A Study of North American Charcuterie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Different Methods of Preservation on the Quality of Cattle and Goat Meat

Bang. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 38(1&2) : 86 – 91 ISSN 0003-3588 EFFECT OF DIFFERENT METHODS OF PRESERVATION ON THE QUALITY OF CATTLE AND GOAT MEAT S. Bin. Faisal, S. Akhter1 and M. M. Hossain Abstract The study was conducted to evaluate the effect of drying, curing and freezing on the quality of cattle and goat meat collected and designed as. Cattle and goat meat samples were: dried cattle meat with salt (M1), dried cattle meat without salt (M2), dried goat meat with salt (M3), dried goat meat without salt (M4), cured cattle meat with salt (M5), cured cattle meat with sugar (M6), cured goat meat with salt (M7), cured goat meat with sugar (M8), frozen cattle meat with salt (M9), frozen cattle meat without salt (M10), frozen goat meat with salt (M11) and frozen goat meat without salt (M12) and analyze on every 30 days interval up to the period of 120 days. Chemical constituents of meat samples (dry matter, protein, ash and fat) decreased gradually with the increasing of storage time, but dry matter increased gradually during freezing period. The initial dry matter, ash, protein and fat contents of the samples (M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M6, M7, M8, M9, M10, M11, M12) ranged from 81.26 to 98.50%, 15.01 to 22.46%, 60.28 to 77.30% and 3.04 to 6.70% and final value were ranged from 80.03 to 88.12%, 10.92 to 18.50%, 57.98 to 68.93% and 2.50 to 5.90%, respectively. The elapse of storage time quality parameters of meat samples degraded significantly (P<0.05 to 0.01). -

Charcuterie Cheese

Charcuterie Cheese 1 for $9 • 2 for $17 • 3 for $25 1 for $7 • 2 for $12 • 3 for $17 4 for $32 • 5 for $37 4 for $21 • 5 for $25 {Portion size may vary} {1.5 ounce portions} FRESH WHOLE CUTS BLUE Alligator Tasso spicy/sweet/smoky Saint Agur Bleu France/cow/triple cream Duck Ham cured & smoked Gorgonzola Dolcé Italy/cow/mild/creamy Billy Bleu Wisconsin/goat/tangy Great Hill Blue* Massachusetts/cow/crumbly/feta-like SAUSAGES & TERRINES HARD Duck Terrine dried cherries/fennel/red pepper Derby & Port Wine England/cow/cheddar with port Wild Boar Terrine sweet spices/pepper/dates English Tickler Cheddar England/cow/nutty/crystalline Fresh Poblano Sausage pork/spicy/smoky Paradiso Reserve Gouda Holland/cow/“fudgy” Mortadella mild pork/lardons Cave-Aged Gruyere* French/cow/nutty/smooth Istara P’tit Basque French/sheep/nutty/sweet/creamy WHIPS & JAMS SEMI-FIRM Duck Liver Mousse truffle-scented Honey Bee Goat Gouda Wisconsin /goat/sweet/tangy Bacon Spuma buttery/bacony/whipped Mahon Semicured Bonvallis* Spain/cow/bold/smooth/paprika Bourbon Bacon Jam sweet & savory Tartufo Perlagrigia Italy/cow/truffles/vegetable ash/creamy Shiitake Paté vegetarian/earthy/rich & creamy Campo de Montalban Spain/cow,sheep&goat/fruity/Manchego Rosemary Manchego* Spain/sheep/tangy/herbal CURED MEAT – WHOLE CUTS SEMI-SOFT Bresaola wagyu beef/coffee/cardamom Mobay Wisconsin /sheep&goat/grape vine ash Pancetta pork belly/salt cured Port Salut France/cow/mild/creamy Coppa pork neck/black pepper/fennel Taleggio D.O.P. Italy/cow/funky/earthy/washed rind Duck Prosciutto duck -

