Death of a Posthuman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories. -

Hart Island Hart Island, Located One Mile East of City Island in the Bronx, Is Home to the Largest Municipal Cemetery in the United States

A Guide to Historic New York City Neighborhoods H A RT I SLAND BRONX HART ISLAND Hart Island, located one mile east of City Island in The Bronx, is home to the largest municipal cemetery in the United States. It was part of the property purchased by the English physician Thomas Pell from Native Americans in 1654. On May 16, 1868, the Department of Charities and Correction (later the Department of Correction or “DOC,” which split off from the Department of Public Charities in 1895), purchased The Historic Districts Council is New York’s citywide advocate for historic buildings Hart Island from the family of Edward Hunter to become a new municipal burial and neighborhoods. The Six to Celebrate program annually identifies six historic New facility called City Cemetery. Public burials began in April 1869. Since then, well over York City neighborhoods that merit preservation as priorities for HDC’s advocacy and a million people have been buried in communal graves with weekly interments still consultation over a yearlong period. managed by the DOC. The burials expanded across the entire island starting in 1985. Over its 150-year municipal history, it has also been home to a number of health and The six, chosen from applications submitted by community organizations, are selected penal institutions. The island is historically significant as a cultural site tied to a Civil on the basis of the architectural and historic merit of the area, the level of threat to the War-era burial system still in use today. neighborhood, the strength and willingness of the local advocates, and the potential for During the Civil War, in April 1864, the federal government leased Hart Island as a HDC’s preservation support to be meaningful. -

Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010

PL-P1 CT: Total Population by Census Tract Bronx, 2010 Total Population 319 8,000 or more 343 6,500 to 7,999 5,000 to 6,499 337 323 345 414 442 3,500 to 4,999 451.02 444 2,500 to 3,499 449.02 434 309 449.01 451.01 418 436 Less than 2,500 351 435 448 Van Cortlandt Park 428 420 430 H HUDSONPKWY 307.01 BROADWAY 422 426 335 408 424 456 406 285 394 484 295 I 87 MOSHOLU PKWY 404 458 283 297 396 281 301 431 392 287 279 398 460 BRONX RIVER PKWY 293.01 421 390 293.02 289 378 388 386 277 462.02 504 Pelham Bay Park 380 409 423 429.02 382 419 411 368 376 374 462.01 273 413 429.01 372 364 358 370 267.02 407.01 425 415 267.01 403.03 407.02 348 403.02 336 338 340 342 344 350 403.04 405.01 360 356 DEEGAN EXWY 261 265 405.02 269 263 401 399.01 332.02 W FORDHAM RD 397 316 312 302 E FORDHAM RD 330 328 324 326 318 314 237.02 310 257 253 399.02 255 237.03 334 332.01 239 HUTCHINSON RIVER PKWY 387 Botanical Gardens 249 383.01383.02 Bronx Park BX AND PELHAM PKWY 247 251 224.03 237.04 385 389 245.02 224.01 248 296 288 Hart Island 228 276 Cemetery 245.01 243 241235.01 391 224.04 53 393 250 300 235.02381 379 375.04 205.02 246 215.01 233.01 286 284 373 230 205.01 233.02 395 254 215.02 266.01 227.01 371 232 252 516 229.01 231 244 266.02 213.01 217 236 CROSS BRONX EXWY 365.01 227.02 369.01 363 256 229.02 238 213.02 209 227.03 165 200 BRUCKNER EXWY 201 369.02 365.02 361 274.01 240 264 367 220 210.01 204 211 223 225 171 167 359 219 163 274.02 221.01 169 Crotona Park 210.02 202 193 221.02 60 218 216.01 184 161 216.02 199 179.02 147.02 212 206.01 177.02 155 222 197 179.01 96 147.01 194 177.01 153 62 76 I 295 157 56 64 181.02 149 92 164 189 145 151 181.01175 72 160 195 123 54 70 166 183.01 68 78 162 125 40.01 183.02 121.01 135 50.02 48 GR CONCOURSE 173 143 185 44 BRUCKNER EXWY 152 131 127.01 121.02 52 CROSS BRONX EXWY DEEGAN EXWY 63 98 SHERIDAN EXWY 50.01 158 59.02 141 42 133 119 61 129.01 159 46 69 138 28 144 38 77 115.02 74 86 67 87 130 75 89 16 Sound View Park 110 I 295 65 71 20 24 90 79 85 84 132 118 73 BRUCKNER EXWY 43 83 51 2 37 41 35 31 117 4 39 23 93 33 25 27.02 27.01 19 1 Source: U.S. -

