Is India's Ministry of Coal Effective in Supporting Coal Production?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINISTRY of COAL and MINES DEMAND NO. 10 Department of Coal

Notes on Demands for Grants, 2004-2005 25 MINISTRY OF COAL AND MINES DEMAND NO. 10 Department of Coal A. The Budget allocations, net of recoveries, are given below: (In crores of Rupees) Budget 2003-2004 Revised 2003-2004 Budget 2004-2005 Major Head Plan Non-Plan Total Plan Non-Plan Total Plan Non-Plan Total Revenue 285.90 152.00 437.90 150.00 151.66 301.66 119.82 200.00 319.82 Capital ... ... ... ... ... ... 103.50 ... 103.50 Total 285.90 152.00 437.90 150.00 151.66 301.66 223.32 200.00 423.32 1. Secretariat-Economic Services 3451 ... 6.28 6.28 ... 6.01 6.01 4.50 6.77 11.27 Labour and Employment Coal Mines Labour Welfare 2. Contribution to the Coal Mines Pension Scheme/Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme 2230 ... 28.23 28.23 ... 28.23 28.23 ... 31.46 31.46 Coal and Lignite 3. Conservation and Safety in Coal Mines (Met out of cess collections) 2803 ... 64.00 64.00 ... 64.00 64.00 ... 90.00 90.00 4. Development of Transportation infrastructure in Coal field areas (Met out of cess collections) 2803 ... 50.94 50.94 ... 50.94 50.94 ... 69.12 69.12 5. Scheme of grant-in-aid to PSUs for implementation of VRS 2803 138.44 ... 138.44 ... ... ... ... ... ... 6. Loan to PSUs for implementation of VRS 6803 ... ... ... ... ... ... 103.50 ... 103.50 7. Research & Development Programme 2803 22.48 ... 22.48 10.04 ... 10.04 9.88 ... 9.88 8. Regional Exploration 2803 56.10 ... 56.10 85.18 .. -

List of Council of Ministers

LIST OF COUNCIL OF MINISTERS Shri Narendra Modi Prime Minister and also in-charge of: Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Department of Atomic Energy; Department of Space; and All important policy issues; and All other portfolios not allocated to any Minister. CABINET MINISTERS 1. Shri Raj Nath Singh Minister of Home Affairs. 2. Smt. Sushma Swaraj Minister of External Affairs. 3. Shri Arun Jaitley Minister of Finance; and Minister of Corporate Affairs. 4. Shri Nitin Jairam Gadkari Minister of Road Transport and Highways; Minister of Shipping; and Minister of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. 5. Shri Suresh Prabhu Minister of Commerce and Industry. 6. Shri D.V. Sadananda Gowda Minister of Statistics and Programme Implementation. 7. Sushri Uma Bharati Minister of Drinking Water and Sanitation. 8. Shri Ramvilas Paswan Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. 9. Smt. Maneka Sanjay Gandhi Minister of Women and Child Development. 10. Shri Ananthkumar Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers; and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. 11. Shri Ravi Shankar Prasad Minister of Law and Justice; and Minister of Electronics and Information Technology. Page 1 of 7 12. Shri Jagat Prakash Nadda Minister of Health and Family Welfare. 13. Shri Ashok Gajapathi Raju Minister of Civil Aviation. Pusapati 14. Shri Anant Geete Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises. 15. Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal Minister of Food Processing Industries. 16. Shri Narendra Singh Tomar Minister of Rural Development; Minister of Panchayati Raj; and Minister of Mines. 17. Shri Chaudhary Birender Minister of Steel. Singh 18. Shri Jual Oram Minister of Tribal Affairs. -

First Report of Group of Ministers to Consider Measures That Can Be Taken by the Government to Tackle Corruption

