1 This Is a Manuscript Version in English of a Chapter That Will Appear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Better This World Fact Sheet FINAL

POV Communications: 212-989-7425. Emergency contact: 646-729-4748 Cynthia Lopez, [email protected] POV online pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom “Better This World” Tells Gripping Tale of Idealism, Activism, Crime And Betrayal, Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2011, on PBS’ POV Series; Film Streams on POV Website Sept. 7 – Oct. 8 How Did Two Boyhood Friends from Midland, Texas Find Themselves Accused Of Domestic Terrorism? A Co-production of ITVS in Association with American Documentary / POV “Structured like a taut thriller . delivers a chilling depiction of loyalty, naïveté, political zealotry and the post-9/11 security state.” — Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post MEDIA ALERT – FACT SHEET Premiere: Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega’s Better This World has its national broadcast premiere on Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2011 at 10 p.m. on PBS as part of the 24th season of POV (Point of View). The film will stream on the POV website, www.pbs.org/pov/betterthisworld, from Sept. 7 to Oct. 8. Now in its 24th year, POV is American television’s longest-running independent documentary series and is the winner of a Special Emmy Award for Excellence in Television Documentary Filmmaking, the International Documentary Association’s Award for Best Continuing Series and NALIP’s 2011 Award for Corporate Commitment to Diversity. The film: The story of Bradley Crowder and David McKay, who were accused of intending to firebomb the 2008 Republican National Convention, is a dramatic tale of idealism, loyalty, crime and betrayal. Better This World follows the radicalization of these boyhood friends from Midland, Texas, under the tutelage of revolutionary activist Brandon Darby. -

Radicalization”

Policing “Radicalization” Amna Akbar* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 810 I. Radicalization Briefly Historicized ........................................................................... 818 II. Radicalization Defined and Deconstructed ........................................................... 833 III. Policing the New Terrorism ................................................................................... 845 A. Standards ........................................................................................................ 846 B. Tactics ............................................................................................................. 854 1. Mapping .................................................................................................. 855 2. Voluntary Interviews ............................................................................ 859 3. Informants .............................................................................................. 861 4. Internet Monitoring .............................................................................. 865 5. Community Engagement ..................................................................... 866 IV. Radical Harms ........................................................................................................... 868 A. Religion, Politics, and Geography .............................................................. 869 B. A Fundamental Tension -

The Public Eye, Summer 2009

The Right's Magic Beyond Tea Parties, p.3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH PublicEye ASSOCIATES SUMMER 2009 • Volume XXIV, No.2 $5.25 Remembering the New Right Political Strategy and the Building of the GOP Coalition By Richard J. Meagher hen the Washington Post ran an Wobituary for Paul Weyrich on its front page last December, the casual reader could be forgiven for not recognizing the name. But those who followed conserva- tive politics inside Washington probably approved of the significant placement. Weyrich was the creator or co-creator of a dozen prominent conservative institutions over the past 35 years, and hosted weekly meetings over that span where conservative activists and government officials shared ideas and strategies with each other. While no single person is responsible for the strik- ing success of conservative policies and politics since the 1970s, Weyrich probably comes closest to deserving that credit. Weyrich was at the center of what in the Reagan era was called the “New Right.” This moniker, typically contrasted with the “Old Right” of Robert Taft and Barry David Paul Morris/Getty Images In February, California mosques discovered the FBI had hired a con man to infiltrate their communities. Goldwater, is often misunderstood. Many journalists and scholars have misused the From Movements to Mosques, Remembering the New Right continues on page 5 Informants Endanger Democracy IN THIS ISSUE By Thomas Cincotta Letter to the Editor ...................2 n February,2009, members of the Islamic Monteilh for a while. -

Moving Testimonies and the Geography of Suffering: Perils and Fantasies of Belonging After Katrina

Continuum Journal of Media & Cultural Studies ISSN: 1030-4312 (Print) 1469-3666 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccon20 Moving testimonies and the geography of suffering: Perils and fantasies of belonging after Katrina Janet Walker To cite this article: Janet Walker (2010) Moving testimonies and the geography of suffering: Perils and fantasies of belonging after Katrina, Continuum, 24:1, 47-64, DOI: 10.1080/10304310903380769 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310903380769 Published online: 28 Jan 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 307 Citing articles: 6 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccon20 Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies Vol. 24, No. 1, February 2010, 47–64 Moving testimonies and the geography of suffering: Perils and fantasies of belonging after Katrina Janet Walker* Department of Film and Media Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA This essay explores the use of situated testimony in documentary films and videos about belonging, displacement, and return while calling for a ‘spatial turn’ in trauma studies. Through an analysis of selected works about Hurricane Katrina (Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke, Tia Lessin and Carl Deal’s Trouble the Water, and the activist video New Orleans for Sale! by Brandan Odums, Nik Richard, and the group 2-cent), this paper extrapolates from Cathy Caruth’s insights about psychoanalytic ‘belatedness’ and critical human geography’s anti-essentializing conceptions of place to expose the concomitant materiality and unassimilability of traumatic space. -

