A Review of Archaeological Site Records for the Canterbury Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trail Brochure 1 Printed.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Intro: On Track on the Christchurch 4 to Little River Rail Trail Safety First 6 Answers to Common Questions 8 Map of Trail 10 1 Christchurch Cathedral Square 12 to Marshs Road 2 Shands Road to Prebbleton 16 3 Prebbleton to Lincoln 20 4 Lincoln to Neills Road 24 5 Neills Road to Motukarara 28 6 Motukarara to Kaituna Quarry 32 7 Kaituna Quarry to Birdlings Flat 36 8 Birdlings Flat to Little River 40 Plants, Birds and Other Living Things 44 Official Partners 48 2 3 INTRODUCTION For those who want to turn the trip into a multi-day ON TRACK ON THE adventure, there are many options for accommodation along the Trail whether you’re staying in a tent or CHRISTCHURCH prefer something more substantial. There are shuttles TO LITTLE RIVER RAIL TRAIL available if you prefer to ride the trail in only one direction. We welcome you to embark on an historic adventure The Trail takes you from city streets on dedicated along the Christchurch Little River Rail Trail. urban cycleways through to quiet country roads The Rail Trail is a great way to actively explore and over graded off road tracks that are ideal for Christchurch and the beautiful countryside that families and enjoyable to walk or bike for people of surrounds it. all abilities. The ride begins in the heart of Christchurch so make sure to take time to explore the centre of Christchurch which is bustling with attractions and activities for all. See the Christchurch section of this brochure for an introduction to some of the great things on offer in Christchurch! After leaving the city, the route winds its way out into the country along the historic Little River Branch railway line and takes you through interesting towns and villages that are well off the beaten tourist track. -

FERRYMEAD Tram Tracts

FERRYMEAD Tram Tracts The Journal of the Tramway Historical Society Issue 19—October 2017 New Plymouth Trolleybus Closure—50 Years Later Remembering New Zealand’s only provincial trolleybus network. ‘Standard’ 139 On the Move From Kaitorete Spit to Darfield and a bright new future Ferrymead 50 We’re starting to make plans. Can you help? The Tramway Historical Society P. O. Box 1126 , Christchurch 81401 - www.ferrymeadtramway.org.nz First Notch President’s Piece—Graeme Belworthy Hi All, It would appear that the flooding around the ring road September's General Meeting was has been solved with the clearing of the blockages. The the annual dinner the Society Council has been contact about the flooding that occurs holds at this time of year. About 26 in the carpark next to the Tram barn site, and also along attended the evening, a little less our track leading into the village. The problem is a faulty than in past years but those “Flood Valve” which connects a drain down the side of present enjoyed the meal and the our site into the flood retention pond next to Woodhill. socialising. October’s meeting is a That may sound very complicated but the Council agree film evening by David Jones it is their problem and will fix it. covering some of the public The normal maintenance continues around the site. We transport systems in South Africa. now have a secure compound between the containers in As part of this evening I hope to be the corner of the carpark. We still need to find a quali- able to present Driving Certificates to our new drivers. -

A Tour of Christchurch New Zealand Aotearoa & Some of the Sights We

Welcome to a Tour of Christchurch New Zealand Aotearoa & some of the sights we would have liked to have shown you • A bit of history about the Chch FF Club and a welcome from President Jan Harrison New Zealand is a long flight from most large countries New Zealand is made up of two main islands and several very small islands How do we as a country work? • NZ is very multi cultural and has a population of just over 5 million • About 1.6 M in our largest city Auckland • Christchurch has just on 400,000 • Nationally we have a single tier Government with 120 members who are elected from areas as well as separate Maori representation. • Parliamentary system is based on a unitary state with a constitutional monarchy. How has Covid 19 affected us? • Because of being small islands and having a single tier Govt who acted very early and with strong measures Covid 19, whilst having had an impact on the economy, has been well contained • We are currently at level 1 where the disease is contained but we remain in a state of being prepared to put measurers in place quickly should there be any new community transmission. • There are no restrictions on gathering size and our sports events can have large crowds. • Our borders are closed to general visitor entry. • We are very blessed South Island Clubs Christchurch Christchurch Places we like to share with our visiting ambassadors First a little about Christchurch • Located on the east coast of the South Island, Christchurch, whose Maori name is Otautahi (the place of tautahi), is a city of contrasts. -

