A Report on Greek History Education’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M.A. Public History Student Handbook

MASTER OF ARTS CONCENTRATION IN PUBLIC HISTORY GRADUATE STUDENT HANDBOOK ASSEMBLED BY Graduate Director and Director of Public History Department of History Middle Tennessee State University Revised and in effect Fall 2018 DEPARTMENTAL POLICIES AND GUIDELINES DESCRIBED IN THIS HANDBOOK SUPPLEMENT UNIVERSITY POLICIES AND ACADEMIC REGULATIONS, AS ARTICULATED IN THE GRADUATE CATALOG Revised 4/23/19 TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1. CORE COURSES 3 2. SELECTION OF PUBLIC HISTORY SPECIALIZATION 3 3. SELECTION OF MAJOR FIELD AND ADVISOR 4 4. NON-MAJOR FIELD ELECTIVES 4 5. PROFESSIONAL PORTFOLIO REQUIREMENT/GUIDELINES 5 6. PUBLIC HISTORY INTERNSHIP 7 7. THESIS AND NON-THESIS OPTIONS 10 8. SUMMARY OF COURSE REQUIREMENTS 10 9. MAINTAINING SATISFACTORY PROGRESS 11 10. DEGREE PLAN 11 11. COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATIONS: NON-THESIS OPTION 11 12. THESIS 14 13. GRADUATION PROCESS/PAPERWORK 17 14. SUPPORT FOR CONFERENCE TRAVEL & THESIS RESEARCH 17 15. GRADUATE ASSISTANTSHIPS 17 16. SELECTED STUDIES AND ADVANCED PROJECTS COURSES 18 17. DISTANCE LEARNING POLICY 18 FORMS AND GUIDELINES: SUBMIT ALL FORMS TO THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT - GRADUATE PROGRAMS EXECUTIVE AIDE M.A. PUBLIC HISTORY DEGREE PROGRAM CHECKLIST 19 INTERNSHIP AGREEMENT FORMAT FOR HIST 6570 21 INTERNSHIP REPORT REQUIREMENTS FOR HIST 6570 24 REPORT OF M.A. COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION 26 REPORT OF M.A.P.H. PORTFOLIO REVIEW 27 THESIS PROPOSAL ACCEPTANCE FORM 28 M.A. THESIS GUIDELINES 29 SAMPLE THESIS APPROVAL PAGE 32 REQUEST FOR STUDENT TRAVEL ASSISTANCE FORM 33 REQUEST FOR STUDENT TRAVEL REIMBURSEMENT 34 2 1. CORE COURSES: M.A. PUBLIC HISTORY Two courses are required for all students seeking a Master of Arts degree from the History Department: HIST 6010 and HIST 6020. -

(2008-2018): a Case Study on the Greek Public History Magazine “The Illustrated History”1

Representations of the Greek-German relationship in the decade of crisis (2008-2018): a case study on the Greek public history magazine “The Illustrated History”1 Germanos Vasileiadis, University of Western Macedonia Kostis Tsioumis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Ifigeneia Vamvakidou, University of Western Macedonia Ilias Sailakis, University of Western Macedonia Abstract Germany’s tough negotiating tactics during Greek economic crisis, in which harsh austerity measures were imposed in Greek citizens, had produced a bad mood between the relations among the two states and their citizens. This mood is strengthened by the mass media, changing the Greek conception about Germany and E.U. in general. In this research we study on the magazine named as "The History Illustrated" which is the first Greek magazine of public historical material published since 1968 by Papyros editions. Public history as a “nonacademic narrative” plays an important role in the modern construction of national or historic consciousness which create the image of the “other”. The research material is analysed as a multimodal, narrative and visual “text” which describes the past events in many diverse forms of historical narratives. We focus on the choices of the editor using the method of narrative analysis, so as to exact results about what image is formed about Germany and Europe. The research material is structured on (5) references- covers and 15 historical texts that are representing the Greek-German relationship (Issue 506: August 2010, 524: February 2012, 535: January 2013, 540: June 2013, 544: October 2013). Keywords crisis, public history, Greece- Germany 1 If this paper is quoted or referenced, we ask that it be acknowledged as: Vasileaidis, G., Tsioumis, K., Vamvakidou, I., & Sailakis, I. -

