Unstable Deformation and the Formation of the Equatorial Bulge of Iapetus J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coriolis Effect in Meteorology

THE CORIOLIS EFFECT IN METEOROLOGY On this page I discuss the rotation-of-Earth-effect that is taken into account in Meteorology, where it is referred to as 'the Coriolis effect'. (For the rotation of Earth effect that applies in ballistics, see the following two Java simulations: Great circles and Ballistics). The rotating Earth A key consequence of the Earth's rotation is the deviation from perfectly spherical form: there is an equatorial bulge. The bulge is small; on Earth pictures taken from outer space you can't see it. It may seem unimportant but it's not: what matters for meteorology is an effect that arises from the Earth's rotation and Earth's oblateness together. A model: parabolic dish Thinking about motion over the Earth's surface is rather complicated, so I turn now to a model that is simpler but still presents the feature that gives rise to the Coriolis effect. Source: PAOC, MIT Courtesy of John Marshall The dish in the picture is used by students of Geophysical Fluid Dynamics for lab exercises. This dish was manufactured as follows: a flat platform with a rim was rotating at a very constant angular velocity (10 revolutions per minute), and a synthetic resin was poured onto the platform. The resin flowed out, covering the entire area. It had enough time to reach an equilibrium state before it started to set. The surface was sanded to a very smooth finish. Also, note the construction that is hanging over the dish. The vertical rod is not attached to the table but to the dish; when the dish rotates the rod rotates with it. -

True Polar Wander: Linking Deep and Shallow Geodynamics to Hydro- and Bio-Spheric Hypotheses T

True Polar Wander: linking Deep and Shallow Geodynamics to Hydro- and Bio-Spheric Hypotheses T. D. Raub, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA J. L. Kirschvink, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA D. A. D. Evans, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA © 2007 Elsevier SV. All rights reserved. 5.14.1 Planetary Moment of Inertia and the Spin-Axis 565 5.14.2 Apparent Polar Wander (APW) = Plate motion +TPW 566 5.14.2.1 Different Information in Different Reference Frames 566 5.14.2.2 Type 0' TPW: Mass Redistribution at Clock to Millenial Timescales, of Inconsistent Sense 567 5.14.2.3 Type I TPW: Slow/Prolonged TPW 567 5.14.2.4 Type II TPW: Fast/Multiple/Oscillatory TPW: A Distinct Flavor of Inertial Interchange 569 5.14.2.5 Hypothesized Rapid or Prolonged TPW: Late Paleozoic-Mesozoic 569 5.14.2.6 Hypothesized Rapid or Prolonged TPW: 'Cryogenian'-Ediacaran-Cambrian-Early Paleozoic 571 5.14.2.7 Hypothesized Rapid or Prolonged TPW: Archean to Mesoproterozoic 572 5.14.3 Geodynamic and Geologic Effects and Inferences 572 5.14.3.1 Precision of TPW Magnitude and Rate Estimation 572 5.14.3.2 Physical Oceanographic Effects: Sea Level and Circulation 574 5.14.3.3 Chemical Oceanographic Effects: Carbon Oxidation and Burial 576 5..14.4 Critical Testing of Cryogenian-Cambrian TPW 579 5.14A1 Ediacaran-Cambrian TPW: 'Spinner Diagrams' in the TPW Reference Frame 579 5.14.4.2 Proof of Concept: Independent Reconstruction of Gondwanaland Using Spinner Diagrams 581 5.14.5 Summary: Major Unresolved Issues and Future Work 585 References 586 5.14.1 Planetary Moment of Inertia location ofEarth's daily rotation axis and/or by fluc and the Spin-Axis tuations in the spin rate ('length of day' anomalies). -

