Quasicrystalline Three-Dimensional Foams Arxiv:1610.09286V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robust Classification Method for Underwater Targets Using the Chaotic Features of the Flow Field

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Robust Classification Method for Underwater Targets Using the Chaotic Features of the Flow Field Xinghua Lin 1, Jianguo Wu 1,* and Qing Qin 2 1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin 300401, China; [email protected] 2 China Automotive Technology and Research Center Co., Ltd, Tianjin 300300, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 10 February 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: Fish can sense their surrounding environment by their lateral line system (LLS). In order to understand the extent to which information can be derived via LLS and to improve the adaptive ability of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), a novel strategy is presented, which directly uses the information of the flow field to distinguish the object obstacle. The flow fields around different targets are obtained by the numerical method, and the pressure signal on the virtual lateral line is studied based on the chaos theory and fast Fourier transform (FFT). The compounded parametric features, including the chaotic features (CF) and the power spectrum density (PSD), which is named CF-PSD, are used to recognize the kinds of obstacles. During the research of CF, the largest Lyapunov exponent (LLE), saturated correlation dimension (SCD), and Kolmogorov entropy (KE) are taken into account, and PSD features include the number, amplitude, and position of wave crests. A two-step support vector machine (SVM) is built and used to classify the shapes and incidence angles based on the CF-PSD. It is demonstrated that the flow fields around triangular and square targets are chaotic systems, and the new findings indicate that the object obstacle can be recognized directly based on the information of the flow field, and the consideration of a parametric feature extraction method (CF-PSD) results in considerably higher classification success. -

Engineering the Quantum Foam

Engineering the Quantum Foam Reginald T. Cahill School of Chemistry, Physics and Earth Sciences, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide 5001, Australia [email protected] _____________________________________________________ ABSTRACT In 1990 Alcubierre, within the General Relativity model for space-time, proposed a scenario for ‘warp drive’ faster than light travel, in which objects would achieve such speeds by actually being stationary within a bubble of space which itself was moving through space, the idea being that the speed of the bubble was not itself limited by the speed of light. However that scenario required exotic matter to stabilise the boundary of the bubble. Here that proposal is re-examined within the context of the new modelling of space in which space is a quantum system, viz a quantum foam, with on-going classicalisation. This model has lead to the resolution of a number of longstanding problems, including a dynamical explanation for the so-called `dark matter’ effect. It has also given the first evidence of quantum gravity effects, as experimental data has shown that a new dimensionless constant characterising the self-interaction of space is the fine structure constant. The studies here begin the task of examining to what extent the new spatial self-interaction dynamics can play a role in stabilising the boundary without exotic matter, and whether the boundary stabilisation dynamics can be engineered; this would amount to quantum gravity engineering. 1 Introduction The modelling of space within physics has been an enormously challenging task dating back in the modern era to Galileo, mainly because it has proven very difficult, both conceptually and experimentally, to get a ‘handle’ on the phenomenon of space. -

Hyperbolic Prism, Poincaré Disc, and Foams

Hyperbolic Prism, Poincaré Disc, and Foams 1 1 Alberto Tufaile , Adriana Pedrosa Biscaia Tufaile 1 Soft Matter Laboratory, Escola de Artes, Ciências e Humanidades, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. The hyperbolic prism is a transparent optical element with spherical polished surfaces that refracts and reflects the light, acting as an optical element of foam. Using the hyperbolic prism we can face the question: is there any self-similarity in foams due to light scattering? In order to answer this question, we have constructed two optical elements: the hyperbolic kaleidoscope and the hyperbolic prism. The key feature of the light scattering in such elements is that this phenomenon is chaotic. The propagation of light in foams creates patterns which are generated due to the reflection and refraction of light. One of these patterns is observed by the formation of multiple mirror images inside liquid bridges in a layer of bubbles in a Hele-Shaw cell. We have observed the existence of these patterns in foams and their relation with hyperbolic geometry using the Poincaré disc model. The images obtained from the experiment in foams are compared to the case of hyperbolic optical elements, and there is a fractal dimension associated with the light scattering which creates self-similar patterns Keywords: Hyperbolic Prism, Poincaré Disc, Foams, Kaleidoscope. 1 Introduction Physically based visualization of foams improves our knowledge of optical systems. As long as the light transport mechanisms for light scattering in foams are understood, some interesting patterns observed can be connected with some concepts involving hyperbolic geometry, and this study involves mainly the classical scattering of light in foams and geometrical optics. -

