West Donegal Resource Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 2.3

Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 2.3 DEPLOYMENT REQUIREMENTS MHC-22673847-3 Redaction Version Schedule 2.3 (Deployment Requirements) 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Schedule sets out the deployment requirements. Its purpose is to set out the minimum requirements with which NBPco must comply with respect to the deployment of the Network. 2 SERVICE REQUIREMENTS 2.1 NBPco is required throughout the Contract Period to satisfy and comply with all the requirements and descriptions set out in, and all other aspects of, this Schedule. 3 GENERAL NBPCO OBLIGATIONS 3.1 Without limiting or affecting any other provision of this Agreement, in addition to its obligations set out in Clause 14 (Network Deployment, Operation and Maintenance) and the requirements for Network Deployment set out in Paragraph 8 (Network Deployment – Requirements) of this Schedule and elsewhere in this Agreement, NBPco shall: 3.1.1 perform Network Deployment in accordance with the Implementation Programme, the Wholesale Product Launch Project Plan, the Network Deployment Plan, the Operational Environment Project Plan and the Service Provider Engagement Framework Project Plan so as to Achieve each Milestone by the associated Milestone Date; 3.1.2 perform such activities, tasks, functions, works and services as are necessary to perform Network Deployment in accordance with the Implementation Programme, the Wholesale Product Launch Project Plan, the Network Deployment Plan, the Operational Environment Project Plan and the Service Provider Engagement Framework Project -

Donegal YOUTHREACH News

June 2014 Donegal ETB Donegal ETB W EEE ’’’ R EREE O NONN T H E W E BEBB !!! Volume 12, Issue 2 WWW ... DONEGAL ETB. I EIEE /// YOUTHREACH YOUTHREACH County Coordinator 24 Millfield Heights, Buncrana WWW ... YOUTHREACH ... I EIEE Donegal YOUTHREACH Co Donegal Tel/Fax: 074 93 20908 Youthreach is funded by Email: [email protected] TTT W I TT ER : @ D O N E G A L Y RYRR SOLAS & the European Social Fund News Gortahork Youthreach Participate in Activat8 Project Welcome... to the second edition of our 2014 newsletter and the last one Inside this issue: before the summer holidays at the end of July. The last few months have been as busy as ever for the Youthreach programme in Co Donegal: further Peace III Lifford: The Inside 2 Story funding has been received for the Restorative Practices project which centre learners, staff and parents continue to work on, while health promotion has Ballyshannon’s 2 Library Visit been the focus of some centres during the month of April. Letterkenny Win ETB 2 We’ve continued to build our Twitter account as well—you Award for Health can follow us @DonegalYR. The next edition of the Youthreach Gortahork and The Yard Youth project recently undertook some Buncrana Gets Active 3 newsletter will be available in the autumn. action research exploring the reality of life for young people who have left Dr Sandra Buchanan, Youthreach County Coordinator school and are trying to do something with their lives. This project involved Activat8 in Gortahork 4 the Yard team workers organising meetings for young people in Youthreach and at the Yard to help them explore their story of school, exams, unemployment and their future. -

Civil Registrations of Deaths in Ireland, 1864Ff — Elderly Rose

Civil Registrations of Deaths in Ireland, 1864ff — Elderly Rose individuals in County Donegal, listed in birth order; Compared to Entries in Griffith's Valuation for the civil parish of Inver, county Donegal, 1857. By Alison Kilpatrick (Ontario, Canada) ©2020. Objective: To scan the Irish civil records for deaths of individuals, surname: Rose, whose names appear to have been recorded in Griffith's Valuation of the parish of Inver, county Donegal; and to consult other records in order to attempt reconstruction of marital and filial relationships on the off chance that descendants can make reliable connections to an individual named in Griffith's Valuation. These other records include the civil registrations of births and marriages, the Irish census records, historical Irish newspapers, and finding aids provided by genealogical data firms. Scope: (1) Griffith's Valuation for the parish of Inver, county Donegal, 1857. (2) The civil records of death from 1864 forward for the Supervisor's Registration District (SRD) of Donegal were the primary focus. Other SRDs within and adjacent to the county were also searched, i.e., Ballyshannon, Donegal, Dunfanaghy, Glenties, Inishowen, Letterkenny, Londonderry, Millford, Strabane, and Stranorlar. Limitations of this survey: (i) First and foremost, this survey is not a comprehensive one-name study of the Rose families of county Donegal. The purpose of this survey was to attempt to answer one specific question, for which:—see "Objective" above. (ii) The primary constraints on interpreting results of this survey are the absence of church and civil records until the 1860s, and the lack of continuity between the existing records. -