Connecticut Watersheds

Percent Impervious Surface Summaries for Watersheds CONNECTICUT WATERSHEDS Name Number Acres 1985 %IS 1990 %IS 1995 %IS 2002 %IS ABBEY BROOK 4204 4,927.62 2.32 2.64 2.76 3.02 ALLYN BROOK 4605 3,506.46 2.99 3.30 3.50 3.96 ANDRUS BROOK 6003 1,373.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.09 ANGUILLA BROOK 2101 7,891.33 3.13 3.50 3.78 4.29 ASH CREEK 7106 9,813.00 34.15 35.49 36.34 37.47 ASHAWAY RIVER 1003 3,283.88 3.89 4.17 4.41 4.96 ASPETUCK RIVER 7202 14,754.18 2.97 3.17 3.31 3.61 BALL POND BROOK 6402 4,850.50 3.98 4.67 4.87 5.10 BANTAM RIVER 6705 25,732.28 2.22 2.40 2.46 2.55 BARTLETT BROOK 3902 5,956.12 1.31 1.41 1.45 1.49 BASS BROOK 4401 6,659.35 19.10 20.97 21.72 22.77 BEACON HILL BROOK 6918 6,537.60 4.24 5.18 5.46 6.14 BEAVER BROOK 3802 5,008.24 1.13 1.22 1.24 1.27 BEAVER BROOK 3804 7,252.67 2.18 2.38 2.52 2.67 BEAVER BROOK 4803 5,343.77 0.88 0.93 0.94 0.95 BEAVER POND BROOK 6913 3,572.59 16.11 19.23 20.76 21.79 BELCHER BROOK 4601 5,305.22 6.74 8.05 8.39 9.36 BIGELOW BROOK 3203 18,734.99 1.40 1.46 1.51 1.54 BILLINGS BROOK 3605 3,790.12 1.33 1.48 1.51 1.56 BLACK HALL RIVER 4021 3,532.28 3.47 3.82 4.04 4.26 BLACKBERRY RIVER 6100 17,341.03 2.51 2.73 2.83 3.00 BLACKLEDGE RIVER 4707 16,680.11 2.82 3.02 3.16 3.34 BLACKWELL BROOK 3711 18,011.26 1.53 1.65 1.70 1.77 BLADENS RIVER 6919 6,874.43 4.70 5.57 5.79 6.32 BOG HOLLOW BROOK 6014 4,189.36 0.46 0.49 0.50 0.51 BOGGS POND BROOK 6602 4,184.91 7.22 7.78 8.41 8.89 BOOTH HILL BROOK 7104 3,257.81 8.54 9.36 10.02 10.55 BRANCH BROOK 6910 14,494.87 2.05 2.34 2.39 2.48 BRANFORD RIVER 5111 15,586.31 8.03 8.94 9.33 9.74 -

Parks Committee Meeting (Rev

Parks Committee Meeting (rev. 10/18/19) Thursday, October 10 @ 7:30 P.M. Present: T. Franklin, R. Bieder, P. Del-Debbio, C. Isales, D. Krynicki, J. Landi, S. McMillan, J. Russo, T. Smith Absent: I. Guanill Guests: S. Goodstein, T. McMahon, T. Kurtz, C.& R. Fitzpatrick, C. Fragola, C. Cebek, K. Zias, M. Anderson, J.Schwan, F. Rubin, Z. Hailu, E. Balkan, L. Baldwin, C. Swett, E. Joseph, M. Hunt, J. Doyle, L. Nye, L. & D. Malavolta Chairperson Franklin read the standing rules on committee meetings to the public. The meeting commenced at 7:30 P.M. with the Pledge of Allegiance. The first agenda item was a presentation led by Pelham Bay Parks Administrator, Marianne Anderson, on updates regarding the Pelham Bay Landfill. A digital copy of the presentation will be kept at the Board Office. The committee voted to have public speaking at the beginning of each committee meeting and at the discretion of the committee chairperson should the agenda contain multiple topics. The motion was proposed by T. Franklin and seconded by R. Bieder and unanimously approved. The last agenda item was a discussion on Hart Island. Community Board #10 voted to approve jurisdictional change of Hart Island in 2015. Currently, the Department of Corrections has jurisdiction. Recently proposed legislation will transfer Hart Island to the Department of Parks and Recreation. Residents of City Island submited petitions, statements, and other materials detailing their positions and opinions. Chairperson Franklin allowed Committee Members and members of the public to issue statements and/or question the subject of jurisdictional change. -