Modelling and Simulation of Acoustic Absorption of Open Cell Metal Foams

Modelling and Simulation of Acoustic Absorption of Open Cell Metal Foams Claudia Lautensack, Matthias Kabel Fraunhofer ITWM, Kaiserslautern Abstract We analyse the microstructure of an open nickel-chrome foam using computed tomography. The foam sample is modelled by a random Laguerre tessellation, i.e. a weighted Voronoi tessellation, which is fitted to the original structure by means of geometric characteristics estimated from the CT image. Using the Allard-Johnson model we simulate the acoustic absorption of the real foam and the model. Finally, simulations in models with a larger variation of the cell sizes yield first results for the dependence of acoustic properties on the geometric structure of open cell foams. 1. Introduction Open cell metal foams are versatile materials which are used in many application areas, e.g. as heat exchangers, catalysts or sound absorbers. The physical properties of a foam are highly affected by its microstructure, for instance the porosity or the specific surface area of the material or the size and shape of the foam cells. An understanding of the change of the foam’s properties with altering microstructure is crucial for the optimisation of foams for certain applications. Foam models from stochastic geometry are powerful tools for the investigation of these relations. Edge systems of random tessellations are often used as models for open foams. Geometric characteristics which are estimated from tomographic images of the foams are used for fitting the models to real data. Realisations of foams with slightly modified microstructure can then be generated by changing the model parameters. Numerical simulations in these virtual foam samples allow for an investigation of relations between the geometric structure of a material and its physical properties. -

Crystalclear® Foam-B-Gone

® Airmax® Inc. CrystalClear Foam-B-Gone 15425 Chets Way, Armada, MI 48005 Phone: 866-424-7629 Safety Data Sheet www.airmaxeco.com SECTION 1: IDENTIFICATION Product Trade Name: CrystalClear® Foam-B-Gone Date: 09-15-15 Name and/or Family or Description: Organic-inorganic mixtures Chemical Name: Anti-Foam Emulsion Chemical Formula: N/A CAS No.: N/A DOT Proper Shipping Name: Chemicals Not Otherwise Indexed (NOI) Non-Hazardous DOT Hazard Class: Not Regulated - None DOT Label: None MANUFACTURER/IMPORTER/SUPPLIER/DISTRIBUTOR INFORMATION: COMPANY NAME: Airmax®, Inc. COMPANY ADDRESS: P.O. Box 38, Romeo, Michigan 48065 COMPANY TELEPHONE: Office hours (Mon - Fri) 9:00 am to 5:00 pm (866) 424-7629 COMPANY CONTACT NAME: Main Office EMERGENCY PHONE NUMBER: Poison Control 800-222-1222 SECTION 2: HAZARD(S) IDENTIFICATION OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE LIMITS Ingredient Percent CAS No. PEL (Units) Hazard N/A 100% N/A N/E N/A *This product contains no hazardous ingredients according to manufacturer. *No components, present in excess of 0.1% by weight are listed as carcinogens by IARC, NTP, or OSHA *.A.R.A Information - SARA Applies – No reportable quantity to 312 / 313 / 372 SECTION 3: COMPOSITION/ INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS INGREDIENT NAME CAS NUMBER WEIGHT % Propylene Glycol 57-55-6 1 - <3 Other components below reportable levels 90 - 100 *Designates that a specific chemical identity and/or percentage of composition has been withheld as a trade secret. SECTION 4: FIRST AID MEASURES INHALATION: Promptly remove to fresh air. Call a physician if symptoms develop or persist. SKIN: Wash skin with plenty of soap and water. -

