Tedder Set to Perform at the 2018 “VMAs” Airing Live on Monday, August 20 at 9:00 PM ET/PT August 2, 2018 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Aug. 2, 2018-- MTV today announced that Ariana Grande, Shawn Mendes and Logic with Ryan Tedder will take the stage at the 2018 “VMAs.” Grande will perform her smash hit single “God is a Woman” from her forthcoming album “Sweetener,” while Mendes will deliver his chart-topping song “In My Blood,” and Logic will perform his new single, “One Day,” featuring Ryan Tedder of OneRepublic, for the first time. As previously announced, Jennifer Lopez will be honored with the “Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award.” She is also set to perform at this year’s show for the first time since 2001. The “VMAs” will air live from Radio City Music Hall on Monday, August 20 at 9:00 p.m. ET/PT across MTV's global network of channels in more than 180 countries and territories, reaching more than half a billion households around the world. The full list of nominees for the 2018 “VMAs” is available here. Additional performers will be announced at a later date. Multiplatinum, record-breaking superstar Ariana Grande has delivered three platinum-selling albums and surpassed 18 billion streams, in addition to nabbing four Grammy Award nominations and landing eight hits in the Top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. With the release of “No Tears Left To Cry” she became the first artist in music history to see the lead single from her first four albums debut on the Top 10 on Billboard Hot 100.