Parramatta Girls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Sydney Theatre Award Nominations

2015 SYDNEY THEATRE AWARD NOMINATIONS MAINSTAGE BEST MAINSTAGE PRODUCTION Endgame (Sydney Theatre Company) Ivanov (Belvoir) The Present (Sydney Theatre Company) Suddenly Last Summer (Sydney Theatre Company) The Wizard of Oz (Belvoir) BEST DIRECTION Eamon Flack (Ivanov) Andrew Upton (Endgame) Kip Williams (Love and Information) Kip Williams (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE Paula Arundell (The Bleeding Tree) Cate Blanchett (The Present) Jacqueline McKenzie (Orlando) Eryn Jean Norvill (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE Colin Friels (Mortido) Ewen Leslie (Ivanov) Josh McConville (Hamlet) Hugo Weaving (Endgame) BEST ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Blazey Best (Ivanov) Jacqueline McKenzie (The Present) Susan Prior (The Present) Helen Thomson (Ivanov) BEST ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Matthew Backer (The Tempest) John Bell (Ivanov) John Howard (Ivanov) Barry Otto (Seventeen) BEST STAGE DESIGN Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) Renée Mulder (The Bleeding Tree) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) BEST COSTUME DESIGN Alice Babidge (Mother Courage and her Children) Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Alicia Clements (After Dinner) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) BEST LIGHTING DESIGN Paul Jackson (Love and Information) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) Nick Schlieper (King Lear) Emma Valente (The Wizard of Oz) BEST SCORE OR SOUND DESIGN Stefan Gregory (Suddenly Last Summer) Max Lyandvert (Endgame) Max Lyandvert (The Wizard of Oz) The Sweats (Love and Information) INDEPENDENT BEST INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION Cock (Red -

98Th ISPA Congress Melbourne Australia May 30 – June 4, 2016 Reimagining Contents

98th ISPA Congress MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA MAY 30 – JUNE 4, 2016 REIMAGINING CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE & COUNTRY 2 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, 3 STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMMING, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 7 LET THE COUNTDOWN BEGIN: A SHORT HISTORY OF ISPA 8 MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA 10 CONGRESS VENUES 11 TRANSPORT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 13 ISPA UP LATE 14 WHERE TO EAT & DRINK 15 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 16 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 18 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SPEAKERS 22 CONGRESS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 28 CONGRESS PERFORMANCES 37 CONGRESS AWARD WINNERS 42 CONGRESS SESSION SPEAKERS & MODERATORS 44 THE ISPA FELLOWSHIP CHALLENGE 56 2016 FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS 57 ISPA FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENTS 58 ISPA STAR MEMBERS 59 ISPA OUT ON THE TOWN SCHEDULE 60 SPONSOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 66 ISPA CREDITS 67 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE CREDITS 68 We are committed to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to become immersed in ISPA Melbourne. To help us make the most of your experience, please ask us about Access during the Congress. Cover image and all REIMAGINING images from Chunky Move’s AORTA (2013) / Photo: Jeff Busby ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR & COUNTRY CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, Arts Centre Melbourne respectfully acknowledges STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA the traditional owners and custodians of the land on Whether you’ve come from near or far, I welcome all which the 98th International Society for the Performing delegates to the 2016 ISPA Congress, to Australia’s Arts (ISPA) Congress is held, the Wurundjeri and creative state and to the world’s most liveable city. -

Visionsplendidfilmfest.Com

Australia’s only outback film festival visionsplendidfilmfest.comFor more information visit visionsplendidfilmfest.com Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival 2017 WELCOME TO OUTBACK HOLLYWOOD Welcome to Winton’s fourth annual Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival. This year we honour and celebrate Women in Film. The program includes the latest in Australian contemporary, award winning, classic and cult films inspired by the Australian outback. I invite you to join me at this very special Australian Film Festival as we experience films under the stars each evening in the Royal Open Air Theatre and by day at the Winton Shire Hall. Festival Patron, Actor, Mr Roy Billing OAM MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND MAJOR EVENTS THE HON KATE JONES MP It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Winton’s Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival, one of Queensland’s many great event experiences here in outback Queensland. Events like the Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival are vital to Queensland’s tourism prosperity, engaging visitors with the locals and the community, and creating memorable experiences. The Palaszczuk Government is proud to support this event through Tourism and Events Queensland’s Destination Events Program, which helps drive visitors to the destination, increase expenditure, support jobs and foster community pride. There is a story to tell in every Queensland event and I hope these stories help inspire you to experience more of what this great State has to offer. Congratulations to the event organisers and all those involved in delivering the outback film festival and I encourage you to take some time to explore the diverse visitor experiences in Outback Queensland. -