Introduction to Public History History 397Z - Fall 2015 - Syllabus

Introduction to Public History History 397Z - Fall 2015 - Syllabus Tu Th 2:30-3:45 in Herter 118 Elizabeth Sharpe Visiting Lecturer Office in Herter 637 Office Hours Thurs 3:45-5:00 or by appt. [email protected] Course Overview The purpose of this course is to introduce the practice of public history and its intellectual foundations. Through class discussions and assignments, we will examine the activities of public historians and the issues they face in their work. Public history encompasses a variety of occupations which all involve, to some degree, collecting, preserving, and interpreting history for the public. Public historians are well-trained historians who may work as museum curators and educators, historic site interpreters, archivists, oral historians, community activists, film and digital media producers, or historic preservationists. They may be employed at nonprofit organizations, cultural institutions, corporations, government agencies, and as independent consultants. The practice of public history typically takes place outside of the traditional academic arena and its audience is the general public—children and adults alike. Yet, the two arenas overlap and public and academic historians often work collaboratively. In addition to looking at the many areas of public history, we will examine related theoretical constructs like heritage, community, commemoration, and memory, and we will explore the many methods of engaging audiences. Class activities and assignments will include practicing some of the basic methods -

Public History Messiah College

HIST 393: Public History Messiah College Fall 2013 instructor: James LaGrand Tuesdays & Thursdays office: Boyer 264 2:45-4:00 p.m. telephone: ext. 7381 Boyer 338 email: [email protected] office hours: Mon., Wed., & Fri., 10:00-11:00 a.m.; Thursdays, 1:20-2:35 p.m., & by apt. DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES: The field of public history has emerged within the history profession over the last several decades and continues to increase in popularity in part because it has helped historians answer two questions that perpetually face them. First--How can historians find fulfilling careers in positions in which they can use their skills and training? And second--How can historians communicate and share developments within the field of history with a wider public beyond that found in college classrooms and at academic conferences? Historians should always be working toward finding answers to these two questions, and many have found the field of public history provides a unique opportunity to do so. Developments in recent years have demonstrated that the public is interested in history and continues to think about it and consume it--but not necessarily as presented by academic historians. Museums, historical theme parks, living re-enactments, television documentaries, and the like have enjoyed great popularity in recent years. Yet too often, historians in colleges and universities have allowed themselves to become ignored and irrelevant, even as history in general enjoys great popularity. Public history has the ability to improve this situation. This course in public history will be run as a seminar--with a primary focus on reading, independent work, presentations of independent work, and discussion. -

Best Practices in Public History for Undergraduate Students

Best Practices in Public History Public History for Undergraduate Students Prepared by the NCPH Curriculum and Training Committee 1, October 2009 Adopted by the NCPH Board of Directors October 2009 Introduction: Nationwide, history departments introduce public history to undergraduate students in a variety of ways. Some departments introduce public history to students as a field, subfield or research method, while other departments offer a major, minor, emphasis, concentration or certificate in public history. Still others offer a class or two on public history theories and/or practices.2 Clearly, the needs and resources of departments are as diverse as their approaches to public history. Below are some recommendations for undergraduate public history “programs” that are flexible.3 These recommendations should provide guidelines but should not be followed as a recipe for a “one-size fits all” approach to introducing undergraduates to public history. Undergraduate training in public history should be designed around the local resources available, the unique interests of department faculty, and the needs of the students. Undergraduate programs that offer public history should keep the following four basic priorities in mind: (1) Provide students with strong training in the basic skills of the historian; (2) Provide students with a solid grounding in historical content; (3) Introduce students early in their studies to the wide variety of careers that incorporate some component of public history; and (4) Encourage students to participate in field-based research, service learning, and/or internships. There are many different reasons why history departments should consider introducing public history at the undergraduate level. The number of undergraduate history majors is on the rise in departments across the country, but students graduating with history degrees and going on to graduate study in history is declining. -

Public History Checksheet: Museums, Historic Preservation, Cultural Resource Management

PUBLIC HISTORY CHECKSHEET: MUSEUMS, HISTORIC PRESERVATION, CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT REQUIRED COURSES FOR ALL CONCENTRATIONS (21 cr.) Required Select one of the following: Select two of the following: HIST 501 Historical Method: Historiography HIST611 Research Seminar: United States HIST520 Reading Seminar: Europe to 1815 HIST511 Reading Seminar: US to 1877 HIST640 Research Seminar: State/Local HIST521 Reading Seminar: Europe since 1815 HIST512 Reading Seminar: US Since 1877 HIST530 Reading Seminar: Africa Select one of the following: HIST531 Reading Seminar: Latin America HIST586 Practicum HIST532 Reading Seminar: Middle East HIST587 Internship HIST533 Reading Seminar: East Asia HIST534 Reading Seminar: South Asia HIST539 Reading Seminar: World Environmental HIST621 Research Seminar: Europe ---------------------------------- PUBLIC HISTORY CONCENTRATIONS (15 cr.) ---------------------------------- MUSEUMS HISTORIC PRESERVATION CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Required: Required: Required: HIST504 Historical Method: Museums HIST503 Historical Methods: Historic Preservation HIST503 Historical Methods: Historic Preservation HIST540 Material Culture HIST354 Am. Architectural History ANTH551 Historic Archaeology OR HIST478 Heritage Resource Management Select one of the following: Select one of the following: Select one of the following: HIST580A1 Historical Methods: Digital History HIST580A1 Historic Methods: Digital History HIST580A1 Historic Methods: Digital History HIST503 Hist. Methods Historic Preservation HIST504 Historic Methods: Museums -

