Resolving Conflicts of Duty in Fiduciary Relationships Arthur R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Asymmetry, Accountability and Fiduciary Loyalty

Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 37, No. 4 (2017), pp. 770–797 doi:10.1093/ojls/gqx003 Published Advance Access April 6, 2017 Lord Eldon Redux: Information Asymmetry, Accountability and Fiduciary Loyalty Amir N. Licht* Abstract—This article investigates the development of accountability and fiduciary loyalty as an institutional response to information asymmetries in agency relations, especially in firm-like settings. Lord Eldon articulated the crucial role of information asymmetries in opportunistic behaviour in the early 19th century, but its roots are much older. A 13th-century trend towards direct farming of English manors and the transformation of feudal accounting after the Domesday Book and early Exchequer period engendered profound developments. The manor emerged as (possibly the first) profit-maximising firm, complete with separation of ownership and control and a hierarchy of professional managers. This primordial firm relied on primordial fiduciary loyalty—an accountability regime backed by social norms that was tailored for addressing the acute information asymmetries in agency relations. Courts have gradually expanded this regime, which in due course enabled Equity to develop the modern duty of loyalty. These insights suggest implications for contemporary fiduciary loyalty. Keywords: fiduciary, loyalty, accountability, accounting, corporate governance, firm Introduction Judicial and scholarly discourse about fiduciaries’ duty of loyalty has emphasised the ‘no conflict’ and ‘no profit’ rules as a vehicle for coping with opportunistic behaviour much more than disclosure duties.1 This article seeks to rebalance this image of the structure of fiduciary loyalty by considering the roots of the fiduciary duty to account as an institutional response to acute * Professor of Law, Radzyner Law School, Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Israel. -

Fiduciary Law's “Holy Grail”

FIDUCIARY LAW’S “HOLY GRAIL”: RECONCILING THEORY AND PRACTICE IN FIDUCIARY JURISPRUDENCE LEONARD I. ROTMAN∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 922 I. FIDUCIARY LAW’S “HOLY GRAIL” ...................................................... 925 A. Contextualizing Fiduciary Law ................................................... 934 B. Defining Fiduciary Law .............................................................. 936 II. CERTAINTY AND FIDUCIARY OBLIGATION .......................................... 945 III. ESTABLISHING FIDUCIARY FUNCTIONALITY ....................................... 950 A. “Spirit and Intent”: Equity, Fiduciary Law, and Lifnim Mishurat Hadin ............................................................................ 952 B. The Function of Fiduciary Law: Sipping from the Fiduciary “Holy Grail” .............................................................. 954 C. Meinhard v. Salmon .................................................................... 961 D. Hodgkinson v. Simms ................................................................. 965 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 969 Fiduciary law has experienced tremendous growth over the past few decades. However, its indiscriminate and generally unexplained use, particularly to justify results-oriented decision making, has created a confused and problematic jurisprudence. Fiduciary law was never intended to apply to the garden -

Monitoring the Duty to Monitor

Corporate Governance WWW. NYLJ.COM MONDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 2011 Monitoring the Duty to Monitor statements. As a result, the stock prices of Chinese by an actual intent to do harm” or an “intentional BY LOUIS J. BEVILACQUA listed companies have collapsed. Do directors dereliction of duty, [and] a conscious disregard have a duty to monitor and react to trends that for one’s responsibilities.”9 Examples of conduct HE SIGNIFICANT LOSSES suffered by inves- raise obvious concerns that are industry “red amounting to bad faith include “where the fidu- tors during the recent financial crisis have flags,” but not specific to the individual company? ciary intentionally acts with a purpose other than again left many shareholders clamoring to T And if so, what is the appropriate penalty for the that of advancing the best interests of the corpo- find someone responsible. Where were the direc- board’s failure to act? “Sine poena nulla lex.” (“No ration, where the fiduciary acts with the intent tors who were supposed to be watching over the law without punishment.”).3 to violate applicable positive law, or where the company? What did they know? What should they fiduciary intentionally fails to act in the face of have known? Fiduciary Duties Generally a known duty to act, demonstrating a conscious Obviously, directors should not be liable for The duty to monitor arose out of the general disregard for his duties.”10 losses resulting from changes in general economic fiduciary duties of directors. Under Delaware law, Absent a conflict of interest, claims of breaches conditions, but what about the boards of mort- directors have fiduciary duties to the corporation of duty of care by a board are subject to the judicial gage companies and financial institutions that and its stockholders that include the duty of care review standard known as the “business judgment had a business model tied to market risk. -

