Rossini's Reform: the Controversy Surrounding the Use of Embellishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Alberto Zedda

Le pubblicazioni del Rossini Opera Festival sono realizzate con il contributo di Amici del Friends of the Note al programma Rossini Opera Festival Rossini Opera Festival della XL Edizione Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica XL edizione 11~23 agosto 2019 L’edizione 2019 è dedicata a Montserrat Caballé e a Bruno Cagli MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI Regione Marche Enti fondatori Il Rossini Opera Festival si avvale della collaborazione scientifica della Fondazione Rossini Il Festival 2019 si attua con il contributo di Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali Comune di Pesaro Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino Comune di Pesaro Regione Marche in collaborazione con Intesa Sanpaolo Fondazione Gruppo Credito Valtellinese Fondazione Scavolini con l’apporto di Abanet Internet Provider Bartorelli-Rivenditore autorizzato Rolex Eden Viaggi Grand Hotel Vittoria - Savoy Hotel - Alexander Museum Palace Hotel Harnold’s Hotel Excelsior Ratti Boutique Subito in auto Teamsystem Websolute partecipano AMAT-Associazione marchigiana attività teatrali AMI-Azienda per la mobilità integrata e trasporti ASPES Spa Azienda Ospedaliera San Salvatore Centro IAT-Informazione e accoglienza turistica Conservatorio di musica G. Rossini Si ringrazia UBI Banca per il contributo erogato tramite Art Bonus United Nations Designated Educational, Scientific and UNESCO Creative City Cultural Organization in 2017 Il Festival è membro di Italiafestival e di Opera Europa Sovrintendente Ernesto Palacio Direttore generale Olivier Descotes Presidente Relazioni -

Document (Pdf)

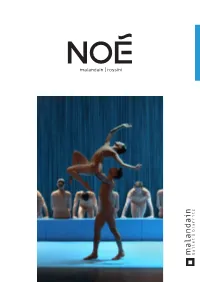

Creation / Basque Eurocity Teatro Victoria Eugenia - Donostia / San Sebastián NOAH Choreography Thierry Malandain Music Gioacchino Rossini - Messa di Gloria Set and costumes Jorge Gallardo Lighting design Francis Mannaert Dressmaker Véronique Murat Set production Frédéric Vadé Coproducers Chaillot - Théâtre National de la Danse(Paris), Opéra de Saint-Etienne, Donostia Kultura - Teatro Victoria Eugenia de Donostia / San Sebastián - Ballet T, CCN Malandain Ballet Biarritz. Partners Opéra de Reims, Théâtre de Gascogne - le Pôle, Theater Bonn (Allemagne), Forum am Schlosspark – Ludwigsburg (Allemagne) CREATION / BASQUE EUROCITY Teatro Victoria Eugenia de Donostia / San Sebastián, january 14th and 15th 2017 CREATION / FRENCH PREMIERE Chaillot - Théâtre National de la Danse (Paris) beetween May 10th and 24th 2017 Ballet for 22 dancers Lenght 70 minutes © Olivier Houeix Mickaël Conte et Irma Hoffren © Olivier Houeix NOAH CREATION 2017 Inspired by the parable of Noah’s Ark, Thierry Malandain’s new ballet once again addresses themes that he holds dear, such as Mankind and its future, destiny, fate, and the environment. From this story, which incidentally is rarely used in dance, he retains the symbolism rather than the religious message. Just as in the Biarritz choreographer’s previous work, Noah is punctuated with discreet references. For example, water, alternately destructive and life-sustaining, which is represented here as the element that gives new life to Mankind. Similarly, it represents the sacrament that we’re supposed to walk away from feeling different, if not changed. Mankind which boarded the Ark for forty days will emerge transformed. In essence, every artist dreams that the audience leaves a performance slightly changed. Malandain presents a more abstract Noah, who is not only a Christian reference to a new Adam, but also a figure common to various civilizations that lived through a flood and were saved by a protective, providential man. -

