Paul Tomlinson Compiled Harry Harrison: an Annotated Bibliography Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: June 11, 2019 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] 2019 DATE local EVENT NAME WHERE TYPE WEBSITE LINK JUNE 12-16 OH ORIGINS GAME FAIR Columbus Conv Ctr, Columbus, OH gaming, anime, media https://www.originsgamefair.com/ FRAZIER HINES, WENDY PADBURY, Mecedes Lackey, Larry Dixon, Charisma Carpenter, Amber Benson, Nicholas Brendon, Juliet Landau, Elisa Teague, Lisa Sell, JUNE 13-16 Phil WIZARD WORLD Philadelphia, PA comics & media con wizardworld.com Lana Parrilla, Ben McKenzie, Morena Baccarin, Ian Somerhalder, Rebecca Mader, Jared Gilmore, Mehcad Brooks, Jeremy Jordan, Hale Appleman, Dean Cain, Holly Marie Combs, Brian Krause, Drew Fuller, Sean Maher, Kenvin Conroy, Lindsay jones, Kara Eberle, Arryb Zech, Barbara Dunkelman, Edward Furlong, Adam Baldwin, Jewel Staite, Thomas Ian Nicholas, Chris Owen, Ted Danson, Cary Elwes, Tony Danza, George Wendt, OUT: Stella Maeve JUNE 14-16 ONT YETI CON Blue Mountain Resort, Blue Mtn, Ont (near Georgian Bay) https://www.yeticon.org/ Kamui Cosplay, Nipah Dubs, James Landino, Dr Terra Watt, cosplayers get-away weekend JUNE 14-16 TX CELEBRITY FAN FEST Freeman Coliseum, San Antonio, TX media & comics https://pmxevents.com Jeremy Renner, Paul Bettany, Benedict Wong, Jason Momoa, Amber Heard, Dolph Lundgren, Walter Koenig, Joe Flannagan, Butch Patrick, Robert Picardo JUNE 15 FLA TIME LORD FEST U of North Florida, Jacksonville, -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Quasiquote #9

“9” Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the gene pool, up pops a shark, with Henry Winkler chasing after it on a motorbike. Three full years after issue eight, QUASIQUOTE 9 makes its bow in April 2012. All the usual things apply: its editor is Sandra Bond, 40 Cleveland Park Avenue, London E17 7BS; it is available by editorial fiat, except if delivered by car, when it comes in the editorial Saab; monetary subscriptions and stamps are unnecessary but accepted at a push; contributors and correspondents are encouraged to e-mail [email protected]; insurgence against fwa and fwuk is likewise encouraged; an apple a day keeps the doctor away. contents FRONT COVER: Dan Steffan p3: HEAVY IN THE AIR: Andy Porter p5: A TISSUE: Tim C. Marion p6: HOTEL PREVIA: Rob Jackson p15: EASTERCON 1978 ART PORTFOLIO p20: THE EXPLORATION OF LOGICAL PARADOXES: Robert Sheckley interviewed by Leroy Kettle p31: THE MISSED OPPORTUNITIES OF ERIC FRANK RUSSELL: Peter Weston p33: ISH MAIL: letter column p39: WATCH OUT FOR STOBOR: editorial and closing thoughts BACK COVER: D West INTERIOR ART this issue: p2, p5, Steve Stiles: p3, p33, p35,p39, William Rotsler: p14, John Toon; p32, Marc Schirmeister. HEAVY IN THE AIR by Andy Porter Last night, January 8th 2011, I was doing my usual tossing and turning while I tried to get to sleep, my mind racing in its usual rapidfire way, refusing to calm down. A gunman in Arizona shot politician Gabrielle Giffords; as well as critically wounding her, he killed six bystanders. -