Addressing Duty of Loyalty Parameters in Partnership Agreements: the More Is More Approach

Athens Journal of Law XY Addressing Duty of Loyalty Parameters in Partnership Agreements: The More is More Approach * By Thomas P. Corbin Jr. In drafting a partnership agreement, a clause addressing duty of loyalty issues is a necessity for modern partnerships operating under limited or general partnership laws. In fact, the entire point of forming a limited partnership is the recognition of the limited involvement of one of the partners or perhaps more appropriate, the extra-curricular enterprises of each of the partners. In modern operations, it is becoming more common for individuals to be involved in multiple business entities and as such, conflict of interests and breaches of the traditional and basic rules on duty of loyalty such as those owed by one partner to another can be nuanced and situational. This may include but not be limited to affiliated or self-interested transactions. State statutes and case law reaffirm the rule that the duty of loyalty from one partner to another cannot be negotiated completely away however, the point of this construct is to elaborate on best practices of attorneys in the drafting of general and limited partnership agreements. In those agreements a complete review of partners extra-partnership endeavours need to be reviewed and then clarified for the protection of all partners. Liabilities remain enforced but the parameters of what those liabilities are would lead to better constructed partnership agreements for the operation of the partnership and the welfare of the partners. This review and documentation by counsel drafting general and limited partnership agreements are now of paramount significance. -

The Nature of Fiduciary Liability in English Law

Coventry University Coventry University Repository for the Virtual Environment (CURVE) Author name: Panesar, S. Title: The nature of fiduciary liability in English law. Article & version: Published version Original citation & hyperlink: Panesar, S. (2007) The nature of fiduciary liability in English law. Coventry Law Journal, volume 12 (2): 1-19. http://wwwm.coventry.ac.uk/bes/law/about%20the%20school/Pages/LawJournal.as px Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Available in the CURVE Research Collection: March 2012 http://curve.coventry.ac.uk/open Page1 Coventry Law Journal 2007 The nature of fiduciary liability in English law Sukhninder Panesar Subject: Trusts. Other related subjects: Equity. Torts Keywords: Breach of fiduciary duty; Fiduciary duty; Fiduciary relationship; Strict liability Cases: Sinclair Investment Holdings SA v Versailles Trade Finance Ltd (In Administrative Receivership) [2005] EWCA Civ 722; [2006] 1 B.C.L.C. 60 (CA (Civ Div)) Attorney General v Blake [1998] Ch. 439 (CA (Civ Div)) *Cov. L.J. 2 Introduction Although the abuses of fiduciary relationship have long been one of the major concerns of equitable jurisdiction, the concept of a fiduciary has been far from clear. In Lac Minerals v International Corona Ltd1 La Forest J. -

Liberty in Loyalty: a Republican Theory of Fiduciary Law

CRIDDLE.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 4/4/2017 1:40 PM Liberty in Loyalty: A Republican Theory of Fiduciary Law Evan J. Criddle* Conventional wisdom holds that the fiduciary duty of loyalty is a prophylactic rule that serves to deter and redress harmful opportunism. This idea can be traced back to the dawn of modern fiduciary law in England and the United States, and it has inspired generations of legal scholars to attempt to explain and justify the duty of loyalty from an economic perspective. Nonetheless, this Article argues that the conventional account of fiduciary loyalty should be abandoned because it does not adequately explain or justify fiduciary law’s core features. The normative foundations of fiduciary loyalty come into sharper focus when viewed through the lens of republican legal theory. Consistent with the republican tradition, the fiduciary duty of loyalty serves primarily to ensure that a fiduciary’s entrusted power does not compromise liberty by exposing her principal and beneficiaries to domination. The republican theory has significant advantages over previous theories of fiduciary law because it better explains and justifies the law’s traditional features, including the uncompromising requirements of fiduciary loyalty and the customary remedies of rescission, constructive trust, and disgorgement. Significantly, the republican theory arrives at a moment when American fiduciary law stands at a crossroads. In recent years, some politicians, judges, and legal scholars have worked to dismantle two central pillars of fiduciary loyalty: the categorical prohibition against unauthorized conflicts of interest and conflicts of duty (the no-conflict rule), and the requirement that fiduciaries relinquish unauthorized profits (the no-profit rule). -

