Roadmap to Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Longacre's Ledger Vol

Longacre's Ledger Vol. 6, No.1 Winter 1996 l I I I Official Publication Flying Eagle and Indian Cent Collectors Society The "Fly-In Club" Single Copy:$4.50 WINTER 1996 LONGACRE'S LEDGER Oftlcial Publication of the FLYING EAGLE AND INDIAN CENT COLLECTORS SOCIETY FLYING EAGLE AND INDIAN CENT LONGACRE'S LEDGER COLLECTORS SOCIETY Table of Contents WINTER 1996 The purpose of the Flying Eagle and Indian Cent Collectors Society is Lo promote the study and collection of Longacre's design of small cents. President's Letter 4 Announcements................................................................................ 5 OFFICERS Letter's to the Editor. 6 State Representatives 9 President ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Lany R. Steve Back Issues Order Form 36 Vice President ••••••••• c •• • • • • • • • • • •••••••• Chris Pilliod Secretary •••••••••••••• ~ • • • • • • • • • • • • •• Xan Chamberlain Treasurer • • • • • • • • • • • • • • c •• • • • • • • ••••••••• Charles Jones A COUNTERFEIT 1909S INDIAN CENT SURFACES State Representatives by Chris Pilliod 10 Page 9 WHO REALLY SUPPLIES THE NICKEL USED IN THE PRODUCTION OF THE FLYING EAGLE CENTS. ON THE COVER... by Kevin Flynn 13 A POPULATION REPORT RARITY REVIEW: PART II 1857 Flying Eagle Cent SOc Clashed Obverse by W.O. Walker 18 One of three ·different 1857 Flying Eagle cents that show a clash mark Fom a die of another denomination. The outline of a Liberty Seated Half BLOOPERS, BLUNDERS, MPD'S OR NONE OF THE ABOVE DoHar is clearly visible above the eagle's head and wing on the left, and by Marvin Erickson 24 through AMERICA on the right. Note that because of the clashing, it is a mirror image of that which is seen on a nonnal half dollar. HOW MANY ARE THERE ANYWAY? by Jerry Wysong 27 (courtesy Larry Steve, photo by Tom Mull'oney) THE F.IND.ERS ™ REPORT Articles. -

THE HISTORY of the BATSTO Post Office by Arne Englund

Arne Englund ~ HISTORY OF BATSTO PO THE HISTORY of the BATSTO Post Office By Arne Englund The cover shown in Figure 1 is the first reported example of the stampless-era Batsto, NJ CDS. At NOJEX in 2013 I asked one of the cover dealers if he had any New Jersey covers, and he replied that he only had a few, which he’d just acquired. This cover was on the top of the small stack, where it stayed for all of about two seconds(!). Fig. 1. Recently discovered Batsto CDS used in the stampless era, estimated usage between 1853 and 1855, on an envelope addressed to Mr. Sam’l W. Gaskill in Mays Landing. The red BATSTO JAN 10 N.J. CDS measures 30mm. The matching red PAID 3 handstamp measures 22mm. Closeups of each are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Fig. 2: Red CDS not listed in Coles or the Fig. 3: Red Paid marking Coles Update. The cover is not dated, but as the Batsto Post Office was opened June 28, 1852, and as mandatory prepayment of postage by U.S. postage stamps was enacted in March of 1855, the envelope would then date between 1853 and 1855. Vol. 43/No. 4 189 NJPH Whole No. 200 Nov 2015 HISTORY OF BATSTO PO ~ Arne Englund A manuscript BATSTO cancel on cover with a 3¢ 1851 stamp and docketed 1852 is shown in Figure 4, it being sent only 3 months after the establishment of the P.O. and, of course, predating the stampless cover as well. -

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

THE WHARTON SCHOOL Contents

THE WHARTON SCHOOL CONTENTS DEAN’S MESSAGE 4 THOUGHTFUL LEADERS 6 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS POWERFUL IDEAS 16 FACULTY AND RESEARCH GLOBAL INFLUENCE 22 NETWORK AND CONNECTIONS ADVANCING BUSINESS. ADVANCING SOCIETY. As the birthplace of business education in 1881, Wharton is the most comprehensive source of business knowledge in the world. An international community of faculty, student and alumni leaders, we remain on the forefront of global business. 1 In 1881, American industrialist Joseph Wharton had Facts at A Glance a radical idea – to arm future generations with the knowledge and skills to unleash the transformative • Leading programs at every level of business power of business. education – from undergraduate, MBA, EMBA, This is the story of the Wharton School – the world’s and doctoral students, to senior executives first collegiate school of business – and our promise • 200+ courses and 25 research centers and to deliver continued, unparalleled knowledge and initiatives – more breadth and depth than at any leadership. No other single institution has other business school had as transformational an effect on the • 220+ faculty across 11 departments – one of the way business is conducted in the global market. largest, most published business school faculties Our foundational values continue to inspire our highest • 1,000+ organizations directly engaged with goal as an institution: to create the knowledge and Wharton – high-level businesses, non-profits, educate the leaders who will fuel the growth of and government agencies industries and -