Sandys Sinks the Sixth Online Move Right Call

Thursday, July 30, 2020 Since Sept 27, 1879 Retail $2.20 Home delivered from $1.40 THE INDEPENDENT VOICE OF MID CANTERBURY Loss of foreign students hits colleges Online move right call P2 Both Ashburton and Mount Hutt colleges are taking a hammering financially due to the loss of foreign fee-paying students. BY SUE NEWMAN Traditionally the college hosts several Until Covid-19, that source had been [email protected] groups of Thai and Japanese students international student fees, Saxon said. Mid Canterbury’s two secondary each year. This year it will host none “This source has now been compro- schools are counting the lost income and Saxon is putting the overall loss of mised. At the moment we’re starting to from international students at well over international student fees at more than tread water, but if the border restric- $100,000 and rising. $100,000. tions are not loosened next year it’ll Both Mount Hutt College and Ashbur- “And into the future, while long term have an impact on staffing. ton College rely on fees from interna- student numbers might increase once “At the end of the day it goes back op- tional students to boost their operating the borders start to open, I don’t think erationally, to what levels schools are fund, but on the back of the Covid-19 there’s any light at the end of the tunnel funded to, to run a modern curriculum. closure of New Zealand’s borders, both for international short stays and they’re It means they’re forced to find other schools have a significantly lower num- the more profitable, generally,” he said. -

Summits and Bays Walks

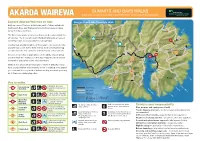

DOC Information Centre Sumner Taylors Mistake Godley Head Halswell Akaroa Lyttelton Harbour 75km SUMMITSFerry AND BAYS WALKS AKAROA WAIREWA Explore the country around Akaroa and Little RiverPort Levy on these family friendly walks Explore Akaroa/Wairewa on foot Choose Your Banks Peninsula Walk Explore some of the less well-known parts of Akaroa Harbour,Tai Tapu Pigeon Bay the Eastern Bays and Wairewa (the Little River area) on these Little Akaloa family friendly adventures. Chorlton Road Okains Bay The three easy walks are accessed on sealed roads suitable for Te Ara P¯ataka Track Western Valley Road all vehicles. The more remote and harder tramps are accessed Te Ara P¯ataka Track Packhorse Hut Big Hill Road 3 Okains Bay via steep roads, most unsuitable for campervans. Road Use the map and information on this page to choose your route Summit Road Museum Rod Donald Hut and see how to get there. Then refer to the more detailed map 75 Le Bons Okains Bay Camerons Track Bay and directions to find out more and follow your selected route. Road Lavericks Ridge Road Hilltop Tavern 75 7 Duvauchelle Panama Road Choose a route that is appropriate for the ability of your group 1 4WD only Christchurch Barrys and the weather conditions on the day. Prepare using the track Bay 2 Little River Robinsons 6 Bay information and safety notes in this brochure. Reserve Road French O¯ nawe Kinloch Road Farm Lake Ellesmere / Okuti Valley Summit Road Walks in this brochure are arranged in order of difficulty. If you Te Waihora Road Reynolds Valley have young children or your family is new to walking, we suggest Little River Rail Trail Road Saddle Hill you start with the easy walk in Robinsons Bay and work your way Lake Forsyth / Akaroa Te Roto o Wairewa 4 Jubilee Road 4WD only up to the more challenging hikes. -

Boat Preference and Stress Behaviour of Hector's Dolphin in Response to Tour Boat Interactions

Boat Preference and Stress Behaviour of Hector’s Dolphin in Response to Tour Boat Interactions ___________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Georgia-Rose Travis ___________ Lincoln University 2008 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. Boat Preference and Stress Behaviour of Hector’s Dolphin in Response to Tour Boat Interactions by Georgia-Rose Travis Dolphins are increasingly coming into contact with humans, particularly where tourism is involved. It has been assumed that such contact causes chronic stress on dolphin populations. This study examined relatively naive populations of Hector's dolphins and their interaction with various watercrafts. Dolphins in New Zealand have been observed using theodolites and boat-based observations over the last two decades, particularly on the east side of the South Island at Akaroa, which is situated on the coast line of Banks Peninsula. This research was undertaken using shore-based theodolite tracking to observe boat activity around the coast of Lyttelton and Timaru and their associated Harbours. Observations were made mostly over two periods each of six months duration and included the months October through to March during the years 2000-2001 and 2001-2002. Observations made during a third period in 2005 were also incorporated for some of the analyses. Field investigations using a theodolite included more than 376 hours/site/season and recorded dolphin behaviour both with and without the presence of tour boats. Of primary interest were the tours, which ran regular trips to observe Cephalorhynchus hectori in their natural habitat. -