The Potter's Field

A Cemetery for the City of New York by: Rori Christian Espina Dajao Bachelor of Science inArchitecture University of Virginia, 1999 Submitted to the Department of Architecture inpartial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, February 2004. @2004 Rori Dajao, All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document inwhole or inpart. Signature of Author: Rori Dajko, Department of Architecture January 16, 2004 Certified by: J.leejin Yoon, Assisiant Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: William Hubbard, Jr. Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETS INsTIUVM OF TECHNOLOGY FEB 2 7 2004 LBAROTCH LIBRARIES thesis committee Thesis Supervisor: J. Meejin Yoon Assistant Professor of Architecture Thesis Readers: Arindam Dutta Assistant Professor of the History of Architecture Sheila Kennedy Principal, Kennedy and Violich Architecture Stephen Lacker Senior Associate, Kyu Sung Woo Architect, Inc. 02 A Cemetery for the City of New York Ror Christian Espina Dajao Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 16, 2004 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, February 2004. ABSTRACT Today, cemeteries are forgotten places. Once centers of cities and the societies they served, they have been pushed to the outskirts and turned into places of pure storage, devoid of memory. This thesis takes on the additional program of the Potter's Field: a burial place for the poor and unclaimed. Currently in New York the potter's field is located on Hart Island inthe Bronx. -

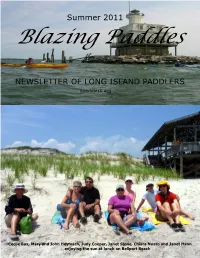

Lip Summer 2011

Summer 2011 NEWSLETTER OF LONG ISLAND PADDLERS lipaddlers.org Cecile Bax, Mary and John Heymach, Judy Cooper, Janet Stone, Chiara Nuzzo and Janet Hann Long Island Paddlers enjoying on trip tothe Middle sun at Ground lunch on Lighthouse Bellport Beach Sept 18, 2010 1 Letter from the President By Ken Fink Summer has finally arrived and it’s our high from The Theodore Roosevelt Sanctuary and season. Our trip leaders have already run some Audubon Center will discuss birds we may see pretty nice trips on both land and water, some of around our waters, and will make available water which you can read about in this issue of the resistant field guides for a nominal fee. On newsletter. But there’s a lot more to come. August 16th, club members Peter and Kathy Particularly important are the skills days Stoehr will share their experiences of their recent scheduled for 7/16 at Stony Brook Harbor and visit to the World Heritage sites of Galapagos 8/27 at Sunken Meadow State Park. Between the Islands and Machu Picchu. And on September 27 forks of Long Island you can visit Robins Island we have a special guest, Marcus Demuth, who on July 16th, Cutchogue Harbor and Little Peconic has world class status as an expedition kayaker. Bay on 7/23, Hallock Bay to Gardiner's Bay on Marcus was the first kayaker to circumnavigate 8/20, full moon paddles on Peconic and Flanders the Falkland Islands, a trip of over 680 miles in Bay on 8/9 and 9/11, day paddles on Flanders 22 days, (averaging almost 31 miles a day). -

