Engaging Older Vols for Web 11.11.02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience Corps-Who Are the Members-AARP

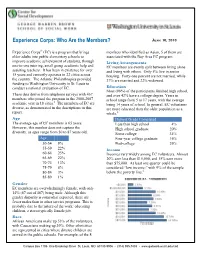

Experience Corps: Who Are the Members? June 10, 2010 Experience Corps® (EC) is a program that brings members who identified as Asian, 5 of them are older adults into public elementary schools to associated with the Bay Area EC program. improve academic achievement of students, through Living Arrangements one-to-one tutoring, small group academic help and EC members are evenly split between living alone assisting teachers. It has been in existence for over and living with others. Only 5% live in senior 15 years and currently operates in 22 cities across housing. Forty-one percent are not married, while the country. The Atlantic Philanthropies provided 37% are married and 22% widowed. funding to Washington University in St. Louis to conduct a national evaluation of EC. Education Most (96%) of the participants finished high school, These data derive from telephone surveys with 467 and over 42% have a college degree. Years in members who joined the program in the 2006-2007 1 school range from 5 to 17 years, with the average academic year in 18 cities. The members of EC are being 14 years of school. In general, EC volunteers diverse, as demonstrated in the descriptions in this are more educated than the older population as a report. whole.2 Age Highest Grade Completed The average age of EC members is 65 years. Less than high school 4% However, this number does not capture the High school graduate 20% diversity, as ages range from 50 to 87 years old. Some college 34% Age Four-year college graduate 16% 50-54 8% Post-college 26% 55-59 22% Income 60-64 23% Incomes vary widely among EC volunteers. -

Locations National Sponsors AARP Experience Corps Has Proven

Highlights (2012-13) An award-winning national program, AARP Experience Corps® engages people 27,112 students tutored 50 and older in addressing one of their communities’ greatest challenges, reading 1,737 tutors literacy. In the 2012-13 school year, 1,737 AARP Experience Corps tutors, serving 173 schools in 20 cities across the nation, provided academic tutoring and mentoring to 27,112 512,990 service hours kindergarten through third-grade students struggling to learn to read. Locations AARP Experience Corps Has Proven Results Baltimore, MD AARP Experience Corps is an evidence-based intervention with significant results Beaumont, TX from multiple independent studies. Berkley, CA A rigorous study from Washington University and Mathematica Policy Institute Boston, MA which included more than 800 first-, second- and third-grade students at 23 urban Chicago, IL schools in three cities found statistically significant reading gains for Experience Cleveland, OH Corps students.1 Evansville, IN • Students who work with AARP Experience Corps tutors for a single school year Grand Rapids, MI experience more than 60 percent greater gains in critical literacy skills when Greater New Haven, CT compared to similar students who were not served by Experience Corps. Marin County, CA • Teachers overwhelming rate the program as beneficial to their students and no or Minneapolis, MN low burden to them. New York City, NY A study from Johns Hopkins University of 1,194 children in kindergarten through Oakland, CA third grade from six urban elementary schools, found not only positive reading Philadelphia, PA outcomes for students but also positive behavioral outcomes.2 Port Arthur, TX Portland, OR • Third grade children whose schools were randomly selected for the program had Revere, MA significantly higher scores on a standardized reading test than children in the San Francisco, CA control schools. -

This Project Has Provided Additional Documentation in A

HIGH STAKES BIG IMPACT Experience Corps works with students who have the greatest need, teaching one of the hardest and most critical skills to learn and producing measurable, meaningful results. Experience Corps tutors improve young students’ reading comprehension, one of the toughest skills to affect for struggling readers. Students who work with Experience Corps tutors for a single school year experience more than 60 percent greater gains in two critical literacy skills—sounding out new words and reading comprehension—compared to similar students who were not served This research shows that by Experience Corps. “ Experience Corps tutors can increase student reading Results include findings from a new, independent, rigorous study of more than 800 skills. That’s great news for first, second, and third grade students at 23 urban schools in three cities. parents, children, educators, The two-year, $2 million study was conducted by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and Mathematica Policy Research, and funded by The Atlantic Philanthropies. and the many people of all It builds on research from Johns Hopkins University that looked at how Experience Corps ages who want to respond affects children, schools, and the tutors themselves. to President Obama’s call to service and want to know As an intervention, Experience Corps compares to smaller class size. that their efforts will make Students with Experience Corps tutors get a boost in reading skills equivalent to the boost a significant difference. they would get from being assigned to a classroom with 40 percent fewer children. JEAN GROSSMAN ” Students gain significantly in reading achievement. -