Appendix a Glossary

BASICS OF RADIO ASTRONOMY Appendix A Glossary Absolute magnitude Apparent magnitude a star would have at a distance of 10 parsecs (32.6 LY). Absorption lines Dark lines superimposed on a continuous electromagnetic spectrum due to absorption of certain frequencies by the medium through which the radiation has passed. AM Amplitude modulation. Imposing a signal on transmitted energy by varying the intensity of the wave. Amplitude The maximum variation in strength of an electromagnetic wave in one wavelength. Ångstrom Unit of length equal to 10-10 m. Sometimes used to measure wavelengths of visible light. Now largely superseded by the nanometer (10-9 m). Aphelion The point in a body’s orbit (Earth’s, for example) around the sun where the orbiting body is farthest from the sun. Apogee The point in a body’s orbit (the moon’s, for example) around Earth where the orbiting body is farthest from Earth. Apparent magnitude Measure of the observed brightness received from a source. Astrometry Technique of precisely measuring any wobble in a star’s position that might be caused by planets orbiting the star and thus exerting a slight gravitational tug on it. Astronomical horizon The hypothetical interface between Earth and sky, as would be seen by the observer if the surrounding terrain were perfectly flat. Astronomical unit Mean Earth-to-sun distance, approximately 150,000,000 km. Atmospheric window Property of Earth’s atmosphere that allows only certain wave- lengths of electromagnetic energy to pass through, absorbing all other wavelengths. AU Abbreviation for astronomical unit. Azimuth In the horizon coordinate system, the horizontal angle from some arbitrary reference direction (north, usually) clockwise to the object circle. -

This Restless Globe

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 45 - Winter 1999 © 1999, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. This Restless Globe A Look at the Motions of the Earth in Space and How They Are Changing by Donald V. Etz The Major Motions of the Earth How These Motions Are Changing The Orientation of the Earth in Space The Earth's Orbit Precession in Human History The Motions of the Earth and the Climate Conclusion Our restless globe and its companion. While heading out for The Greek philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, said 2500 years ago that the its rendezvous with Jupiter, a camera on NASA's Galileo perceptible world is always changing. spacecraft snapped this 1992 image of Earth and its Moon. The Heraclitus was not mainstream, of course. Among his contemporaries were terminator, or line between night and day, is clearly visible on the philosophers like Zeno of Elea, who used his famous paradoxes to argue that two worlds. Image courtesy of change and motion are logically impossible. And Aristotle, much admired in NASA. ancient Greece and Rome, and the ultimate authority in medieval Europe, declared "...the earth does not move..." We today know that Heraclitus was right, Aristotle was wrong, and Zeno...was a philosopher. Everything in the heavens moves, from the Earth on which we ride to the stars in the most distant galaxies. As James B. Kaler has pointed out in The Ever-Changing Sky: "The astronomer quickly learns that nothing is truly stationary. There are no fixed reference frames..." The Earth's motions in space establish our basic units of time measurement and the yearly cycle of the seasons. -

6. the Gravity Field

6. The Gravity Field Ge 163 4/11/14- Outline • Spherical Harmonics • Gravitational potential in spherical harmonics • Potential in terms of moments of inertia • The Geopotential • Flattening and the excess bulge of the earth • The geoid and geoid height • Non-hydrostatic geoid • Geoid over slabs • Geoid correlation with hot-spots & Ancient Plate boundaries • GRACE: Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment Spherical harmonics ultimately stem from the solution of Laplace’s equation. Find a solution of Laplace’s equation in a spherical coordinate system. ∇2 f = 0 The Laplacian operator can be written as 2 1 ∂ ⎛ 2 ∂f ⎞ 1 ∂ ⎛ ∂f ⎞ 1 ∂ f 2 ⎜ r ⎟ + 2 ⎜ sinθ ⎟ + 2 2 2 = 0 r ∂r ⎝ ∂r ⎠ r sinθ ∂θ ⎝ ∂θ ⎠ r sin θ ∂λ r is radius θ is colatitude λ Is longitude One way to solve the Laplacian in spherical coordinates is through separation of variables f = R(r)P(θ)L(λ) To demonstrate the form of the spherical harmonic, one can take a simple form of R(r ). This is not the only one which solves the equation, but it is sufficient to demonstrate the form of the solution. Guess R(r) = rl f = rl P(θ)L(λ) 1 ∂ ⎛ ∂P(θ)⎞ 1 ∂2 L(λ) l(l + 1) + ⎜ sinθ ⎟ + 2 2 = 0 sinθP(θ) ∂θ ⎝ ∂θ ⎠ sin θL(λ) ∂λ This is the only place where λ appears, consequently it must be equal to a constant 1 ∂2 L(λ) = constant = −m2 m is an integer L(λ) ∂λ 2 L(λ) = Am cos mλ + Bm sin mλ This becomes: 1 ∂ ⎛ ∂P(θ)⎞ ⎡ m2 ⎤ ⎜ sinθ ⎟ + ⎢l(l + 1) − 2 ⎥ P(θ) = 0 sinθ ∂θ ⎝ ∂θ ⎠ ⎣ sin θ ⎦ This equation is known as Legendre’s Associated equation The solution of P(θ) are polynomials in cosθ, involving the integers l and m. -