Northeastern University Public History

Northeastern University Public History Northeastern University Department of History 249 Meserve Hall Boston, MA 02215 http://www.northeastern.edu/cssh/history/graduate/programs/ma-with-public-history-concentration/ Director(s): Marty Blatt; Victoria Cain [email protected] 617-373-2662 Program Description: The M.A. in Public History Program has existed since 1974. A combined undergraduate/graduate program, known as Plus One, has existed since 2004 and results in an M.A. in Public History. Students take courses and supervised fieldwork as part of their Public History graduate work. Over 500 students have graduated from the Public History Program and the great majority wishing to do so have found employment in the field. The university is exploring the possibility of offering a certificate in public history to World History Ph.D. graduates and other graduate students. Degrees Offered: • M.A. in History with a Concentration in Public History Program Strengths: Archival practices Public policy Historic Preservation Historical Administration Digital Humanities Material Culture Exhibition Development Museum Studies How Many Students are Admitted Annually: BA: N/A MA:10 PhD: N/A Financial Aid Available: Loans Scholarships Tuition Waiver Deadline to Apply: February 15. Credit Hour Requirement: 30. Internship Requirement: Required. Individual students and faculty work to arrange internships. Places Where Students Have Interned During the Past Three Years: • John F. Kennedy Presidential Library • Metropolitan Waterworks Museum NCPH Online Guide -

Doctor of Philosophy in Public History

Graduate DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Student Handbook IN PUBLIC HISTORY Assembled by Director of Public History Department of History The departmental policies and guidelines described in this handbook supplement university policies and academic regulations, as articulated in the Graduate Catalog 0 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Administration 3 Director of Graduate Programs 3 Director of Public History 3 Graduate Assistant 3 Faculty 3 Committee Chair and Advisory Committee 4 Faculty Fields 5 Curriculum 6 Admission without MA 7 Transfer Credits from MA 7 Registration and Residence Requirements 7 Types of Courses 7 Internship 8 Colloquia in History 9 Research Seminar in Public History 9 Teaching Seminars 9 Dissertation Research Seminars 10 Inter-institutional Courses 10 Dual-level Classes 10 Fields of Study and Reading Lists 10 Public History Field 10 History Field 10 Interdisciplinary Field 10 Dissertation Work 12 Graduate Plan of Work 12 Grades 13 Incomplete Grades 13 Time to Degree 13 Degree Thresholds 13 Language Requirement 14 GIS as a Language 15 Support for Conference Travel and Research 15 Comprehensive Examinations 16 Written Examinations 16 Oral Examinations 17 Dissertation 18 Dissertation Formats 19 The Traditional Dissertation 20 The Article-Style Dissertation 20 The Project-Based Dissertation 21 1 Dissertation Research Courses 22 Thesis and Dissertation Support Services 22 Prospectus and Presentation 22 External Funding and Outside Employment 23 Dissertation Defense 23 Dissertation Filing 24 Graduation 24 Teaching 25 Working with -

What Do Public History Employers Want?

What Do Public History Employers Want? Report of the Joint AASLH-AHA-NCPH-OAH Task Force on Public History Education and Employment Philip Scarpino, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Daniel Vivian, University of Louisville Introduction In the summer and fall of 2015, the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment surveyed public history employers in an effort to understand (1) what skills and knowledge are most valued by employers, and (2) to identify trends in hiring practices. This report summarizes the survey results. It is provided to the four sponsoring organizations while the data is still current. The survey received 401 responses. A survey of alumni of public history M.A. programs is now underway. The results from it will be reported as soon as possible. The public history employer survey shows a field in transition. Employers continue to value fundamental historical skills such as research and writing, historical and historiographical knowledge, oral and written communication, and expertise with public programming and interpretation. These remain central to the work of public historians, irrespective of specialization. At the same time, employers see knowledge of digital media, fundraising, and project management as increasingly important and likely to be in high demand in the future. Respondents also identified several trends that are affecting historical programs and institutions and, in turn, the working conditions of public historians. These include decreasing public funding and support, strong competition for support from philanthropic organizations, and anti-intellectualism. Public historians are being asked to do more with fewer resources and are facing multiple challenges in their efforts to fulfill core responsibilities. -