Low Rattling: a Predictive Principle for Self-Organization in Active Collectives

Low rattling: a predictive principle for self-organization in active collectives Pavel Chvykov,1 Thomas A. Berrueta,2 Akash Vardhan,3 William Savoie,3 Alexander Samland,2 Todd D. Murphey,2 3 3 3;4 Kurt Wiesenfeld, Daniel I. Goldman, Jeremy L. England ∗ 1Physics of Living Systems, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA 3School of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia 30332, USA 4GlaxoSmithKline AI/ML, 200 Cambridgepark Drive, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140, USA ∗To whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: [email protected] Self-organization is frequently observed in active collectives, from ant rafts to molecular motor assemblies. General principles describing self-organization away from equilibrium have been challenging to iden- tify. We offer a unifying framework that models the behavior of com- plex systems as largely random, while capturing their configuration- dependent response to external forcing. This allows derivation of a Boltzmann-like principle for understanding and manipulating driven self-organization. We validate our predictions experimentally in shape- changing robotic active matter, and outline a methodology for con- trolling collective behavior. Our findings highlight how emergent or- arXiv:2101.00683v1 [cond-mat.stat-mech] 3 Jan 2021 der depends sensitively on the matching between external patterns of forcing and internal dynamical response properties, pointing towards future approaches for design and control of active particle mixtures and metamaterials. 1 ACCEPTED VERSION: This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here by permission of the AAAS for personal use, not for redistribution. The definitive version was published in Science, (2021-01-01), doi: 10.1126/science.abc6182 Self-organization in nature is surprising because getting a large group of separate particles to act in an organized way is often difficult. -

Fibonacci Numbers and the Golden Ratio in Biology, Physics, Astrophysics, Chemistry and Technology: a Non-Exhaustive Review

Fibonacci Numbers and the Golden Ratio in Biology, Physics, Astrophysics, Chemistry and Technology: A Non-Exhaustive Review Vladimir Pletser Technology and Engineering Center for Space Utilization, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; [email protected] Abstract Fibonacci numbers and the golden ratio can be found in nearly all domains of Science, appearing when self-organization processes are at play and/or expressing minimum energy configurations. Several non-exhaustive examples are given in biology (natural and artificial phyllotaxis, genetic code and DNA), physics (hydrogen bonds, chaos, superconductivity), astrophysics (pulsating stars, black holes), chemistry (quasicrystals, protein AB models), and technology (tribology, resistors, quantum computing, quantum phase transitions, photonics). Keywords Fibonacci numbers; Golden ratio; Phyllotaxis; DNA; Hydrogen bonds; Chaos; Superconductivity; Pulsating stars; Black holes; Quasicrystals; Protein AB models; Tribology; Resistors; Quantum computing; Quantum phase transitions; Photonics 1. Introduction Fibonacci numbers with 1 and 1 and the golden ratio φlim → √ 1.618 … can be found in nearly all domains of Science appearing when self-organization processes are at play and/or expressing minimum energy configurations. Several, but by far non- exhaustive, examples are given in biology, physics, astrophysics, chemistry and technology. 2. Biology 2.1 Natural and artificial phyllotaxis Several authors (see e.g. Onderdonk, 1970; Mitchison, 1977, and references therein) described the phyllotaxis arrangement of leaves on plant stems in such a way that the overall vertical configuration of leaves is optimized to receive rain water, sunshine and air, according to a golden angle function of Fibonacci numbers. However, this view is not uniformly accepted (see Coxeter, 1961). N. Rivier and his collaborators (2016) modelized natural phyllotaxis by the tiling by Voronoi cells of spiral lattices formed by points placed regularly on a generative spiral. -

Ttu Hcc001 000095.Pdf (12.16Mb)