The Public Realm of Central Christchurch Narrative

THE PUBLIC REALM OF CENTRAL CHRISTCHURCH NARRATIVE Written by Debbie Tikao, Landscape Architect and General Manager of the Matapopore Charitable Trust. Kia atawhai ki te iwi – Care for the people Pita Te Hori, Upoko – Ngāi Tūāhuriri Rūnanga, 1861 The Public Realm of Central Christchurch Narrative 1 2 CERA Grand Narratives INTRODUCTION This historical narrative weaves together Ngāi Tahu cultural values, stories and traditional knowledge associated with Ōtautahi (Christchurch) and the highly mobile existence of hapū and whānau groups within the Canterbury area and the wider landscape of Te Waipounamu (South Island). The focus of this historical narrative therefore is on this mobile way of life and the depth of knowledge of the natural environment and natural phenomena that was needed to navigate the length and breadth of the diverse and extreme landscape of Te Waipounamu. The story that will unfold is not one of specific sites or specific areas, but rather a story of passage and the detailed cognitive maps that evolved over time through successive generations, which wove together spiritual, genealogical, historical and physical information that bound people to place and provided knowledge of landscape features, mahinga kai and resting places along the multitude of trails that established the basis for an economy based on trade and kinship. This knowledge system has been referred to in other places as an oral map or a memory map, which are both good descriptions; however, here it is referred to as a cognitive map in an attempt to capture the multiple layers of ordered and integrated information it contains. This historical narrative has been written to guide the design of the public realm of the Christchurch central business area, including the public spaces within the East and South frames. -

Nitrate Contamination of Groundwater in the Ashburton-Hinds Plain

Nitrate contamination and groundwater chemistry – Ashburton-Hinds plain Report No. R10/143 ISBN 978-1-927146-01-9 (printed) ISBN 978-1-927161-28-9 (electronic) Carl Hanson and Phil Abraham May 2010 Report R10/143 ISBN 978-1-927146-01-9 (printed) ISBN 978-1-927161-28-9 (electronic) 58 Kilmore Street PO Box 345 Christchurch 8140 Phone (03) 365 3828 Fax (03) 365 3194 75 Church Street PO Box 550 Timaru 7940 Phone (03) 687 7800 Fax (03) 687 7808 Website: www.ecan.govt.nz Customer Services Phone 0800 324 636 Nitrate contamination and groundwater chemistry - Ashburton-Hinds plain Executive summary The Ashburton-Hinds plain is the sector of the Canterbury Plains that lies between the Ashburton River/Hakatere and the Hinds River. It is an area dominated by agriculture, with a mixture of cropping and grazing, both irrigated and non-irrigated. This report presents the results from a number investigations conducted in 2004 to create a snapshot of nitrate concentrations in groundwater across the Ashburton-Hinds plain. It then examines data that have been collected since 2004 to update the conclusions drawn from the 2004 data. In 2004, nitrate nitrogen concentrations were measured in groundwater samples from 121 wells on the Ashburton-Hinds plain. The concentrations ranged from less than 0.1 milligram per litre (mg/L) to more than 22 mg/L. The highest concentrations were measured in the Tinwald area, within an area approximately 3 km wide and 11 km long where concentrations were commonly greater than the maximum acceptable value (MAV) of 11.3 mg/L set by the Ministry of Health. -

Novel Habitats, Rare Plants and Root Traits

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Novel Habitats, Rare Plants and Roots Traits A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science at Lincoln University by Paula Ann Greer Lincoln University 2017 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science. Abstract Novel habitats, rare plants and root traits. by Paula Ann Greer The loss of native plant species through habitat loss has been happening in NZ since the arrival of humans. This is especially true in Canterbury where less than 1% of the lowland plains are believed to be covered in remnant native vegetation. Rural land uses are changing and farm intensification is creating novel habitats, including farm irrigation earth dams. Dam engineers prefer not to have plants growing on dams. Earth dams are consented for 100 years, they could be used to support threatened native plants. Within the farm conversion of the present study dams have created an average of 1.7 hectares of ‘new land’ on their outside slope alone, which is the area of my research. -