Kisd Band Ms 3 Curriculum Year at a Glance

KISD BAND MS 3 CURRICULUM YEAR AT A GLANCE TEXT: Essential Elements for Band THE LEARNER WILL: 1st 9-Weeks 2nd 9-Weeks 3rd 9-Weeks 4th 9-Weeks Identify, define, write, and analyze whole, half, quarter, paired and single Identify, define, write, and analyze all previously learned elements adding eighth, sixteenth, dotted half, and dotted quarter notes with corresponding 9/8, 12/8, and 5/4 time signatures and the keys of G and Db. (1B, 1D, 1C, rests in simple time and dotted quarters and triplets in compound time; 2B, 3F) multi-measure rests; repeat, first and second endings, da capo al fine, dal segno al fine, da capo al coda, dal segno al coda; dynamics (pp-ff); staccato, Identify, define, write and analyze all previously learned elements in addition to the following: largo-presto, sforzando, fortepiano, chord structures legato, accent, marcato; crescendo, decrescendo; 2/4, 3/4 ,4/4, 2/2, 6/8; keys and tuning in a major key. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) of Bb, Eb, F; instrument names; musical forms; fermata; andante, moderato, ritardando, accelerando, largo, adagio, allegro. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) Perform a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, fingerings, and Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, accurate intonation. (1B) fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 80bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing a triplet note pattern). -

Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865)

1/3 Data Livret de Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865) Langue : Italien Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres musicales Date : 1813 Note : "Dramma serio" en 2 actes créé à Milan, Teatro alla Scala, le 26 décembre 1813. - Livret de Felice Romani d'après "Zenobia di Palmira" d'Anfossi Éditions de Aureliano in Palmira (19 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Partitions (13) Cavatina del maestro , Gioachino Rossini Quartetto pastorale , Gioachino Rossini Rossini nell' Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini nell'Aureliano in Palmira. (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Composto dal maestro , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et accompagnement de piano] Aureliano in Palmira, opéra , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini in due atti, musica di (1792-1868), Paris : Palmira, musica del (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini [Partition chant et Schonenberger , [s.d.] maestro Rossini. [Chant et , [s.d.] piano] piano] Terzettino nel Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Aureliano in Palmira. Mille sospiri e lagrimé. - [7] Aureliano in Palmira , Felice Romani (2019) (1788-1865), Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Pesaro : Fondazione Rossini data.bnf.fr 2/3 Data Aureliano in Palmira, opera , Felice Romani Mille sospiri e Lagrime. Air , Gioachino Rossini in 2 atti (1788-1865), Gioachino à 2 v. tiré d'Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : [s.n.] , (1855) Rossini (1792-1868), Paris Palmira 1823 : Schonenberger , [1855] (1823) Ecco mi, ingiustinumi. -

![[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2533/stendhal-joachim-rossini-von-maria-ottinguer-leipzig-1852-472533.webp)

[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852

REVUE DES DEUX MONDES , 15th May 1854, pp. 731-757. Vie de Rossini , par M. BEYLE [STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852. SECONDE PÉRIODE ITALIENNE. — D’OTELLO A SEMIRAMIDE. IV. — CENERENTOLA ET CENDRILLON. — UN PAMPHLET DE WEBER. — LA GAZZA LADRA. — MOSÈ [MOSÈ IN EGITTO]. On sait que Rossini avait exigé cinq cents ducats pour prix de la partition d’Otello (1). Quel ne fut point l’étonnement du maestro lorsque le lendemain de la première représentation de son ouvrage il reçut du secrétaire de Barbaja [Barbaia] une lettre qui l’avisait qu’on venait de mettre à sa disposition le double de cette somme! Rossini courut aussitôt chez la Colbrand [Colbran], qui, pour première preuve de son amour, lui demanda ce jour-là de quitter Naples à l’instant même. — Barbaja [Barbaia] nous observe, ajouta-t-elle, et commence à s’apercevoir que vous m’êtes moins indifférent que je ne voudrais le lui faire croire ; les mauvaises langues chuchotent : il est donc grand temps de détourner les soupçons et de nous séparer. Rossini prit la chose en philosophe, et se rappelant à cette occasion que le directeur du théâtre Valle le tourmentait pour avoir un opéra, il partit pour Rome, où d’ailleurs il ne fit cette fois qu’une rapide apparition. Composer la Cenerentola fut pour lui l’affaire de dix-huit jours, et le public romain, qui d’abord avait montré de l’hésitation à l’endroit de la musique du Barbier [Il Barbiere di Siviglia ], goûta sans réserve, dès la première épreuve, cet opéra, d’une gaieté plus vivante, plus // 732 // ronde, plus communicative, mais aussi trop dépourvue de cet idéal que Cimarosa mêle à ses plus franches bouffonneries. -

