Detroit Symphony Orchestra SIXTEN EHRLING, Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duo Montagnard

albums, and touring throughout the U.S.A. He works as an instructor at the Musician’s Institute in Hollywood where he teaches composition. He has also held part-time teaching positions at UC Irvine and UC Riverside. www.christiandubeau.com ABOUT DAVID CONTE David Conte is the composer of over one hundred and fifty works published by E. C. Schirmer Music Company, including 7 operas, works for chorus, solo voice, orchestra, band, and chamber music. He has received commissions from Chanticleer, the San Francisco Symphony Chorus, the Oakland, Stockton, and Dayton Symphonies, the Atlantic Classical Orchestra, and from the American Guild of Organists. In 2007 he received the Raymond Brock commission from the American Choral Directors Association, one of the nation’s highest honors in choral music. He co-wrote the film score for the acclaimed documentary Ballets Russes, shown at the Sundance and Toronto Film Festivals in 2005, and composed the music for the PBS documentary, Orozco: Man of Fire, shown on GUEST ARTIST RECITAL the American Masters Series in the fall of 2007. In 1982, Conte lived and worked with Aaron Copland while preparing a study of the composer’s sketches, having received a Fulbright Fellowship for study with Copland’s teacher Nadia Boulanger in Paris, where he was one of her last students. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Bowling Green State University and his master’s and doctoral degrees from Cornell University. He is Professor of Composition and Chair of the Composition Department at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. In 2010 he was appointed to the composition faculty of the European American Musical Alliance in Paris. -

Reflections Recital Program Notes

A Faculty Recital Performance by Christopher Hernacki Reflections Welcome! About the recital This performance is themed around the various working relationships I have had the pleasure of sharing during my time living in Michigan. It features music from close friends, colleagues, and the lineage of teachers from which they studied. The concert is presented as a faculty recital at the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam as well as part of the dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts from the University of Michigan. Enjoy the performance! Program Christopher Hernacki, Trombone Ling Lo, Piano Saturday, March 27th, 2021, 3:00pm SUNY Potsdam, Crane School of Music, Sara M. Snell Music Theater https://www.potsdam.edu/academics/crane-school-music/crane-school-music-live-concert The Old Burying Ground: Book I (2003) Evan Chambers I. And Pass From Hence Away (b. 1963) II. Oh Say Grim Death III. A Bar So Pure IV. Oh Drop On My Grave V. Thy Peaceful Reign infinite morning (2009) Joel Puckett (b. 1977) - Intermission - Comments by Computers (2015, rev. 2021) Gala Flagello I. Mulberry Alexa (b. 1994) II. Half a Million III. Even More Shocking IV. Attractive V. Good, Healthy Fun VI. That Big Van VII. The Windowsill VIII. Miss Lulu Trombone Edition Premiere Reflections on the Mississippi (2013) Michael Daugherty I. Mist (b. 1954) II. Fury III. Prayer IV. Steamboat Program Notes The Old Burying Ground van Chambers was born in Evan Chambers enjoys walking Alexandria, Louisiana and is in cemeteries as they provide an a Professor of Composition ideal place to meditate upon how Eat the University of Michigan. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: COMPOSITIONS for FLUTE BY

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: COMPOSITIONS FOR FLUTE BY AMERICAN STUDENTS OF NADIA BOULANGER Jessica Guinn Dunnavant, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor William Montgomery School of Music Throughout the twen tieth century, young American composers made a pilgrimage across the Atlantic Ocean to study their craft with Nadia Boulanger (1887- 1979). Many of them wrote substantial, interesting works for flute, and this dissertation focuses on performances of a selection of those compositions. Boulanger’s life is well documented, as is her reputation for helping her students find their own musical voices. In this project she serves as a lens through which three generations of American composers may be viewed. This to pic brings together a wide variety of flute music in almost every style imaginable. A selection of music to perform was made because the amount of music far exceeds the amount of available performance time. A list of Nadia Boulanger’s American students was primarily derived from the website nadiaboulanger.org and from composers listed in the two editions of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. These lists are far from comprehensive and other notable flute composers have been added. The followin g is an alphabetical list of the works that were performed: Alexander’s Monody, Amlin’s Sonata , Bassett’s Illuminations, Berlinski’s Sonata , Carter’s Scrivo in Vento , Cooper’s Sonata , Copland’s Duo, Dahl’s Variations on a Swedish Folktune, Diamond’s Sonata , Erb’s Music for Mother Bear, Finney’s Two Ballades , Glass’s Serenade, Kraft’s A Single Voice , La Montaine’s Sonata , Lewis’s Monophony I, Mekeel’s The Shape of Silence , Piston’s Sonata , Pasatieri’s Sonata , Rorem’s Mountain Song, and Thomson’s Sonata . -