Experience Corps in Urban Elementary Schools-A Survey Of

POLICY STUDIES ASSOCIATES, INC. 18 CONNECTICUT AVENUE, N.W. • SUITE 400 • WASHINGTON, D.C. 20009 (202) 939-9780 • (202) 939-5732 FAX • WWW.POLICYSTUDIES.COM Experience Corps in Urban Elementary Schools: A Survey of Principals Brenda J. Turnbull Dwayne L. Smith January 2004 SUMMARY Principals, coping with the press of ever-rising academic expectations and constant administrative challenges, have no time for programs that do not serve their purposes. Experience Corps – which places teams of older adults as tutors and mentors in urban elementary schools – has won their allegiance and respect. A survey of principals in whose schools the program operated in 2002-2003 shows that: • Principals believe it has contributed to their students’ academic performance. • Principals cite the personal relationships between Experience Corps members and students, and between members and teachers, as contributing to a positive school atmosphere. • In comparison with other programs, principals cite not only Experience Corps’ advantage of intergenerational benefits, but also the advantages of the reliability of members and the coordination provided by the local office. BACKGROUND: THE EXPERIENCE CORPS PROGRAM AND THIS SURVEY Experience Corps aims to boost children’s academic performance and to yield a wide array of other benefits for children, teachers, classrooms, and the school as a whole. Since 1995, when services began in a handful of schools on a pilot basis, Experience Corps has placed teams of older adults in an ever- growing number of schools. In 2002-03, the Experience Corps program operated in 12 cities. With further expansion planned, the Experience Corps leadership wanted to know how the program’s services are viewed in participating schools. -

ED459304.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 304 UD 034 612 AUTHOR Hartmann, Tracey; Watson, Bernardine H.; Kantorek, Brian TITLE Community Change for Youth Development in Kansas City: A Case Study of How a Traditional Youth-Serving Organization (YMCA) Becomes a Community Builder. INSTITUTION Public/Private Ventures, Philadelphia, PA. SPONS AGENCY Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City, MO.; Ford Foundation, New York, NY.; Annie E. Casey Foundation, Baltimore, MD.; Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC.; Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY.; Mott (C.S.) Foundation, Flint, MI.; Charles Hayden Foundation, New York, NY.; Surdna Foundation, Inc., New York, NY.; Pinkerton Foundation, New York, NY.; Booth Ferris Foundation, New York, NY. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 27p.; Also funded by the Altman Foundation, the Clark Foundation, and the Merck Family Fund. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.ppv.org/pdffiles/kc.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Development; Adolescents; Community Involvement; *Community Programs; Program Development; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Missouri (Kansas City); *Young Mens Christian Association ABSTRACT Kansas City, Missouri, is one of six sites in a national demonstration project, Community Change for Youth Development (CCYD), which aims to increase basic developmental supports and opportunities available to youth age 12-20 years. The demonstration focuses on five basic elements: adult support and guidance, opportunities for involvement in decision making, support through critical transitions, opportunities for using work as a developmental tool, and provision of positive activities after school, in the evenings, on weekends, and during the summer. The lead agency is the YMCA of Greater Kansas City, a traditional youth-serving organization. -

National Service in Massachusetts

National Service in Massachusetts MEETING COMMUNITY NEEDS IN MASSACHUSETTS Senior Corps: More than 7,000 seniors in Massachusetts More than 11,000 people of all ages and backgrounds are helping to contribute their time and talents in one of three Senior Corps meet local needs, strengthen communities, and increase civic programs. Foster Grandparents serve one-on-one as tutors and engagement through national service in Massachusetts. Serving at mentors to more than 7,200 young people who have special more than 1,400 locations throughout the state, these citizens tutor needs. Senior Companions help more than 610 homebound and mentor children, support veterans and military families, provide seniors and other adults maintain independence in their own health services, restore the environment, respond to disasters, homes. RSVP volunteers conduct safety patrols, renovate homes, increase economic opportunity, and recruit and manage volunteers. protect the environment, tutor and mentor youth, respond to natural disasters, and provide other services through more than This year, the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) 590 groups across Massachusetts. will commit more than $39,970,000 to support Massachusetts communities through national service initiatives. CNCS invests in cost-effective community solutions--working hand in hand with local partners to improve lives, expand economic opportunity, and engage citizens in solving problems in their communities. Serving in many of the state's most impoverished communities, CNCS provides vital support to schools, food banks, homeless shelters, community health Social Innovation Fund: The Social Innovation Fund transforms clinics, youth centers, veterans service facilities, and other nonprofit lives and communities using limited federal investment as a and faith-based organizations at a time of growing demand for catalyst to grow the impact of nonprofits with evidence of strong services. -

