Doctor by Nature Lookinside.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices and Proceedings: West of England: 27 May 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2504 PUBLICATION DATE: 27 May 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 17 June 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 10/06/2014 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All post relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Jubilee House Croydon Street Bristol BS5 0DA The public counter at the Bristol office is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

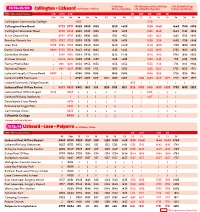

Liskeard • Looe • Polperro Callington • Liskeard Via Pensilva

S: Saturdays SSH: Saturdays and School Holidays coHS: Callywith College 73/73A/74/174 Callington • Liskeard via Pensilva - St Cleer SD: Schooldays Only coD: Callywith College Days Holidays and Saturdays MON to SAT except Bank Holidays coD coHS coD SD SSH SD SSH SD 74 A 174 174 74 74 74 73 74 74 73 73 74 74 74 74 74 74 Callington Community College 0815 1510 Callington New Road 0735 0735 0820 0920 1020 122 0 14 20 1520 154 0 16 4 0 174 0 183 0 Callington Westover Road 0738 0738 0823 0923 1023 1223 1423 1523 1543 1643 174 3 1833 St Ive Church End 0747 0747 0832 0932 1032 1232 1432 1532 1552 1652 1752 1842 Pensilva Victoria Inn 0750 0753 0753 0838 0938 1038 123 8 1438 1538 1558 1658 175 8 184 8 Glen Park 0758 0755 0755 0840 0940 104 0 124 0 1440 154 0 16 0 0 170 0 180 0 1850 Darite Crows Nest Inn 0800 0758 0758 0843 0943 1043 124 3 14 43 1543 16 03 1703 1803 1853 Darite Bus Shelter $ 0801 0801 0846 0946 104 6 124 6 14 4 6 154 6 16 06 170 6 1806 1856 St Cleer Church $ 0808 0808 0853 0953 1053 1253 14 53 1553 1613 1713 1813 19 03 Tremar Phone Box $ 0 8 11 0 8 11 0856 0956 1056 125 6 14 56 1556 1616 1716 1816 19 0 6 Trevecca/Depot $ 0 817 0 817 0902 10 02 11 0 2 13 0 2 1502 16 02 1622 1722 1822 1912 Liskeard Hospital Clemo Road 0809 $ $ 0906 10 06 11 0 6 13 0 6 1506 16 06 1626 1726 1826 1916 Liskeard A390 Morrisons $ $ $ 0909 10 09 11 0 9 1215 13 0 9 1509 1530 16 09 1629 1629 1729 1829 1919 Liskeard Community College Grounds $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 1525 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Liskeard Post Office Arrive $ 0823 0823 0 915 1015 1115 122 0 1315 1515 1528 1535 -

Recording the Manx Shearwater

RECORDING THE MANX There Kennedy and Doctor Blair, SHEARWATER Tall Alan and John stout There Min and Joan and Sammy eke Being an account of Dr. Ludwig Koch's And Knocks stood all about. adventures in the Isles of Scilly in the year of our Lord nineteen “ Rest, Ludwig, rest," the doctor said, hundred and fifty one, in the month of But Ludwig he said "NO! " June. This weather fine I dare not waste, To Annet I will go. This very night I'll records make, (If so the birds are there), Of Shearwaters* beneath the sod And also in the air." So straight to Annet's shores they sped And straight their task began As with a will they set ashore Each package and each man Then man—and woman—bent their backs And struggled up the rock To where his apparatus was Set up by Ludwig Koch. And some the heavy gear lugged up And some the line deployed, Until the arduous task was done And microphone employed. Then Ludwig to St. Agnes hied His hostess fair to greet; And others to St. Mary's went To get a bite to eat. Bold Ludwig Koch from London came, That night to Annet back they came, He travelled day and night And none dared utter word Till with his gear on Mary's Quay While Ludwig sought to test his set At last he did alight. Whereon he would record. There met him many an ardent swain Alas! A heavy dew had drenched To lend a helping hand; The cable laid with care, And after lunch they gathered round, But with a will the helpers stout A keen if motley band. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall a Wonderful Home Full of Character with Superb Sea Views and Easy Access to the Village

Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall Polperro House Polperro, Cornwall A wonderful home full of character with superb sea views and easy access to the village. Fowey 7 miles, Eden Project 18 miles, Plymouth 25 miles (All distances are approximate) Accommodation and amenities Entrance hall | Living room | Kitchen/Dining room | WC Principal Bedroom | Four further bedrooms | Reception room Two Bathrooms | Shower room | WC About XXXX acres Exeter 19 Southernhay East, Exeter EX1 1QD Tel: 01392 423111 [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Polperro is a village and fishing port originally belonging to the ancient Raphael Manor mentioned in the Doomsday Book. Situated on the River Pol, four miles west of the major resort of Looe and 25 miles west of the major city and port of Plymouth, it has a picturesque fishing harbour lined with tightly packed houses which make it a popular tourist location in the summer months. The village retains almost all of its 17th Century architectural charm and has been a working fishing port since the 13th Century. This peaceful fishing cove was once a thriving centre for the area's smuggling. Today, in cellars where furtive smugglers once dodged the Customs Officer’s muskets, you can see displays of local crafts and fishermen's smocks, or dine in style at one of Polperro's excellent restaurants. Fishing trips or pleasure cruises can be arranged from the quayside, or one can take the cliff path to explore the secluded smuggling coves of Talland and Lantivet Bay. With its protected inner harbour full of colourful boats packed tightly into a steep valley on either side of the River Pol, the quaint colour-washed cottages and twisting streets, Polperro offers surprises at every turn: the Saxon and Roman bridges, the famous House on Props, The Old Watch House, the fish quay, and the 16th Century house where Dr. -

Liskeard • Looe • Polperro Callington • Liskeard Via Pensilva

SH: School Holidays Only COLL - Callywith SD: School Days Only 73/73A/74/174 via Pensilva - St Cleer NS: Not Saturdays Callington • Liskeard College Days Only SSH: Saturdays and School Holidays Only SNC: Saturday Not College Days MON to SAT except Bank Holidays SNC COLL SSH SD SD SSH SD SSH SD 73A 174 174 74 74 74 74 73 74 74 73 73 74 74 74 74 74 74 Callington Community College 0 817 1510 Callington New Road 0735 0735 0820 0820 0920 1020 122 0 14 20 1520 154 0 16 4 0 174 0 183 0 Callington Westover Road 0738 0738 0823 0823 0923 1023 1223 1423 1523 1543 1643 174 3 1833 St Ive Church End 0747 0747 0832 0832 0932 1032 1232 1432 1532 1552 1652 1752 1842 Pensilva Victoria Inn 0753 0753 0838 0838 0938 1038 123 8 1438 1538 1558 1658 175 8 184 8 Glen Park 0755 0755 0840 0840 0940 104 0 124 0 1440 154 0 16 0 0 170 0 180 0 1850 Darite Crows Nest 0758 0758 0843 0843 0943 1043 124 3 14 43 1543 16 03 1703 1803 1853 Darite Bus Shelter 0801 0801 0846 0846 0946 104 6 124 6 14 4 6 154 6 16 06 170 6 1806 1856 St Cleer Church 0808 0808 0853 0853 0953 1053 1253 14 53 1553 1613 1713 1813 19 03 Tremar Phone Box 0 8 11 0 8 11 0856 0856 0956 1056 125 6 14 56 1556 1616 1716 1816 19 0 6 Trevecca/Depot 0 817 0 817 0902 0902 10 02 11 0 2 13 0 2 1502 16 02 1622 1722 1822 1912 Liskeard Hospital Clemo Road $ $ 0906 0906 10 06 11 0 6 13 0 6 1506 16 06 1626 1626 1726 1826 1916 Liskeard Morrisons A390 $ $ 0909 0909 10 09 11 0 9 1215 13 0 9 1509 1530 16 09 1629 1629 1729 1829 1919 Liskeard Sch & Community College [Sch Grounds] $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 1525 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Liskeard -