Anarchism, Violence, and Brandon Darby's Politics of Moral Certitude

Anarchist library Anti-Copyright Anarchism, Violence, and Brandon Darby’s Politics of Moral Certitude M. J. Essex M. J. Essex Anarchism, Violence, and Brandon Darby’s Politics of Moral Certitude 2009 Retrieved on August 2, 2009 from friendlyfirecollective.info Incomplete editing in original version, please double check for readability / coherence. older version here: neworleans.indymedia.org en.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 Contents New Antiauthoritarian Possibilities? ............ 6 The Crescent City Connection ............... 9 Common Ground Had Much Deeper Problems, Like Its Brandon Darbys .................... 15 Embracing the State ..................... 17 Moral Clarity and Violence? . 19 3 why. Instead, it offers a political philosophy of freedom and re- I was in Austin, Texas of all places when the story of Brandon sponsibility to act against the organized forms of authoritarian vi- Crowder and David McKay first broke; two young men arrested olence and hierarchical oppression of the state, capital, patriarchy, in St. Paul, charged with planning to use firebombs during the and white supremacy. If it is anything, anarchism is a skepticism protests against the Republican National Convention. They were of concentrated power and authority and a creative exploration of quickly demonized by the media, portrayed as dangerously ideal- increasingly egalitarian and free forms of relating to one another istic young men bent on terroristic violence. Crowder and McKay, through cooperation. It requires humility and agnosticism to ques- now known as the Texas Two, have since been convicted and are tions of what is ultimately right and moral. Instead, it challenges serving sentences of two and four years respectively. us to incessantly search for better means and ends, knowing that It was not long after their arrest when case files started toleak the search, the process itself is joyful and painful. -

We Are All Palestinians!

We Are All Palestinians! Solidarity against Massacres and Occupation! By Michael Novick, Anti-Racist Action-Los Angeles/People Against Racist Terror (ARA-LA/PART) It is one of the odd conceits of US mythology that history is measured in Huwaida Arraf (Cyprus): +357-96-723-999, [email protected], presidential administrations (or occasionally in decade-long “generations”). Angela Godfrey-Goldstein (Jerusalem): +972-547-366-393, [email protected] and The unleashing of the Israeli onslaught on the Palestinians in Gaza during the Ramzi Kysia (U.S): +1-703-994-5422, [email protected]. interregnum between Bush-43 and “Agent of Change” Obama makes it clear that this demarcation serves only the interests of the Empire. The convenient use by Meanwhile the efforts by the Israeli to prevent media coverage of their massacres has the Zionists of the “Who’s watching the store?” period between the election and resulted in the first stirrings of complaint even from the docile US media lapdogs, reflecting perhaps a certain unease or division among US rulers about the costs or inauguration of Obama allows Bush and Obama alike to pretend that their bloody consequences of Zionist intransigence. The Los Angeles Times went so far as to fingerprints are not all over the bombing, invasion and massacre.The Israelis print an op-ed piece directly from Mousa Abu Marzook of Hamas. He declared: have several weeks to create the “facts on the ground” while this pretense of “Palestinians everywhere mark the closing of the Bush era with relief. Nevertheless, U.S. non-involvement continues. skepticism runs high that any justice for our people might come from a new president who remained ominously silent in the presence of the latest Israeli onslaught, and who The Israelis and their Zionist apologists in the US profess to be outraged by comparisons has aligned himself so thoroughly with Israel’s interests, so long in advance of taking of Israel to the nazis and fascists, because, as one opined in the LA Times, there are power. -

Rahim V. FBI, 947 F.Supp.2D 631 (2013)