The Cradle Through College Pipeline: Supporting Children's Development Through Evidence-Based Practices

The Cradle through College Pipeline: Supporting Children's Development through Evidence-Based Practices A Document from the Harlem Children’s Zone TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 5 HARLEM CHILDREN’S ZONE PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS 9 PROMISING PRACTICE PROGRAMS AND EVALUATED COMMUNITIES 14 COMMUNITY PROGRAMS 17 HCZ Programs: Community Pride, Family Support Center 17 Similar Promising Practice Program: 17 Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP) 17 FAMILY, SOCIAL SERVICE, AND HEALTH PROGRAMS 18 HCZ Programs: Baby College, Three Year Old Journey, Harlem Children’s Zone Asthma Initiative, Harlem Children’s Zone Healthy Living Initiative 18 Similar Promising Practice Programs: 18 Playing & Learning Strategies (PALS I & II) 18 Early Head Start 18 Healthy Families New York 19 Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP) 19 Nurse-Family Partnership 20 Triple P (Positive Parenting Program) 20 Project CARE 21 Experience Corps 21 Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) 21 Early Adolescent Anger Reduction Intervention 22 Adolescent Transitions Program (ATP) 22 EARLY CHILDHOOD PROGRAMS 23 HCZ Programs: Get Ready for Pre-K, Harlem Gems, Harlem Gems Head Start 23 Similar Promising Practice Programs: 23 Carolina Abecedarian Project 23 High/Scope Perry Preschool 23 The Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) 24 The Incredible Years 24 Project CARE 24 Sound Foundations 24 Al’s Pals: Kids Making Healthy Choices 25 Chicago Child Parent Centers 25 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PROGRAMS 26 HCZ Programs: Promise Academy Charter School, Peacemakers 26 2 Similar Promising Practice -

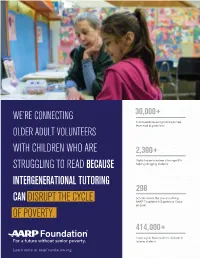

Experience Corps Fact Sheet 2018 No Crop

WE’RE CONNECTING 30,000+ K-3 students receiving tutoring to help OLDER ADULT VOLUNTEERS them read at grade level WITH CHILDREN WHO ARE 2,300+ Highly trained volunteer tutors age 50+ STRUGGLING TO READ BECAUSE helping struggling students INTERGENERATIONAL TUTORING 298 CAN DISRUPT THE CYCLE Schools across the country utilizing AARP Foundation’s Experience Corps OF POVERTY. program 414,000+ Hours a year that volunteers dedicate to tutoring students Learn more at aarpfoundation.org WHY THIS ISSUE CAN’T WAIT Statistics show that children who are not able to read at grade level by fourth grade are four times more likely not to graduate from high school, and this can contribute to a cycle of poverty. OUR TRANSFORMATIVE SOLUTION Results from multiple independent evaluations prove that Experience Corps leads to significant reading gains for students who have struggled with reading. Our volunteers connect to their community and rediscover purpose in their lives while children become great readers and escape the cycle of poverty. TRAINING AND SUPPORT COMPOUNDING THE BENEFITS TRAINING AND SUPPORT COMPOUNDING THE BENEFITS Volunteers receive extensive training and Experience Corps not only helps children staff support to enable them to successfully become great readers but also helps meet the children's needs. volunteers become more fulfilled and lifts up schools and communities. BRING EXPERIENCE CORPS COMPOUNDINGVOLUNTEER THE WITH BENEFITS TO YOUR COMMUNITY EXPERIENCE CORPS We’re working in close partnership with Experience Corps has many ways to help you get municipalities, community agencies, and school involved as a tutor and mentor. With volunteer districts across the country to expand the program.