Tate Modern: the First Five Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Wars at MT

NEW STAR WARS AT MADAME TUSSAUDS UNIQUE INTERACTIVE STAR WARS EXPERIENCE OPENS MAY 2015 A NEW multi-million pound experience opens at Madame Tussauds London in May, with a major new interactive Star Wars attraction. Created in close collaboration with Disney and Lucasfilm, the unique, immersive experience brings to life some of film’s most powerful moments featuring extraordinarily life- like wax figures in authentic walk-in sets. Fans can star alongside their favourite heroes and villains of Star Wars Episodes I-VI, with dynamic special effects and dramatic theming adding to the immersion as they encounter 16 characters in 11 separate sets. The attraction takes the Madame Tussauds experience to a whole new level with an experience that is about much more than the wax figures. Guests will become truly immersed in the films as they step right into Yoda's swamp as Luke Skywalker did in Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back or feel the fiery lava of Mustafar as Anakin turns to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith. Spanning two floors, the experience covers a galaxy of locations from the swamps of Dagobah and Jabba’s Throne Room to the flight deck of the Millennium Falcon. Fans can come face-to-face with sinister Stormtroopers; witness Luke Skywalker as he battles Darth Vader on the Death Star; feel the Force alongside Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn when they take on Darth Maul on Naboo; join the captive Princess Leia and the evil Jabba the Hutt in his Throne Room; and hang out with Han Solo in the cantina before stepping onto the Millennium Falcon with the legendary Wookiee warrior, Chewbacca. -

Discover London

Discover London Page 1 London Welcome to your free “Discover London” city guide. We have put together a quick and easy guide to some of the best sites in London, a guide to going out and shopping as well as transport information. Don’t miss our local guide to London on page 31. Enjoy your visit to London. Visitor information...........................................................................................................Page 3 Tate Modern....................................................................................................................Page 9 London Eye.....................................................................................................................Page 11 The Houses of Parliament...............................................................................................Page 13 Westminster Abbey........................................................................................................Page 15 The Churchill War Rooms...............................................................................................Page 17 Tower of London............................................................................................................Page 19 Tower Bridge..................................................................................................................Page 21 Trafalgar Square.............................................................................................................Page 23 Buckingham Palace.........................................................................................................Page -

Barbican Art Gallery 2020 Exhibition Programme

Barbican Art Gallery 2020 Exhibition Programme Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art Until 19 January 2020, Barbican Art Gallery Last few weeks Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art explores the social and artistic role of cabarets, cafés and clubs around the world. Spanning the 1880s to the 1960s, the exhibition presents a dynamic and multi-faceted history of artistic production. The first major show staged on this theme, it features both famed and little-known sites of the avant-garde – these creative spaces were incubators of radical thinking, where artists could exchange provocative ideas and create new forms of artistic expression. Into the Night offers an alternative history of modern art that highlights the spirit of experimentation and collaboration between artists, performers, designers, musicians and writers such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Loïe Fuller, Josef Hoffmann, Giacomo Balla, Theo van Doesburg and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, as well as Josephine Baker, Jeanne Mammen, Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Ramón Alva de la Canal and Ibrahim El-Salahi. For information and images please visit: www.barbican.org.uk/IntoTheNightNews Trevor Paglen: From ‘Apple’ to ‘Anomaly’ (Pictures and Labels) Selections from the ImageNet dataset for object recognition Until 16 February 2020, The Curve Free admission Last few weeks Barbican Art Gallery has commissioned the artist Trevor Paglen to create a new work for The Curve. Paglen’s practice spans image-making, sculpture, investigative journalism, writing and engineering. Among his primary concerns are learning to see the historical moment we live in, exposing the invisible power structures that underpin the reality of our daily lives and developing the means to imagine alternative futures. -