Rahim v. F.B.I., 947 F.Supp.2d 631 (2013) 947 F.Supp.2d 631 United States District Court, ORDER AND REASONS E.D. Louisiana. Malik RAHIM, Plaintiff SUSIE MORGAN, District Judge. v. Before the Court is a motion for summary judgment filed FEDERAL BUREAU of INVESTIGATION, et al., by Defendants, the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) Defendants. and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) (together, 1 Civil Action No. 11–2850. | May 31, 2013. “Defendants”). Plaintiff, Malik Rahim (“Plaintiff”), opposes the motion.2 For the following reasons, the motion is GRANTED in all respects.3 Synopsis 1 R. Doc. 23. Defendants have also filed a reply Background: Department of Justice (DOJ) and the memorandum. See R. Docs. 30 and 32. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) moved for summary judgment in Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) case filed by founder of Hurricane Katrina relief organization. 2 R. Doc. 26. Holdings: The District Court, Susie Morgan, J., held that: 3 The parties have represented to the Court that there are no disputed material facts that would prevent this [1] requester’s appeal did not satisfy the exhaustion matter from being summarily resolved on the briefs. requirements, and See R. Doc. 33. [2] FBI’s Glomar response properly invoked FOIA exemption protecting records whose disclosure would constitute an unwarranted invasion of individual’s privacy. Background Defendants’ motion granted. Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on August 29, 2005. In the days following the storm, Plaintiff, with others, founded Common Ground Relief (“CGR” or “the Attorneys and Law Firms organization”) in order to provide short-term relief to Gulf Coast storm victims, as well as long-term support for *633 Davida Finger, William Patrick Quigley, Loyola rebuilding communities in the greater New Orleans, Law School Clinic, Miles W. -

Strengthening the Global Refugee Protection System

MARCH 2018 Strengthening the Global Refugee Protection System S1 Introduction S218 Critical Perspectives on Clandestine Migration DONALD KERWIN Facilitation: An Overview of Migrant Smuggling Research S4 New Models of International Agreement for Refugee GABRIELLA SANCHEZ Protection SUSAN MARTIN S237 Kidnapped, Trafficked, Detained? The Implications of Non-state Actor Involvement in Immigration Detention S20 Borders and Duties to the Displaced: Ethical MICHAEL FLYNN Perspectives on the Global Refugee Protection System S258 “They Need to Give Us a Voice”: Lessons from DAVID HOLLENBACH, SJ Listening to Unaccompanied Central American and Mexican Children on Helping Children Like S38 Rethinking the Assumptions of Refugee Policy: Themselves Beyond Individualism to the Challenge of Inclusive SUSAN SCHMIDT Communities GEORGE RUPP S283 Seeking a Rational Approach to a Regional Refugee Crisis: Lessons from the Summer 2014 “Surge” of S45 Responding to a Refugee Influx: Lessons from Lebanon Central American Women and Children at the US- NINETTE KELLEY Mexico Border KAREN MUSALO and EUNICE LEE S68 Prospects for Responsibility Sharing in the Refugee Context S326 Refugee, Asylum, and Related Legislation in the US VOLKER TÜRK Congress 2013-2016 TARA MAGNER S83 Matching Systems for Refugees WILL JONES and ALEX TEYTELBOYM S350 How Robust Refugee Protection Policies Can Strengthen Human and National Security S98 You Are Not Welcome Here Anymore: Restoring DONALD KERWIN Support for Refugee Resettlement in the Age of Trump S408 Another Story: What Public Opinion -

Playful, Irreverent, and Deadly Serious, Black Flags and Windmills Is

“Playful, irreverent, and deadly serious, Black Flags and Windmills is . a moving testimony of love, solidarity, betrayal, and the collective struggle for the freedom that so many of us yearn for.” —David Naguib Pellow, author of Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice “It is a brilliant, detailed, and humble book written with total frankness and at the same time a revolutionary poet’s passion. It makes the reader feel that we too, with our emergency heart as our guide, can do anything; we only need to begin.” —Marina Sitrin, author of Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina “This is a compelling tale for our times.” —Bill Ayers, author of Fugitive Days “This book is a key document in that real and a remarkable story of an activ- ist’s personal and philosophical evolution.” —Rebecca Solnit, author of A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster “ . crow is a puppetmaster involved in direct action” —FBI (Joint Terrorism Task Force internal memo) “Black Flags and Windmills introduced me to countless contemporary free- thinkers and rule-breakers whose very lives are emblematic of what it means to be liberated.” —Diana Welch, coauthor of The Kids Are All Right “A frenetic account of how grassroots power, block-to-block outreach, and radically visionary approaches to sustainability can rattle the ruling class and transform people is positively searing.” —Ernesto Aguilar, cofounder of People of Color Organize “This book is an example that should be studied by activists -