1 GEOPHYSICAL FLUID DYNAMICS-I OC512/AS509 2015 LECTURES 5-6 Week 3: Coriolis Effects: Introduction to Dynamics of Fluids on a Rotating Planet

1 GEOPHYSICAL FLUID DYNAMICS-I OC512/AS509 2015 LECTURES 5-6 Week 3: Coriolis effects: introduction to dynamics of fluids on a rotating planet. Reading for week 3: Gill 7.1-7.6, 7.9-7.10; (Vallis text §§ 2.8, 3.1, 3.2, 3.4-3.7) Conservation-flux equations in fluids F = ma for a fluid F = body forces + surface contact forces (pressure, viscous stress) + inertial forces due to accelerating frame of reference (rotating Earth). rotating planet reference frame and Coriolis’ theorem for the rate of change of a position vector the Earth’s geopotential surfaces which define the ‘horizontal’ and ‘horizon’. Inertial oscillations and steady forced flow with planet rotation; inertial radius pressure and fluid surface profile with a circular vortex, including Coriolis effects Rossby number geostrophic balance and flow ‘stiffness’ of a fluid with strong Coriolis effects: Taylor-Proudman approximation §1. CONSERVATION-FLUX EQUATIONS We begin with general remarks about conservation equations for a fluid. The dynamical equations of GFD are developed in Gill §4 and §7 and Kundu & Cohen §4 (which includes basic thermodynamics) and in Vallis’ text §§ 2.8, 3.1, 3.2, 3.4-3.7. We will not repeat these entirely, but will repeat some important ideas. Going from basic physics of moving particles to fluids requires important mathematical book-keeping. What is simple for 2 particles is more complex for the ‘billions and billions’ of fluid particles making up our fluids. But, a lot of those fluid particles are doing similar or the same things, and we understand things by considering simple cases. -

The Moon and the Origin of Life on Earth

The Moon and the Origin of Life on Earth Jacques Laskar Laluneet l'origine April 1993∗ del'homme If the Moon did not exist, the orientation of the Earth’s Moon and the Sun. A similar precession of a solid body’s axis axisr JACQUES wouldTASKAR not be stable, and would be subject to large of rotation can easily be observed with an ordinary spinning chaotic variations over the ages. The resulting climatic top. One consequence of this phenomenon is that the Earth’s changesSi la Lune n'existait very likelypas, l'orientation would have de I'axe markedly de rotation disturbedde laTerre the de- rotational axis does not always point toward Polaris, but in- velopmentne seraitpas stable, of organizedet subirait delife. largesvariations chaotiques au cours stead describes a large circle in the celestial sphere. This desAges. Les changementsclimatiques engendrds par cesvariations auraientWe are alors all perturbd familiarfortement with lethe ddveloppement change ofde la seasons vie organisde. due to the fact sometimes disturbs the quibblings of astrologers, since inclination of the equator with respect to the plane of the the precession of the equinoxes has so greatly displaced the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. This inclination of 23◦270, zodiacal calendar from the apparent motion of the Sun that ous sommestous familiersdu lationspossibles de l'obliquit6, et qu'elle Une des cons6quencesde ce ph6no- calledrythme “obliquity” dessaisons, dont la suc- byagit astronomers, donc commeun r6gulateur alsoclimati- givesmdne est rise que toI'axethe de rotation polar de la presently, on the date corresponding to the sign of Aries, the cessionr6sulte de I'inclinaison que de la Terre. -