Fiduciary Duties

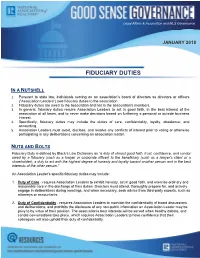

Legal Affairs & Association and MLS Governance JANUARY 2018 FIDUCIARY DUTIES IN A NUTSHELL 1. Pursuant to state law, individuals serving on an association’s board of directors as directors or officers (“Association Leaders”) owe fiduciary duties to the association. 2. Fiduciary duties are owed to the association and not to the association’s members. 3. In general, fiduciary duties require Association Leaders to act in good faith, in the best interest of the association at all times, and to never make decisions based on furthering a personal or outside business interest. 4. Specifically, fiduciary duties may include the duties of care, confidentiality, loyalty, obedience, and accounting. 5. Association Leaders must avoid, disclose, and resolve any conflicts of interest prior to voting or otherwise participating in any deliberations concerning an association matter. NUTS AND BOLTS Fiduciary Duty is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as “a duty of utmost good faith, trust, confidence, and candor owed by a fiduciary (such as a lawyer or corporate officer) to the beneficiary (such as a lawyer’s client or a shareholder); a duty to act with the highest degree of honesty and loyalty toward another person and in the best interests of the other person.” An Association Leader’s specific fiduciary duties may include: 1. Duty of Care - requires Association Leaders to exhibit honesty, act in good faith, and exercise ordinary and reasonable care in the discharge of their duties. Directors must attend, thoroughly prepare for, and actively engage in deliberations during meetings, and when necessary, seek advice from third-party experts, such as attorneys or accountants. -

The Duty of Loyalty in the Employment Relationship

Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues Volume 21, Issue 3, 2018 THE DUTY OF LOYALTY IN THE EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP: LEGAL ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EMPLOYERS AND WORKERS Frank J Cavico, Nova Southeastern University Bahaudin G Mujtaba, Nova Southeastern University Stephen Muffler, Nova Southeastern University ABSTRACT Capitalism, free markets and competition are all concepts and practices that are deemed to be good for the growth, development and sustainability of the economy while also benefiting consumers through more variety and lower prices. Of course, this assumption only holds true if markets and competition are open, honest and fair to all parties involved, including employers as every organization is entitled to faithful and fair service from its workers. The common law duty of loyalty in the employment relationship ensures fair competition and faithful service. Of course, a duty of loyalty is often violated when an employee begins to compete against his or her current employer. As such, the employee must not commit any illegal, disloyal, unethical or unfair acts toward his/her employer during the employment relationship. Accordingly, in this article, we provide a review of how the courts “draw the line” between permissible competition and disloyal actions. We discuss the key legal principles of the common law duty of loyalty, their implications for employees and employers and we provide practical recommendations for all parties in the employment relationship. Keywords: Duty of Loyalty, Faithless Servant, Fiduciary Relationships, Replevin, Common Law. INTRODUCTION This article examines the duty of loyalty in the employer-employee relationship. The focus is on the duty of the employee to act in a loyal manner while being employed by the employer. -

Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies

Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies James D. Johnson Jackson Kelly PLLC 221 N.W. Fifth Street P.O. Box 1507 Evansville, Indiana 47706-1507 812-422-9444 [email protected] James D. Johnson is a Member of Jackson Kelly PLLC resident in the Evansville, Indiana, office. He is Assistant Leader of the Commercial Law Practice Group and a member of the Construction Industry Group. For nearly three decades, Mr. Johnson has advised clients in a broad array of business matters, including complex commercial law, civil litigation and appellate law. He has been named to The Best Lawyers in America for Appellate Practice since 2007. Spencer W. Tanner of Jackson Kelly PLLC contributed to this manuscript. Modification of Fiduciary Duties in Limited Liability Companies Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................5 II. The Traditional Fiduciary Duties ..................................................................................................................5 III. Creation of Fiduciary Duties in Closely Held Business Organizations ......................................................6 A. General Partnerships ..............................................................................................................................6 B. Domestic Corporations ..........................................................................................................................6 -