CORE REPERTOIRE for BAND by Fred J

CORE REPERTOIRE FOR BAND by Fred J. Allen, Director of Bands, Stephen F. Austin State University. This list represents the major works for band by the most important and influential composers for band. Inclusion in this list is based on (1.) the universal acceptance of the composer and (2.) the frequency the specific pieces are recorded and/or mentioned in other repertoire lists and surveys. [updated: August 8, 2001] I. Major Pieces by Major Composers--the “Central Core” (*other significant original wind works available) Warren Benson* 1924- American The Leaves Are Falling The Passing Bell Aaron Copland* 1900-1990 American Emblems Fanfare for the Common Man Outdoor Overture Variations on a Shaker Melody Ingolf Dahl* 1912-1958 German, of Swedish parentage Sinfonietta Percy Aldridge Grainger* 1882-1961 Australian/American Children’s March Colonial Song Country Gardens Duke of Marlboro Fanfare Hill Song No. 2 Irish Tune from the County Derry The Lads of Wamphray Lincolnshire Posy Molly on the Shore Shepherd’s Hey Ye Banks and Braes O’ Bonnie Doon Paul Hindemith* 1895-1963 German Geschwindmarsch from Symphonia Serena Konzertmusik, Op. 41 Symphony in B-flat Gustav Holst* 1874-1934 British First Suite in E-flat,Op. 28, No. 1 Hammersmith, Prelude and Scherzo, Op. 52 Second Suite in F, Op. 28, No. 2 Karel Husa* 1921- Czech Al Fresco Music for Prague 1968 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791* Viennese Serenade No. 10 in B-flat, K. 361 “Gran Partita” Serenade No. 11 in Eb, K.375 Serenade No. 12 in c minor, K. 388 Arnold Schoenberg 1874-1951 Viennese, Am. -

Cbarber Repertoire

Carolyn A. Barber University of Nebraska-Lincoln Conducting Repertoire, 2001-present UNL Wind Ensemble 2016 April 15th, Kimball Recital Hall Roger Zare, Tangents (2014) *Nebraska premiere performance Frank Felice, Power Plays (2013) *Nebraska premiere performance, UNL commission Carter Pann, The Three Embraces (2013) Scott McAllister, Black Dog (2002) Hannah Bell, clarinet Michael Torke, Bliss (2013 edition) Jonathan Newman, Blow It Up, Start Again (2012) February 25th, CBDNA North Central Division Conference February 28th, Kimball Recital Hall Dana Wilson, Piece of Mind (1987) Gernot Wolfgang, Three Short Stories (2012) Kimberly Archer, Common Threads (2016) **World premiere performance, UNL commission Morton Gould, Ballad for Band (1947) Donald Grantham, Fantasy Variations (1998) 2015 December 7th, Kimball Recital Hall Ryan George, Firefly (2008) Melanie Settle, graduate associate conductor Huck Hodge, The Language of Shadows (2011) *Nebraska premiere performance, UNL commission Paul Dukas / Cailliet, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897) Adam Silversmith, Alien Robots Unite (2014) *Nebraska premiere performance W. Francis McBeth, Of Sailors and Whales (1990) Malcolm Arnold / Woodfield, The Padstow Lifeboat (1967) October 7th, Kimball Recital Hall Karel Husa, Cheetah (2007) Kathryn Salfelder, Shadows Ablaze (2015) *Nebraska premiere performance Morton Lauridsen / Reynolds, Contre Qui, Rose (1993) Wayne Oquin, Affirmation (2014) *Nebraska premiere performance David Maslanka, Unending Stream of Life (2007) Ron Nelson, Medieval Suite: Homage to Perotin (1982) April 22nd, Kimball Recital Hall Gernot Wolfgang, Three Short Stories (2012) *Nebraska premiere performance James Syler, Congo Square (2014) *World premiere performance (national consortium) Michael Colgrass, Urban Requiem (1995) Frank Ticheli, Blue Shades (1997) March 18th, Kimball Recital Hall David Del Tredici, In Wartime (2003) Robert Kurka, Good Soldier Schweik Suite (1957) James Dreiling, doctoral associate conductor Michael Daugherty, Brooklyn Bridge, mvt. -