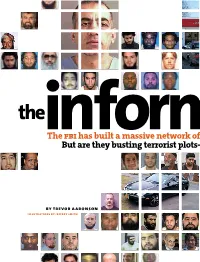

The Fbi Has Built a Massive Network of Spies to Prevent Another Domestic Attack

the The fbi has built a massive network of spies to prevent another domestic attack. infor But are they busting terroristmants plots—or leading them? by trevor aaronson illustrations by jeffrey smith The fbi has built a massive network of spies to prevent another domestic attack. infor But are they busting terroristmants plots—or leading them? photos from government sources and trevor aaronson except ap photos (8), n ewscom/afp/getty (2), and r euters (1). ames Cromitie was a man of bluster and bigotry. He made up wild stories The bureau’s answer has been a strategy about his supposed exploits, like the one about firing gas bombs into police known variously as “preemption,” “pre- precincts using a flare gun, and he ranted about Jews. “The worst brother in vention,” and “disruption”—identifying and neutralizing potential lone wolves the whole Islamic world is better than 10 billion Yahudi,” he once said. before they move toward action. To that A 45-year-old Walmart stocker who’d adopted the name Abdul Rahman after end, FBI agents and informants target not converting to Islam during a prison stint for selling cocaine, Cromitie had lots just active jihadists, but tens of thousands of worries—convincing his wife he wasn’t sleeping around, keeping up with the of law-abiding people, seeking to identify those disgruntled few who might partici- rent, finding a decent job despite his felony record. But he dreamed of making pate in a plot given the means and the op- his mark. He confided as much in a middle-aged Pakistani he knew as Maqsood. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 11, 2014 No. 90 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was direct result of the administration’s in- 4805, the No Subsidies Without Verifi- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- sistence on moving forward with their cation Act of 2014. pore (Mr. SMITH of Missouri). arbitrary October 1, 2013, open enroll- The tax credits and cost-sharing as- f ment date, regardless of the con- sistance for ObamaCare premiums ad- sequences. ministered by HHS is estimated to DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Consider the problem this presents as amount to a staggering $10 billion per TEMPORE there is currently no realtime system month, making this one of the largest The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- in place to ensure only those who qual- entitlement programs in the Nation. fore the House the following commu- ify for subsidies receive them. This My bill would simply require an in- nication from the Speaker: means that hardworking American tax- come verification system to be put into WASHINGTON, DC, payers may be left on the hook for po- place before any additional taxpayer June 11, 2014. tentially billions of dollars in fraudu- subsidies are given out. I hereby appoint the Honorable JASON T. lent subsidy payments. Furthermore, it Mr. Speaker, ObamaCare has become SMITH to act as Speaker pro tempore on this means that someone who simply fills such a boondoggle that the nonpartisan day. -

Anarchism, Violence, and Brandon Darby's Politics of Moral Certitude

Anarchism, Violence, and Brandon Darby’s Politics of Moral Certitude M. J. Essex 2009 Contents New Antiauthoritarian Possibilities? .................... 4 The Crescent City Connection ....................... 6 Common Ground Had Much Deeper Problems, Like Its Brandon Darbys 10 Embracing the State ............................. 12 Moral Clarity and Violence? ........................ 13 2 I was in Austin, Texas of all places when the story of Brandon Crowder and David McKay first broke; two young men arrested in St. Paul, charged with plan- ning to use firebombs during the protests against the Republican National Conven- tion. They were quickly demonized by the media, portrayed as dangerously ideal- istic young men bent on terroristic violence. Crowder and McKay, now known as the Texas Two, have since been convicted and are serving sentences of two and four years respectively. It was not long after their arrest when case files started to leak out. By thistime I was back in New Orleans, a place I’ve been living and working, on and off since Katrina, since I came down here like thousands of others to work in solidarity with the displaced and dispossessed. From the big humid city One day I remember read- ing a press report in the big humid city identifying one “Brandon Darby” as an FBI informant who would provide key evidence and testimony against Crowder and McKay. Speculation was quick and intense: was this the same Darby from Austin, Texas who had worked in New Orleans after Katrina at Common Ground? Darby himself soon fessed up to the facts and revealed his status as an FBI informant in a now infamous open letter published on Indymedia (publish.indymedia.org).