1. Aquaculture Production Business 2. Reg No. FHA 3. Geographical

1. Aquaculture Production Business 2. Reg 3. Geographical 4. Species Kept 5. Recognised Health Status 6. Farm Type 7. Farm No. FHA Position Production Production Area 4.1 Species 4.1.1 4.1.2 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kept Marteilia Bonamia Marteilia Bonamia OsHV-1 Refringens Ostrea Refringens Ostrea Name of the Aquaculture production Aquaculture Name of the farm business / of the farm location Address or Number Registration for each degrees) Longitude (decimal production area for each degrees) Latitude (decimal production area species or vector No, Susceptible present Yes, Susceptible species present Yes, vector species present species or vector No, Susceptible present Yes, Susceptible species present Yes, vector species present 5.1.1.1 Declared disease free 5.1.1.2 Under Surveillance programme 5.1.1.3 Not known to be infected 5.1.1.4 Other 5.1.2.1 Declared disease free 5.1.2.2 Under Surveillance programme 5.1.2.3 Not known to be infected 5.1.2.4 Other 5.1.3.1 Declared disease free 5.1.3.2 Under Surveillance programme 5.1.3.3 Not known to be infected 5.1.3.4 Other 6.1.1 Mollusc farm open 6.1.2 Mollusc farm closed (recirculation) 6.1.3 Dispatch Centre, purification centre 6.1.4 Mollusc farming area 6.1.5 Research facility 6.1.6 Quarantine Facility 6.1.7 Other 7.1.1 Hatchery 7.1.2 Nursery 7.1.4 Grow out for human consumption 7.1.6 Other Farm A McCarthy Mussels Ltd (Carlingford Carlingford Lough, Co. -

MINUTES of MEETING of ISLANDS COMMITTEE HELD on 13Th

MINUTES OF MEETING OF ISLANDS COMMITTEE HELD ON 13th FEBRUARY 2018 IN DUNGLOE PUBLIC SERVICES CENTRE ___________________________________________________________ MEMBERS PRESENT: Cllr. Michéal Cholm Mac Giolla Easbuig Cllr. John Sheamais Ó Fearraigh Cllr. Enda Bonner Cllr. Marie Therese Gallagher Diarmuid Ó Mórdha William Boyle Eamonn Bonner Seán Ó Brían Séamus Mac Ruairí Mairín Uí Fhearraigh Rosaleen McShane Eamonn S Mac Aoidh OFFICIALS PRESENT: Michael McGarvey – Director of Water Service Eamonn Brown-A/Area Manager, Housing & Corporate Dermot Brady – Senior Assistant Fire Chief Officer Charles Sweeney – Area Manager, Community Development Brendan McFadden-S.E.E, Area Manager, Roads Service John Hegarty-Executive Engineer, Roads Service Fiona Kelly – A/Administrative Officer, Environment Michael Rowsome-S.S.O, Corporate & Motor Tax APOLOGIES: Cllr. Terence Slowey Cllr. Seamus Ó Domhnaill Cllr. Ian McGarvey Cathal Mac Suibhne – Marine Engineer Máire Uí Dhochartaigh Noirín Uí Mhaoldomhnaigh David Friel Marjorie Uí Chearbhaill IC 01/18 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON 10TH OCTOBER 2017 On the proposal of Seamus Rodgers, seconded by William Boyle, the minutes of meeting held on 10th October 2017 were confirmed subject to the following amendments: 1.1 County Roads on Arranmore IC34.10 “On the proposal of Noirín Uí Mhaoldomhnaigh, seconded by Cllr. Bonner, the Committee requested the inclusion of the following roads on the Island priority list in relation to Arranmore – (County Roads) (i) Road from children’s playground to property of Madge Boyle at Bun an Fhid. (ii) Road from Chris Gaughan’s to property of Mary Early at Cloch Corr. (iii) Road from Cross Roads at Illion, property of Tessie Ward to property of Frances Early, Upper Illion and (link roads). -