Shelf-Stable Food Safety

United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Food Safety Information PhotoDisc Shelf-Stable Food Safety ver since man was a hunter-gatherer, he has sought ways to preserve food safely. People living in cold climates Elearned to freeze food for future use, and after electricity was invented, freezers and refrigerators kept food safe. But except for drying, packing in sugar syrup, or salting, keeping perishable food safe without refrigeration is a truly modern invention. What does “shelf stable” Foods that can be safely stored at room temperature, or “on the shelf,” mean? are called “shelf stable.” These non-perishable products include jerky, country hams, canned and bottled foods, rice, pasta, flour, sugar, spices, oils, and foods processed in aseptic or retort packages and other products that do not require refrigeration until after opening. Not all canned goods are shelf stable. Some canned food, such as some canned ham and seafood, are not safe at room temperature. These will be labeled “Keep Refrigerated.” How are foods made In order to be shelf stable, perishable food must be treated by heat and/ shelf stable? or dried to destroy foodborne microorganisms that can cause illness or spoil food. Food can be packaged in sterile, airtight containers. All foods eventually spoil if not preserved. CANNED FOODS What is the history of Napoleon is considered “the father” of canning. He offered 12,000 French canning? francs to anyone who could find a way to prevent military food supplies from spoiling. Napoleon himself presented the prize in 1795 to chef Nicholas Appert, who invented the process of packing meat and poultry in glass bottles, corking them, and submerging them in boiling water. -

Product List May 2019 Poultry, Meat & Fish

PRODUCT LIST MAY 2019 POULTRY, MEAT & FISH Leathams started by selling meats and today we have a superb range of poultry, meat and fish products specifically for the professional chef. We have fish for all occasions and lots of great raw, cooked, cured and smoked meat and poultry. TOO= To Order Only 2 POULTRY, MEAT & FISH MIN WEIGHT/PACK CASE CODE DESCRIPTION UNIT OF SALE TEMP TOO? SHELF NEW? FORMAT SIZE LIFE BEEF BEE002 Cajun Beef Brisket 1Kg 10 EACH FROZEN 250 BEE200 Chefs Brigade® Roast Beef Thinly Sliced (16-25) 500g 6 TRAY CHILLED 11 BEE201 Pre-Sliced Rare Roast Beef 400g 20 PACK FROZEN 540 BEE400 Salt Beef, Sliced (31-45) 1Kg 4 TRAY CHILLED 16 CHARCUTERIE - ITALIAN Mixed Antipasto (Coppa, Salami Milano & Finocchiona approx. 10 CHA002 slices) 265g 10 PACK CHILLED 85 CHA004 Coppa 250g 12 TRAY CHILLED 60 CHA008 Mixed Antipasti (Prosc, Coppa, Fennel) 65g 15 EACH CHILLED 50 CHA009 N'Duja 500g 10 TRAY CHILLED 40 CHA031 Salami Milano 500g 8 EACH CHILLED YES 60 CHA113 Calabrese Antipasti Copa, Panc & Schi 200g 5 PACK CHILLED 55 CHA117 Salsiccia Piccante 1Kg 6 EACH CHILLED YES 60 CHA202 Charcuti® Mortadella, Sliced (approx. 25 slices) 250g 8 TRAY CHILLED 40 CHA203 Charcuti® Salsiccia Piccante, Sliced (approx. 53 slices) 250g 8 TRAY CHILLED 50 Charcuti® Mixed Antipasti (Prosciutto, Spianata, Milano approx. 12 CHA204 slices) 135g 8 TRAY CHILLED 50 CHA205 Charcuti® Bresaola, Sliced (approx. 7 slices) 70g 8 TRAY CHILLED 50 Antipasti (Salami Milano, Salami Napoli, Prosciutto Crudo, Coppa / CHA213 ave.8 Prosciutto, 12 coppa, 12s. Milano, 12 s. -