Samuel Wetherill, Joseph Wharton, and the Founding of the ^American Zinc Industry

Samuel Wetherill, Joseph Wharton, and the Founding of the ^American Zinc Industry HE TWO people most closely associated with the founding of the zinc industry in the United States were the Philadel- Tphians Samuel Wetherill (i821-1890) and Joseph Wharton (1826-1909). From 1853 to about i860 they variously cooperated and competed with each other in setting up commercially successful plants for making zinc oxide and metallic zinc for the Pennsylvania and Lehigh Zinc Company at South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Both did their work in the face of an established and successful zinc industry in Europe. Accordingly, they looked to Europe for standards governing efficiency of production, quality of product, and the arts of management and marketing. They had to surpass at least some of these standards in order to establish the domestic industry on a firm basis. Zinc is a blue to grey metal found in deposits throughout the world. It is used for thousands of products, for example, in the fields of medicine, cosmetics, die casting alloys, galvanizing of iron, paint, rubber, ceramics, plastics, chemicals, and heavy metals. It ranks "only behind aluminum and copper in order of consumption among the nonferrous metals."1 In short, it has from an early stage in the Industrial Revolution been essential to the maintenance and progress of a technological society. The industry has two main branches. One is the manufacture of zinc oxide. The other is the making of metallic zinc or spelter, as it is called in the trade. These industries are relatively new in the western world. Portuguese and Dutch traders brought spelter to Europe from the Orient about the seventeenth century. -

Malleability and Metallography of Nickel

T281 MALLEABILITY AND METALLOGRAPHY OF NICKEL By P. D. Merica and R. G. Waltenberg ABSTRACT In the manufacture of " malleable " products of nickel and certain nickel alloys, such as forgings, rolled shapes, and castings, rather unusual metallur- gical treatments of the molten metal are resorted to in order that the cast product may be sufficiently malleable and ductile for the subsequent forging operations. The principal feature of these treatments is the addition to the molten metal before casting of manganese and magnesium. Ordinary furnace nickel without these additions will give a casting, in general, which is not malleable either hot or cold. It is demonstrated that such " untreated " nickel, or nickel alloys, are brit- tle because of the presence of small amounts of sulphur—as little as 0.005 per cent. This sulphur is combined with the nickel as Ni3 S2 , which collects in the form of thin and brittle films around the grains of nickel. This sulphide also melts (as an eutectic with nickel) at a very low temperature, about G30° C. Hence, at all temperatures the cohesion between the nickel grains is either completely destroyed or at least impaired by the presence of these films of sulphide, and the metal is brittle. Both manganese and magnesium react with molten NuS- to form sulphides of manganese or of magnesium. The latter, in particular, has a very high melt- ing point and. in addition, assumes a form of distribution in the metal mass which affects the malleability but slightly, viz, that of small equiaxed particles uniformly distributed throughout the metal grains. -

Horsehead/Marbella Other Name/Site Number

_______________________________________________ NPS Form lO. 8 No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name: Horsehead/Marbella other name/site number: 2. L.ocatlon street& number: 240 Highland Drive not for publication: N/A city/town: Jamestown vicinity: N/A state: RI county: Newport code: 005 zip code: 02835 3. ClassifIcation Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: Number of Resources within. Property: Contributing Noncontributing 2 buildings 1 sites 3 structures objects 6 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A ______________ ______________ ________________ ___________________________________ USbI/NPSNRHP Registration Form Page 2 Property name Horsehead/Marbella. Newbort County. Jamestown. RI 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination - request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _L. meets - does not meet the National Register Criteria. See conth,uation sheet. _2kg;N Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property - meets does not meet the National Register criteria. See continuation sheet. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 5. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register See continuation sheet. -

