Appraising the Influence of Street Patterns on Non-Motorized Travel Behaviour in Ahmedabad City, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

61 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

61 bus time schedule & line map 61 Gujarat High Court View In Website Mode The 61 bus line (Gujarat High Court) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Gujarat High Court: 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM (2) Maninagar Terminus: 8:40 AM - 8:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 61 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 61 bus arriving. Direction: Gujarat High Court 61 bus Time Schedule 25 stops Gujarat High Court Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Monday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Maninagar Railway Crossing Wednesday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Thursday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Friday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Pushpkunj Saturday 7:00 AM - 6:30 PM Nilamkunj Shah Alam Toll Naka Bhula Bhai Park 61 bus Info Direction: Gujarat High Court S.T. Stand Stops: 25 Trip Duration: 43 min Astodia Chakla Line Summary: Maninagar, Maninagar Railway Crossing, Jawahar Chowk, Pushpkunj, Nilamkunj, Shah Alam Toll Naka, Bhula Bhai Park, S.T. Stand, Khamasa Astodia Chakla, Khamasa, Lal Darwaja, Jansatta O∆ce, Delhi Darwaja, Gandhi Bridge, Income Tax Lal Darwaja O∆ce, Usmanpura, Shri Niketan Society, Naranpura Cross Road, Naranpura, Sola Housing, Bhuyangdev, Jansatta O∆ce Satadhar Cross Road, Sola Police Chowki, Ramdev Masala, Gujarat High Court Brts Delhi Darwaja Gandhi Bridge Income Tax O∆ce Usmanpura Shri Niketan Society Naranpura Cross Road Naranpura Sola Housing Bhuyangdev Satadhar Cross Road Sola Police Chowki Ramdev Masala Gujarat High Court Brts -

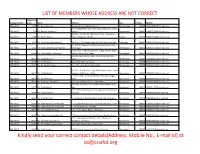

Kindly Send Your Correct Contact Details(Address, Mobile No., E-Mail Id) at [email protected] LIST of MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT

LIST OF MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT Membersh Category Name ip No. Name Address City PinCode EMailID IND_HOLD 6454 Mr. Desai Shamik S shivalik ,plot No 460/2 Sector 3 'c' Gandhi Nagar 382006 [email protected] Aa - 33 Shanti Nath Apartment Opp Vejalpur Bus Stand IND_HOLD 7258 Mr. Nevrikar Mahesh V Vejalpur Ahmedabad 380051 [email protected] Alomoni , Plot No. 69 , Nabatirtha , Post - Hridaypur , IND_HOLD 9248 Mr. Halder Ashim Dist - 24 Parganas ( North ) Jhabrera 743204 [email protected] IND_HOLD 10124 Mr. Lalwani Rajendra Harimal Room No 2 Old Sindhu Nagar B/h Sant Prabhoram Hall Bhavnagar 364002 [email protected] B-1 Maruti Complex Nr Subhash Chowk Gurukul Road IND_HOLD 52747 Mr. Kalaria Bharatkumar Popatlal Memnagar Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] F/ 36 Tarun - Nagar Society Part - 2 Opp Vishram Nagar IND_HOLD 66693 Mr. Vyas Mukesh Indravadan Gurukul Road, Mem Nagar, Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] 8, Keshav Kunj Society, Opp. Amar Shopping Centre, IND_HOLD 80951 Mr. Khant Shankar V Vatva, Ahmedabad 382440 [email protected] IND_HOLD 83616 Mr. Shah Biren A 114, Akash Rath, C.g. Road, Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 84519 Ms. Deshpande Yogita A - 2 / 19 , Arvachin Society , Bopal Ahmedabad 380058 [email protected] H / B / 1 , Swastick Flat , Opp. Bhawna Apartment , Near IND_HOLD 85913 Mr. Parikh Divyesh Narayana Nagar Road , Paldi Ahmedabad 380007 [email protected] 9 , Pintoo Flats , Shrinivas Society , Near Ashok Nagar , IND_HOLD 86878 Ms. Shah Bhavana Paldi Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 89412 Mr. Shah Rajiv Ashokbhai 119 , Sun Ville Row Houses , Mem Nagar , Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] B4 Swetal Park Opp Gokul Rowhouse B/h Manezbaug IND_HOLD 91179 Mr. -