Cured and Air Dried 1

Cured and Air Dried 1. Sobrasada Bellota Ibérico 2. Jamón Serrano 18 month 3. Mini Cooking Chorizo 4. Morcilla 5. Chorizo Ibérico Bellota Cure and simple Good meat, salt, smoke, time. The fundamentals of great curing are not complicated, so it’s extraordinary just how many different styles, flavours and textures can be found around the world. We’ve spent 20 years tracking down the very best in a cured meat odyssey that has seen us wander beneath holm oak trees in the Spanish dehesa, climb mountains in Italy and get hopelessly lost in the Scottish Highlands. The meaty treasures we’ve brought back range from hams and sausages to salamis and coppas, each with their own story to tell and unique flavours that are specific to a particular place. 1. An ancient art 4. The practice of preserving meat by drying, salting or smoking stretches back thousands of years and while the process has evolved, there has been a renaissance in traditional skills and techniques in recent years. Many of our artisan producers work in much the same way as their forefathers would have, creating truly authentic, exquisite flavours. If you would like to order from our range or want to know more about a product, please contact your Harvey & Brockless account manager or speak to our customer support team. 3. 2. 5. Smoked Air Dried Pork Loin Sliced 90g CA248 British Suffolk Salami, Brundish, Suffolk The latest edition to the Suffolk Salami range, cured and There’s been a cured meat revolution in the UK in recent years smoked on the farm it is a delicate finely textured meat that with a new generation of artisan producers developing air dried should be savoured as the focus of an antipasti board. -

The Evaluation of Pathogen Survival in Dry Cured Charcuterie Style Sausages

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Animal and Food Sciences Animal and Food Sciences 2019 THE EVALUATION OF PATHOGEN SURVIVAL IN DRY CURED CHARCUTERIE STYLE SAUSAGES Jennifer Michelle McNeil University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.074 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McNeil, Jennifer Michelle, "THE EVALUATION OF PATHOGEN SURVIVAL IN DRY CURED CHARCUTERIE STYLE SAUSAGES" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Animal and Food Sciences. 102. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/animalsci_etds/102 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal and Food Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Animal and Food Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Soups + Salads Charcuterie + Cheese Starters Raw +

• • ESTABLISHED “HE HAS SEEN 2020 THEM ALL.” • • STARTERS *Maryland Style Crab Cake 22 Black Hawk Farm Meatballs 16 Jumbo Lump Crab, Cajun Remoulade, Herb Salad Country Ham Pomodoro, Mozzarella, Focaccia Toast Deviled Eggs 15 Kung Pao Calamari 14 Paddlefish Caviar, Crème Fraiche, Rye Cracker Sorghum Chile Crisp, Peanut, Celery, Lime CHARCUTERIE + CHEESE TABLESIDE • SLICED TO ORDER Pony Board 25 Thoroughbred Board 44 Selection of 3 Meats & 3 Cheeses Selection of 6 Meats & 6 Cheeses An assortment of Peach Jam, Sorghum Mustard, House Made Pickles, Marcona Almonds, Honeycomb, and Pretzel Toast Points will be available with the Charcuterie + Cheese selections RAW + CHILLED TABLESIDE • FRESH SELECTIONS DAILY *East or West Coast Oyster 3.5 Maine Lobster Tail 14 *Chef’s Selection of Tartare I Ceviche I Crudo 14 Pacific Tiger Shrimp 3.5 Alaskan King Crab 36 ∞ Winner’s Circle Grand Plateau 130 ∞ Chef’s Selection Of Items From The Raw + Chilled Bar A selection of Old Bay Mignonette, Bloody Mary Cocktail, Horseradish + Lemon will be available with Raw Bar selections SOUPS + SALADS French Onion Soup 14 Matt Winn’s Wedge Salad 15 Copper & Kings Brandy, Kenny’s Kentucky Rose, Smoked Blue Cheese Dressing, Candied Broadbent Bacon, Duck Fat Crouton Preserved Tomato, Pickled Onion, Sieved Egg Lobster Bisque 14 Kentucky Bibb Lettuce 15 Butter Poached Lobster, Scallion Oil Mt. Tam Brie, Roasted Butternut Squash, Toasted Pumpkin Seeds, Spice Apple Cider Vinaigrette, Brioche Crouton Classic Caesar Salad 15 Romaine Lettuce, White Anchovies, Parmigiano-Reggiano, Garlic Wafer ∞ ADD PROTEIN ∞ *Verlasso Salmon 18 *Petite Filet of Beef 38 Heritage Chicken Breast 14 Grilled Tiger Prawns 16 *Please be advised that consuming undercooked or raw fish, shellfish, eggs, or meat may increase your risk of foodborne illness. -