Chapter 11 Satellite Orbits

CHAPTER 11 SATELLITE ORBITS 11.1 Orbital Mechanics Newton's laws of motion provide the basis for the orbital mechanics. Newton's three laws are briefly (a) the law of inertia which states that a body at rest remains at rest and a body in motion remains in motion unless acted upon by a force, (b) force equals the rate of change of momentum for a body, and (c) the law of equal but opposite forces. For a two body system comprising of the earth and a much smaller object such as a satellite, the motion of the body in the central gravitational field can be written → → dv / dt = -GM r / r3 → where v is the velocity of the body in its orbit, G is the universal gravitational constant (6.67 x 10**11 N m**2/kg**2), M is the mass of the earth, and r is position vector from the centre of mass of the system (assumed to be at the centre of the earth). The radial part of this equation has the more explicit form m d2r/dt2 - mrω2 = -GMm/r2 where ω is the angular velocity and m is the satellite mass. The second term on the left side of the equation is often referred to as the centrifugal force The total energy of the body in its orbit is a constant and is given by the sum of the kinetic and potential energies E = 1/2 m [(dr/dt)2 + r2ω2] - mMG/r . The angular momentum is also conserved so that L = mωr2 , which allows us to rewrite the energy E = 1/2 m (dr/dt)2 + L2/(2mr2) - mMG/r . -

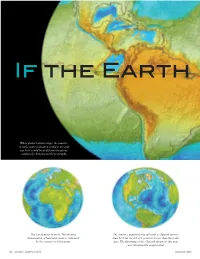

If the Earth Stood Still

If the Earth Stood Still When global rotation stops, the massive oceanic water migration would cease and sea level would be at different locations, completely changing world geography. The world as we know it. The obvious The longer, equatorial axis of Earth’s ellipsoid is more demarcation of land and ocean is indicated than 21.4 km (or 1/3 of 1 percent) longer than the polar by the contour of 0 elevation. axis. The flattening of the ellipsoid shown on this map was intentionally exaggerated. 62 ArcUser Summer 2010 www.esri.com End Notes If the Earth Stood Still Modeling the absence of centrifugal force By Witold Fraczek, ESRI The following is not a futuristic scenario. It is not science fiction. It is a demonstration of the capabilities of GIS to model the results of an extremely unlikely, yet intellectually fascinating query: What would happen if the earth stopped spinning? ArcGIS was used to perform complex raster analysis and volumetric computations and generate maps that visualize these results. The gravity of the still earth is the strongest at the polar regions (shown in green). It is intermediate in the middle latitudes and weakest at the high altitudes of the Continued on page 64 Andes, close to the equator. www.esri.com ArcUser Summer 2010 63 If the Earth Stood Still Continued from page 63 The most significant feature on any map that depicts even a portion of the earth’s ocean is the spatial extent of that water body. Typically, we do not pay much attention to the delineation of the sea because it seems so obvi- ous and constant that we do not realize it is a foundation of geography and the basis for our perception of the physical world. -