GNS Science Consultancy Report 2007/0XX

Natural Hazards in Canterbury - Planning for Reduction - Stage 2 PJ Forsyth GNS Science Report 2008/17 June 2008 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Natural Hazards in Canterbury - Planning for Reduction - Stage 2. Forsyth, P.J. 2008. GNS Science Report 2008/17. 41 p. P. J. Forsyth, GNS Science, Private Bag 1930, Dunedin © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2008 ISSN 1177-2425 ISBN 978-0-478-19624-5 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 2.0 METHODS....................................................................................................................1 3.0 THE CANTERBURY REGION .....................................................................................2 4.0 NATURAL HAZARDS MANAGEMENT CONTEXT ....................................................4 4.1 Natural Hazards Management in New Zealand ................................................................... 4 4.2 Emergency Management in Canterbury............................................................................... 6 4.2.1 Canterbury CDEM online ..................................................................................... 9 5.3 ECan online links................................................................................................................ 11 6.0 DISTRICT PLANNING DOCUMENTS .......................................................................12 -

Maori Rock Drawing: the Theo Schoon Interpretations

MAORI ROCK DRAWING The Thea Schoon Interpretations Robert McDougall Art Gallel)l 704. Chrislchurch City Council New Zealand 03994 MAO MAORI ROCK DRAWING The Theo Schoon Interpretations FOREWORD INTRODUCTION SOUTH ISLAND ROCK DRAWINGS The earliest images crealed in New In many parts or the South Island, or even the type of animal being Zealand. thai have survived \0 our time. particularly where smooth surfaced portrayed, and some of these may well are Ihe drawings made In caves and outcrops 01 Ilmesione occur. prehiS represent mylhlcal monsters or Maori shellers by Maori artists as long ago toric Maori drawmgs can be round on legend such as the tamwha - or, as as the hUeenth century or earlier. the rock surface. where they have one leadlllg ethnologist put II. race survlyed ror several centuries. memones of crealures Irom another They have intrigued archaeologists, land. Occaslonafly the drawlOgs are m historians, and anlsts, who. admiring The reason for the aSSOCiation 01 lhe OUlhne, but most are blocked Ill. Ihe strength and elegance 01 the drawmgs With Ilmesione outcrops IS somehmes With a blank Slflp running deSigns. have conjectured abOut lhe,r lwofold: ftrstly. the ltmestone IS ollen down the centre. Frgures drawn m orIgins and slgmflcance. naturally shaped mlO overhangs which profile have lhe head. more olten than prOVided protection from wmd and ram not. laCing the YleWers fight. Only rarely In the late 1940'$lhearllsl Thee Schoon for both the arllsts and Ihelr artwork; are drawmgs lruly reallsllc: moslly the began 10 observe and record Ihe rock and secondly, the I1ghl-coloured shapes are stylized. -

Coastal Water Quality in Selected Bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 - 2007

Coastal water quality in selected bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 - 2007 Report R08/52 ISBN 978-1-86937-848-6 Lesley Bolton-Ritchie June 2008 Report R08/52 ISBN 978-1-86937-848-6 58 Kilmore Street PO Box 345 Christchurch Phone (03) 365 3828 Fax (03) 365 3194 75 Church Street PO Box 550 Timaru Phone (03) 688 9069 Fax (03) 688 9067 Website: www.ecan.govt.nz Customer Services Phone 0800 324 636 Coastal water quality in selected bays of Banks Peninsula 2001 – 2007 Executive Summary This report presents and interprets water quality data collected by Environment Canterbury in selected bays of Banks Peninsula over two time periods: November 2001-June 2002 and July 2006-June 2007. Over 2001- 2002 the concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus based determinands (nutrients) were measured while over 2006-2007 the concentrations of nutrients, chlorophyll-a, total suspended solids, enterococci, and salinity were measured. The bays sampled were primarily selected to represent a range of geographic locations around the peninsula. These bays varied in regard to aspect of the entrance, length, width and land use. The bays sampled over both time periods were Pigeon Bay, Little Akaloa, Okains Bay, Le Bons Bay, Otanerito and Flea Bay. Hickory Bay and Te Oka Bay were also sampled over 2001-2002 but not over 2006-2007 while Port Levy and Tumbledown Bay were sampled over 2006-2007 but not over 2001-2002. Median concentrations of the nutrients ammonia nitrogen (NH3N), nitrate-nitrite nitrogen (NNN), total nitrogen (TN), dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) and total phosphorus (TP) were typically comparable to those reported from sites north and south of Banks Peninsula but some differed from those in Akaroa and Lyttelton harbours.