Population Density by Census Tract Bronx, 2010

PL-P2 CT: Population Density by Census Tract Bronx, 2010 Persons Per Acre 319 200 and over 343 150 to 199.9 100 to 149.9 337 323 345 414 442 50 to 99.9 451.02 444 25 to 49.9 449.02 434 309 449.01 451.01 418 436 Under 25 351 435 448 Van Cortlandt Park 428 420 430 H HUDSONPKWY 307.01 BROADWAY 422 426 335 408 424 456 406 285 394 484 295 I 87 MOSHOLU PKWY 404 458 283 297 396 281 301 431 392 287 279 398 460 BRONX RIVER PKWY 293.01 421 390 293.02 289 378 388 386 277 462.02 504 Pelham Bay Park 380 409 423 429.02 382 419 411 368 376 374 462.01 273 413 429.01 372 364 358 370 267.02 407.01 425 415 267.01 403.03 407.02 348 403.02 336 338 340 342 344 350 403.04 405.01 360 356 DEEGAN EXWY 261 265 405.02 269 263 401 399.01 332.02 W FORDHAM RD 397 318 316 312 302 E FORDHAM RD 330 328 324 326 314 310 253 257 255 237.02399.02 237.03 334 332.01 239 HUTCHINSON RIVER PKWY 387 Botanical Gardens 249 383.01383.02 Bronx Park BX AND PELHAM PKWY 247 251 224.03 237.04 385 389 245.02 224.01 248 296 288 Hart Island 228 276 Cemetery 245.01 243 241235.01 391 224.04 53 393 250 300 235.02381 379 375.04 205.02 246 215.01 233.01 286 284 373 230 205.01 233.02 395 254 215.02 266.01 227.01 371 232 252 516 229.01 231 244 266.02 213.01 217 236 CROSS BRONX EXWY 365.01 227.02 369.01 363 256 229.02 238 213.02 209 227.03 165 200 BRUCKNER EXWY 201 369.02 365.02 361 274.01 240 264 367 220 210.01 204 211 223 225 171 167 359 219 163 274.02 221.01221.02 169 Crotona Park 210.02 202 193 60 218 216.01 184 179.02 216.02 199 147.02 161 206.01 177.02 155 212 222 197 179.01 96 147.01 194 153 62 76 I 295 177.01 157 64 181.02 149 56 92 164 189 181.01 145 151 175 72 160 195 123 54 70 166 183.01 68 78 162 125 40.01 183.02 121.01 135 50.02 48 GR CONCOURSE 173 143 185 44 BRUCKNER EXWY 152 131 127.01 121.02 52 CROSS BRONX EXWY DEEGAN EXWY 63 98 SHERIDAN EXWY 50.01 158 59.02 141 42 133 119 61 129.01 159 46 69 138 28 144 38 77 115.02 74 86 67 87 130 75 89 16 Sound View Park 110 I 295 65 71 20 24 90 79 85 84 132 118 73 BRUCKNER EXWY 43 83 51 2 37 41 35 31 117 4 39 23 93 33 25 27.02 27.01 19 1 Riker's Island Source: U.S. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 217 Water Street, Suite 300, New York, NY 10038 212-935-9831 waterfrontalliance.org CONTENTS The Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance works to protect, transform, and revitalize our harbor and waterfront. A Message from the Chairman and the President MWA PROGRAMS & EVENTS Legions take to the streets of Manhattan Our programs and events have a vast audi- • Open Waters Initiative to deliver a clarion call that our planet is ence. Harbor Camp has opened the eyes Community Eco Docks and DockNYC 4 changing at an alarming pace. Those of of more than 12,000 young people to the Ferry Transit Program 6 us who live, work, and play where the majesty and opportunity of the waterways. water meets the land see these changes City of Water Day festivities expand each • Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines 8 clearly, and are faced with the challenge summer, reaching more than 25,000 annu- of making our coastal city a place that ally, and the Waterfront Conference contin- can better manage the risk of the rising ues to grow in influence and attendance. • City of Water Day 10 tide and at the same time allow people to use and enjoy our magnificent harbor. Each of these efforts is incremental, but • Harbor Camp 12 collectively they are a revolution. And a We at the Metropolitan Waterfront revolution is what we need; indeed, we • Waterfront Conference 14 Alliance are committed to meeting this demand it! There is no quick, single solu- dual task of resilience and engagement tion to the complicated challenge of living with innovative programs. -