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway Via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash COVID 19 Mondays to Saturdays Route 11 towards Bodmin Route 11 towards Plymouth Plymouth Royal Parade (A7) 0835 1035 1235 1435 1635 1835 1935 Bodmin Parkway Station 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2010 Railway Station Saltash Road 0839 1039 1239 1439 1639 1839 1939 Trago Mills 1020 1220 1420 1620 Milehouse Alma Road 0842 1042 1242 1442 1642 1842 1942 Dobwalls Methodist Church 1027 1227 1427 1627 1823 2023 St Budeaux Square [S1] 0850 1050 1250 1450 1650 1849 1949 Liskeard Lloyds Bank 0740 0840 1040 1240 1440 1640 1840 2032 Saltash Fore Street 0855 1055 1255 1455 1655 1854 1954 Liskeard Dental Centre 0741 0841 1041 1241 1441 1641 1841 Callington Road shops 0858 1058 1258 1458 1658 1857 1957 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0744 0844 1044 1244 1444 1644 1844 Burraton Plough Green 0900 1100 1300 1500 1700 1859 1959 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0748 0848 1048 1248 1448 1648 1848 Landrake footbridge 0905 1105 1305 1505 1705 1904 2004 Trerulefoot Garage 0751 0851 1051 1251 1451 1651 1851 Tideford Quay Road 0908 1108 1308 1508 1708 1907 2007 Tideford Brick Shelter 0754 0854 1054 1254 1454 1654 1854 Trerulefoot Garage 0911 1111 1311 1511 1712 1910 2010 Landrake footbridge 0757 0857 1057 1257 1457 1657 1857 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0914 1114 1314 1514 1715 1913 2013 Burraton Ploughboy 0802 0902 1102 1302 1502 1702 1902 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0919 1119 1319 1519 1720 1918 2018 Callington Road shops 0804 0904 1104 1304 1504 1704 1904 Liskeard Dental Centre 0921 1121 1321 1521 -

Visit Cornwall

Visit CornwallThe Official Destination & Accommodation Guide for 2014 www.visitcornwall.com 18 All Cornwall Activities and Family Holiday – Attractions Family Holiday – Attractions BodminAll Cornwall Moor 193 A BRAVE NEW World Heritage Site Gateway SEE heartlands CORNWALL TAKE OFF!FROM THE AIR PREPARE FOR ALL WEATHER MUSEUM VENUE South West Lakes PLEASURE FLIGHTS: SCENIC OR AEROBATIC! Fun for all the family CINEMA & ART GALLERY Escape to the country for a variety of great activities... RED ARROWS SIMULATORCome and see our unique collection of historic, rare and many camping • archery • climbing Discover World Heritage Site Exhibitions still flyable aircraft housed inside Cornwall’s largest building sailing • windsurfi ng • canoeing Explore beautiful botanical gardens wakeboarding rowing fi shing Indulge at the Red River Café • • THE LIVING AIRCRAFT MUSEUM WHERE HISTORY STILL FLIES GIFT SHOPCAFECHILdren’s areA cycling • walking • segway adventures Marvel at inspirational arts, crafts & creativity ...or just relax in our tea rooms Go wild in the biggest adventure playground in Cornwall Hangar 404, Aerohub 1, Tamar Lakes Stithians Lake Siblyback Lake Roadford Lake Newquay Cornwall Airport, TR8 4HP near Bude near Falmouth near Liskeard near Launceston heartlandscornwall.com Just minutes off the A30 in Pool, nr Camborne. Sat Nav: TR15 3QY 01637 860717 www.classicairforce.com Call 01566 771930 for further details OPEN DAILY from 10am or visit www.swlakestrust.org.uk flights normally run from March-October weather permitting Join us in Falmouth for: • Tall ships & onboard visits • Day sails & boat trips • Crewing opportunities • Live music & entertainment • Exhibitions & displays • Children’s activities • Crew parade • Fireworks • Parade of sail & The Eden Project is described as the eighth wonder race start TAKE A WALK of the world. -

Polperro Looe Liskeard Pensilva Callington S S

s s s the s Polperro Looe Liskeard Pensilva Callington 573 for additional buses between Polperro and Looe, see times for the 572 Monday to Saturday buses 574 573 573 573 573 573 573 573 573 573 573 573 574 574 SSH SD SD Polperro Crumplehorn 0 6 5 8 0 743 0800 0855 0943 1043 43 1543 1643 1743 1813 1913 opp Killigarth Manor Turn 0703 0748 0805 0900 0948 1048 48 1548 1648 1748 1818 1918 opp Seaview Holiday Park 0704 0749 0806 0901 0949 1049 49 1549 1649 1749 1819 1919 Pelynt Church --- 0753 0810 --- 0953 1053 53 1540 1553 1653 1753 --- --- Trelay Farm Turn --- 0754 0811 --- 0954 1054 54 1541 1554 1654 1754 --- --- Caradon Camping for Trelawne Manor --- 0759 --- 0905 0959 1059 59 --- 1559 1659 1759 1823 1923 opp West Waylands Holiday Park 0705 0804 0815 0909 1003 1103 03 1543 1603 1703 1803 1827 1927 Oaklands Holiday Park 0706 0805 0816 0910 1004 1104 04 1544 1604 1704 1804 1828 1928 opp Tencreek Holiday Park Turn 0707 0806 0817 0911 1005 1105 05 1545 1605 1705 1805 1829 1929 West Looe Fire Station 0708 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 1838 1938 East Looe Bridge Surgery 0710 0810 0831 0916 1010 1110 10 1550 1610 1710 1810 1840 1940 Sandplace Station 0714 0814 0835 0920 1014 1114 14 1614 1714 1814 1844 1944 Duloe Shelter 0719 0819 0840 0925 1019 1119 19 1619 1719 1819 1849 1949 St Keyne Shelter 0725 0825 0846 0931 1025 1125 25 1625 1725 1825 1855 1955 opp Liskeard Station 0731 0831 0852 0937 1031 1131 31 1631 1731 1831 1901 2001 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ Liskeard Parade opp Post Office arr 0735 0835 0856 0941 1035 1135 35 16‘ 35 1735 1835 1905 -

