Systems Engineering & Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

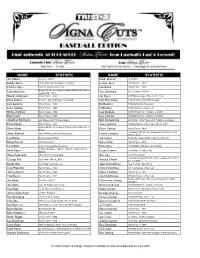

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Oakland Athletics Virtual Press

O AKLAND A THLETICS Post Game Notes Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum WayOakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900www.athletics.comA’s PR on Twitter @AsMedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (7-8) VS. TEXAS RANGERS (5-10) WEDNESDAY, APRIL 19, 2017 — OAKLAND COLISEUM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E Texas 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 Oakland 4 0 0 0 2 2 1 0 0 9 14 0 Win: Jesse Hahn (1-1) Loss: Martin Perez (1-2) OAKLAND NOTES TEXAS NOTES • The A’s snapped an 11-game streak in which they had committed • The Rangers’ bullpen allowed five runs...previous to today’s game, at least one error, their longest streak since a 15-game streak from Texas relievers had not allowed a run for two consecutive games 5/3/15-5/18/15. and had zero or one runs allowed in five of their last seven games. • Rajai Davis snapped a three-game (0-9) hitless streak with a double • Joey Gallo snapped his 11-at bat hitless streak with a solo home run in the first inning. in the fifth inning...marked his third of the season, first on the road. • The A’s went 4-for-6 (.667) to record three doubles and one single • In the third inning the Rangers challenged a play at first...the call for four runs in the first inning...Oakland had scored just one run in was overturned and the runner was ruled safe...time of the review the first innings of all prior contests this season and had a Major was 1:10. -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42 -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

![Topps Heritage SP[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8453/topps-heritage-sp-1-1568453.webp)

Topps Heritage SP[1]

Topps Heritage Short Prints and Inserts 2001 Topps Heritage Short Prints 8 ‐ Ramiro Mendoza (Black Back) 18 ‐ Roger Cedeno (Red Back) 19 ‐ Randy Velarde (Red Back) 28 ‐ Randy WolF (Black Back) 34 ‐ Javy Lopez (Black Back) 35 ‐ Aubrey HuFF (Black Back) 36 ‐ Wally Joyner (Black Back) 37 ‐ Magglio Ordonez (Black Back) 39 ‐ Mariano Rivera (Black Back) 40 ‐ Andy Ashby (Black Back) 41 ‐ Mark Buehrle (Black Back) 42 ‐ Esteban Loaiza (Red Back) 43 ‐ Mark Redman (Red Back) (2) 44 ‐ Mark Quinn (Red Back) 44 ‐ Mark Quinn (Black Back) 45 ‐ Tino Martinez (Red Back) 46 ‐ Joe Mays (Red Back) 47 ‐ Walt Weiss (Red Back) 50 ‐ Richard Hidalgo (Red Back) 51 ‐ Orlando Hernandez (Red Back) 53 ‐ Ben Grieve (Red Back) 54 ‐ Jimmy Haynes (Red Back) 55 ‐ Ken Caminiti (Red Back) 56 ‐ Tim Salmon (Red Back) 57 ‐ Andy Pettitte (Red Back) 59 ‐ Marquis Grissom (Red Back) 62 ‐ Miguel Tejada (Red Back) 66 ‐ CliFF Floyd (Red Back) 72 ‐ Andruw Jones (Red Back) 403 ‐ Mike Bordick SP Classic Renditions CR1 ‐ Mark McGwire CR5 ‐ Chipper Jones CR6 ‐ Pat Burrell CR8 ‐ Manny Ramirez 2002 Topps Heritage Short Prints 53 ‐ Alex Rodriguez SP 244 ‐ Barry Bonds SP 368 ‐ RaFael Palmeiro SP 370 ‐ Jason Giambi SP 373 ‐ Todd Helton SP 374 ‐ Juan Gonzalez SP 377 ‐ Tony Gwynn SP 383 ‐ Ramon Ortiz SP 384 ‐ John Rocker SP 394 ‐ Terrence Long SP 395 ‐ Travis Lee SP 396 ‐ Earl Snyder SP Classic Renditions CR‐2 ‐ Brian Giles CR‐3 ‐ Roger Cedeno CR‐8 ‐ Jimmy Rollins (2) CR‐10 ‐ Shawn Green (2) 2003 Topps Heritage Short Prints / Variations 156 ‐ Randall Simon (Old Logo SP) 170 ‐ Andy Marte SP 375 ‐ Ken GriFFey Jr. -

BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 the Game I’Ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams As Told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer Recalls Opening Day Walk-Off Homer

CONTENTS January/February 2016 — Volume 75. No. 1 FEATURES 9 Warmup Tosses by Bob Kuenster Royals Personified Spirit of Winning in 2015 12 2015 All-Star Rookie Team by Mike Berardino MLB’s top first-year players by position 16 Jake Arrieta: Pitcher of the Year by Patrick Mooney Cubs starter raised his performance level with Cy Young season 20 Bryce Harper: Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan MVP year is only the beginning for young star 24 Kris Bryant: Rookie of the Year by Bruce Levine Cubs third baseman displayed impressive all-around talent in debut season 30 Mark Melancon: Reliever of the Year by Tom Singer Pirates closer often made it look easy finishing games 34 Prince Fielder: Comeback Player of the Year by T.R. Sullivan Slugger had productive season after serious injury 38 Farewell To Yogi Berra by Marty Appel Yankee legend was more than a Hall of Fame catcher MANNY MACHADO Orioles young third 44 Strikeouts on the Rise by Thom Henninger baseman is among the game’s elite stars, page 52. Despite many changes to the game over the decades, one constant is that strikeouts continue to climb COMING IN BASEBALL DIGEST: 48 The Game I’ll Never Forget 2016 Preview Issue by Billy Williams as told to Barry Rozner Hall of Famer recalls Opening Day walk-off homer 52 Another Step To Stardom by Tom Worgo Manny Machado continues to excel 59 Baseball Profile by Rick Sorci Center fielder Adam Jones DEPARTMENTS 4 Baseball Stat Corner 6 The Fans Speak Out 28 Baseball Quick Quiz SportPics Cover Photo Credits by Rich Marazzi Kris Bryant and Carlos Correa 56 Baseball Rules Corner by SportPics 58 Baseball Crossword Puzzle by Larry Humber 60 7th Inning Stretch January/February 2016 3 BASEBALL STAT CORNER 2015 MLB AWARD WINNERS CARLOS CORREA SportPics (Top Five Vote-Getters) ROOKIE OF THE YEAR AWARD AMERICAN LEAGUE Player, Team Pos. -

Batting Order

Fantistics Projected MLB Lineups ( updated 7/30/06 ) Roto-accurate projections by LYLE (the AX cuts deep) LOGAN National League National East Atlanta Florida NY Mets Philadelphia Washington 1 Marcus Giles 2B 1 Am'z'ga//H R'mirez cf/ss 1 Jose Reyes SS 1 Jimmy Rollins SS 1 Alfonso Soriano LF 2 Edgar Renteria SS 2 H Ramirez//Uggla ss/2b 2 Paul Lo Duca C 2 Chase Utley 2B 2 Felipe Lopez SS 3 McCann//Frncoeur c/rf 3 Miguel Cabrera 3B 3 Carlos Beltran CF 3 Bobby Abreu RF 3 Ryan Zimmerman 3B 4 Andruw Jones CF 4 Jacobs//C Ross 1b/cf 4 Carlos Delgado 1B 4 Pat Burrell LF 4 Nick Johnson 1B 5 LaRoche//M Diaz 1b/lf 5 Uggla//Wllngham 2b/lf 5 David Wright 3B 5 Ryan Howard 1B 5 Austin Kearns RF 6 Frncoeur//McCann rf/c 6 Hermida//Helms rf/1b 6 Cliff Floyd LF 6 Aaron Rowand CF 6 Marlon Anderson 2B 7 Willy Aybar 3B 7 Wllnghm//H'rmida lf/rf 7 Jo Valentin//Nady 2b/rf 7 Abraham Nunez 3B 7 Church//Matos CF 8 Lngrhns//L'Roche lf/1b 8 Miguel Olivo C 8 Nady//Jo Valentin rf/2b 8 Mike Lieberthal C 8 Schneider//Fick C 9 PITCHER 9 PITCHER 9 PITCHER 9 PITCHER 9 PITCHER bench & DL bench & DL bench & DL bench & DL bench & DL Chipper Jones reg 3B Joe Borchard of Chris Woodward inf David Dellucci of Jose Vidro reg 2B Scott Thorman of/1b Reg. Abercrombie of Endy Chavez of Shane Victorino of Damian Jackson util Pete Orr util Matt Treanor c Eli Marrero util Danny Sandoval inf Alex Escobar of Todd Pratt c Ramon Castro c Chris Coste c Daryle Ward of/1b National Central Chi Cubs Cincinnati Houston Milwaukee Pittsburgh St Louis 1 Juan Pierre CF 1 Ryan Freel RF 1 Craig Biggio 2B -