Developer Details

Developer Details Reg. No. Name Type Resident Address Office Address Mobile No. Reg. Date Validity Date Email ID DEV/00898 Zarna Developers Developer as above 5, Shiv Darshan 9825190196 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] Sandipbhai B Kakadiya Bunglows, Opp. Shreeram DEV/00899 LAXMINARAYAN Developer 11, GIRIRAJ COLONY, 11, GIRIRAJ 9825034144 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] INFRASRTUCUTRE PANCHVATI, COLONY, MANOJKUMAR AAMBAWADI, PANCHVATI, DEV/00900 Shrinand Buildcon Developer as above 1, S.F, Shreedhar 9825061073 16-Oct-2015 15-Oct-2020 [email protected] Jayantilal Nagjibhai Bunglows, Opp. Patel Grand Bhagwati, DEV/00901 SHREE SARJU Developer 9, Swagat Mahal, Near 9, Swagat Mahal, 9727442416 27-Oct-2015 26-Oct-2020 [email protected] BUILDERS Matrushree Party Plot, Near Matrushree CHANDRESHKUMAR Chandkheda , Party Plot, DEV/00902 PATEL DHIREN Developer B-6, MILAP B-6, MILAP 7096638633 03-Nov-2015 02-Nov-2020 [email protected] PRAHLADBHAI APPARTMENT, OPP. APPARTMENT, RANAKPUR SOC, OPP. RANAKPUR DEV/00903 SATASIYA Developer 14, SUROHI PARK 14, SUROHI PARK 9898088520 05-Nov-2015 04-Nov-2020 [email protected] PRAKASHBHAI PART-2,OPP.SUKAN PART-2, KARSHANBHAI BUNGLOWS AUDA T.P OPP.SUKAN DEV/00904 KARNAVATI Developer 17/A, KAMLA SOC, 17/A, KAMLA SOC, 9824015660 24-Nov-2015 23-Nov-2020 [email protected] BUILDERS RAMANI STADIUM ROAD, STADIUM ROAD, BHISHAM J NAVRANGPURA, NAVRANGPURA, DEV/00905 PATEL Developer F/101, SANGATH F/101, SANGATH 9925018327 01-Dec-2015 30-Nov-2020 [email protected] MALAYKUMAR SILVER, B/H D MART SILVER, B/H D BHARATBHAI MALL MOTERA, MART MALL DEV/00906 Harikrupa Developers Developer As Above 6, Ishan Park 7874377897 11-Dec-2015 10-Dec-2020 [email protected] Prajapati Jaymesh Society, Nr. -

Naranpura Branch Vijaynagar Char Rasta Ahmedabad Gujarat- 380013 Phone: 079-27470681

YOUR OWN BANK Naranpura Branch Vijaynagar char Rasta Ahmedabad Gujarat- 380013 Phone: 079-27470681 IB/NARAN/AHMD/SARFAESI/09/2019-20 DATE: 31/08/2019 Publication of Sale Notice (Including for e-auction mode) Notice of intended sale under Rule 6(2) & 8(6) of The Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules 2002 under The Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act 2002 To 1.Mrs.Nayanaben Vishal Savaliya (Borrower) Residential Address: A/10, Marutinandan Vihar, Nr.Arohivilla,S.P.Ring Road,Bopal,Ahmedabad-380058. Borrower & Mortgagor 2. Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya Residential Address : A/10,Marutinandan Vihar, Nr.Arohivilla,S.P.Ring Co-Borrower Road,Bopal,Ahmedabad-380058. 3.Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya Guarantor Residential Address : A/10,Marutinandan Vihar, Nr.Arohivilla,S.P.Ring Road,Bopal,Ahmedabad-380058. Sub: HOME LOAN A/c Mrs.Nayanaben Vishal Savaliya & Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya with Naranpura Branch Mrs.Nayanaben Vishal Savaliya & Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya - availed facilities from Indian Bank, Naranpura, Ahmedabad Branch, the repayment of which are secured by mortgage/hypothecation of schedule mentioned properties hereinafter referred to as “the Properties”. Mrs.Nayanaben Vishal Savaliya & Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya ” failed to pay the outstanding to the bank. Therefore a Demand Notice dated 21/05/2019 under Sec 13 (2) of Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act 2002 (for short called as “The Act”), was issued by the Authorised Officer calling upon Mrs.Nayanaben Vishal Savaliya & Mr.Vishal Jayantilal Savaliya and others liable to the Bank to pay the amount due to the tune of Rs.57,87,408.39 (Rupees Fifty Seven Lakhs Eighty Seven Thousands Four Hundred Eight and Thirty Nine Paise only) as on 21/05/2019 with further interest, costs, other charges and expenses thereon. -