PDF Timetable 73

Callington to Liskeard 74 via Pensilva | St CleerLooe Mondays to Saturdays except bank holidays Callington Community College 0815 1510 Callington New Road 0730 0730 0820 0820 0920 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1545 1645 1740 1830 Callington Westover Road 0733 0733 0823 0823 0923 1018 1118 1218 1318 1418 1518 1548 1648 1743 1833 St Ive Church End 0742 0742 0832 0832 0932 1027 1127 1227 1327 1427 1527 1557 1657 1752 1842 Upton Cross Post Box Pensilva Victoria Inn 0748 0748 0838 0838 0938 1033 1133 1233 1333 1433 1533 1603 1703 1758 1848 Glen Park 0750 0750 0840 0840 0940 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1605 1705 1800 1850 120 Darite Crows Nest Inn 0753 0753 0843 0843 0943 1038 1138 1238 1338 1438 1538 1608 1708 1803 1853 Darite Bus Shelter 0756 0756 0846 0846 0946 1041 1141 1241 1341 1441 1541 1611 1711 1806 1856 St Cleer Church 0803 0803 0853 0853 0953 1048 1148 1248 1348 1448 1548 1618 1718 1813 1903 Tremar phone box 0806 0806 0856 0856 0956 1051 1151 1251 1351 1451 1551 1621 1721 1816 1906 Trevecca/Depot 0812 0812 0902 0902 1002 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1557 1627 1727 1822 1912 Liskeard Hospital Clemo Road 0816 0906 0906 1006 1101 1201 1301 1401 1501 1601 1631 1731 1826 1916 Liskeard A390 opp Morrisons 0819 0909 0909 1009 1104 1204 1304 1404 1504 1604 1634 1634 1734 1829 1919 Liskeard Post Office 0819 0825 0915 0915 1015 1110 1210 1310 1410 1510 1610 1640 1640 1740 1835 1925 Liskeard Railway Station 1612 continues to Polperro as service 73 below with no need to change buses! 73 Liskeard to Polperro via St Keyne | Duloe | Looe | Trelawne -

NOTICE of POLL Notice Is Hereby Given That

Cornwall Council Election of a Unitary Councillor Altarnun Division NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Unitary Councillor for the Division of Altarnun will be held on Thursday 4 May 2017, between the hours of 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM 2. The Number of Unitary Councillors to be elected is One 3. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidates nomination papers are as follows: Name of Candidate Address Description Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper Peter Russell Tregrenna House The Conservative Anthony C Naylor Robert B Ashford HALL Altarnun Party Candidate Antony Naylor Penelope A Aldrich-Blake Launceston Avril M Young Edward D S Aldrich-Blake Cornwall Elizabeth M Ashford Louisa A Sandercock PL15 7SB James Ashford William T Wheeler Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Thomas L Hoskin Gus T Atkinson MAY Five Lanes Debra A Branch Jennifer C French Altarnun Daniel S Bettison Sheila Matcham Launceston Avril Wicks Patricia Morgan PL15 7RY Michelle C Duggan James C Sims Adrian Alan West Illand Farm Liberal Democrats Frances C Tippett William Pascoe PARSONS Congdons Shop Richard Schofield Anne E Moore Launceston Trudy M Bailey William J Medland Cornwall Edward L Bailey Philip J Medland PL15 7LS Joanna Cartwright Linda L Medland 4. The situation of the Polling Station(s) for the above election and the Local Government electors entitled to vote are as follows: Description of Persons entitled to Vote Situation of Polling Stations Polling Station No Local Government Electors whose names appear on the Register of Electors for the said Electoral Area for the current year.