) I " , • ' I • DEPARTMENT OF HOUSEHOLD SCIENCE Illinois State Normal University , NormaL Illinois ILLINOIS STATE NORMAL UNIVERSITY-HOUSEHOt:'t> SCIENCE DEPARTMENT INDEX TO INVALID COOKERY RECIPES BEVERAGES PAGE BREDS- Continued PAGE Albumen, Plain........... .................. ........ 12 Toast.......................... .. .................. .............. 2 Albumenized Lemon juice . ......... ................ ..... 12 Creamy.......... ...... ............ .. .... ........ .. ...... 2 lVlilk . .. ....... ........................ ..... .... 12 Cracker......... ......... ............... ... .. .. .......... 2 Orange juice .......... ................... 12 Dry .......................... .... ....... ...... ........... 2 \Vater .............. .......... ..... ............ 12 1\'lilk ....................................... .. .... ......... 2 Broth, Eg ....................................... ........ .. .... 13 Sa uce for, Method I. .................. ....... .. ..... 2 Cream, To serv a cup........ ............ .................. 7 Method II................ ... .. ... ...... 2 Chocolate. ......... ........ ......................... ........ .... 1 Method III....... ........... ..... ....... 2 Coco ........ .................. ........ ....... .. .......... .. .. .... 1 \'-Ta ter ...... ........................ ....................... 2 Coffee, Boild. ............... ...... ...... ...... ...... ........... 1 Z\\-i eback......... .. ...... ................ ..................... 3 Cereal. ... .............. .. .. .. ......... .. .............. -

Liquid Crystal Foam

Liquid crystal foam C. Cruza;b, M. H. Godinhoc, A. J. Ferreirac, P. S. Kulkarnid;e, C. A. M. Afonsoe and P. I. C. Teixeiraf;g aCentro de Fis´ıcada Mat´eriaCondensada, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal bDepartamento de F´ısica,Instituto Superior T´ecnico, Universidade T´ecnicade Lisboa, Portugal cDepartamento de Ci^enciados Materiais and CENIMAT/I3N, Faculdade de Ci^enciase Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal dREQUIMTE, Departamento de Qu´ımica, Faculdade de Ci^enciase Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal eCQFM, Departamento de Engenharia Qu´ımicae Biol´ogica, Instituto Superior T´ecnico,Universidade T´ecnicade Lisboa, Portugal f Instituto Superior de Engenharia de Lisboa, Portugal gCentro de F´ısicaTe´oricae Computacional, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Motivation Room-temperature ionic liquids are salts whose melting point is below 100◦C. Typically they are made up of large polyatomic ions. They exhibit interesting properties leading to applications: Green solvents; conductive matrices for electrochemical devices. By careful molecular design they can be made to exhibit lamellar or columnar liquid crystalline (LC) phases at or near room temperature. These phases have enhanced ionic conductivity. C. Cruza;b, M. H. Godinhoc, A. J. Ferreirac, P. S. Kulkarnid;e, C. A. M. AfonsoLiquide and crystal P. I. foam C. Teixeiraf;g Sample preparation Solutions of n-alkylimidazolium salts in acetone were prepared at room temperature followed by stirring to allow homogenisation. Films were cast and sheared simultaneously by moving a casting knife over a glass substrate at v = 5 mm/s. Film thickness after solvent evaporation was 10{20 µm. Films were then observed by polarised optical microscopy. -

The Mathematics of Foam

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Mathematical Institute Eprints Archive The Mathematics of Foam Christopher James William Breward St Anne's College University of Oxford A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 1999 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is a foam? . 1 1.2 How do foams form? . 5 1.3 Why does a foam persist after it has been formed? . 5 1.3.1 Surfactants . 5 1.3.2 How does a surface tension gradient affect a liquid flow? . 6 1.3.3 Volatile Components . 7 1.4 What happens to lamellae when they become thin? . 7 1.5 How does a lamella rupture? . 7 1.6 How are foams destroyed in industrial situations where they are not wanted? 8 1.7 Background material . 8 1.8 Thesis plan . 12 1.9 Statement of Originality . 13 2 Modelling of liquids, surfactants and volatile systems 14 2.1 Liquid modelling . 15 2.1.1 Field Equations . 15 2.1.2 Boundary conditions . 15 2.2 Surfactants . 16 2.2.1 Effect of surfactant on the surface tension . 18 2.3 Volatile and Inert systems . 19 2.3.1 Volatile component at the free surface . 19 2.3.2 Model for evaporation . 20 2.4 Summary . 20 3 Modelling expanding free surfaces 22 3.1 Introduction . 22 3.2 The overflowing cylinder . 22 3.3 Previous work . 24 i 3.3.1 Experimental observations . 25 3.3.2 Plan . 31 3.4 Model formulation: velocity distribution . 31 3.4.1 Typical non-dimensional parameter sizes based on flow at depth . -