M a : P U B Lic H Is to Ry

Graduate COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIA L SCIENCES Studies Public History Master of Arts (MA) The Master of Arts Degree in Public History offers options in historic preservation and heritage interpretation. Internship and Employment Opportunities of Recent Graduates/ Graduate Schools The M.A. in Public History: Historic Preservation Option and Programs of Recent Graduates prepares the student for further study or career placement in State Historic Preservation Office, Oklahoma Historic Society museums, historical sites or agencies. Students will develop North Carolina Maritime Museum familiarity with issues in public history, material culture, the historic National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office landscape, and the built environment. Students will participate in Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site field exercises and projects that take history out of the classroom Old Town Cape, Cape Girardeau, MO Main Street program and into public venues. Field Archaeologist at URS Corp Executive Director at Preservation Alliance of Minnesota The M.A. in Public History: Heritage Interpretation Emphasis NEPA Program Manager, Schofield Barracks, Wahiawa, Hawaii prepares the student for fields at the intersection of education and Archaeologist, US Forest Service public history. Students will hone skills aimed at connecting Head, Special Collections and Archives, Idaho State University classrooms with museums and historic sites. Students will develop Curator, Governor’s mansion, Jackson, Mississippi a familiarity with issues confronting social studies teachers and Manuscript Specialist, State Historical Society of Missouri-Kansas City public history educators, study the contexts in which those History Associate, Missouri History Museum professionals work, and develop plans for increasing student Architectural Historian, Historic Preservation Division, Alabama learning in those contexts that highlight the collaborative Historical Commission possibilities between classrooms and public history institutions. -

Northeastern University Public History

Northeastern University Public History Northeastern University Department of History 249 Meserve Hall Boston, MA 02115 USA http://www.neu.edu Director(s): Victoria Cain; Timothy Brown [email protected] 617-373-2662 Program Description: The Master’s level program has existed since 1974; the Public History methodological track in our Global Ph.D. program since 1996. A Public History undergraduate concentration has existed since 1990; a combined undergraduate/graduate Public History concentration since 2004; a non-degree graduate certificate program since 1988. The programs are generalist. Students take courses and supervised fieldwork as part of their History degree and receive a Public History undergraduate concentration or graduate concentration. Approximately 900 students have graduated from these programs and most of those wishing to do so have found employment in the field. Degrees Offered: • B.A. in History with a Concentration in Financial Aid Available: Loans Public History Assistantships • Combined Bachelor’s/Master of Arts Scholarships (“Double with a Certificate or Concentration in Husky” Scholarships for NU grads) Public History Tuition Waiver • M.A. in History with a Certificate or Concentration in Public History Deadline to Apply: Ph.D: January 10; Master’s: • Ph.D. in History with a Certificate or February 1 Concentration in Public History • Non-Degree Graduate Certificate in Credit Hour Requirement: 32 for M.A with 16 in Public History Public History Program Strengths: Internship Requirement: Required. Individual • Archival Practices students and faculty work to arrange • Business internships. • Digital Methodology Places Where Students Have Interned During • Film and Media the Past Three Years: • Historical Administration • Massachusetts Historical Society • Historic Preservation • John F. -

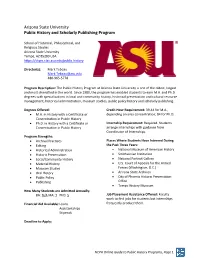

Arizona State University Public History and Scholarly Publishing Program

Arizona State University Public History and Scholarly Publishing Program School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85283 USA https://shprs.clas.asu.edu/public-history Director(s): Mark Tebeau [email protected] 480-965-5778 Program Description: The Public History Program at Arizona State University is one of the oldest, largest and most diversified in the world. Since 1980, the program has enabled students to earn M.A. and Ph.D. degrees with specializations in local and community history, historical preservation and cultural resource management, historical administration, museum studies, public policy history and scholarly publishing. Degrees Offered: Credit Hour Requirement: 39-44 for M.A., • M.A. in History with a Certificate or depending on area concentration; 84 for Ph.D. Concentration in Public History • Ph.D. in History with a Certificate or Internship Requirement: Required. Students Concentration in Public History arrange internships with guidance from Coordinator of Internships. Program Strengths: • Archival Practices Places Where Students Have Interned During • Editing the Past Three Years: • Historical Administration • National Museum of American History • Historic Preservation • Smithsonian Institution • Local/Community History • National Portrait Gallery • Material History • U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed • Museum Studies Forces (Washington, D.C.) • Oral History • Arizona State Archives • Public Policy • City of Phoenix Historic Preservation • Publishing Office • Tempe