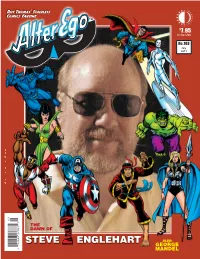

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

SF Commentary 41-42

S F COMMENTARY 41/42 Brian De Palma (dir): GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT Bruce Gillespie: I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS (86) . ■ (SFC 40) (96) Philip Dick (13, -18-19, 37, 45, 66, 80-82, 89- Bruce Gillespie (ed): S F COMMENTARY 30/31 (81, 91, 96-98) 95) Philip Dick: AUTOFAC (15) Dian Girard: EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY (64) Philip Dick: FLOW MY TEARS THE POLICEMAN SAID Victor Gollancz Ltd (9-11, 73) (18-19) Paul Goodman (14). Gordon Dickson: THINGS WHICH ARE CAESAR'S (87) Giles Gordon (9) Thomas Disch (18, 54, 71, 81) John Gordon (75) Thomas Disch: EMANCIPATION (96) Betsey & David Gorman (95) Thomas Disch: THE RIGHT WAY TO FIGURE PLUMBING Granada Publishing (8) (7-8, 11) Gunter Grass: THE TIN DRUM (46) Thomas Disch: 334 (61-64, 71, 74) Thomas Gray: ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCH Thomas Disch: THINGS LOST (87) YARD (19) Thomas Disch: A VACATION ON EARTH (8) Gene Hackman (86) Anatoliy Dneprov: THE ISLAND OF CRABS (15) Joe Haldeman: HERO (87) Stanley Donen (dir): SINGING IN THE RAIN (84- Joe Haldeman: POWER COMPLEX (87) 85) Knut Hamsun: MYSTERIES (83) John Donne (78) Carey Handfield (3, 8) Gardner Dozois: THE LAST DAY OF JULY (89) Lee Harding: FALLEN SPACEMAN (11) Gardner Dozois: A SPECIAL KIND OF MORNING (95- Lee Harding (ed): SPACE AGE NEWSLETTER (11) 96) Eric Harries-Harris (7) Eastercon 73 (47-54, 57-60, 82) Harry Harrison: BY THE FALLS (8) EAST LYNNE (80) Harry Harrison: MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM! (62) Heinz Edelman & George Dunning (dirs): YELLOW Harry Harrison: ONE STEP FROM EARTH (11) SUBMARINE (85) Harry Harrison & Brian Aldiss (eds): THE -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Brum Group News the Monthly Newsletter of the BIRMINGHAM SCIENCE FICTION GROUP MAY 2021 Issue 596 Honorary President: CHRISTOPHER PRIEST

Brum Group News The Monthly Newsletter of the BIRMINGHAM SCIENCE FICTION GROUP MAY 2021 Issue 596 Honorary President: CHRISTOPHER PRIEST Committee: Carol Goodwin (Chair); Pat Brown (Treasurer); Dave Corby (secretary); Theresa Derwin (Publicity Officer); Carol Goodwin (Newsletter Editor); Ian Morley (Membership Secretary); Novacon 50 Chair: Alice Lawson & Tony Berry website: Email: www.birminghamsfgroup.org.uk [email protected] Facebook: Twitter: www.facebook.com/groups/ @BirminghamSF BirminghamSFGroup Carrie Vaughn May 14th at 7:45 pm One of the advantages of an online meeting is that we are far less restricted by geography. This month therefore we have an international guest and are delighted to welcome the award-winning Science Fiction and Fantasy author Carrie Vaughn. Carrie Vaughn's work includes the Philip K. Dick Award- winning novel BANNERLESS, the New York Times bestselling Kitty Norville urban fantasy series, and over twenty novels and upwards of 100 short stories, two of which have been finalists for the Hugo Award. Her most recent work includes a June 11th - 50th Birthday celebrations – details to be confirmed Kitty spin-off collection, THE IMMORTAL CONQUISTADOR, and a pair of novellas about Robin Hood's children, THE GHOSTS OF SHERWOOD and THE HEIRS OF LOCKSLEY. She's a contributor to the Wild Cards series of shared world superhero books edited by George R. R. Martin and a graduate of the Odyssey Fantasy Writing Workshop. A bona fide Air Force “brat” (her father served on a B-52 flight crew during the Vietnam War), Carrie grew up all over the U.S. but managed to put down roots in Colorado, in the Boulder area, where she pursues an endlessly growing list of hobbies and enjoys the outdoors as much as she can. -