Seven Unveils Content Plans for 2019

SEVEN UNVEILS CONTENT PLANS FOR 2019 Slate includes new Bevan Lee drama and two supersized reality hits Geraldine Hakewill, Joel Jackson and Catherine McClements headline Miss Fisher spin-off MKR’s 10th anniversary season to launch the year “Top Gear meets food” in new Gordon Ramsay series New overseas dramas feature screen heavyweights Martin Clunes, Sheridan Smith, Kelsey Grammer and more (Sydney, Friday October 26): The Seven Network today unveiled its content plans for 2019. Four new local dramas, including the next offering from creator Bevan Lee; two supersized reality hits; a female spinoff to one of the year’s most heart-warming hits and the landmark 10th season of one of Australia’s biggest shows are just some of the programs set to take Seven into its 13th consecutive year of leadership. Commenting, Seven’s Director of Network Programming Angus Ross said: “After a close win last year, we promised to up our game in 2018, and the team has delivered in spades. We’ve broken records and dominated the ratings throughout the year. In fact, in every month we have never dropped below a 39% share, while our competitors have never been above 39%. Our worst is still better than their best. “What’s particularly pleasing is that this success is down to the strength and depth of our programming across the board. From 6am to midnight, we have the strongest spine of ratings winners, bar none. And with the AFL and Cricket locked up until 2022, Seven can guarantee those mass audiences, and certainty for our advertisers, for years to come.” NEW TO SEVEN IN 2019 BETWEEN TWO WORLDS From Australia’s most prolific creator/writer Bevan Lee (Packed to the Rafters, A Place To Call Home, All Saints, Winners & Losers, Always Greener) comes an intense, high concept contemporary drama series about two disparate and disconnected worlds, thrown together by death and a sacrifice in one and the chance for new life in the other. -

Annual Report 2013 Annual Report 2013

Annual Report 2013 Annual Report 2013 4 Objectives and Mission Statement 50 Open Door 6 Key Achievements 9 Board of Management 52 Literary 10 Chairman’s report Literary Director’s Report 12 Artistic Director’s report MTC is a department of the University of Melbourne 14 Executive Director’s report 54 Education 16 Government Support Education Manager’s Report and Sponsors 56 Education production – Beached 18 Patrons 58 Education Workshops and Participatory Events 20 2013 Mainstage Season MTC Headquarters 60 Neon: Festival of 252 Sturt St 22 The Other Place Independent Theatre Southbank VIC 3006 24 Constellations 03 8688 0900 26 Other Desert Cities 61 Daniel Schlusser Ensemble 28 True Minds 62 Fraught Outfit Southbank Theatre 30 One Man, Two Guvnors 63 The Hayloft Project 140 Southbank Blvd 32 Solomon and Marion 64 THE RABBLE Southbank VIC 3006 34 The Crucible 65 Sisters Grimm Box Office 03 8688 0800 36 The Cherry Orchard 66 NEON EXTRA 38 Rupert mtc.com.au 40 The Beast 68 Employment Venues 42 The Mountaintop Actors and Artists 2013 Throughout 2013 MTC performed its Melbourne season of plays at the 70 MTC Staff 2013 Southbank Theatre, The Sumner and The Lawler, 44 Add-on production and the Fairfax Studio and Playhouse at The Book of Everything 72 Financial Report Arts Centre Melbourne. 74 Key performance indicators 46 MTC on Tour: 76 Audit certificate Managing Editor Virginia Lovett Red 78 Financial Statement Graphic Designer Emma Wagstaff Cover Image Jeff Busby 48 Awards and nominations Production Photographers Jeff Busby, Heidrun Löhr Cover -