Event Planner Guide 2020 Contents

EVENT PLANNER GUIDE 2020 CONTENTS WELCOME TEAM BUILDING 17 TRANSPORT 46 TO LONDON 4 – Getting around London 48 – How we can help 5 SECTOR INSIGHTS 19 – Elizabeth Line 50 – London at a glance 6 – Tech London 20 – Tube map 54 – Financial London 21 – Creative London 22 DISCOVER – Medical London 23 YOUR LONDON 8 – Urban London 24 – New London 9 – Luxury London 10 – Royal London 11 PARTNER INDEX 26 – Sustainable London 12 – Cultural London 14 THE TOWER ROOM 44 – Leafy Greater London 15 – Value London 16 Opening its doors after an impressive renovation... This urban sanctuary, situated in the heart of Mayfair, offers 307 contemporary rooms and suites, luxurious amenities and exquisite drinking and dining options overseen by Michelin-starred chef, Jason Atherton. Four flexible meeting spaces, including a Ballroom with capacity up to 700, offer a stunning setting for any event, from intimate meetings to banquet-style 2 Event Planner Guide 2020 3 thebiltmoremayfair.com parties and weddings. WELCOME TO LONDON Thanks for taking the time to consider London for your next event. Whether you’re looking for a new high-tech So why not bring your delegates to the capital space or a historic building with more than and let them enjoy all that we have to offer. How we can help Stay connected Register for updates As London’s official convention conventionbureau.london conventionbureau.london/register: 2,000 years of history, we’re delighted to bureau, we’re here to help you conventionbureau@ find out what’s happening in introduce you to the best hotels and venues, Please use this Event Planner Guide as a create a world-class experience for londonandpartners.com London with our monthly event as well as the DMCs who can help you achieve practical index and inspiration – and contact your delegates. -

Tate Report 2010-11: List of Tate Archive Accessions

Tate Report 10–11 Tate Tate Report 10 –11 It is the exceptional generosity and vision If you would like to find out more about Published 2011 by of individuals, corporations and numerous how you can become involved and help order of the Tate Trustees by Tate private foundations and public-sector bodies support Tate, please contact us at: Publishing, a division of Tate Enterprises that has helped Tate to become what it is Ltd, Millbank, London SW1P 4RG today and enabled us to: Development Office www.tate.org.uk/publishing Tate Offer innovative, landmark exhibitions Millbank © Tate 2011 and Collection displays London SW1P 4RG ISBN 978-1-84976-044-7 Tel +44 (0)20 7887 4900 Develop imaginative learning programmes Fax +44 (0)20 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Strengthen and extend the range of our American Patrons of Tate Collection, and conserve and care for it Every effort has been made to locate the 520 West 27 Street Unit 404 copyright owners of images included in New York, NY 10001 Advance innovative scholarship and research this report and to meet their requirements. USA The publishers apologise for any Tel +1 212 643 2818 Ensure that our galleries are accessible and omissions, which they will be pleased Fax +1 212 643 1001 continue to meet the needs of our visitors. to rectify at the earliest opportunity. Or visit us at Produced, written and edited by www.tate.org.uk/support Helen Beeckmans, Oliver Bennett, Lee Cheshire, Ruth Findlay, Masina Frost, Tate Directors serving in 2010-11 Celeste -

Artist Katie Schwab Joins New Collective to Co-Produce Horniman’S 2019 Studio Exhibition

For immediate release Issued 28 February 2019 Artist Katie Schwab joins new Collective to co-produce Horniman’s 2019 Studio exhibition London-based visual artist Katie Schwab has joined a new Collective of 10 local community members to co-produce the 2019 exhibition in the Horniman Museum and Garden’s new arts space, The Studio. The Collective will explore ideas around ‘memory’ and draw inspiration from the Horniman’s anthropology collections for the next Studio exhibition which will open in October 2019. The exhibition, bringing together new artwork and collections, will be accompanied by a programme of events and activities also co-produced by the Collective. The Collective members collaborating on the exhibition are: Ahmadzia, a volunteer at Southwark Day Centre for Asylum Seekers (SDCAS) and a kite maker, who came to the UK in 2006 from Kunduz, Afghanistan, and is a refugee Carola Cappellari, a photojournalism and documentary photography student who volunteered her skills to produce promotional material for the Indoamerican Refugee and Migrant Organisation, a community-led organisation supporting Latin Americans to build secure and integrated lives in the UK Francis Stanfield, a multi-tasker when it comes to music who describes himself as ‘the original stuporman’. He is influenced by surrealism, films and art, likes ‘anything out of the weird’ and joined the Collective through his involvement with St. Christopher’s Hospice Godfrey Gardin, from Kenya but living in London, who volunteers with SDCAS ‘because it enriches the community where I live’ and who also has an interest in gardening Jacqueline Benn, who has a career background in TV programming planning and immersive theatre, and whose interests lie also in the arts, and producing short films. -