FIRST REPORT OF GROUP OF MINISTERS TO CONSIDER MEASURES THAT CAN BE TAKEN BY THE GOVERNMENT TO TACKLE CORRUPTION. Department of Personnel and Training April 2011 1 FIRST REPORT OF GROUP OF MINISTERS TO CONSIDER MEASURES THAT CAN BE TAKEN BY THE GOVERNMENT TO TACKLE CORRUPTION. INTRODUCTION Government is committed towards zero tolerance against corruption and has taken several steps for anti corruption measures. Unfortunately, such interventions have been perceived to be ineffectual and there is cynicism on the subject. These are, in the words of second ARC report (January 2007) “seen as mere posturing without any real intention to bring the corrupt to book.” There have been allegations of corruption in many areas in recent times. In order to examine the entire issue, a Group of Ministers, with the following composition of members, was constituted by the Government on 6th January, 2011 with the approval of the Prime Minister to consider measures that can be taken by the Government to tackle corruption. (Annexure-I). (1) Shri Pranab Mukherjee, Minister of Finance, (2) Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries; (3) Shri A.K. Antony, Minister of Defence; (4) Shri P. Chidambaram, Minister of Home Affairs; (5) Km. Mamata Banerjee, Minister of Railways; (6) Shri M. Veerappa Moily, Minister of Law and Justice; 2 (7) Shri Kapil Sibal, Minister of Human Resource Development and Minister of Communications and Information Technology; and (8) Shri M.K. Alagiri, Minister of Chemicals and Fertilizers; and Special Invitee Shri V. Narayanasamy, Minister of State in the Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs; Minister of State in the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions and Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s Office. -

MONDAY, the 3RD AUGUST, 2009 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A.M.) @11-03 A.M

MONDAY, THE 3RD AUGUST, 2009 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) @11-03 a.m. 1. Obituary References The Chairman made references to the passing away of the following ex-Members— 1. Shri Syed Rahmat Ali; and 2. Shri Devendra Nath Dwivedi. The House observed silence, all Members standing, as a mark of respect to the memory of the departed. (The House adjourned at 11-05 a.m. and re-assembled at 12-00 Noon) 2. Starred Questions Answers to Starred Question Nos. 421 to 440 were laid on the Table. 3. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 3191 to 3345 were laid on the Table. 12-00 Noon. 4. Papers Laid on the Table Shri M. Veerappa Moily (Minister of Law and Justice) laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (a) Annual Report and Accounts of the Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary Studies (ICPS), New Delhi, for the year 2007-08, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. (b) Statement by Government accepting the above Report. (c) Statement giving reasons for the delay in laying the papers mentioned at (a) above. @ From 11-00 a.m. to 11-03 a.m. some points were raised. RAJYA SABHA Shri B.K. Handique (Minister of Mines and Minister of Development of North Eastern Region) laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (a) Eighteenth Annual Report and Accounts of the National Institute of Miners’ Health, Nagpur, for the year 2007-08, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. -

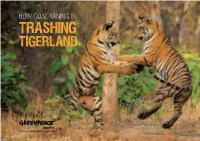

How Coal Mining Is Trashing Tigerland

Author Contact Ashish Fernandes Ashish Fernandes [email protected] Research coordination & North Karanpura case study Nandikesh Sivalingam Kanchi Kohli [email protected] Research Photo Editor Aishwarya Madineni, Vikal Samdariya, Arundhati Sudhanshu Malhotra Muthu and Preethi Herman Design GIS Analysis Aditi Bahri Ecoinformatics Lab, ATREE (Kiran M.C., Madhura Cover image Niphadkar, Aneesh A., Pranita Sambhus) © Harshad Barve / Greenpeace Acknowledgments Image Sudiep Shrivastava for detailed inputs on the Forests of Sanjay Dubri Tiger Hasdeo-Arand and Mandraigarh sections, Kishor Reserve near Singrauli coalfield Rithe for inputs on the Wardha and Kamptee © Dhritiman Mukherjee / Greenpeace sections, Bulu Imam and Justin Imam for their expertise on the North Karanpura section, Biswajit Printed on 100% recycled paper. Mohanty for feedback on the Talcher and Ib Valley sections and Belinda Wright for feedback on the Sohagpur and Singrauli sections. CONTENTS Executive Summary 01 9. Hasdeo-Arand (Chhattisgarh) 51 10. West Bokaro (Jharkhand) 55 Introduction 09 Central India,Tigers, Corridors and Coal 11. North Karanpura (Jharkhand) 60 How Coal is Trashing Tigerland 17 Case Study I 63 The North Karanpura Valley - On the edge Methodology 21 12. Wardha (Maharashtra) 00 Coalfield Analysis 25 13. Kamptee (Maharashtra) 00 1. Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 27 Case Study II 87 2. Sohagpur (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 33 Chandrapur’s tigers - Encircled by coal 3. Sonhat (Chhattisgarh) 35 4. Tatapani (Chhattisgarh) 37 Alternatives: Efficiency and Renewables 101 5. Auranga (Jharkhand) 39 References 109 6. Talcher (Odisha) 41 Glossary 7. Ib Valley (Odisha) 47 110 8. Mandraigarh (Chhattisgarh) 49 Endnotes 111 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As India’s national animal, the Royal Bengal Tiger Panthera tigris has ostensibly been a conservation priority for current and past governments. -