The 66Th Sydney Film Festival Begins 05/06/2019

MEDIA RELEASE: 9:00pm WEDNESDAY 5 JUNE 2019 THE 66TH SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL BEGINS The 66th Sydney Film Festival (5 – 16 June) opened tonight at the State Theatre with the World Premiere of Australian drama/comedy Palm Beach. Festival Director Nashen Moodley was pleased to open his eighth Festival to a packed auditorium including Palm Beach director Rachel Ward and producers Bryan Brown and Deborah Balderstone, alongside cast members Aaron Jefferies, Jacqueline McKenzie, Heather Mitchell, Sam Neill, Greta Scacchi, Claire van der Boom, and Frances Berry. Following an announcement of increased NSW Government funding by the Premier Gladys Berejiklian, Minister for the Arts Don Harwin commented, “Launching with Palm Beach is the perfect salute to great Australian filmmaking in a year that will showcase a bumper list of contemporary Australian stories, including 24 World Premieres.” “As one of the world’s longest-running film festivals, I’m delighted to build on our support for the Festival and Travelling Film Festival over the next four years with increased funding of over $5 million, and look forward to the exciting plans in store,” he said. Sydney Film Festival Board Chair, Deanne Weir said, “The Sydney Film Festival Board are thrilled and grateful to the New South Wales Government for this renewed and increased support. The government's commitment recognizes the ongoing success of the Festival as one of the great film festivals of the world; and the leading role New South Wales plays in the Australian film industry.” Lord Mayor of Sydney, Clover Moore also spoke, declaring the Festival open. “The Sydney Film Festival’s growth and evolution has reflected that of Sydney itself – giving us a window to other worlds, to enjoy new and different ways of thinking and being, and to reach a greater understanding of ourselves and our own place in the world.” “The City of Sydney is proud to continue our support for the Sydney Film Festival. -

Star-Studded Line-Up Set for the 7Th AACTA Awards Presented by Foxtel

Media Release Strictly embargoed until 12:01am Wednesday 22 November 2017 Star-studded line-up set for the 7th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel The Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) has today announced the star-studded line- up of presenters and attendees of the 7th AACTA Awards Ceremony presented by Foxtel. Held at The Star Event Centre in Sydney on Wednesday 6 December and telecast on Channel 7, tickets are still available to enjoy a night of glamour and entertainment with the country’s biggest stars. Tickets are open to the public and industry and are selling fast. To book, visit www.aacta.org. The Ceremony will see some of Australia’s top film and television talent take to the stage to present, including: Jessica Marais, Rachel Griffiths, Bryan Brown, Charlie Pickering, Noni Hazlehurst, Shane Jacobson, Sophie Monk, Rob Collins, Samara Weaving, Daniel MacPherson, Tom Gleeson, Erik Thomson, Melina Vidler, Ryan Corr, Dan Wyllie and celebrated Indian actor and member of the Best Asian Film Grand Jury Anupam Kher. Nominees announced as presenters today include: Celia Pacquola, Pamela Rabe, Marta Dusseldorp, Stephen Curry, Emma Booth, Osamah Sami, Ewen Leslie and Sean Keenan. A number of Australia’s rising stars will also present at the AACTA Awards Ceremony, including: Angourie Rice, Nicholas Hamilton, Madeline Madden, and stars of the upcoming remake of STORM BOY, Finn Little and Morgana Davies. Last year’s Longford Lyell recipient Paul Hogan will attend the Ceremony alongside a number of this year’s nominees, including: Anthony LaPaglia, Shaynna Blaze, Luke McGregor, Don Hany, Jack Thompson, Kate McLennan, Sara West, Matt Nable, Jacqueline McKenzie and Susie Porter. -

Company B ANNUAL REPORT 2008

company b ANNUAL REPORT 2008 A contents Company B SToRy ............................................ 2 Key peRFoRmanCe inDiCaToRS ...................... 30 CoRe ValueS, pRinCipleS & miSSion ............... 3 FinanCial Report ......................................... 32 ChaiR’S Report ............................................... 4 DiReCToRS’ Report ................................... 32 ArtistiC DiReCToR’S Report ........................... 6 DiReCToRS’ DeClaRaTion ........................... 34 GeneRal manaGeR’S Report .......................... 8 inCome STaTemenT .................................... 35 Company B STaFF ........................................... 10 BalanCe SheeT .......................................... 36 SeaSon 2008 .................................................. 11 CaSh Flow STaTemenT .............................. 37 TouRinG ........................................................ 20 STaTemenT oF ChanGeS in equiTy ............ 37 B ShaRp ......................................................... 22 noTeS To The FinanCial STaTements ....... 38 eDuCaTion ..................................................... 24 inDepenDenT auDiT DeClaRaTion CReaTiVe & aRTiSTiC DeVelopmenT ............... 26 & Report ...................................................... 49 CommuniTy AcceSS & awards ...................... 27 DonoRS, partneRS & GoVeRnmenT SupporteRS ............................ 28 1 the company b story Company B sprang into being out of the unique action taken to save Landmark productions like Cloudstreet, The Judas -