Front Office

FRONT OFFICE The A’s added Jason Giambi (left) and Matt Holliday (right) to bolster their offense for the 2009 season. COOPERSTOWN AWAITS ‘BASEBALL’S GREATEST LEADOFF HITTER’ FRONT OFFICE HENDERSON TO BECOME 15TH ATHLETIC INDUCTED INTO HALL OF FAME JULY 26 The greatest leadoff hitter in baseball history has a date with Cooperstown this year. On Sunday, July 26, Rickey Henderson—the pride of Oakland, Calif. and his hometown team, the Oakland Athletics—will stride to the podium in upstate New York and join the game’s immortals. And while fans and media are sure to join in the discussion, there should be no debate: Rickey was, indeed, the greatest leadoff man the sport has ever known. Better than Cobb. Better than Rose. Better than Brock. Better 2009 ATHLETICS than Wills. Henderson, who was born in the shadow of the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum and graduated from Oakland Tech High School, played 25 Major League seasons, including four stints with the A’s that spanned 14 years (1979-84, 1989-93, 1994-95, 1998). And during that quarter century of baseball, the mercurial outfielder posted unprecedented offensive numbers. He set Major League career records for runs scored (2,295), stolen bases (1,406) and walks (2,190, later eclipsed by Barry Bonds), and banged out 3,055 hits, 297 home runs and 1,115 RBI, with a .401 on-base percentage. He REVIEW also hit 81 home runs leading off a game, still a Major League mark. Some of his most shining moments came in an Oakland uniform. In 1982, he shattered the single-season record by stealing 130 bases. -

2009 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

2009 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Alex Rodriguez 2 Omar Vizquel 3 Andy Marte 4 Chipper Jones, Albert Pujols, Matt Holliday LL 5 John Lackey 6 Raul Ibanez 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Terry Francona MG 9 Dallas McPherson 10 Dan Uggla 11 Fernando Tatis 12 Andrew Carpenter RC 13 Ryan Langerhans 14 Jon Rauch 15 Nate McLouth 16 Evan Longoria HL 17 Bobby Cox MG 18 George Sherrill 19 Edgar Gonzalez 20 Brad Lidge 21 Jack Wilson 22 Evan Longoria, David Price CC 23 Gerald Laird 24 Frank Thomas 25 Jon Lester 26 Jason Giambi 27 Jon Niese RC 28 Mike Lowell 29 Jerry Hairston 30 Ken Griffey Jr. 31 Ian Stewart 32 Daric Barton 33 Jose Guillen 34 Brandon Inge 35 David Price RC 36 Kevin Slowey 37 Erick Aybar 38 Eric Wedge MG 39 Stephen Drew 40 Carl Crawford 41 Mike Mussina 42 Jeff Francoeur Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Joe Mauer, Dustin Pedroia, Milton Bradley LL 44 Geoff Jenkins 45 Aubrey Huff 46 Brad Ziegler 47 Jose Valverde 48 Mike Napoli 49 Kazuo Matsui 50 David Ortiz 51 Will Venable RC 52 Marco Scutaro 53 Jonathan Sanchez 54 Dusty Baker MG 55 J.J. Hardy 56 Edwin Encarnacion 57 Jo-Jo Reyes 58 Travis Snider RC 59 Eric Gagne 60 Mariano Rivera 61 Lance Berkman, Carlos Lee CC 62 Brian Barton 63 Josh Outman RC 64 Miguel Montero 65 Mike Pelfrey 66 Dustin Pedroia 67 Andruw Jones 68 Kyle Lohse 69 Rich Aurilia 70 Jermaine Dye 71 Mat Gamel RC 72 David Dellucci 73 Shane Victorino 74 Trey Hillman MG 75 Rich Harden 76 Marcus Thames 77 Jed Lowrie 78 Tim Lincecum 79 David Eckstein 80 Brian McCann 81 Ryan Howard, Adam Dunn, Carlos Delgado LL 82 Miguel -