Music for Solo Bassoon and Bassoon Quartet by Pulitzer Prize Winners: A

MUSIC FOR SOLO BASSOON AND BASSOON QUARTET BY PULITZER PRIZE WINNERS: A GUIDE TO PERFORMANCE Jason Walter Worzbyt, B.S., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2002 APPROVED Kathleen Reynolds, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor James Gillespie, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Worzbyt, Jason Walter, Music for Solo Bassoon and Bassoon Quartet by Pulitzer Prize Winners: A Guide to Performance. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2002, 52 pp., 28 examples, bibliography, 18 titles. The Pulitzer Prize in Music has been associated with excellence in American composition since 1943, when it first honored William Schuman for his Secular Cantata No. 2: A Free Song. In the years that followed, this award has recognized America’s most eminent composers, placing many of their works in the standard orchestral, chamber and solo repertoire. Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, Walter Piston and Elliott Carter are but a few of the composers who have been honored by this most prestigious award. Several of these Pulitzer Prize-winning composers have made significant contributions to the solo and chamber music repertories of the bassoon, an instrument that had a limited repertoire until the beginning of the twentieth century. The purpose of this project is to draw attention to the fact that America’s most honored composers have enlarged and enriched the repertoire of the solo bassoon and bassoon quartet. The works that will be discussed in this document include: Quartettino for Four Bassoons (1939) – William Schuman, Three Inventions for Solo Bassoon (1962) – George Perle, Canzonetta (1962) – John Harbison, Metamorphoses for Bassoon Solo (1991) – Leslie Bassett and “How like pellucid statues, Daddy. -

Bassett Family Newsletter, Volume XIV, Issue 2, 21 Feb 2016 (1

Bassett Family Newsletter, Volume XIV, Issue 2, 21 Feb 2016 (1) Welcome (2) Bassett Corn Watch Fob for Bassett Grain Co. of Indiana (3) Leslie Raymond Bassett. Pulitzer Prize Winner of Music (4) Death of Isaac Newton Bassett, Aledo, Illinois lawyer (5) Margaret (Bassett) Nicholas of the Passamaquoddy Tribe of Maine (6) Emile Braun Bassett and the Bassett & Vollum Company (7) Death of Trevor Norman Bassett of New Zealand (8) New family lines combined or added since the last newsletter (9) DNA project update Section 1 - Welcome This month marks the end of a nearly two year travel assignment for work. I hope to have more time in the next few months to catch up with Bassett research and correspondence. Correction to the December 2007 newsletter New research has shown an error in a previous newsletter. George Thomas Bassett descends from the #184B Bassetts of Chiddingstone as follows: John Bassett of Chiddingstone, England Henry Bassett died 1585 Thomas Bassett (b. 1566) and wife Kateryne Michael Bassett (b. 1611) and wife Ann Killick John Bassett (b. 1646) and wife Ann Cronke John Bassett (b. 1695) and wife Elizabeth Saxby Michael Bassett (b. 1741) and wife Mary Killick John Bassett (b. 1761) and wife Mary Wallis Henry Bassett (b. 1808) in Edenbridge and wife Eliza George Thomas Bassett (b. 1841) in Lingfield, Surrey * * * * * Section 2 - Featured Bassett: Corn Watch Fob for Bassett Grain Co. Edward Wilson Bassett descends from William Bassett of Plymouth as follows: William Bassett and wife Elizabeth William Bassett (b. 1624) and wife Mary Raynesford William Bassett (b. 1656) and wife Rachel Williston William Bassett (b. -