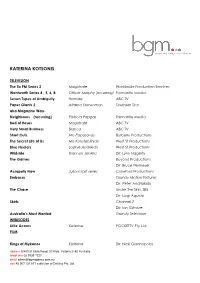

Katerina Kotsonis

KATERINA KOTSONIS TELEVISION The Ex PM Series 2 Magistrate Worldwide Production Services Wentworth Series 4 , 5, 6, 8 Officer Murphy (recurring) Fremantle Media Seven Types of Ambiguity Hamide ABC TV Paper Giants 2 Athena Starwoman Southern Star aka Magazine Wars Neighbours (recurring) Patricia Pappas Fremantle Media Bed of Roses Magistrate ABC TV Very Small Business Blanca ABC TV Short Cuts Mrs Papasavas Burberry Productions The Secret Life of Us Mrs Konstantinidis West St Productions Blue Heelers Sophie Andrikidis West St Productions Wildside Gannon Jenkins Dir: Lynn Hagerty The Games Beyond Productions Dir: Bruce Permezel Acropolis Now Julia in last series Crawford Productions Embassy Grundy Motion Pictures Dir: Peter Andriakidis The Chase Under the Skin, SBS Dir: Luigi Aquisto Skirts Channel 7 Dir: Ian Gilmore Australia’s Most Wanted Grundy Television WEBISODES Little Acorns Katerina POCKETTV Pty Ltd FILM Kings of Mykonos Katerina Dir: Nick Giannopolos address 5/400 St Kilda Road, St Kilda, Victoria 3182 Australia telephone 03 9939 7227 email [email protected] abn 45 007 137 671 a division of Deisfay Pty. Ltd. Cop Hard Ticket Lady Ep 6: Hades Undecover Surviving Georgia Angela Dir: Sandra Scriberras Waiting at the Royal Irene Apollo Films Head On Ariadne Great Scott Productions Dir: Ana Kokkinos Ralph Bambi Silo Productions Dir: Vincenzo Gallo SHORT FILMS Thicker Than Water 2011 The Rat 2011 Mayan Calendar 2011 Slap in the Face 2011 Word of Mouth 2011 Where the Heart Is 2011 THEATRE Emilia (Workshop) Margaret Johnson/ Essential Theatre Mary Sidney/Hester Happy Ending Script Workshop Milena Melbourne Theatre Company The House of King Auspicious Arts Projects All About My Mother Melbourne Theatre Co. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

National Theatre

WITH EMMA BEATTIE OLIVER BOOT CRYSTAL CONDIE EMMA-JANE GOODWIN JULIE HALE JOSHUA JENKINS BRUCE MCGREGOR DAVID MICHAELS DEBRA MICHAELS SAM NEWTON AMANDA POSENER JOE RISING KIERAN GARLAND MATT WILMAN DANIELLE YOUNG 11 JAN – 25 FEB 2018 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE Presented by Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne This production runs for approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes, including a 20 minute interval. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is presented with kind permission of Warner Bros. Entertainment. World premiere: The National Theatre’s Cottesloe Theatre, 2 August 2012; at the Apollo Theatre from 1 March 2013; at the Gielgud Theatre from 24 June 2014; UK tour from 21 January 2017; international tour from 20 September 2017 Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne acknowledge the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which this performance takes place, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors past and present, and to our shared future. DIRECTOR MARIANNE ELLIOTT DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER VIDEO DESIGNER BUNNY CHRISTIE PAULE CONSTABLE FINN ROSS MOVEMENT DIRECTORS MUSIC SOUND DESIGNER SCOTT GRAHAM AND ADRIAN SUTTON IAN DICKINSON STEVEN HOGGETT FOR AUTOGRAPH FOR FRANTIC ASSEMBLY ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR RESIDENT DIRECTOR ELLE WHILE KIM PEARCE COMPANY VOICE WORK DIALECT COACH CASTING CHARMIAN HOARE JEANNETTE NELSON JILL GREEN CDG The Cast Christopher Boone JOSHUA JENKINS SAM NEWTON* Siobhan JULIE HALE Ed DAVID MICHAELS Judy