The Wallace Collection — Rubens Reuniting the Great Landscapes

XT H E W ALLACE COLLECTION RUBENS: REUNITING THE GREAT LANDSCAPES • Rubens’s two great landscape paintings reunited for the first time in 200 years • First chance to see the National Gallery painting after extensive conservation work • Major collaboration between the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection 3 June - 15 August 2021 #ReunitingRubens In partnership with VISITFLANDERS This year, the Wallace Collection will reunite two great masterpieces of Rubens’s late landscape painting: A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning and The Rainbow Landscape. Thanks to an exceptional loan from the National Gallery, this is the first time in two hundred years that these works, long considered to be companion pieces, will be seen together. This m ajor collaboration between the Wallace Collection and the National Gallery was initiated with the Wallace Collection’s inaugural loan in 2019 of Titian’s Perseus and Andromeda, enabling the National Gallery to complete Titian’s Poesie cycle for the first time in 400 years for their exhibition Titian: Love, Desire, Death. The National Gallery is now making an equally unprecedented reciprocal loan to the Wallace Collection, lending this work for the first time, which will reunite Rubens’s famous and very rare companion pair of landscape paintings for the first time in 200 years. This exhibition is also the first opportunity for audiences to see the National Gallery painting newly cleaned and conserved, as throughout 2020 it has been the focus of a major conservation project specifically in preparation for this reunion. The pendant pair can be admired in new historically appropriate, matching frames, also created especially for this exhibition. -

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars The South Bank has seen a revolution over the past 04/ THE HEART OF decade, culturally, artistically and architecturally. THE SOUTH BANK Pop up restaurants, food markets, festivals, art 08/ installations and music events have transformed UNIQUE the area, and its reputation as one of London’s LIFESTYLE most popular destinations is now unshakeable. 22/ CULTURAL Some of the capital’s most desirable restaurants and LANDSCAPE bars are found here, such as Hixter, Sea Containers 34/ and the diverse offering of The Shard. Culture has FRESH always had a place here, ever since the establishment PERSPECTIVES of the Festival Hall in 1951. Since then, it has been 44/ NEW joined by global champions of arts and theatre such HORIZONS as the Tate Modern, the National Theatre and the BFI. Arts and culture continues to flourish, and global businesses flock to establish themselves amongst such inspiring neighbours. Influential Blue Chips, global professional and financial services giants and major international media brands have chosen to call this unique business hub home. With world-class cultural and lifestyle opportunities available, the South Bank is also seeing the dawn of some stunning new residential developments. These ground-breaking schemes such as One Blackfriars bring an entirely new level of living to one of the world’s most desirable locations. COMPUTER ENHANCED IMAGE OF ONE BLACKFRIARS IS INDICATIVE ONLY 1 THE HEART OF THE SOUTH BANK THE SHARD CANARY WHARF 30 ST MARY AXE STREET ONE BLACKFRIARS TOWER BRIDGE -

Design of a 45 Circuit Duct Bank

ReturnClose and to SessionReturn DESIGN OF A 45 CIRCUIT DUCT BANK Mark COATES, ERA Technology Ltd, (UK), [email protected] Liam G O’SULLIVAN, EDF Energy Networks, (UK), liam.o’[email protected] ABSTRACT CIRCUIT REQUIREMENTS Bankside power station in London, closed in 1981 but the The duct block was designed to carry the following XLPE substation that is housed in the same building has remained insulated cable circuits without exceeding the operating operational. The remainder of the building has housed the temperature of any cable within the duct block. Tate Modern art gallery since 2000. EDF Energy Networks is now engaged in a project to upgrade and modernise o Four 400/230V circuits with a cyclic loading of 300A. Bankside substation. Part of this work involves the o Twenty 11kV circuits with a cyclic loading of 400A. diversion of about 45 cable circuits into a duct block within o Sixteen 20kV circuits with a cyclic loading of 400A the basement of the substation. The circuits include pilot o Four 66kV circuits with a cyclic loading of 300A circuits, LV circuits and 11 kV, 22 kV, 66kV and 132 kV o Two 132kV circuits with a cyclic loading of 700A circuits. This paper describes the process involved in o Six pilot circuits. designing the duct bank. The cyclic load was taken to be a step wave with 100 % load factor from 08.00hrs to 20.00hrs and 0.8pu from KEYWORDS 20.00hrs to 08.00hrs. Duct bank, Magnetic field, Surface temperature, Cable rating. The cables selected for this installation were of types commonly used by distribution companies in the UK. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