The Freedom of a Road Trip the Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland Is One of the Most Scenic Coastal Roads in the World

newsroom Scene and Passion Jul 18, 2019 The freedom of a road trip The Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland is one of the most scenic coastal roads in the world. German travel blogger Sebastian Canaves from “Off the Path” visited this magical place with the Porsche 718 Cayman GTS. “Road trips are the ultimate form of travel — complete freedom,” says Sebastian Canaves. His eyes sweep over the almost endless rich green of Ireland, the steep cliffs and finally out to the open sea. A stiff breeze blows into the face of the travel blogger, who is exploring the Wild Atlantic Way in Ireland together with his partner Line Dubois and the Porsche 718 Cayman GTS. Sebastian Canaves has travelled the world. He has already seen all the continents of this earth, visited more than 100 countries, and runs one of the most successful travel blogs in Europe with “Off the Path”. And yet, at this moment, you can feel how impressed he is by the natural force of Ireland and the ever-present expanse of the country. “This is one of the most spectacular and beautiful road trips I know,” says the outdoor expert. He is referring to the Wild Atlantic Way. More than 2,600 km in length, this is one of the longest and oldest defined coastal roads in the world. From the far north and the sleepy villages of Donegal to the small coastal town of Kinsale in the south of County Cork, the road hugs the coast directly next to the ocean. “A new adventure awaits around every corner,” says Canaves. -

On a Rock in the Middle of the Ocean Songs and Singers in Tory Island, Ireland

05-233 01 Front.qxd 8/24/05 9:34 PM Page iii On a Rock in the Middle of the Ocean Songs and Singers in Tory Island, Ireland Lillus Ó Laoire in collaboration with Éamonn Mac Ruairí, Belle Mhic Ruairí, Teresa McClafferty, Séamas Ó Dúgáin, Gráinne Uí Dhúgáin, and John Ó Duibheannaigh Europea: Ethnomusicologies and Modernities, No. 4 THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford 2005 05-233 01 Front.qxd 8/24/05 9:34 PM Page v Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction Tory Island Songs and Singers xi Chapter 1 Foundations: Toward an Ethnography 1 Chapter 2 Ethnography: Practice and Theory 23 Chapter 3 Lifting and Learning 43 Chapter 4 The Mechanics of the Aesthetic 89 Chapter 5 Performance of Song in Tory 125 Chapter 6 The Emotional Matrix of Dance and Song 157 Chapter 7 The Meaning of Song: An Interpretive Case Study 183 Chapter 8 Song: Play, Performance, and Tragedy 233 Chapter 9 Laughter and Tears 257 Chapter 10 On a Rock in the Middle of the Ocean 283 Appendix A: Music Sheet for Song by F. J. Farron 287 v 05-233 01 Front.qxd 8/24/05 9:34 PM Page vi vi Contents Appendix B: Compact Disc Tracks with Song Lyrics 293 Appendix C: List of Compact Disc Tracks with Timings 327 Bibliography 329 Index 347 05-233 01 Front.qxd 8/24/05 9:34 PM Page vii Acknowledgments Many debts are incurred during the course of writing a work of this kind, which are a pleasant duty to acknowledge here. -

Sliabh Liag Peninsula / Slí Cholmcille

SLIABH LIAG PENINSULA / SLÍ CHOLMCILLE www.hikingeurope.net THE ROUTE: ABOUT: A scenic coastal hike along the Wild Atlantic Way taking in local culture and This tour is based around the spectacular coast between the towns of history Killybegs and Ardara in County Donegal. The area is home to Sliabh Liag HIGHLIGHT OF THE ROUTE: (Slieve League) one of the highest sea cliffs in Europe and also a key signature discovery point along the Wild Atlantic Way. The breathtaking Experience the spectacular views from one of Europe’s highest sea cliffs at views at Sliabh Liag rightly draw visitors from all four corners of the globe. Sliabh Liag Unlike most, who fail to stray far from the roads, you get the chance to see SCHEMATIC TRAIL MAP: the cliffs in all their glory. The walk follows the cliffs from the viewing point at Bunglass to the ruins of the early-Christian monastery of Saint Aodh McBricne. The views from around the monastery are simply jaw dropping, with the great sweep of land to the east and the ocean far below to the west. The tour follows much of “Slí Cholmcille” part of the Bealach Na Gaeltachta routes and takes in the village of Glencolmcille where wonderful coastal views across the bay to Glen head await and a number of pre and early- Christine sites in the valley can be visited. The route concludes in Ardara, a centre renowned for traditional Irish music and dance, local festivals and numerous bars and restaurants. NAME OF THE ROUTE: Sliabh Liag / Sli Cholmcille leaving the road to cross a low hill to take you to your overnight destination overlooking Donegal Bay. -