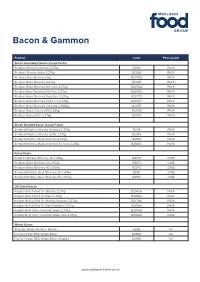

Bacon & Gammon

Bacon & Gammon Product Code Pricing Unit Sliced Unsmoked Bacon (Large Packs) Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B203 PACK Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B203S PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2kg B207D2 PACK Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B207D PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B207DA PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Rib Free 2.27kg B207DR PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Supertrim 2.27kg B207ST PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Thick Cut 2.27kg B207DT PACK Rindless Back Stirchley Catering 2.268kg B207E PACK Rindless Back Classic (A11) 2.25kg B207M PACK Rindless Back Selfar 2.27kg B207S PACK Sliced Smoked Bacon (Large Packs) Smoked Rindless Streaky Stirchley 2.27kg B204 PACK Smoked Rindless Streaky Selfar 2.27kg B204S PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 2.27kg B218D PACK Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley Dry Cure 2.27kg B218DC PACK Retail Packs Rindless Streaky Stirchley 20 x 454g B2031 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2071 CASE Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B207C CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 20 x 454g B2181 CASE Smoked Rindless Back Stirchley 40 x 200g B218C CASE UK Sliced Bacon Knights British Rind On Streaky 2.27kg B206UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back 2.27kg B208UK PACK Knights British Rind On Streaky Smoked 2.27kg B217UK PACK Knights British Rind On Back Smoked 2.27kg B219UK PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back 2.27kg B207UD PACK Knights British Dry Cured R/L Back Smk 2.27kg B218UD PACK Whole Bacon Stirchley Whole Rindless Streaks B258 KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs B255D KG Danish Crown BSD Whole Backs Smoked B259D -

First Thoughts the Cheeses Charcuterie Plate Housemade Pate, Surreyano

first thoughts the cheeses Charcuterie Plate Housemade Pate, Surreyano Ham, Toscano Salami, Caper Berries, Whole Grain Served with Baguette & Walnut Bread Mustard 10 Merguez Corn Dog Spanish Style Lamb Sausage, Cornmeal Batter, Gourmet Popcorn, Mustard Sauce Cheese is served in approxiamately 1 oz. portions. 7 Grilled Flat Bread Mini "Rustic Pizza", one cheese 4 Chef's Selection of Daily Ingredients 8 Stuffed Peppadew Peppers Small Sweet/Spicy Peppers, three cheese 12 Filled with Herb & Olive Ricotta Cheese 8 Tomato & Caramelized Onion Soup 6 five cheese 19 Veggies & Dip Seasonal Raw Vegetables, Ginger & Tomato Dip 4 Braised Pork Foreshank Slathered with a Barbecue Sauce, Rainbow Ridge "Meridian" Goat / NY Red Cabbage Slaw 11 Firefly Farms "Mountain Top Blue" Goat / MD greens Tumalo Farms "Tumalo Classico" Goat / OR Mesclun Fresh Herbs, Roasted Shallots, Seasonal Hudson Valley Camembert Sheep / NY Grilled Vegetables, Lemon Vinaigrette 7 Baby Arugula & Watercress Shaved Serrano Ham, Sally Jackson Sheep Raw Sheep / WA Crme Fraiche, Balsamic Vinaigrette 8 Shrimp Salad Baby Red Oak, Clementine Major Farms "Vermont Shepherd" Sheep / VT Vinaigrette 10 Warm Frisee Lardons, Poached Egg, White Wine Shepherd's Way "Big Woods Blue" Sheep / MN Vin 9 Grilled Caesar Romaine Hearts, White Anchovies 8 Cowgirl Creamery "Mt. Tam" Cow / CA Add Chicken 13 Add Shrimp 15 Meadow Creek Dairy "White Top" Cow / VA thoughts on bread Chaples "Cave Aged" Raw Cow / MD hot Uplands Cheese "Pleasant Ridge Reserve" Cow / WI Grilled Gruyere & Ham Dijon Mustard, on White 8 Hooks "Gorgonzola" Cow / WI Grilled Humboldt Fog & Pear on White 7 Carr Valley "Gran Canaria" Goat / Sheep / Cow / WI Grilled Pleasant Ridge W. -