Constraints on Pursuing Corporate Opportunities

Canada-United States Law Journal Volume 13 Issue Article 10 January 1988 Constraints on Pursuing Corporate Opportunities Stanley M. Beck Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj Part of the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Stanley M. Beck, Constraints on Pursuing Corporate Opportunities, 13 Can.-U.S. L.J. 143 (1988) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj/vol13/iss/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canada-United States Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Constraints on Pursuing Corporate Opportunities Stanley M. Beck* The question of corporate opportunity is one of the most difficult and, at the same time, one of the most interesting with respect to fiduciary duties. The Anglo-Canadian courts, and to an extent the American courts, have had a difficult time establishing any clear guidelines. The Canadian courts have taken a strict fiduciary approach. For example, the law of trusts for children has been applied in corporate opportunity cases, and such "simple" cases as Keech v. Sandford I (from 1726) and the later case of Parker v. McKenna2 (from 1874) have been repeatedly cited by courts considering this issue. The language of Lord Justice James in Parkerv. McKenna was that the court was not entitled to receive any evidence as to whether the prin- cipal did or did not suffer an injury, for the "safety of mankind requires that no agent shall be able to put his principal to the danger"3 of such an inquiry. -

The Chancellor's Conscience and Constructive Trusts

"CARDOZO'S FOOT": THE CHANCELLOR'S CONSCIENCE AND CONSTRUCTIVE TRUSTS H. JEFFERSON POWELL* I INTRODUCTION About 350 years ago, the English legal scholar John Selden articulated the classic common-lawyer's complaint about the chancery's exercise of jurisdiction in equity. Selden remarked in his Table Talk,1 Equity is A Roguish thing, for Law wee have a measure know what to trust too. Equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower soe is equity. Tis all one as if they should make the Standard for the measure wee call A foot, to be the Chancellors foot; what an uncertain measure would this be; One Chancellor has a long foot another A short foot a third an indifferent foot; tis the same thing in the Chancellors Conscience.2 The "Chancellor's foot" has since become proverbial shorthand for the argument that equity is an unjustified and unfortunate interference in the regular course of the rule of law.3 Selden's criticism went to the heart of equity's historic claim to legitimacy, the claim (originally made by Aristotle) that because law deals with general principles and is universally applicable, it necessarily will work injustice in some individual cases.4 The chancellor's jurisdiction, the argument went, is justified Copyright © 1993 by Law and Contemporary Problems * Professor of Law, Duke University. I wrote this article while a visitor at the University of North Carolina School of Law; I am deeply grateful for Dean Judith Wegner's personal and institutional support. Thanks also to Tom Shaffer and to the participants in the Modern Equity symposium for their comments and criticisms. -

Imagereal Capture

FIDUCIARIES : IDENTIFICATION AND REMEDIES D. S. K. ONG* In Hospital Products Ltd. v. United States Surgical Corporation and Others1 (hereinafter Hospital Products) Dawson J. said: Notwithstanding the existcnce of clear examples, no satisfactory, single test has emerged which will serve to identify a relationship which is fiduciary. In Consul Development Pty. Ltd. v. D.P.C. Estates Pty. Ltd.3 (herein- after Consul) Gibbs J. said :4 The question whather the remedy which the person to whom the duty is wed may obtain againsit the person who has violated the duty is proprietary or personal may sometimes be one of some difficulty. In some cases the fiduciary has been declared a trustee of the property which he has gained by his breach; in others he has been called upon to account folr his profits and sometimes the distinction batween the two remedies has not, it appears, been kept clearly in mind. Dawson J. in Hospital Products called attention to the difficulty in- herent in the ideneification of the fiduciary. Gibbs J. in Consul adverted to the difficulty of awarding an appropriate remedy for a breach of fiduciary duty. The identification of the fiduciary and the identifimtion of the approp- riate remedy against a fiduciary are matters of fundamental importance, yet these two fundamental matters are not untrammelled by uncertainty. This article is an attempit to mitigate that uncertainty. A. Identication of Fiduciaries. Hospital Products raises acutely the issue of who is a fiduciary. This particular issue in the case will be examined at the three levels of judi- cial decision: the 'trial,Qhe Colurt of Aplpal6 of New South Wales and the High Court.7 In this case, the defendants had agreed wii'rh the Plaintiff (a company incorporated in the United States of America) to become the latter's sole distributor in Australia of its surgical s~taples * Senior Lecturer in Law, School of Law, Macquarie University.