Ω the Coriolis Force

Atmospheric Motion Dynamics Newton’s second law F m x dx2 Mass × Acceleration = Force mF= dt2 Thermodynamics Concerned with changes in the internal energy and state of moist air. TMD Lecture 2 Newton’s second law The Coriolis force Newton’s second law A line that rotates with F dx2 the roundabout m mF= dt2 x Ω A line at rest in an inertial system Mass × Acceleration = Force applies in an inertial frame of reference. But we like to make measurements relative to the Earth, which is rotating! Apparent trajectory of the ball in a rotating To do this we must add correction terms in the equation, coordinate system the centrifugal and Coriolis accelerations. The centripetal acceleration/centrifugal force Effective Gravity g is everywhere normal to the earth’s surface 2 outward v 2 =Ω r Ω 2 R 2 force r R R Ω R g* Ω v g g* g r v2 Inward −=−Ω2r acceleration r gg= *+Ω2R effective gravity g on a spherical earth effective gravity on an earth with a slight equatorial bulge When frictional forces can be neglected, F is the pressure Effective Gravity gradient force total pressure F = −∇p T force per unit volume If the earth were a perfect sphere and not rotating, the only gravitational component g* would be radial. ⎛⎞du ρ−Ω∧=+ρ⎜⎟2 uFg dt Because the earth has a bulge and is rotating, the effective ⎝⎠ gravitational force g is the vector sum of the normal gravity to du 1 per the mass distribution g*, together with a centrifugal force =− ∇p T +gu −2Ω ∧ Ω2R, and this has no tangential component at the earth’s dt ρ unit mass surface. -

Your Friend the Coriolis Force

Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Your Friend the Coriolis Force Dale Durran February 9, 2016 1 / 40 Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis I 1792-1843 I Presented results on rotating systems to the Acad´emiedes Sciences in 1831 2 / 40 Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Pop Quiz Does the Coriolis force on an object moving due east vary between Fairbanks and Honolulu? 3 / 40 Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Outline Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain 4 / 40 Setting s to be the position vector drawn from an origin at the center of the Earth, r, Vf = Vr + Ω × r Setting s to be the velocity in the fixed frame Vf D D f V = r V + Ω × V Dt f Dt f f D = r V + 2Ω × V + Ω × (Ω × r) Dt r r Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Rates of Change in a Rotating Frame For any vector s, D D f s = r s + Ω × s Dt Dt 5 / 40 Setting s to be the velocity in the fixed frame Vf D D f V = r V + Ω × V Dt f Dt f f D = r V + 2Ω × V + Ω × (Ω × r) Dt r r Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Rates of Change in a Rotating Frame For any vector s, D D f s = r s + Ω × s Dt Dt Setting s to be the position vector drawn from an origin at the center of the Earth, r, Vf = Vr + Ω × r 5 / 40 Derivation The Merry-Go-Round The Inertial Oscillation Swirl Around a Drain Rates of Change -

Geodetic Measurements Geodesy = Science of the Figure of the Earth

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH - GEODESY, KINEMATICS, DYNAMICS OUTLINE Shape: Geodetic Measurements Geodesy = science of the figure of the Earth; its relation to astronomy and the Earth's gravity field The geoid (mean–sea–level surface) and the reference ellipsoid Large–scale geodetic measurements: crustal deformation and plate movement Kinematics (Motion) Circular motion: angular velocity ! = v=r, centripetal acceleration !2r Rotation = spinning of the Earth on its axis; precession and nutation Revolution = orbital motion of the Earth around the sun Time: solar and sidereal, atomic clocks Dynamics Newton's second law: F = ma Newton's law of gravitation: simplified application to circular orbits; the mass of the Earth and its mean density Moment of inertia and precession: the moment of inertia of the Earth and its density distribution. Background reading: Fowler §2.4 & 5.4, Kearey & Vine §5.6, Lowrie §2.1–2.4 GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE FIGURE OF THE EARTH (1) The reference ellipsoid To a close approximation, the Earth is an ellipsoid. The reference ellipsoid is a best fit to the geoid, which is the surface defined by mean sea level (MSL) and its extension over land. The reference ellipsoid is used to define coordinate systems such as latitude and longitude, universal transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinates, and so on. Strictly speaking, an ellipsoid whose equatorial radius is constant is a spheroid. The parameters of the Hayford international spheroid are: equatorial radius a = 6378:388 km polar radius c = 6356:912 km The ellipticity of the Earth (also called the flattening or oblateness) is a c 1 e = − a ' 297 Its volume is 1:083 1012 km3; the radius of a sphere of equal volume is 6371 km.