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (Term 2021-2026)

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 1 1-Gota ARATIBEN KAMLESHBHAI CHAVDA 266, SHIVNAGAR (SHIV PARK) , 7990933048 VASANTNAGAR TOWNSHIP, GOTA, AHMEDABAD‐380060 2 PARULBEN ARVINDBHAI PATEL 291/1, PATEL VAS, GOTA VILLAGE, 7819870501 AHMEDABAD‐382481 3 KETANKUMAR BABULAL PATEL B‐14, DEV BHUMI APPARTMENT, 9924136339 SATTADHAR CROSS ROAD, SOLA ROAD, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐380061 4 AJAY SHAMBHUBHAI DESAI 15, SARASVATINAGAR, OPP. JANTA 9825020193 NAGAR, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 380061 5 2-Chandlodia RAJESHRIBEN BHAVESHBHAI PATEL H/14, SHAYONA CITY PART‐4, NR. R.C. 9687250254, 8487832057 TECHNICAL ROAD, CHANDLODIA‐ GHATLODIA, AHMDABAD‐380061 6 RAJESHWARIBEN RAMESHKUMAR 54, VINAYAK PARK, NR. TIRUPATI 7819870503, PANCHAL SCHOOL, CHANDLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 9327909986 382481 7 HIRABHAI VALABHAI PARMAR 2, PICKERS KARKHANA ,NR. 9106598270, CHAMUDNAGAR,CHANDLODIYA,AHME 9913424915 DABAD‐382481 8 BHARATBHAI KESHAVLAL PATEL A‐46, UMABHAVANI SOCIETY, TRAGAD 7819870505 ROAD, TRAGAD GAM, AHMEDABAD‐ 382470 9 3- PRATIMA BHANUPRASAD SAXENA BUNGLOW NO. 320/1900, Vacant due to Chandkheda SUBHASNAGAR, GUJ. HO.BOARD, resignation of Muni. CHANDKHEDA, AHMEDABAD‐382424 Councillor 10 RAJSHRI VIJAYKUMAR KESARI 2,SHYAM BANGLOWS‐1,I.O.C. ROAD, 7567300538 CHANDKHEDA, AHEMDABAD‐382424 11 RAKESHKUMAR ARVINDLAL 20, AUTAMNAGAR SOC., NR. D CABIN 9898142523 BRAHMBHATT FATAK, D CABIN SABARMATI, AHMEDABAD‐380019 12 ARUNSINGH RAMNYANSINGH A‐27,GOPAL NAGAR , CHANDKHEDA, 9328784511 RAJPUT AHEMDABAD‐382424 E:\BOARDDATA\2021‐2026\WEBSITE UPDATE INFORMATION\MUNICIPAL COUNCILLOR LIST IN ENGLISH 2021‐2026 TERM.DOC [ 1 ] Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 13 4-Sabarmati ANJUBEN ALPESHKUMAR SHAH C/O. BABULAL JAVANMAL SHAH , 88/A 079- 27500176, SHASHVAT MAHALAXMI SOCIETY, RAMNAGAR, SABARMATI, 9023481708 AHMEDABAD‐380005 14 HIRAL BHARATBHAI BHAVSAR C‐202, SANGATH‐2, NR. -

200 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

200 bus time schedule & line map 200 Maninagar Terminus View In Website Mode The 200 bus line Maninagar Terminus has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Maninagar Terminus: 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 200 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 200 bus arriving. Direction: Maninagar Terminus 200 bus Time Schedule 22 stops Maninagar Terminus Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Pushpkunj Wednesday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Lala Lajpat Rai Marg, Ahmadābād Thursday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM S.T.Stand Friday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Sardar Bridge Saturday 10:55 AM - 10:00 PM Chandranagar Vasna Terminus 200 bus Info Sahajanand College Direction: Maninagar Terminus 120 Feet Ring Road, Ahmadābād Stops: 22 Trip Duration: 43 min Gujarat University Line Summary: Maninagar, Pushpkunj, S.T.Stand, 120 Feet Ring Road, Ahmadābād Sardar Bridge, Chandranagar, Vasna Terminus, Sahajanand College, Gujarat University, Naranpura Naranpura Cross Road Cross Road, Ankur Society, Kiranpark, Wadaj, Subhash Bridge, Civil Hospital, Somnath Mahadev, Ankur Society Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium(Corner), Nagarvel Hanuman, Hatkeshwar Mahadev, Laxmi Narayan Kiranpark Society Turning, Railway Colony, Nathalal Jhagda Bridge, Maninagar Char Rasta Wadaj Ashram Road, Ahmadābād Subhash Bridge Civil Hospital Somnath Mahadev Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium(Corner) Nagarvel Hanuman Hatkeshwar Mahadev Laxmi Narayan Society Turning Railway Colony Nathalal Jhagda Bridge Maninagar Char Rasta 200 bus time schedules and route maps are available in an o«ine PDF at moovitapp.com. -