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (From Either the French Chair Cuite = Cooked Meat, Or the French Cuiseur De

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (from either the French chair cuite = cooked meat, or the French cuiseur de chair = cook of meat) is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as sausage primarily from pork. The practice goes back to ancient times and can involve the chemical preservation of meats; it is also a means of using up various meat scraps. Hams, for instance, whether smoked, air-cured, salted, or treated by chemical means, are examples of charcuterie. The French word for a person who prepares charcuterie is charcutier , and that is generally translated into English as "pork butcher." This has led to the mistaken belief that charcuterie can only involve pork. The word refers to the products, particularly (but not limited to) pork specialties such as pâtés, roulades, galantines, crépinettes, etc., which are made and sold in a delicatessen-style shop, also called a charcuterie." SAUSAGE A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted (Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means) meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ A sausage is a food usually made from ground meat , often pork , beef or veal , along with salt, spices and other flavouring and preserving agents filed into a casing traditionally made from intestine , but sometimes synthetic. Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing , drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking or freezing. -

Dent's Canadian History Readers

tS CANADIAHiHISTORY'READEI^S [|Hi 1£Ik« '*•• m a - 111.. 4* r'i f r-jilff '•Hi^wnrii A 1 Hi4-r*^- cbc eBw« BIBXBMIIISB THE CANADIAN^ WEST D. J. DICKIE TORONTO M. DENT (Sf SONS LTD. J. ISdwcatioa f— c. OiT^ PUBLISHERS^ NOTE It has come to the notice of the author and the publishers that certain statements contained in this book are considered by the Hudson's Bay Company to be inaccurate, misleading and unfair to the Company. The author and publishers much regret that any such view is taken and entirely disclaim any intention of defaming the Hudson's Bay Com- pany or of misrepresenting facts. Any future edition of this book will be amended with the assistance of information kindly placed at the disposal of the publishers by the Hudson's Bay Company, LIST OF COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS The First Sale of Furs .... Frontispiece Building the First Fort . facing page 14 Sir Alexander Mackenzie 51 The Trapper • 62 ...... tj The Pack Train t) 129 The Selkirk Sei ti ers take Possession • t > 144 Threshing on the Prairies • >: In the Athabasca Valley • ti 172 . Chief Eagle Tail of the Sarcees . i , 227 Royal North-West Mounted Policeman . „ 238 Cowboy on Bucking Broncho . „ 259 The Coquahalla Valley 270 The! Dani ’Kwi^ Asto The The -Sev® The The \ Gove) 7 I. ,SiPaul The map of Western Canada has been specially drawn for this book by M. J. Hilton. 10 THE CANADIAN WEST GENTLEMEN ADVENTURERS The Charter which Prince Rupert and his friends obtained that memorable night from the easy-going Charles became the corner-stone of the Hudson^s Bay Company^ now the