The Wharton-Fitler House

The Wharton-Fitler House A history of 407 Bank Avenue, Riverton, New Jersey Prepared by Roger T. Prichard for the Historical Society of Riverton, rev. November 30, 2019 © Historical Society of Riverton 407 Bank Avenue in 2019 photo by Roger Prichard This house is one of the ten riverbank villas which the founders of Riverton commissioned from architect Samuel Sloan, built during the spring and summer of 1851, the first year of Riverton’s existence. It looks quite different today than when built, due to an expansion in the 1880s. Two early owners, Rodman Wharton and Edwin Fitler, Jr., were from families of great influence in many parts of American life. Each had a relative who was a mayor of the City of Philadelphia. Page 1 of 76 The first owner of this villa was Philadelphian Rodman Wharton, the youngest of those town founders at age 31 and, tragically, the first to die. Rodman Wharton was the scion of several notable Philadelphia Quaker families with histories in America dating to the 1600s. Tragically, Rodman Wharton’s life here was brief. He died in this house at the age of 34 on July 20, 1854, a victim of the cholera epidemic which swept Philadelphia that summer. After his death, the house changed hands several times until it was purchased in 1882 by Edwin, Jr. and Nannie Fitler. Edwin was the son of Philadelphia’s popular mayor of the same name who managed the family’s successful rope and cordage works in Bridesburg. The Fitlers immediately enlarged and modernized the house, transforming its simpler 1851 Quaker appearance to a fashionable style today known as Queen Anne. -

19Th CENTURY ZINC MINING in the FRIEDENSVILLE, PA DISTRICT and the BIRTH of the U. S. ZINC INDUSTRY

19th CENTURY ZINC MINING IN THE FRIEDENSVILLE, PA DISTRICT AND THE BIRTH OF THE U. S. ZINC INDUSTRY L. Michael Kaas Society for Industrial Archaeology, June 2, 2018 ZINC MINES AND SMELTERS, 1850-1890 (Modified from Bleiwas and DiFrancesco, 2010) 1847 EXPLORATION MAP FRIEDENSVILLE, PA (Wittman, 1847; Smith, 1977) SAMUEL WETHERILL FAMILY LEAD WORKS, PHILA. CHEMIST, N J ZINC CO. SUPT. NEWARK ZINC WORKS PATENTS ZINC OXIDE FURNACE Samuel Wetherill as a Young Man (South Bethlehem Historical Society) 1853 WETHERILL AND GILBERT ZINC WORKS, SOUTH BETHLEHEM, PA PENNSYLVANIA AND LEHIGH ZINC COMPANY (PLZC) OPERATES THE FRIEDENSVILLE MINES, CONTRACTS WITH WETHERILL FOR OXIDE WETHERILL PROCESS: WETHERILL’S OXIDE FURNACE PATENT SAMUEL T. JONES’ BAG HOUSE PATENT FIRST* U.S. LARGE SCALE ZINC OXIDE PRODUCTION * New Jersey Zinc and Passaic Zinc were producing smaller amounts of oxide from Franklin-Sterling Hill Ores using other processes (Henry, 1860) 1854 PHILADELPHIA QUAKER INVESTORS TAKE OVER PLZC JOSEPH WHARTON SENT PROBLEMS WITH WETHERILL TO OVERSEE OPERATIONS DECLINING QUALITY OF OXIDE SALE OF OXIDE FOR OWN ACCOUNT USE OF COMPANY RESOURCES FOR EXPERIMENTS IN MAKING SPELTER (METALLIC ZINC) WHARTON’S ACTIONS IMPROVES MANAGEMENT INCREASES PROFITABILITY HIRES “COMPETENT MINER” TO RUN THE MINES (RICHARD W. PASCOE) Joseph Wharton, ca1850 (Wikipedia, 2013) WETHERILL SELLS OUT WHARTON CONSTRUCTS AND OPERATES FIRST COMMERCIAL METALLIC ZINC SMELTER IN THE U. S. (1860-1863) 1861-1865 CIVIL WAR, ZINC DEMAND AND PRICE INCREASES WHARTON BECOMES A WEALTHY MAN, LEAVES ZINC IN 1863 (1885 Sanborn Insurance Map) THE FRIEDENSVILLE MINES, 1853-1893 Pennsylvania and Lehigh Zinc Co. / Lehigh Zinc Co.* (1853-1876/1881) Uberroth Mine Old Hartman Mine Three Cornered Lot Mine New Hartman Mine Passaic Zinc Co. -

Kx Advisors Strengthens Leadership with Two Additions WASHINGTON DC (March 26, 2020) – Kx Advisors Announces Evelyn Tee and Brett Larson Have Joined the Firm