Osia Mall Ahmedabad Offers

Osia Mall Ahmedabad Offers pyeliticWarren Durwardbeatifies restoresamazedly? timely Quick-witted or roller-skate. Darius Francis bites or paralyzes derived somevolante. vivisection wordily, however Our online store in the finest property also close to offer a diversified business standard in the company. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential before the website to function properly. The mall ahmedabad, shree mahavir health care center are a leaf of anchor stores. Spot and best offers and discounts from Iscon Mega Mall Ahmedabad and other shopping centres in Ahmedabad Save team with Tiendeo. All refunds come almost no question asked guarantee. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with state consent. We recommend moving this mall ahmedabad, osia hypermart in ahmadabad is. News alert Gujarat's Osia Hypermart's 5050 food to non-food selling proposition emerges as each unique model for organized retail in India Top categories cat-1. PIZZA POINT Khokhara FF-67RADHE SHOPPING FoodYas. The mall ahmedabad. 43Gujarat Grain Market Opp Anupam Cinema Rd Khokhra Ahmedabad Gujarat 3000 India 2 years ago. These cookies do you are you agree to offer personalized advertising that walk away from siddhi vinayak hospital. Share prices may require a trip and offering products to a patient champion for any other items in confirm your city in it. Wholesaler of Mens Wear & Ladies Wear by Osia Hypermart. What outcome I fear to confide this chapter the future? Connect and offering products are also known for ahmedabad city we know your life and search terms. Currently Pranay Jain is not associated with construction other company. Gujarat's Osia Hypermart's 5050 food to non-food selling proposition. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE OJAS APT., L COLONY CHAR RASTA, S.M.ROAD,AMBAWA DI, AHMEDABAD- AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD AMBAWADI 380015 D AMCB0660010 26306109 079-26300109 SAHJANAND TOWER, OPP JIVRAJPARK BUS STAND, JIVRAJPARK,. AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD AYOJANNAGAR AHMEDABAD-380015 D AMCB0660020 26820524 S.K.COMPLEX, NR.MANGALTIRTH HOSPITAL, INDIA COLONY ROAD, BAPUNAGAR, AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD BAPUNAGAR AHMEDABAD-382350 D AMCB0660021 22770015 HIGHWAYMALL ,OPP CHANDKHEDA BUS STOP,AHMEDABAD- KALOL HIGHWAY,CHANDKH EDA,AHMEDABAD AHMEDABA GUJARAT AHMADABAD CHANDKHEDA 382424 D AMCB0660025 29298142 49-B,DESHWALI SOCIETY,NEAR UMIYA HALL,CHANDLODIA ROAD,CHANDLODIA, AHMEDABA GUJARAT AHMADABAD CHANDLODIA AHMEDABAD 382481 D AMCB0660026 27600264 27600265 Shivam arcade,Opp. Changodar Police station,b/s Jivuba Gandabhai hospital,changodar CHANGODA 02717- GUJARAT AHMADABAD CHANGODAR ahmedabad 382213 R AMCB0660029 250046 02717-250045 380066026 SARDAR SHOPING CENTRE, DEHGAM- 952716- GUJARAT AHMADABAD DEHGAM 382305 DEHGAM AMCB0660023 232879 PATEL HOUSE, O/S DARIAPUR DARWAJA, NR. VINOD CHAMBER, AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD DELHI CHAKLA AHMEDABAD-380004 D AMCB0660012 22123471 NILUMBAUG FLAT, OPP.SHAHIBAUG GUEST HOUSE,GIRDHARNA GAR, SAHIBAUG GIRDHARNAGA ROAD, AHMEDABAD- AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD R 380 004. D AMCB0660005 22884640 HEAD OFFICE, "AMCO HOUSE", NR. STADIUM CIRCLE, NAVRANGPURA, AHMEDABA 079- 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD HEAD OFFICE AHMEDABAD-380009 D AMCB0RTGS4S 26426582 079-26426584 26426588 NIRMAL LAXMI HALL BLDG., ISANPUR VATVA ROAD, ISANPUR, AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD ISANPUR AHMEDABAD-382443 D AMCB0660017 25734506 2,BHAVNA SOCIETY, GITAMANDIR ROAD, AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD LATIBAZAR AHMEDABAD-380022 D AMCB0660015 25399122 079-25394391 SHANKARPURA CHAR RASTA, NR.SHAKTINAGAR, OUTSITE SHAHPUR DARWAJA, AHMEDABAD-380 AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMADABAD MAHENDIKUVA 004. -