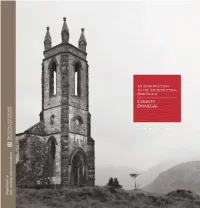

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

Killybegs Harbour Centre & South West Donegal, Ireland Access To

Killybegs Harbour Centre & South West Donegal, Ireland Area Information Killybegs is situated on the North West Coast of Ireland with the newest harbour facility in the country which opened in 2004. The area around the deep fjord-like inlet of Killybegs has been inhabited since prehistoric times. The town was named in early Christian times, the Gaelic name Na Cealla Beaga referring to a group of monastic cells. Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly in a region not short of native saints, the town’s patron saint is St. Catherine of Alexandria. St. Catherine is the patron of seafarers and the association with Killybegs is thought to be from the 15th Century which confirms that Killybeg’s tradition of seafaring is very old indeed. The area is rich in cultural & historical history having a long association with marine history dating back to the Spanish Armada. Donegal is renowned for the friendliness & hospitality of its people and that renowned ‘Donegal Welcome’ awaits cruise passengers & crew to the area from where a pleasant travel distance through amazing sea & mountain scenery of traditional picturesque villages with thatched cottages takes you to visit spectacular castles and national parks. Enjoy the slow pace of life for a day while having all the modern facilities of city life. Access to the area Air access Regular flights are available from UK airports and many European destinations to Donegal Airport which is approx an hour’s drive from Killybegs City of Derry Airport approx 1 hour 20 mins drive from Kilybegs International flights available to and from Knock International Airport 2 hours and 20 minutes drive with public transport connections. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

Natura Impact Assessment : for Algaran, Cashelings, Kilcar, Co, Donegal

Natura Impact Assessment : for Algaran, Cashelings, Kilcar, Co, Donegal. Natura Impact Appropriate Assessment and Statement As part of the “Fore shore Licence Application to the Department of Environment, Community and Local Government. Ref: MS51/15/695 For the Continuation of Sustainable Sea Algae Harvesting by Algaran, at Muckross Head, Kilcar ( Donegal Bay) Co. Donegal. March 3rd 2014 Applicant: Algaran Ms Rosaria Piseria and Mr Michael Mccloskey Cashlings Kilcar Donegal Co. Donegal. EU Natura Report by Catherine Storey CEnv, MIEnvSc, MCIEEM Upper Kilraine Glenties Co. Donegal T. 0719300591 M. 0861201432 E. [email protected] 1 Algaran, Natura Impact Assessment for Foreshore Licence March 2014 Map 1. Site location marked with red dot. Ordnance Survey of Ireland License no. EN 0031014©Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland. This map has been extracted and compiled by Catherine Storey CEnv MIEnvSc MCIEEM from www.npws.ie and www. myplan.ie Algaran, Natura Impact Assessment for Foreshore Licence March 2014 Map two. Site Location of sea weed harvesting.. Total distance of 3.52Km of foreshore, outlined in Blue. Scale 1:50000. Ordnance Survey of Ireland License no. EN 0031014©Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland. This map has been extracted and compiled by Catherine Storey CEnv MIEnvSc MCIEEM from www.npws.ie and www. myplan.ie Algaran, Natura Impact Assessment for Foreshore Licence March 2014 Map 3. Access to site via road. Map scale 1:10000 Ordnance Survey of Ireland License no. EN 0031014©Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland. This map has been extracted and compiled by Catherine Storey CEnv MIEnvSc MCIEEM from www.npws.ie and www.