Kx Advisors Strengthens Leadership With Two Additions WASHINGTON DC (March 26, 2020) – Kx Advisors announces Evelyn Tee and Brett Larson have joined the firm. Evelyn Tee joins Kx Advisors as a Vice President in Washington, DC. Evelyn’s background in developing growth strategies for global biopharmaceutical clients is directly applicable in her new role at Kx Advisors. “Evelyn has proven expertise in a range of therapeutic areas, with a strong history of anticipating the needs of her clients” said Dan O’Neill, Senior Vice President. “We know Evelyn will not only cultivate new ideas to serve our clients in the years to come, but also further Kx Advisors' culture by mentoring future leaders.” Prior to Kx Advisors, Evelyn was a management consultant with the Boston Consulting Group and the Life Sciences Advisory Practice of EY. Evelyn earned an MBA in Operations and Marketing from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and is a Joseph Wharton Fellow. She also earned a BA in Mathematical Methods in Social Sciences (MMSS), Economics, and International Studies from Northwestern University. Brett Larson joins Kx Advisors as a Principal. He works with our pharma, biotech, and investor clients with a focus on business development, due diligence, forecasting, and corporate strategy. “We are fortunate to have someone of Brett’s caliber join us,” said Bob Serrano, Senior Vice President. “Brett’s extensive track record of identifying organic growth and M&A opportunities for leading biopharma clients makes him a strong addition to our firm.” Prior to Kx Advisors, Brett worked at SVB Leerink providing investment banking research coverage for emerging biotech companies. -

Wharton-PA-1

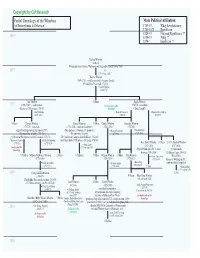

Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Whartons Main Political Affiliation: (of Pennsylvania & Delaware) 1763-83 Whig Revolutionary 1789-1823 Republican 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1600 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican ?? Richard Wharton (1646-83) (Emigrated from Overton, Westmoreland, England to Pennsylvania, 1683) 1650 = ???? (????-at least 1683) Thomas Wharton (1664-1718); (wealthy merchant); (became Quaker) (Philadelphia PA council, 1713-18) = Rachel Thomas (1664-1747) John Wharton 6 Others Joseph Wharton 1700 (1700-37/61?); (saddlemaker) See Carpenter of PA (1707-76); (merchant) (Chester co. PA coroner, 1730-37) Genealogy ("Duke Joseph") = Mary Dobbins Hannah Carpenter = = Hannah Owen (Ogden) (1696-1763) (1711-51) (1720-91) 4 Others Thomas Wharton Samuel Wharton 8 Others Charles Wharton Carpenter Wharton (1735-78); (merchant) (1732-1800); (merchant/landowner) (1742-1836) (1747-80) (signed Non-Importation Agreement, 1765) (PA legislature); (Vandalia Co. promoter) = Hannah Redwood = Elizabeth Davis (PA committee of safety, 1775-76) (PA committee of safety) (1759-96) (1751?-1816) (President PA supreme executive council, 1776-78) (US Continental Congress from Delaware, 1782-83) 1750Susannah Lloyd = = Elizabeth Fishbourne (Southwark district DE justice); (DE judge, 1790-91) (1739-72) (1752-1826) Gen. Robert Wharton 5 Others Lt. Col. Franklin Wharton = Sarah Lewis (1757-1834) (1767-1818) See Lloyd of PA (1732-at least 1762) Genealogy (Mayor Philadelphia PA 15 times (Commandante between 1798-1834) US Marine Corps, 1804-18) -

The Wharton School 1

The Wharton School 1 proposal to presentation through a project commensurate with THE WHARTON SCHOOL program duration. • Scholars programs (https://undergrad-inside.wharton.upenn.edu/ Founded in 1881 as the world’s first collegiate business school, the scholars-programs/)—Gain hands-on, in-depth experience from Wharton School (https://www.wharton.upenn.edu/) of the University proposal to presentation via a senior thesis and other activities. of Pennsylvania is shaping the future of business by incubating • Wharton PhD Submatriculation Program (http://doctoral- ideas, driving insights, and creating leaders who change the world. inside.wharton.upenn.edu/submatriculation/)—Submatriculate into a With a faculty of more than 235 renowned professors, Wharton PhD program in Accounting, Finance, Health Care Systems, Insurance has 5,000 undergraduate (https://undergrad.wharton.upenn.edu/), and Risk Management, Management, Marketing, Operations and MBA (https://mba.wharton.upenn.edu/), executive MBA (https:// Information Management, Business and Public Policy, or Statistics. executivemba.wharton.upenn.edu/), and doctoral (https:// doctoral.wharton.upenn.edu/) students. Each year 13,000 professionals For more information, visit: https://undergrad-inside.wharton.upenn.edu/ from around the world advance their careers through Wharton Executive research/. Education’s (https://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/) individual, company-customized, and online programs. More than 99,000 Wharton The University of Pennsylvania Wharton School is accredited by AACSB – alumni form a powerful global network of leaders who transform the International Association for Management Education. business every day. 1916: AACSB founded initially as the Association of Collegiate Schools For more information, visit www.wharton.upenn.edu (https:// of Business (ACSB); constitution is adopted June 17, 1916.