Hart Island Frequently Asked Questions - Page 1 of 3

City of New York Department of Correction HART ISLAND FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS - PAGE 1 OF 3 Q. What is the history of Hart Island? New York City purchased Hart Island in 1868 to serve as its Potter’s Field—a place of burial for unknown or indigent people. It is the tenth Potter’s Field in the City’s history. Previous NYC Potter’s Fields were located at the current sites of Washington Square, Bellevue Hospital, Madison Square, the NYC Public Library, Wards Island and Randall’s Island. Q. Are Potter’s Fields common throughout the United States? Yes. A number of jurisdictions set aside public burial sites or “potter’s fields” for individuals who cannot provide for their own burial, who have not been identified, or for those whose next of kin cannot be reached. Q. How many people are buried on Hart Island? Based on burial records, as many as one million people have been buried on Hart Island. Q. Who is in charge of Hart Island and overseeing burials? The Department of Correction is responsible for operating and maintaining NYC’s Potter’s Field. Our designation is set forth in the New York City Administrative Code. Q. Who determines whether someone will be buried on Hart Island? In New York City the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) takes custody of remains pending identification and claim by relatives. The OCME transfers unclaimed remains to the Department of Correction for burial on Hart Island. For additional information, please see the OCME website, www.nyc.gov/ocme. Q. -

Notice of Proposed Class Action Settlement and Fairness Hearing

Case 1:14-cv-09533-VSB Document 37 Filed 09/28/15 Page 16 of 16 NOTICE OF PROPOSED CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND FAIRNESS HEARING As a result of a proposed settlement agreement (“Agreement”) in a class action entitled Lusero v. The City of New York, family members and their invited guests (henceforth referred to as “Visitors”) can now visit the gravesites of individuals buried on Hart Island. For purposes of the Agreement, “family members” are defined as including parents, step-parents, children (biological or adopted), step-children, spouses, siblings, step-siblings, half-siblings, grandparents, grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, first cousins, second cousins, legal guardians of deceased individuals buried on Hart Island; wards of deceased guardians buried on Hart Island; and domestic partners of deceased individuals buried on Hart Island, who wish to visit the gravesites of said deceased individuals. The Agreement provides that The City will provide for two round-trips from the ferry dock on City Island in the Bronx to Hart Island on one weekend day per month (generally, alternating Saturdays and Sundays), year round. Each ferry trip will provide for a maximum of approximately 25 Visitors. While certain mementos will be permitted to be left at gravesites, under the terms of the Agreement, the City reserves, and is currently exercising, the right to prohibit all electronic devices on Hart Island. While the Agreement is already being implemented by the City, it has yet to be formally approved by the Court, which approval will make the Agreement fully binding upon the parties to the Agreement. If you are a “family member,” as defined above, and would like to schedule a visit to a gravesite on Hart Island, you may apply either (i) by calling DOC’s Hart Island visit line at 718-546-0911, or (ii) as of August 1, 2015, by visiting DOC’s on-line application portal for Hart Island, at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doc/html/contact/hart-island-grave-visit-request.shtml. -

Pocket Guide to New York

'^MM ? Ssisiociation 1906 A k Xhe Merchants Association of New York Pocket Guide to Ne^v York PRICE TEN CENTS Marck 1906 Ne%v York Life Bldg., Broadway and Leonard St. After Nov. 1st. 1906 Merchants' Association Bldg., 66-72 Lafayette St. LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Cooles Received WAY 10 1906 Copyright Entry , COPY B. Copyrighted, 1906, BY THE Merchants' Association OF New York. ^ PREFATORY. AST year more than, nine thousand out-of- town buyers registered at the offices of The Merchants' Association of New York. A great many of these asked information as to hotels, theatres, restaurants, ferries, railroad offices, street-car routes, elevated railroads, libraries, public buildings, pleasure resorts, short excursions, etc. The eleven hundred resident members of the Asso- ciation ask many questions as to the location of public offices, hack-rates, distances, automobile sta- tions and similar subjects. It has been found that a hand-book containing in- formation of the kind indicated, in a form convenient for ready-reference, will not only be a great con- venience for visiting merchants, but also in many respects for residents. This pocket-guide is pub- lished in response to that demand. It will be supplied without charge to visiting mer- chants registering at the offices of the Association; and a few free copies are at the disposal of each resident member. Members who desire a large quantity for distribu- tion to their customers will be supplied at about the cost price. CONTENTS. PAGE Ferries, Manhattan: I. Points Reached by Perries 1 II. Ferries from Manhattan and Desti- nation 2 Ferries, Brooklyn, Jersey City and Staten Island '.