Spring Festival

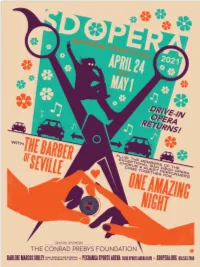

2020-2021 SEASON SPRING FESTIVAL Dear Friends: Estimados amigos: Welcome to this performance of Bienvenidos a esta función del Festival de Auto-Ópera San Diego Opera’s Spring Drive-in de Primavera de San Diego Opera. Festival. Basándonos en el éxito de la producción de la Auto- Building on the successes of our Ópera La Bohème, una vez más hemos encontrado October drive-in production of una solución innovadora, que les permita reunirse de La Bohème, we’ve once again forma segura con otros amantes de la ópera en una DAVID BENNETT found an innovative solution presentación en vivo. General Director that allows you to safely gather San Diego Opera with other opera lovers for live En este festival, les traemos cuatro funciones llenas de performances. diversión de la muy apreciada y vibrante comedia El Barbero de Sevilla de Rossini y Una Noche Extraordinaria: In this festival, we bring together four fun-filled Cuando te vuelva a ver, con la participación de los performances of Rossini’s beloved sparkling comedy The magníficos miembros del Coro de San Diego Ópera y Barber of Seville and One Amazing Night: When I See talentosos artistas invitados de la región. Your Face Again, featuring the wonderful members of the San Diego Opera Chorus and talented local guest artists. En cada función, los invitamos a que visiten nuestros camiones de comida o a disfrutar su propia comida y At each performance, we invite you to visit our food bebida, reclinen sus asientos hacia atrás y pónganse trucks or enjoy your own food and drink, move your seats cómodos, suban el volumen de su radio de FM y gocen back and get comfortable, turn up the volume on your lo que tanto hemos estado extrañando – puestas en FM radio, and enjoy what we all have been missing so escena de ópera en vivo. -

Shepherd School Symphony Orchestra

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LARRY RACHLEFF, music director MAIKO SASAKI, clarinet Friday, February 17, 2006 8:00 p.m. Stude Concert Hall 1975-2005 Ce l e b rating ~I/} Years THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL ~ SlC RlCE UNIVERSITY PROGRAM The Infernal Machine Christopher Rouse (b. 1949) Clarinet Concerto, Op. 57 Carl Nielsen / Allegretto un poco - Paco adagio - (1865-1931) Allegro non troppo -Allegro vivace Maiko Sasaki, soloist David West, snare drum Daniel Myssyk, conductor / INTERMISSION Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88 Antonin Dvorak Allegro con brio (1841-1904) Adagio Allegretto grazioso Allegro, ma non troppo The reverberative acoustics of Stude Concert Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) English Horn Tuba \. Cecilia Weinkaujf, Nicholas Mauro Lillian Copeland Jason Doherty concertmaster Anna Van Devender Aubrey Foard ANNE AND CHARLES DUNCA CHAIR Clarinet f Jessica Blackwell Cello Sergei Vassiliev Harp Steven Zander Peng Li, principal Melanie Yamada Emilia Perfetti Jessica Tong Christine Kim Sadie Turner Rebecca Corruccini Stephanie Hunt E-flat Clarinet Kristiana Matthes Jennifer Humphreys Brian Viliunas Keyboard Sonya Harasim Mira Costa Levi Hammer Kaoru Suzuki Jay Tilton Bass Clarinet CHARLOTTE A. ROTHWELL CHAIR Pei-Ju Wu Madeleine Kabat Philip Broderick Timpani David Mansouri Marie-Michel Beauparlant Craig Hauschildt ' Martin Dimitrov Sarah Wilson -

An Annotated Bibliography of Works by Pulitzer Prizewinning Composers for Solo Viola, Viola with Keyboard, and Viola with Orchestra Michael Alan Weaver

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Bibliography of Works by Pulitzer Prizewinning Composers for Solo Viola, Viola with Keyboard, and Viola with Orchestra Michael Alan Weaver Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS BY PULITZER PRIZEWINNING COMPOSERS FOR SOLO VIOLA, VIOLA WITH KEYBOARD, AND VIOLA WITH ORCHESTRA by MICHAEL ALAN WEAVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 Copyright © 2003 Michael Alan Weaver All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Michael Alan Weaver defended on April 1, 2003. Pamela Ryan Professor Directing Treatise Michael Allen Outside Committee Member Phillip Spurgeon Committee Member Karen Clarke Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Cathy. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In a project this size, there are always several people and organizations to thank. First, I would like to thank my Doctoral Committee for their gracious encouragement, patience, and guidance, and for the valuable time and effort they freely gave: Pamela Ryan, Karen Clarke, Phillip Spurgeon and Michael Allen. I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to Christopher Rouse, Becky Starobin (on behalf -