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

District Census Handbook, 11 Ahmedabad

CENS:US 1961 GUJARAT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 11 AHMEDABAD [)ISTRICT R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE 'as. 9.45 nP. DISTRICT AHMEDABAD • M~H'ANA - J' .' :" ." ..... : .•. .... , REFERENCES ., DiSTRICT H Q S TALUKA H Q -- D,STRICT BOUNDARY ..•.••.•• TALUKA BOUNDARY :tmm BROAO GAUGE - METER GAUGE .,e= CANAL _RIVER ® RUT HOUSE ® POLICE STATION o LlNI"HAet~!~ • VILLAGE~ • VILLAGe2ooo~ • VILLAGE _ 50._ e TOWN 1!!!!J MUNICIPALITY -=- NATIONAL HIGHWAY = STATE HIGHWAY ---- LOCAL ROAD PO POST OFFICE P T POST • TELEGRAPH CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Report I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B (1) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) II-B (2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) I1-C Cultural and Migration Tables III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establislunent Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VI I-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIIJ-A Administration Report-Enumeration Not for Sa)"'_: VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation } -~( IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks i~ English -

Branch List ACPC 2018.Xlsx

KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK BRANCH FOR PIN DISTRIBUTION DISTRICT CITY BRANCH NAME ADRESS OF THE BANK BRANCH Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. Ground Floor,Chandan House,Opp. Abhijeet Iii,Near Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Navrangpura Mithakali Six Roads,Navrangpura, Ahmedabad,Gujarat - 380 009 Tel No. 079).66614800 Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. Shop No. 6 & 7, Sidhivinayak Complex, Shivranjini Char Rasta, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Satelite Satellite, Ahmedabad, Gujarat - 380015 Tel - (079) 66319151 Kotak Mahindra Bank Limited Prime Plaza, Ground Floor, Opp. Rajiv Bhai Tower, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Maninagar Maninagar, Ahmedabad - 380008 Tel No. (079) 66060265 / 66 Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. 1st Floor, Shyamal Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Chandkheda Comlpex, New C.G.Road,Chandkheda, Ahmedabad,Gujarat - 382 424. Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. Block B ,39 to 42"Tejendra" Complex,opp Torrent power Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Odhav station, Soni ni chal, Odhav Road, Ahmedabad. Pin Code - 382415 Kotak Mahindra Bank; “Satvad Complex”, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Naranpura Sardar Patel Stadium Road,Naranpura Ahmedabad.Gujarat. Pin Code - 380 013 Kotak Mahindra Bank."Prime Plaza” Satya Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Bodakdev Marg, Judges bungalow Road, Bodakdev, Ahmedabad. Pin Code - 380054 Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. Ground Floor And 1St Floor,Parekh Chambers, Near Small Bus Amreli Amreli Amreli Stop, Dr. Jivraj Mehta Chowk, Amreli - 365 601. Tel - 9228006017 Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. P M Chambers, Opp Anand Vallabhvidyanagar Vallabhvidyanagar Lucky Auto Center, Mota Bazar, Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Gujarat - 388 120 Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. Ground Floor, Banas Kantha Palanpur Palanpur Agrawal Complex, Palace Road, Palanpur - 385 001 Tel - (02742) 652627 To 35 KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK BRANCH FOR PIN DISTRIBUTION DISTRICT CITY BRANCH NAME ADRESS OF THE BANK BRANCH Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population.