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES Gardner Dozois, Ed.; Throy, Jack Vance

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES Gardner Dozois, ed.; Throy, Jack Vance. ABA draws 27,000 ...............................................6 Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe:............................... 27 Baen Unveils New L ogo..................................... 6 Hearts, Hands and Voices aka The Broken Land, Fritz Leiber V Margo Skinner............................6 Ian McDonald; Tales of Chicago, R.A. Lafferty; Clarke Takes Plunge............................................ 6 Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy, David THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Foundation: The Movie....................................... 6 Ketterer; Fairy Tale Romance: The Grimms, Wyatt Quits Ballantine Books............................7 Basile, and Perrault, James M. McGlathery. (ISSN-0047-4959) DimeNovels Debacle........................................... 7 Reviews by Dan Chow:...................................... 29 EDITOR & PUBLISHER Bloch’s 75th Birthday B ash.................................9 Beachhead, Jack Williamson; Labyrinth of Night, Charles N. Brown THE DATA FILE Allen Steele; Mining the Oort, Frederik Pohl; ASSOCIATE EDITOR Worldcon News....................................................7 The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Ninth Annual Faren C. Miller Bookstore News...................................................7 Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed. ASSISTANT EDITORS Satanic Verses Update........................................ 7 Reviews by Carolyn Cushman:..........................31 Marianne S. Jablon Copyright News..................................................69 -

SF Commentary 83

SSFF CCoommmmeennttaarryy 8833 October 2012 GUY SALVIDGE ON THE NOVELS OF PHILIP K. DICK ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: Brian ALDISS Eric MAYER John BAXTER Cath ORTLIEB Greg BENFORD Rog PEYTON Helena BINNS Mark PLUMMER Damien BRODERICK Franz ROTTENSTEINER Ned BROOKS Yvonne ROUSSEAU Ian COVELL David RUSSELL Bruce GILLESPIE Darrell SCHWEITZER Fenna HOGG Steve SNEYD John-Henri HOLMBERG Ian WATSON Carol KEWLEY Taral WAYNE Robert LICHTMAN Frank WEISSENBORN Patrick MCGUIRE Ray WOOD Murray MACLACHLAN Martin Morse WOOSTER Tim MARION Cover: Fenna Hogg S F Commentary 83 SF Commentary No 83, October 2012, 107 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie ([email protected]), 5 Howard St., Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia, and http://efanzines.com/SFC/SFC83.pdf. All correspondence: [email protected]. Member fwa. First edition and primary publication is electronic. All material in this publication was contributed for one-time use only, and copyrights belong to the contributors. Alternate editions: * A very limited number of print copies are available. Enquiries to the editor. * The alternate PDF version is portrait-shaped, i.e. it looks the same as the print edition, but with colour graphics. Front cover: Melbourne graphic artist Fenna Hogg’s cover does not in fact portray Philip K. Dick wearing a scramble suit. That’s what it looks like to me. It is actually based on a photograph of Melbourne writer and teacher Steve Cameron, who arranged with Fenna for its use as a cover. Graphic: Carol Kewley (p. 105). Photographs: Damien Broderick (p. 5); Guy Salvidge (p. 10); Jim Sakland/Dick Eney (p. 67); Jerry Bauer (p. -

Star Trek, Nyota Uhura, and the Female Role

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Projects Capstone Projects 2020 Expectation Versus Reality: Star Trek, Nyota Uhura, and the Female Role Cecelia Otto-Griffiths Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Otto-Griffiths, C. (2020). Expectation versus reality: Star Trek, Nyota Uhura, and the female role [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/1016/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Expectation Versus Reality: Star Trek, Nyota Uhura, and the Female Role By Cecelia Otto-Griffiths [email protected] Advisor Dr. Laura Jacobi A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In Communication Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2020 i April 13, 2020 Expectation Versus Reality: Star Trek, Nyota Uhura, and the Female Role Cecelia Otto-Griffiths This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the student’s committee.