AMERICAN SYMPHONIES Composers

AMERICAN SYMPHONIES A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers P-Z JOHN KNOWLES PAINE (1839-1906) Born in Portland, Maine. He studied organ, piano, harmony and counterpoint with Hermann Krotzschmar as well as organ with Carl August Haupt and orchestration and composition with Wilhelm Wieprecht in Berlin, Germany. He then toured in Europe for three years. After returning to the U.S. and settling in Boston, he became a member of the faculty of Harvard where he remained for over 4 decades teaching composition to a whole generation of American composers. His catalogue includes operas, incidental music, orchestral, chamber and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 23 (1875) JoAnn Falletta/ulster Orchestra ( + The Tempest and As You Like It Overture) NAXOS 8.559747 (2013) Karl Krueger/American Arts Orchestra SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE AMERICAN MUSICAL HERITAGE MIA-103 (LP) (1959) Zubin Mehta/New York Philharmonic ( + As You Like It Overture) NEW WORLD RECORDS NW 374-2 (1989) Symphony No. 2 in A major, Op. 34 "In Spring" (1879) JoAnn Faletta/Ulster Orchestra ( + Oedipus Tyrannus: Prelude and Poseidon and Amphitrite) NAXOS 8.559748 (2015) Karl Krueger/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE AMERICAN MUSICAL HERITAGE MIA-120 (LP) (1965) Zubin Mehta/New York Philharmonic NEW WORLD RECORDS NW 350-2 (1987) THOMAS PASATIERI (b. 1945) Born in New York City. He began composing at age 10 and, as a teenager, studied with Nadia Boulanger., before entering the Juilliard School at age 16. He has taught composition at the Juilliard School, the Manhattan School of Music, and the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music. -

17T ANNUAL PACIFIC NORTHWEST MUSIC FESTIVAL

University of Washington 2004-2005 School ofMusic COM -c Presents the blSc t3 y Z-~5 17t ANNUAL 2-g PACIFIC NORTHWEST MUSIC FESTIVAL FESTIVAL C OORDINATOR M ITCHELL LUTCH GUEST CLINICIANS FRANK BATTISTI DAVID FuLLMER GARWOOD WHALEY JUNIOR HIGH/MIDDLE SCHOOL CONCERT BANDS Monday, February 7, 2005 'v ~ HIGH SCHOOL CONCERT BANDS Tuesday, February 8, 2005 UNIVERSITY OF W ASIDNGTON WIND ENSEMBLE Timothy Salzman, conductor OJ . ! VI BOGORODlTSE DEVO (J 915) ...................'2.2-0 ~ .................................. SERGEI RACHMANINOFF (1873-1943) MOTOWN METAL (1994) ...............~.: . ~.................................... MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) I . CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET (1950) ........j .................................. A LEXANDER ARUTUNlAN (b. 1920) Brian Chinn, trompet, UW student soloist DOWN A RiVER OF T TME, . -:;-. 1\ A CONCERTO FOR OBOE AND CHA MBER WINDS (2001) ............................... ERIC EWAZEN 111. ... and memories o/tomorrow (b. 1954) Jennifer Muehrcke, oboe, UW student oloist ? ~,) REDLINE TANGO (.004) ....................................................................... .. .JOHN MAcKEY (b. 1973) ( Lj SECOND SUITE IN F FOR MiLITARY B AND (1922) .......... :::........................ G USTAV IIOLST I. March (1874-1934) ll. Song Witholll Words Ill. Song 0/ the Blacksmith IV. Fantasia on 'The Dargason I Frank Battisti, guest onduclor 2005 Pacific Northwest Music Festival Monday. Febnlary 7, 2005 JUNIOR HIGH/MIDDLE SCHOOL CONCERT BAND DIVL lON School Warm-up Performancel Clinic ECKSTEIN MS,lntenn diate Band 7:30