No 23011/1/2015-CPD Government of India Ministry of Coal Shastri

No 23011/1/2015-CPD Government of India Ministry of Coal Shastri Bhavan, New Delhi 110 001 Dated the 18th March, 2015 OFFICE MEMORANDUM Subject: Minutes of the Second meeting of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for proposed auction of coal linkages/LoAs through competitive bidding held on 09.03.2015. The undersigned is directed to forward herewith a minutes of the Second meeting of the Inter- Ministerial Committee for proposed auction of coal linkages/LoAs through competitive bidding held on 09.03.2015, under the Chairmanship of Shri A. K. Bhalla, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Coal at 3rd floor, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi. 12-:3.2015 (Pilli Ravi Kumar) Under Secretary to the Govt. of India Ph. No.23384285 1. Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, North Block, New Delhi 2. Secretary, Ministry of Power, Shram Shakti Bhawan, New Delhi (Att. Shri. A.K. Singh, Joint Secretary ) 3. Secretary, NITI Ayog, Yojana Bhawan, New Delhi (Att. Shri. Somit Dasgupta, Advisor ) 4. Chairman, Railway Board, Rail Bhawan, New Delhi(Att. Shri. Manoj Akhauri, EDTT/F ) 5. Secretary, Ministry of Steel, Udyog Bhawan, New Delhi(Att. Shri S. Abbasi, Joint Secretary) 6. Secretary, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Udyog Bhawan, New Delhi(Att. Shri Mohan Chutani, Eco Advisor) 7. Secretary, Ministry of Law and Justice, Department of Legal Affairs, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi (Att. Dr. R.S. Shrinet, ALA) 8. Secretary Department of Financial Services, Jeevan Deep Building New Delhi. 9. Chairman, Coal India Ltd. Kolkata(Att. Shri B.K. Saxena, Director (Marketing) ) 10. Chairman, SCCL, PB No. 18, Red Hills, Khairatabad, Hyderabad, AP(Att. -

Union Cabinet Minister, India.Pdf

India gk World gk Misc Q&A English IT Current Affairs TIH Uninon Cabinet Minister of India Sl No Portfolio Name Cabinet Minister 1 Prime Minister Minister of Atomic Energy Minister of Space Manmohan Singh Minister of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions Ministry of Planning 2 Minister of Finance P. Chidambaram 3 Minister of External Affairs Salman Khurshid 4 Minister of Home Affairs Sushil Kumar Shinde 5 Minister of Defence A. K. Antony 6 Minister of Agriculture Sharad Pawar Minister of Food Processing Industries 7 Minister of Communications and Information Technology Kapil Sibal Minister of Law and Justice 8 Minister of Human Resource Development Dr. Pallam Raju 9 Ministry of Mines Dinsha J. Patel 10 Minister of Civil Aviation Ajit Singh 11 Minister of Commerce and Industry Anand Sharma Minister of Textiles 12 Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas Veerappa Moily 13 Minister of Rural Development Jairam Ramesh 14 Minister of Culture Chandresh Kumari Katoch 15 Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation Ajay Maken 16 Minister of Water Resources Harish Rawat 17 Minister of Urban Development Kamal Nath Minister of Parliamentary Affairs 18 Minister of Overseas Indian Affairs Vayalar Ravi 19 Minister of Health and Family Welfare Ghulam Nabi Azad 20 Minister of Labour and Employment Mallikarjun Kharge 21 Minister of Road Transport and Highways Dr. C. P. Joshi Minister of Railway 22 Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises Praful Manoharbhai Patel 23 Minister of New and Renewable Energy Farooq Abdullah 24 Minister of Panchayati Raj Kishore Chandra Deo Minister of Tribal Affairs 25 Minister of Science and Technology Jaipal Reddy Minister of Earth Sciences 26 Ministry of Coal Prakash Jaiswal 27 Minister of Steel Beni Prasad Verma 28 Minister of Shipping G. -