Crystal Foam SDS.Pdf

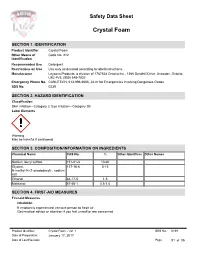

Safety Data Sheet Crystal Foam SECTION 1. IDENTIFICATION Product Identifier Crystal Foam Other Means of Code No. 212 Identification Recommended Use Detergent. Restrictions on Use Use only as directed according to label instructions. Manufacturer Leysons Products, a division of 1787528 Ontario Inc., 1366 Sandhill Drive, Ancaster, Ontario, L9G 4V5, (905) 648-7832 Emergency Phone No. CANUTECH, 613-996-6666, 24-hr for Emergencies involving Dangerous Goods SDS No. 0239 SECTION 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION Classification Skin irritation - Category 2; Eye irritation - Category 2B Label Elements Warning May be harmful if swallowed. SECTION 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Chemical Name CAS No. % Other Identifiers Other Names Sodium lauryl sulfate 151-21-3 10-30 Glycine, 137-16-6 5-15 N-methyl-N-(1-oxododecyl)-, sodium salt Ethanol 64-17-5 1-5 Methanol 67-56-1 0.5-1.0 SECTION 4. FIRST-AID MEASURES First-aid Measures Inhalation If irritation is experienced, remove person to fresh air. Get medical advice or attention if you feel unwell or are concerned. Skin Contact Product Identifier: Crystal Foam - Ver. 1 SDS No.: 0239 Date of Preparation: January 17, 2017 Date of Last Revision: Page 01 of 06 Skin Contact In case of contact, immediately flush skin with plenty of water. Call a physician if irritation develops or persists. Eye Contact Immediately rinse the contaminated eye(s) with lukewarm, gently flowing water for 15-20 minutes, while holding the eyelid(s) open. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. If eye irritation persists, get medical advice or attention. Ingestion In case of ingestion, call a doctor or anti-poison Centre. -

Math in Nature.Key

Mathematics in Nature: Bees, Honeycombs Bubbles, and Mud Cracks Jonna Massaroni, Catherine Kirk Robins, Amanda MacIntosh & Amina Eladdadi, Department of Mathematics Bees & Honeycombs Bubbles Mud Cracks The most fascinating application of hexagons is the Look virtually anywhere, and you can find bubbles. As the Earth’s surface loses water not only are mud honeycomb. It is common knowledge that circular cells Whether they’re from the soap in your kitchen sink or cracks formed, but polygons as well. These polygons create wasted space, whereas hexagonal cells, such as from the hot gasses vented from the ocean floor, all create a form of repeating symmetry throughout the the ones that can be found in honeycombs, are more bubbles are subjected to the same mathematical rules dried mud puddles. As the mud loses water, this causes efficient. In fact, if one places six regular hexagons in a and concepts. Bubbles are considered to be what are it to shrink and separate. The drying mud becomes ring with each pair sharing one common side, a free called, “minimal surface structures.” Essentially, bubbles brittle and not only forms into its shapes of polygons but seventh hexagon appears in the center. This seven- form a spherical shape that employs the least amount of is separated by vertical cracks. These polygons are hexagon honeycomb arrangement maximizes the area surface area needed to enclose any given volume of air made up of straight lines creating a path or circuit. This enclosed in the honeycomb while minimizing the or gas. They remain spherical because there is an equal symmetry formed by mud puddles is also formed perimeter.