Gioachino Rossini the Journey to Rheims Ottavio Dantone

_____________________________________________________________ GIOACHINO ROSSINI THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS OTTAVIO DANTONE TEATRO ALLA SCALA www.musicom.it THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS ________________________________________________________________________________ LISTENING GUIDE Philip Gossett We know practically nothing about the events that led to the composition of Il viaggio a Reims, the first and only Italian opera Rossini wrote for Paris. It was a celebratory work, first performed on 19 June 1825, honoring the coronation of Charles X, who had been crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Rheims on 29 May 1825. After the King returned to Paris, his coronation was celebrated in many Parisian theaters, among them the Théâtre Italien. The event offered Rossini a splendid occasion to present himself to the Paris that mattered, especially the political establishment. He had served as the director of the Théatre Italien from November 1824, but thus far he had only reproduced operas originally written for Italian stages, often with new music composed for Paris. For the coronation opera, however, it proved important that the Théâtre Italien had been annexed by the Académie Royale de Musique already in 1818. Rossini therefore had at his disposition the finest instrumentalists in Paris. He took advantage of this opportunity and wrote his opera with those musicians in mind. He also drew on the entire company of the Théâtre Italien, so that he could produce an opera with a large number of remarkable solo parts (ten major roles and another eight minor ones). Plans for multitudinous celebrations for the coronation of Charles X were established by the municipal council of Paris in a decree of 7 February 1825. -

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868)

4 CDs 4 Christian Benda Christian Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Sinfonia Prague COMPLETE OVERTURES COMPLETE ROSSINI GIOACHINO COMPLETE OVERTURES ROSSINI GIOACHINO 4 CDs 4 GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792–1868) COMPLETE OVERTURES Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Christian Benda Rossini’s musical wit and zest for comic characterisation have enriched the operatic repertoire immeasurably, and his overtures distil these qualities into works of colourful orchestration, bravura and charm. From his most popular, such as La scala di seta (The Silken Ladder) and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie), to the rarity Matilde of Shabran, the full force of Rossini’s dramatic power is revealed in these masterpieces of invention. Each of the four discs in this set has received outstanding international acclaim, with Volume 2 described as “an unalloyed winner” by ClassicsToday, and the Prague Sinfonia Orchestra’s playing described as “stunning” by American Record Guide (Volume 3). COMPLETE OVERTURES • 1 (8.570933) La gazza ladra • Semiramide • Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra (Il barbiere di Siviglia) • Otello • Le siège de Corinthe • Sinfonia in D ‘al Conventello’ • Ermione COMPLETE OVERTURES • 2 (8.570934) Guillaume Tell • Eduardo e Cristina • L’inganno felice • La scala di seta • Demetrio e Polibio • Il Signor Bruschino • Sinfonia di Bologna • Sigismondo COMPLETE OVERTURES • 3 (8.570935) Maometto II (1822 Venice version) • L’Italiana in Algeri • La Cenerentola • Grand’overtura ‘obbligata a contrabbasso’ • Matilde di Shabran, ossia Bellezza, e cuor di ferro • La cambiale di matrimonio • Tancredi CD 4 COMPLETE OVERTURES • 4 (8.572735) Il barbiere di Siviglia • Il Turco in Italia • Sinfonia in E flat major • Ricciardo e Zoraide • Torvaldo e Dorliska • Armida • Le Comte Ory • Bianca e Falliero 8.504048 Booklet Notes in English • Made in Germany ℗ 2013, 2014, 2015 © 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

|What to Expect from L'elisir D'amore

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM L’ELISIR D’AMORE AN ANCIENT LEGEND, A POTION OF QUESTIONABLE ORIGIN, AND THE WORK: a single tear: sometimes that’s all you need to live happily ever after. When L’ELISIR D’AMORE Gaetano Donizetti and Felice Romani—among the most famous Italian An opera in two acts, sung in Italian composers and librettists of their day, respectively—joined forces in 1832 Music by Gaetano Donizetti to adapt a French comic opera for the Italian stage, the result was nothing Libretto by Felice Romani short of magical. An effervescent mixture of tender young love, unforget- Based on the opera Le Philtre table characters, and some of the most delightful music ever written, L’Eli s ir (The Potion) by Eugène Scribe and d’Amore (The Elixir of Love) quickly became the most popular opera in Italy. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber Donizetti’s comic masterpiece arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in 1904, First performed May 12, 1832, at the and many of the world’s most famous musicians have since brought the opera Teatro alla Cannobiana, Milan, Italy to life on the Met’s stage. Today, Bartlett Sher’s vibrant production conjures the rustic Italian countryside within the opulence of the opera house, while PRODUCTION Catherine Zuber’s colorful costumes add a dash of zesty wit. Toss in a feisty Domingo Hindoyan, Conductor female lead, an earnest and lovesick young man, a military braggart, and an Bartlett Sher, Production ebullient charlatan, and the result is a delectable concoction of plot twists, Michael Yeargan, Set Designer sparkling humor, and exhilarating music that will make you laugh, cheer, Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer and maybe even fall in love.