70 POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 1947 to 2017, Independence to $2.5 Trillion

Gautam Chikermane POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 70 POLICIES THAT SHAPED INDIA 1947 to 2017, Independence to $2.5 Trillion Gautam Chikermane Foreword by Rakesh Mohan © 2018 by Observer Research Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. ISBN: 978-81-937564-8-5 Printed by: Mohit Enterprises CONTENTS Foreword by Rakesh Mohan vii Introduction x The First Decade Chapter 1: Controller of Capital Issues, 1947 1 Chapter 2: Minimum Wages Act, 1948 3 Chapter 3: Factories Act, 1948 5 Chapter 4: Development Finance Institutions, 1948 7 Chapter 5: Banking Regulation Act, 1949 9 Chapter 6: Planning Commission, 1950 11 Chapter 7: Finance Commissions, 1951 13 Chapter 8: Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951 15 Chapter 9: Indian Standards Institution (Certification Marks) Act, 1952 17 Chapter 10: Nationalisation of Air India, 1953 19 Chapter 11: State Bank of India Act, 1955 21 Chapter 12: Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, 1955 23 Chapter 13: Essential Commodities Act, 1955 25 Chapter 14: Industrial Policy Resolution, 1956 27 Chapter 15: Nationalisation of Life Insurance, 1956 29 The Second Decade Chapter 16: Institutes of Technology Act, 1961 33 Chapter 17: Food Corporation of India, 1965 35 Chapter 18: Agricultural Prices Commission, 1965 37 Chapter 19: Special Economic Zones, 1965 39 iv | 70 Policies that Shaped India The Third Decade Chapter 20: Public Provident Fund, 1968 43 Chapter 21: Nationalisation of Banks, 1969 45 Chapter -

Governance in Coal Mining: Issues and Challenges

The Energy and Resources Institute TERI-NFA Working Paper No. 9 Governance in Coal Mining: Issues and Challenges Arpita Asha Khanna August 2013 1 2 Acknowledgements This paper was written as part of a project ‘Analyzing Global, Regional and National Energy Governance Structures’ under the Program of Activities, Framework Agreement between the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), briefly referred to as the Norwegian Framework Agreement (NFA). We would like to thank the Norwegian MFA for their support. Corresponding Author, Arpita Asha Khanna, is an Associate Fellow at TERI, New Delhi. Email: [email protected] © TERI, 2013 Contacts The Energy and Resources Institute Darbari Seth Block India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road New Delhi 110 003 Tel: + 91 - 11- 24682100 / 41504900 3 Table of Content Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Overview of coal sector in India ..................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Industry organization ............................................................................................................... 7 1.2. Legal & regulatory framework ................................................................................................ 8 1.3. Institutional structure .............................................................................................................. -