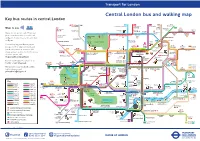

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Art REVOLUTIONARIES Six Years Ago, Two Formidable, Fashionable Women Launched a New Enterprise

Art rEVOLUtIONArIES SIx yEArS AgO, twO fOrmIdAbLE, fAShIONAbLE wOmEN LAUNchEd A NEw ENtErprISE. thEIr mISSION wAS tO trANSfOrm thE wAy wE SUppOrt thE ArtS. thEIr OUtSEt/ frIEzE Art fAIr fUNd brOUght tOgEthEr pAtrONS, gALLErIStS, cUrAtOrS, thE wOrLd’S grEAtESt cONtEmpOrAry Art fAIr ANd thE tAtE IN A whIrLwINd Of fUNdrAISINg, tOUrS ANd pArtIES, thE LIkES Of whIch hAd NEVEr bEEN SEEN bEfOrE. hErE, fOr thE fIrSt tImE, IS thEIr INSIdE StOry. just a decade ago, the support mechanism for young artists in Britain was across the globe, and purchase it for the Tate collection, with the Outset funds. almost non-existent. Government funding for purchases of contemporary art It was a winner all round. Artists who might never have been recognised had all but dried up. There was a handful of collectors but a paucity of by the Tate were suddenly propelled into recognition; the national collection patronage. Moreover, patronage was often an unrewarding experience, both acquired work it would never otherwise have afforded. for the donor and for the recipient institution. Mechanisms were brittle and But the masterstroke of founders Gertler and Peel was that they made it old-fashioned. Artists were caught in the middle. all fun. Patrons were whisked on tours of galleries around the world or to Then two bright, brisk women – Candida Gertler and Yana Peel – marched drink champagne with artists; galleries were persuaded to hold parties into the picture. They knew about art; they had broad social contacts across a featuring collections of work including those by (gasp) artists tied to other new generation of young wealthy; and they had a plan. -

Never-Before-Seen Documents Reveal IWM's Plan for Evacuating Its Art

Never-before-seen documents reveal IWM’s plan for evacuating its art collection during the Second World War Never-before-seen documents from Imperial War Museums’ (IWM) collections will be displayed as part of a new exhibition at IWM London, uncovering how cultural treasures in British museums and galleries were evacuated and protected during the Second World War. The documents, which include a typed notice issued to IWM staff in 1939, titled ‘Procedure in the event of war,’ and part of a collection priority list dated 1938, are among 15 documents, paintings, objects, films and sculptures that will be displayed as part of Art in Exile (5 July 2019 – 5 January 2020). At the outbreak of the Second World War, a very small proportion of IWM’s collection was chosen for special evacuation, including just 281works of art and 305 albums of photographs. This accounted for less than 1% of IWM’s entire collection and 7% of IWM’s art collection at the time, which held works by prominent twentieth- century artists including William Orpen, John Singer Sargent, Paul Nash and John Lavery. Exploring which works of art were saved and which were not, Art in Exile will examine the challenges faced by cultural organisations during wartime. With the exodus of Britain’s cultural treasures from London to safety came added pressures on museums to strike a balance between protecting, conserving and displaying their collections. The works on IWM’s 1938 priority list, 60 of which will be reproduced on one wall in the exhibition, were destined for storage in the country homes of IWM’s Trustees, where it was believed German bombers were unlikely to venture.