Weekly Notes 083117

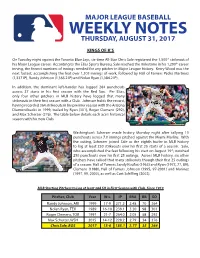

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES THURSDAY, AUGUST 31, 2017 KINGS OF K’S On Tuesday night against the Toronto Blue Jays, six-time All-Star Chris Sale registered the 1,500th strikeout of his Major League career. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, Sale reached the milestone in his 1,290th career inning, the fewest numbers of innings needed for any pitcher in Major League history. Kerry Wood was the next fastest, accomplishing the feat over 1,303 innings of work, followed by Hall of Famers Pedro Martinez (1,337 IP), Randy Johnson (1,365.2 IP) and Nolan Ryan (1,384.2 IP). In addition, the dominant left-hander has logged 264 punchouts across 27 starts in his fi rst season with the Red Sox. Per Elias, only four other pitchers in MLB history have logged that many strikeouts in their fi rst season with a Club. Johnson holds the record, having recorded 364 strikeouts in his premier season with the Arizona Diamondbacks in 1999, trailed by Ryan (301), Roger Clemens (292), and Max Scherzer (276). The table below details each ace’s historical season with his new Club. Washington’s Scherzer made history Monday night after tallying 10 punchouts across 7.0 innings pitched against the Miami Marlins. With the outing, Scherzer joined Sale as the eighth hurler in MLB history to log at least 230 strikeouts over his fi rst 25 starts of a season. Sale, who accomplished the feat following his start on August 19th, notched 250 punchouts over his fi rst 25 outings. Across MLB history, six other pitchers have tallied that many strikeouts though their fi rst 25 outings of a season: Hall of Famers Sandy Koufax (1965) and Ryan (1973, 77, 89); Clemens (1988), Hall of Famers Johnson (1995, 97-2001) and Marinez (1997, 99, 2000), as well as Curt Schilling (2002). -

Seton Hall Sports Poll Finds Mlb Has Perception Problems on Both Drugs and Race

SETON HALL SPORTS POLL FINDS MLB HAS PERCEPTION PROBLEMS ON BOTH DRUGS AND RACE However, Its Athletes Score Best Among Team Sports in Image One in Four Thought Tiger’s Masters Return Helped His Image; Rating As World’s Top Athlete Drops Dramatically S. Orange, NJ, April 22, 2010 – Major League Baseball has problems with public perception in both the areas of drugs and racism, according to a poll conducted this week by the Seton Hall Sports Poll. Sixty-three percent of respondents felt that MLB has not rid itself of abusers of performance enhancing drugs, with only 20% believing that it had. In addition, 78% agreed that teams have not signed certain available free agents because they are African-American. This was suggested last week by Minnesota infielder Orlando Hudson. "We both know what it is," Hudson told reporter Jeff Passan of Yahoo! Sports, speaking of the failures of Jermaine Dye and Gary Sheffield to land contracts. "You'll figure it out. I'm not gonna say it because then I'll be in (trouble)." The poll was conducted earlier this week among 855 randomly called adults 18 and over throughout the United States, with a margin of error due to sampling of 3% for most estimates. Other factors also may affect the total error. “At the same time that MLB honors the legacy of Jackie Robinson with all players wearing number 42 for a day, this is a troubling perception for them,” noted Rick Gentile, director of the Seton Hall Sports Poll, conducted by The Sharkey Institute. “Likewise, despite efforts to rid the sport of drugs, there remains an overwhelming feeling that PEDs are still very much in use.” Baseball did fare well however in the public perception of it’s sport, with 55% of its Major League athletes producing a positive impression on the public, as compared to 49% of football players 44% of basketball players and 39% of hockey players.