Council of Ministers

COUNCILOFMINISTERS (1947-2015) NAMESANDPORTFOLIOSOFTHEMEMBERS OF THEUNIONCOUNCILOFMINISTERS (From15August1947to28August2015 ) LOKSABHASECRETARIAT NEWDELHI 2016 LARRDIS/REFERENCE 2016 First Edition : 1968 Second Edition : 1978 Third Edition : 1985 Reprint : 1987 Fourth Edition : 1990 Fifth Edition : 1997 Sixth Edition : 2004 Seventh Edition : 2011 Eighth Edition : 2016 Price : R 500.00 $ 7.50 £ 6.00 © 2016 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fifteenth Edition) and printed by Aegean Offset Printers, New Delhi. PREFACE ThisbrochureprovidesinformationonMembersoftheUnionCouncil ofMinistersandtheirportfoliossince15August1947.Thebrochurewas firstpublishedinMay1968andthepresentupdatededitionistheeighth oneintheseries,whichcontainsinformationfortheperiodfrom 15August1947to28August2015. InformationonthenumberofMinistersineachcategory,tenuresofall PrimeMinistersandthechangeseffectedintheUnionCouncilofMinisters fromtimetotimehasbeenincorporatedintheIntroduction. ThisbrochureisdividedintosevenParts.PartIdealswiththe PrimeMinisterssinceIndependence;PartIIcontainsinformationonthe MinisterialcareerofthosewhobecameDeputyPrimeMinisters;PartIII givesthenamesofCabinetMinisters;PartIVenumeratesMinistersof CabinetrankbutwhowerenotmembersoftheCabinet;PartVcontains informationaboutMinistersofStatewithindependentchargeoftheir Ministries/Departments;PartVIindicatesnamesoftheMinistersofState attachedtothePrimeMinisterandCabinetMinisters;andPartVIIliststhe namesofDeputyMinistersandParliamentarySecretariesholdingtherank -

How Government Interventions Are Propping up Coal Power

Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI publications for their own outputs, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. © Overseas Development Institute 2018. This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for support and advice on the report from: Gireesh Shrimali of the Climate Policy Initiative, India; Ram Shahi of the Energy Infratech Private Limited; Andrew Scott of the Overseas Development Institute; Jesse Burton of the University of Cape Town; Matthew Gray and Lawrence Watson of the Carbon Tracker Initiative; and, Tim Buckley of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. The authors are grateful for communications support from Chris Little, Charlie Zajicek and Hannah Caddick of the Overseas Development Institute. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the European Climate Foundation and Oak Foundation that made this report possible. 3 Contents Acknowledgements 3 List of boxes, tables and figures 5 Acronyms 6 1 Introduction 7 2 India’s electricity transition 8 3 Frameworks and definitions 10 3.1 Framework for analysis 10 3.2 Defining government interventions 11 3.3 Identifying key drivers of asset stranding 11 4 Findings 12 4.1 Government interventions 12 4.2 Drivers -

WEDNESDAY, the 9TH AUGUST, 2000 (The Rajya Sabha Met in The

WEDNESDAY, THE 9TH AUGUST, 2000 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11.00 a.m.) 1. Reference and Homage to martyrs of Freedom Movement and victims of Atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki The Chairman made a reference to the Quit India Movement launched under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and also to the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan on the 6th and 9th August, 1945. The House observed silence, all Members standing, as a mark of respect to the memory of martyrs and freedom fighters and also to the memory of the bomb victims. 11-02 a.m. ______________________________________________________________ _** Spoke in Hindi. 9TH AUGUST, 2000 2. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered. Starred Question No. 241regarding Status of projects. Starred Question No. 242 regarding MDA for handloom products. Starred Question No. 243 regarding Conversion of SU-30 Aircrafts. Answers to remaining Starred Questions (Nos. 244 to 260) were laid on the Table. 3. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos.1861 to 2015 were laid on the Table. 12 Noon 4. Papers Laid on the Table Shri Chennamanevi Vidya Sagar Rao (minister of State in the Ministry of Home Affairs) on behalf of Shri L.K. Advani laid on the Table the following papers: — I. A copy (in English and Hindi) of the Ministry of Home Affairs Notification G.S.R.611 (E) dated 17.7.2000 publishing the National Human Rights Commission (Conditions of Service of Officers and Staff) Rules, 2000, under sub-section (3) of Section 40 of the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993.